Logs, for Cabin Preservation Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bi-Metal Hole Saws Designed with Time Savings and Longevity in Mind

FLEXIBLE. EASY-TO-USE. DURABLE. BI-METAL HOLE SAWS DESIGNED WITH TIME SAVINGS AND LONGEVITY IN MIND. THE UNIVERSAL PRODUCT FOR CUTTING HOLES IN WOOD AND METAL. BI-METAL HOLE SAWS When it comes to purchasing a Bi-Metal Hole Saw, look no further. The IDEAL® Bi-Metal Hole Saw utilizes M42 high-speed steel with 8% premium cobalt and a rigged solid back plate. Providing 2.3x more holes than leading manufactures with the highest strength and greater wear resistance. The extreme deep gulleted teeth design clears out uniform chips that minimize binding on the job that provides 1.2x faster drilling time than the leading manufacturers in the market. With a standard 1-7/8” cutting dept, you can save time cutting 2’x4’s with a single pass design. The IDEAL® Bi-Metal Hole Saws effectively cut through a wide range of materials, including stainless steel, sheet metal, as well as common non-fer- rous materials, such as aluminum, copper, brass, wood, engineered wood, nail embedded wood and plastics. When it comes to IDEAL vs. the competition, we have the professional in mind. The wide offering includes sizes from 7/8” to 6” that include diamond side eyes to provide ease of slug removal. The 2” to 6” Bi-Metal Hole Saws have large cat eyes on the back, that not only provide line of sight but aid in plug removal. IDEAL is the professional’s choice for Bi-Metal Hole Saws. Average NumberAverage # of Holes before failure of Holes Drilled AVERAGE DRILL TIME(STATISTICALLY LOWER LIMIT)Average Drill Time 80 2.3X 180 1.2X MORE HOLES THAN FASTER THAN THE 70 160 THE COMPETITION 140 COMPETITION 60 LIGHT BLUE 120 50 100 DARK BLUE 40 80 ORANGE 30 60 GREEN 20 DRILL TIME(SECONDS) AVERAGE # OF HOLES 40 RED 10 20 MAROON 0 0 LIGHT BLUE ORANGE GREEN RED MAROON LIGHT BLUE DARK BLUE ORANGE GREEN RED MAROON Orange Green IDEAL Dk. -

A Guide to Maintaining the Historic Character of Your Forest Service Recreation Residence

United States Forest Department of Service Agriculture Technology & Development Program A Guide to Maintaining 2300–Recreation April 2014 the Historic Character 1423–2815P–MTDC of Your Forest Service Recreation Residence Cover: This photo in September 1923 shows a newly built recreation residence in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains at the Silver Creek tract of the Rainier National Forest, which is now part of the Mt. Baker- Snoqualmie National Forest in the Pacific Northwest Region. A Guide to Maintaining the Historic Character of Your Forest Service Recreation Residence Kathleen Snodgrass Project Leader USDA Forest Service Technology and Development Center Missoula, MT April 2014 USDA Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, Adjudication, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410, by fax (202) employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, 690-7442 or email at [email protected]. disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual’s income is Persons with Disabilities derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment Individuals who are deaf, hard of hearing or have speech disabilities and you wish to file either or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases an EEO or program complaint please contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) 877-8339 or (800) 845-6136 (in Spanish). -

Other Top Reasons to Visit Hakone

MAY 2016 Japan’s number one English language magazine Other Top Reasons to Visit Hakone ALSO: M83 Interview, Sake Beauty Secrets, Faces of Tokyo’s LGBT Community, Hiromi Miyake Lifts for Gold, Best New Restaurants 2 | MAY 2016 | TOKYO WEEKENDER 7 17 29 32 MAY 2016 guide radar 26 THE FLOWER GUY CULTURE ROUNDUP THIS MONTH’S HEAD TURNERS Nicolai Bergmann on his upcoming shows and the impact of his famed flower boxes 7 AREA GUIDE: EBISU 41 THE ART WORLD Must-see exhibitions including Ryan McGin- Already know the neighborhood? We’ve 28 JUNK ROCK ley’s nudes and Ville Andersson’s “silent” art thrown in a few new spots to explore We chat to M83 frontman Anthony Gon- zalez ahead of his Tokyo performance this 10 STYLE WISH LIST 43 MOVIES month Three films from Japanese distributor Gaga Spring fashion for in-between weather, star- that you don’t want to miss ring Miu Miu pumps and Gucci loafers 29 BEING LGBT IN JAPAN To celebrate Tokyo Rainbow Pride, we 12 TRENDS 44 AGENDA invited popular personalities to share their Escape with electro, join Tokyo’s wildest mat- Good news for global foodies: prepare to experiences suri, and be inspired at Design Festa Vol. 43 enjoy Greek, German, and British cuisine 32 BEAUTY 46 PEOPLE, PARTIES, PLACES The secrets of sake for beautiful skin, and Dewi and her dogs hit Yoyogi and Leo in-depth Andaz Tokyo’s brand-new spa menu COFFEE-BREAK READS DiCaprio comes to town 17 HAKONE TRAVEL SPECIAL 34 GIRL POWER 50 BACK IN THE DAY Our nine-page guide offers tips on what to Could Hiromi Miyake be Japan’s next This month in 1981: “Young Texan Becomes do, where to stay, and how to get around gold-winning weightlifter? Sumodom’s 1st Caucasian Tryout” TOKYO WEEKENDER | MAY 2016 | 3 THIS MONTH IN THE WEEKENDER Easier navigation Keep an eye out for MAY 2016 a new set of sections that let you, the MAY 2016 reader, have a clear set of what’s going where. -

Fischer Chisel

CATALOG OCTOBER 2021 DRILL BITS AND BITS CATALOG DRILL BITS AND BITS CHISELS FLAT CHISEL SDS MAX High-performance flat chisel for SDS Max drill chuck. * Long life span thanks to the specially hardened steel. * Excellent working comfort because of the high oscillation endurance. * Secure transfer of force due to the SDS Max seat. * Fischer chisel ... CODE 504284 504286 504287 PRICE € 13,61 € 15,43 € 19,96 FLAT CHISEL SDS PLUS High-performance flat chisel for SDS Plus drill chuck. * Excellent working comfort because of the high oscillation endurance. * Long life span thanks to the specially hardened steel. * Secure transfer of force due to the SDS Plus seat. * Fischer chis ... CODE 504278 PRICE € 13,83 HOLLOW CHISEL SDS PLUS High-performance gouge for SDS Plus drill chuck. * Excellent working comfort because of the high oscillation endurance. * Long life span thanks to the specially hardened steel. * Secure transfer of force due to the SDS Plus seat. * Fischer chisel SDS ... CODE 504280 PRICE € 28,43 POINTED CHISEL SDS MAX High-performance pointed chisel for SDS Max drill chuck. * Excellent working comfort because of the high oscillation endurance. * Long life span thanks to the specially hardened steel. * Secure transfer of force due to the SDS Max seat. * Fischer chi ... CODE 504281 504282 504283 PRICE € 13,61 € 15,43 € 19,96 CATALOG DRILL BITS AND BITS CHISELS POINTED CHISEL SDS PLUS High-performance pointed chisel for SDS Plus drill chuck. * Excellent working comfort because of the high oscillation endurance. * Long life span thanks to the specially hardened steel. * Secure transfer of force due to the SDS Plus seat. -

Folk Log Structures in Pennsylvania

Folk Log Structures in Pennsylvania By Thomas M. Brandon Research Assistants: Jonathan P. Brandon and Mario Perona FOLK ARCHITECTURE The term ‘folk architecture’ is often used to draw a distinction between popular or landmark architecture and is nearly synonymous with the terms ‘vernacular architecture’ and ‘traditional architecture.’ Therefore, folk architecture includes those dwellings, places of worship, barns, and other structures that are designed and built without the assistance of formally schooled and professionally trained architects. Folk architecture differs from popular architecture in several ways. For example, folk architecture tends to be utilitarian and conservative, reflecting the specific needs, economics, customs, and beliefs of a particular community. (Source: Oklahoma History Society’s Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, Website. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/F/FO002.html, Alyson L. Greiner, February, 17, 2011). Note. Much of the data and pictures found in this field guide came from a study on log structures in 18 counties of western and central Pennsylvania. The Historic Value of Folk Log Structures The study of folk log construction, also known as horizontal log construction, is exciting because, unlike most artifacts from the pioneer era, log structures have not been moved from where the pioneers used them. The log structure remains intact within the landscape the pioneer who built it intended. Besides the structure itself, which provides valuable information about the specific people who occupied it, the surrounding historic landscape tells it own story of how the family lived, from location of water sources and family dump to the layout of fields, location with other houses in the neighborhood and artifacts found in the ground still in context with their original use. -

2017 CRAFTS Auction Results

CRAFTS of NJ Auction April 8, 2017 Lot High Bid # (US$) Description 1 80.00 Unusual Large Signed Axe 2 20.00 Lot of 3 Stanley Block Planes 3 50.00 Boxlot of Tools: Stanley, 2 Drawknives, Box Scraper, etc. 4 30.00 Lot of 2 Planes: Large Jointer, Rounding 5 20.00 Lot of 2 Bench Planes, 1 by M. Nash 6 45.00 Small Tool Chest Filled w/ Tools 7 12.00 Lot of 2 Eric Sloane Books: ABC Book, Spirits of '76 8 10.00 Stanley No. 6 Fore Plane & A Sargent Plane 9 30.00 Currier's Fleshing Knife by A. Proctor, Exeter NH, ex-Courser Collection 10 20.00 Lot: 2 Crosscut Saws, 2 6' Bar Clamps, Peavey 11 50.00 Stanley No. 20 Square, SW (18") 12 45.00 Lot of 5 Large Augers 13 27.00 Lot: Wooden Rake, Eel Gig, Apple Picker 14 20.00 Lot: 2 Disston Saws, Miniature Anvil 15 50.00 Lot: 2 Hollow Augers in Old Pasteboard Box, 2 Stanley No. 88 Clapboard Siding Marker 16 15.00 Lot of 4 Tool Collector Books 17 25.00 Lot of 2 Large Leather Punches 18 40.00 Stanley No. 18 Plane 19 40.00 Lot: Brass Ship Bevel, Mahogany Bevel, Box Architect's Scales 20 30.00 Lot of 2 Adzes: Shipbuilder's, Curved 21 25.00 Boxlot of Misc. Tools: Hammers, Plumb Bobs, etc. 22 35.00 Lot of 3 Saws: 2 Buck, 1 Frame 23 45.00 Lot of 10 Molding Planes 24 55.00 Lot of Stanley Planes: No. -

Printable Intro (PDF)

round wood timber framing make an A shape. They can still be found in old barns and cottages. But they had to find very long pieces of wood, so people started making small squares and building them up to the right shape, then joining the squares diagonally to make a roof. By now, everyone was squaring their timber, because a) it's more uniform, and removes uncertaintly; b) all joints can be almost identical – you don't have to take into consideration the shape of the tree; unskilled people can then be employed to make standard joints; and c) right- angles fit better, joints become stronger, and you can fit bricks / wattle & daub in more easily. Everything is flat and flush. what are the benefits? So round wood could be considered old- fashioned, but the reasons for resurrecting it are aesthetic and ecological. It looks pretty; it's a Hammering a peg into a round wood joint with a natural antidote to the square, flat, generic world home-made wooden mallet. that we build; it reconnects people with the forms of the natural world that are more relaxing to the eye; and it reminds us that wood comes from what is it? trees. Also, you can use coppiced wood and Round wood is straight from the tree (with or smaller dimension timber. If you use squared without bark), without any processing, squaring or wood, you need to cut down mature trees and re- planking. Timber framing is creating the structural plant, but a coppiced tree continually re-grows. framework for a building from wood. -

Chapter 12 Review

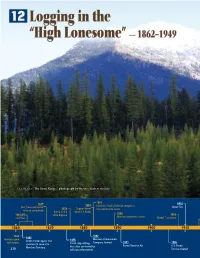

FIGURE 12.1: “The Swan Range,” photograph by Donnie Sexton, no date 1883 1910 1869 1883 First transcontinental Northern Pacifi c Railroad completes Great Fire 1876 Copper boom transcontinental route railroad completed begins in Butte Battle of the 1889 1861–65 Little Bighorn 1908 Civil War Montana becomes a state Model T invented 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1862 1882 1862 Montana gold Montana Improvement Anton Holter opens fi rst 1875 rush begins Salish stop setting Company formed 1891 1905 commercial sawmill in Forest Reserve Act U.S. Forest Montana Territory fi res after confrontation 230 with law enforcement Service created READ TO FIND OUT: n How American Indians traditionally used fire n Who controlled Montana’s timber industry n What it was like to work as a lumberjack n When and why fire policy changed The Big Picture For thousands of years people have used forests to fill many different needs. Montana’s forestlands support our economy, our communities, our homes, and our lives. Forests have always been important to life in Montana. Have you ever sat under a tall pine tree, looked up at its branches sweeping the sky, and wondered what was happen- ing when that tree first sprouted? Some trees in Montana are 300 or 400 years old—the oldest living creatures in the state. They rooted before horses came to the Plains. Think of all that has happened within their life spans. Trees and forests are a big part of life in Montana. They support our economy, employ our people, build our homes, protect our rivers, provide habitat for wildlife, influence poli- tics, and give us beautiful places to play and be quiet. -

Final Environmental Impact Statement Sublette County, Wyoming

United States Department of Agriculture Final Environmental Forest Service Impact Statement November 2005 Cottonwood II Vegetation Management Project Big Piney Ranger District, Bridger-Teton National Forest, Wyoming The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Cottonwood II Vegetation Management Project Final Environmental Impact Statement Sublette County, Wyoming Lead Agency: USDA Forest Service Cooperating Agencies: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Responsible Official: Gregory Clark District Ranger Bridger-Teton National Forest P.O. Box 218 Big Piney, WY 83113 For Information Contact: Jeff Laub P.O. Box 218 Big Piney, WY 83113 307.276.3375 Abstract: This Final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) was prepared to evaluate and disclose the environmental impacts of alternative vegetation management strategies to manage vegetation resources in the North and South Cottonwood Creeks drainages on the Big Piney Ranger District, Bridger-Teton National Forest (B-TNF). The Big Piney Ranger District is proposing to implement vegetation management in the North and South Cottonwood Creeks drainages over the next 5 to 10 years. -

Trail Maintenance Manual 8Th Edition New York – New Jersey Trail Conference

Connecting People with Nature Since 1920 Trail Maintenance Manual 8th Edition New York – New Jersey Trail Conference May 2020 www.nynjtc.org/tmm CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 TRAIL MAINTENANCE ASSIGNMENTS 3 TRAIL MAINTAINER RESPONSIBILITIES 4 TRAIL MAINTENANCE ANNUAL CYCLE 5 SAFETY 6 INSPECTION 7 HOW OFTEN AND WHEN 7 SPECIAL SITUATIONS 7 REPORTING 8 IMPORTANCE OF REPORTING 8 REGULAR REPORTING 8 PROBLEM REPORTING 8 CLEARING 9 EQUIPMENT LIST 9 STANDARDS AND METHODS 11 TRAIL CLEANUP 11 BLAZING 15 STANDARDS FOR ALL BLAZING 15 BLAZING GUIDELINES 15 HINTS FOR BLAZING TRIPS 16 TAG BLAZING 17 PAINT BLAZING 17 SPECIAL TRAIL MARKINGS 19 PROTECTING THE TRAIL AND ITS STRUCTURES 20 TREADWAY REHABILITATION 20 INCOMPATIBLE USES 23 EDUCATING TRAIL USERS 25 INJURY AND INSURANCE PROTOCOL 26 ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING 28 WEB ACCESS AND YOUR DASHBOARD 29 VOLUNTEER SERVICE AGREEMENTS 30 CHECKLIST OF WHAT A MAINTAINER SHOULD KNOW 31 Page 2 INTRODUCTION The New York-New Jersey Trail Conference was formed in 1920 “to coordinate the efforts of walking organizations in the States of New York and New Jersey, and to build and maintain trails and shelters in these states.” The Trail Conference is dedicated to keeping each trail in its charge easily passable, clearly and consistently marked, in a safe condition, and harmonious with its surroundings. As a trail maintainer, you have volunteered to assist the Trail Conference in its most important mission. We thank you for your very valuable service. The purpose of this manual is to define the role of a trail maintainer and serve as a reference document to supplement formal classroom instruction and on-the- job training. -

62 Low Angle Jack Plane.Indd

Low Angle Jack Plane Low Angle Jack Plane P. O. Box 9, Route 1 Warren, Maine 04864 1-800-327-2520 [email protected] wwww.lie-nielsen.comww.lie-nielsen.com PProp.rop. 6655 WWarning:arning: Bronze and brass alloys contain lead, Makers of a chemical known to the State of California to cause cancer and birth defects or other reproductive harm. Heirloom Quality Tools® Wash hands after handling. Low Angle Jack Plane Low Angle Jack Plane P. O. Box 9, Route 1 Warren, Maine 04864 1-800-327-2520 [email protected] wwww.lie-nielsen.comww.lie-nielsen.com PProp.rop. 6655 WWarning:arning: Bronze and brass alloys contain lead, a chemical known to the State of California to cause Makers of cancer and birth defects or other reproductive harm. Heirloom Quality Tools® Wash hands after handling. Low Angle Jack Plane Lateral Adjustment: The Low Angle Jack Plane intentionally has very little lateral adjustment of the blade. This is an advantage. As you adjust The Lie-Nielsen Low Angle Jack Plane is based on the Stanley No. 62, the blade, it will track squarely with the sole. The disadvantage is that one of the three large format low angle block planes that Stanley made. you must sharpen the blade square. Today there are many good jigs on At 14" long, the No. 62 was the largest. It was produced between 1905 the market that make this easy to do. If you fi nd that you don’t like this and 1942*. It is often referred to as a butcher’s block plane, giving you feature, you can grind the blade narrower to give more lateral play. -

A Big Success

VALUE ADDED The Little Things Make This Company a Big Success by Bill Tice or Rob Wrightman, president and CEO of True North Log Homes Inc. in Bracebridge, Ont., making the decision to go into the highly competitive log home business was easy. Developing a product that would set him apart from the competition was supposed to have been the hard part. But for Wrightman, achieving that com- petitive edge simply meant going back to basics and solving a long-term problem for the log home industry – gaps that are created when the structure settles and allows air into the home. age log building you will have about 40 rods,” he explains. Wrightman, who has a self-proclaimed interest in tech- “In the past, it would take two days to install all of the rods nology, has four U.S. and Canadian patents in the works with two guys. Now, with the spring action, it takes half a right now, including one for his new “Log Lock Thru-bolt” day or less with one man.” assembly system, which is a spring loaded, self-adjusting Following more than two years of development, Wright- method of joining the logs together. “Two feet from every man started installing the new “Log Lock” system in his corner and between each door and window opening we fac- company’s log homes earlier this year, but there is more to tory drill a hole for a one–piece through bolt to be inserted his log homes than just steel rods, springs and bolts. “It’s also at the time of assembly,” explains Wrightman when provid- the quality of the materials we use, the workmanship, and ing a simplistic description of the technology.