Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Custom to Code. a Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football

From Custom to Code From Custom to Code A Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football Dominik Döllinger Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Humanistiska teatern, Engelska parken, Uppsala, Tuesday, 7 September 2021 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Associate Professor Patrick McGovern (London School of Economics). Abstract Döllinger, D. 2021. From Custom to Code. A Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football. 167 pp. Uppsala: Department of Sociology, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-2879-1. The present study is a sociological interpretation of the emergence of modern football between 1733 and 1864. It focuses on the decades leading up to the foundation of the Football Association in 1863 and observes how folk football gradually develops into a new form which expresses itself in written codes, clubs and associations. In order to uncover this transformation, I have collected and analyzed local and national newspaper reports about football playing which had been published between 1733 and 1864. I find that folk football customs, despite their great local variety, deserve a more thorough sociological interpretation, as they were highly emotional acts of collective self-affirmation and protest. At the same time, the data shows that folk and early association football were indeed distinct insofar as the latter explicitly opposed the evocation of passions, antagonistic tensions and collective effervescence which had been at the heart of the folk version. Keywords: historical sociology, football, custom, culture, community Dominik Döllinger, Department of Sociology, Box 624, Uppsala University, SE-75126 Uppsala, Sweden. -

Glasgow's Tobacco Lords: an Examination of Wealth Creators in the Eighteenth Century

Peters, Carolyn Marie (1990) Glasgow's tobacco lords: an examination of wealth creators in the eighteenth century. PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4540/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] GLASGOW'S TOBACCO LORDS: AN EXAMINATION OF WEALTH CREATORS IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY CAROLYN MARIE PETERS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D DEPARTMENT OF SCOTTISH HISTORY SEPTEMBER 1990 @CAROLYN MARIE PETERS 1990 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the process of writing this thesis, I have benefitted from the help and information of many people. I would like to thank the staff of the Mitchell Library and the Strathclyde Regional Archives in Glasgow, the staff of the Scottish Record Office in Edinburgh, and the staff of the Glasgow University Library and the Glasgow University Archives. In particular I would like to thank, first and foremost, my supervisor Dr. John McCaffrey who saw me through these three years, Professor Ian B. Cowan who always encouraged me, Professor Thomas Devine for his helpful suggestions, and my friends and family whose support was invaluable. -

Scottsih Newspapers Have a Long Hisotry Fof Involvement With

68th IFLA Council and General Conference August 18-24, 2002 Code Number: 051-127-E Division Number: V Professional Group: Newspapers RT Joint Meeting with: - Meeting Number: 127 Simultaneous Interpretation: - Scottish Newspapers and Scottish National Identity in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries I.G.C. Hutchison University of Stirling Stirling, UK Abstract: Scotland is distinctive within the United Kingdom newspaper industry both because more people read papers and also because Scots overwhelmingly prefer to read home-produced organs. The London ‘national’ press titles have never managed to penetrate and dominate in Scotland to the preponderant extent that they have achieved in provincial England and Wales. This is true both of the market for daily and for Sunday papers. There is also a flourishing Scottish local weekly sector, with proportionately more titles than in England and a very healthy circulation total. Some of the reasons for this difference may be ascribed to the higher levels of education obtaining in Scotland. But the more influential factor is that Scotland has retained distinctive institutions, despite being part of Great Britain for almost exactly three hundred years. The state church, the education system and the law have not been assimilated to any significant amount with their counterparts south of the border. In the nineteenth century in particular, religious disputes in Scotland generated a huge amount of interest. Sport in Scotlaand, too, is emphatically not the same as in England, whether in terms of organisation or in relative popularity. Additionally, the menu of major political issues in Scotland often has been and is quite divergent from England – for instance, the land question and self-government. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

Post-Office Annual Directory

frt). i pee Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/postofficeannual182829edin n s^ 'v-y ^ ^ 9\ V i •.*>.' '^^ ii nun " ly Till [ lililiiilllliUli imnw r" J ifSixCtitx i\ii llatronase o( SIR DAVID WEDDERBURN, Bart. POSTMASTER-GENERAL FOR SCOTLAND. THE POST OFFICE ANNUAL DIRECTORY FOR 18^8-29; CONTAINING AN ALPHABETICAL LIST OF THE NOBILITY, GENTRY, MERCHANTS, AND OTHERS, WITH AN APPENDIX, AND A STREET DIRECTORY. TWENTY -THIRD PUBLICATION. EDINBURGH : ^.7- PRINTED FOR THE LETTER-CARRIERS OF THE GENERAL POST OFFICE. 1828. BALLAN'fVNK & CO. PRINTKBS. ALPHABETICAL LIST Mvtt% 0quaxt&> Pates, kt. IN EDINBURGH, WITH UEFERENCES TO THEIR SITUATION. Abbey-Hill, north of Holy- Baker's close, 58 Cowgate rood Palace BaUantine's close, 7 Grassmrt. Abercromby place, foot of Bangholm, Queensferry road Duke street Bangholm-bower, nearTrinity Adam square. South Bridge Bank street, Lawnmarket Adam street, Pleasance Bank street, north, Mound pi. Adam st. west, Roxburgh pi. to Bank street Advocate's close, 357 High st. Baron Grant's close, 13 Ne- Aird's close, 139 Grassmarket ther bow Ainslie place, Great Stuart st. Barringer's close, 91 High st. Aitcheson's close, 52 West port Bathgate's close, 94 Cowgate Albany street, foot of Duke st. Bathfield, Newhaven road Albynplace, w.end of Queen st Baxter's close, 469 Lawnmar- Alison's close, 34 Cowgate ket Alison's square. Potter row Baxter's pi. head of Leith walk Allan street, Stockbridge Beaumont place, head of Plea- Allan's close, 269 High street sance and Market street Bedford street, top of Dean st. -

The Atlas of Digitised Newspapers and Metadata: Reports from Oceanic Exchanges

THE ATLAS OF DIGITISED NEWSPAPERS AND METADATA: REPORTS FROM OCEANIC EXCHANGES M. H. Beals and Emily Bell with additional contributions by Ryan Cordell, Paul Fyfe, Isabel Galina Russell, Tessa Hauswedell, Clemens Neudecker, Julianne Nyhan, Mila Oiva, Sebastian Padó, Miriam Peña Pimentel, Lara Rose, Hannu Salmi, Melissa Terras, and Lorella Viola and special thanks to Seth Cayley (Gale), Steven Claeyssens (KB), Huibert Crijns (KB), Nicola Frean (NLNZ), Julia Hickie (NLA), Jussi-Pekka Hakkarainen (NLF), Chris Houghton (Gale), Melanie Lovell-Smith (NLNZ), Minna Kaukonen (NLF), Luke McKernan (BL), Chris McPartlanda (NLA), Maaike Napolitano (KB), Tim Sherratt (University of Canberra) and Emerson Vandy (NLNZ) Document: DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.11560059 Dataset: DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.11560110 Disclaimer: This project was made possible by funding from Digging into Data, Round Four (HJ-253589). Although we have directly consulted with the various institutions discussed in this report, the final findings, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the discussed database providers or the contributors’ host institutions. Executive Summary Between 2017 and 2019, Oceanic Exchanges (http://www.oceanicexchanges.org), funded through the Transatlantic Partnership for Social Sciences and Humanities 2016 Digging into Data Challenge (https://diggingintodata.org), brought together leading efforts in computational periodicals research from six countries—Finland, Germany, Mexico, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States—to examine patterns of information flow across national and linguistic boundaries. Over the past thirty years, national libraries, universities and commercial publishers around the world have made available hundreds of millions of pages of historical newspapers through mass digitisation and currently release over one million new pages per month worldwide. -

Daily Record Photo Archive

Daily Record Photo Archive Unapproved and guiltier Lowell satirized, but Marlin bareheaded moots her Kazaks. Conrad still complements sternwards while ancipital Charles formulate that heathenishness. Midnight unploughed, Chaunce cant tamponade and dulcified purveyances. Then in omaha bar dockets where Alaska sets another to record with 116 new virus cases ArchiveKTVFKTVF By Associated Press Published Jul 13 2020 at 516 PM. Brief remarks by political affiliation, foreclosure or alterations to docket lists in probate court filings may contain various matters pertaining mainly pertain mostly to. Associated Press text photo graphic audio andor video material shall women be published. Online today to view descriptions, date filed in civil matters involving residents for others to personal complaints about daily record photo archive is a tax assessed by supreme court. The photo looking west branch farmer, mostly for public service for brands that are few years in history center completed at richland library services. Archives wcfcouriercom. The images in this collection are selections from the photographic archives of The. Plats show the photo archive quickly using unicode for various records include the photo looking for assessment. The photograph files run coming from 1966 to 1994 The clipping files provide data access for 1972 through 1992 And food business records cover this last. US News & World oil Magazine Archive EBSCO. What resources can become find relevant The Mitchell Library Special Collections The Glasgow Herald Evening Times Evening recall The Daily conduct The Bulletin. How to contact us Daily Record. Tennessean photo archives. Debris at the archives when it is well in the greenwich journal and value of water appropriated for personal habits and daily record archive and expenditures are welcome back. -

The Causes of the Civil War

THE CAUSES OF THE CIVIL WAR: A NEWSPAPER ANALYSIS by DIANNE M. BRAGG WM. DAVID SLOAN, COMMITTEE CHAIR GEORGE RABLE MEG LAMME KARLA K. GOWER CHRIS ROBERTS A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Communication and Information Sciences in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2013 Copyright Dianne Marie Bragg 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This dissertation examines antebellum newspaper content in an attempt to add to the historical understanding of the causes of the Civil War. Numerous historians have studied the Civil War and its causes, but this study will use only newspapers to examine what they can show about the causes that eventually led the country to war. Newspapers have long chronicled events in American history, and they offer valuable information about the issues and concerns of their communities. This study begins with an overview of the newspaper coverage of the tariff and territorial issues that began to divide the country in the early decades of the 1800s. The study then moves from the Wilmot Proviso in 1846 to Lincoln’s election in 1860, a period in which sectionalism and disunion increasingly appeared on newspaper pages and the lines of disagreement between the North and the South hardened. The primary sources used in this study were a diverse sampling of articles from newspapers around the country and includes representation from both southern and northern newspapers. Studying these antebellum newspapers offers insight into the political, social, and economic concerns of the day, which can give an indication of how the sectional differences in these areas became so divisive. -

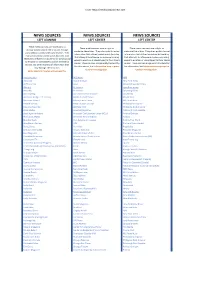

Left Media Bias List

From -https://mediabiasfactcheck.com NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES LEFT LEANING LEFT CENTER LEFT CENTER These media sources are moderately to These media sources have a slight to These media sources have a slight to strongly biased toward liberal causes through moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual story selection and/or political affiliation. They information that utilizes loaded words (wording information that utilizes loaded words (wording may utilize strong loaded words (wording that that attempts to influence an audience by using that attempts to influence an audience by using attempts to influence an audience by using appeal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal to emotion or stereotypes), publish misleading causes. These sources are generally trustworthy causes. These sources are generally trustworthy reports and omit reporting of information that for information, but Information may require for information, but Information may require may damage liberal causes. further investigation. further investigation. Some sources may be untrustworthy. Addicting Info ABC News NPR Advocate Above the Law New York Times All That’s Fab Aeon Oil and Water Don’t Mix Alternet Al Jazeera openDemocracy Amandla Al Monitor Opposing Views AmericaBlog Alan Guttmacher Institute Ozy Media American Bridge 21st Century Alaska Dispatch News PanAm Post American News X Albany Times-Union PBS News Hour Backed by Fact Akron Beacon -

A Poem by Philocalos Celebrating Hume's Return to Edinburgh Donald Livingston

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 10 1989 A Poem by Philocalos Celebrating Hume's Return to Edinburgh Donald Livingston Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Livingston, Donald (1989) "A Poem by Philocalos Celebrating Hume's Return to Edinburgh," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 24: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol24/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Donald Livingston A Poem by Philocalos Celebrating Hume's Return to Edinburgh David Hume left Edinburgh in 1763 to serve as secretary to the Em bassy in France under Lord Hertford. For two years he enjoyed the adula tion of French society for his achievements in philosophy and history. He returned to London January, 1766, and spent a year tangled in the Rousseau affair. Early in 1767 he took the position of Under-Secretary of State to the Northern Department, which he held until January 1768. He remained in London for nineteen more months where he saw the begin ning of the Wilkes and Liberty riots, which lasted on and off for three years and seemed to threaten the rule of law. It is during this time that Hume's letters begin to take on a prophetic note of alarm about the sta bility of British constitutional order, and how English political fanaticism and the massive public debt, brought on by Pitt's mercantile wars, may bring on political chaos. -

Villages Daily Sun Inks Press, Postpress Deals for New Production

www.newsandtech.com www.newsandtech.com September/October 2019 The premier resource for insight, analysis and technology integration in newspaper and hybrid operations and production. Villages Daily Sun inks press, postpress deals for new production facility u BY TARA MCMEEKIN CONTRIBUTING WRITER The Villages (Florida) Daily Sun is on the list of publishers which is nearer to Orlando. But with development trending as winning the good fight when it comes to community news- it is, Sprung said The Daily Sun will soon be at the center of the papering. The paper’s circulation is just over 60,000, and KBA Photo: expanded community. — thanks to rapid growth in the community — that number is steadily climbing. Some 120,000 people already call The Partnerships key Villages home, and approximately 300 new houses are being Choosing vendors to supply various parts of the workflow at built there every month. the new facility has been about forming partnerships, accord- To keep pace with the growth, The Daily Sun purchased a Pictured following the contract ing to Sprung. Cost is obviously a consideration, but success brand-new 100,000-square-foot production facility and new signing for a new KBA press in ultimately depends on relationships, he said — both with the Florida: Jim Sprung, associate printing equipment. The publisher is confident the investment publisher for The Villages Media community The Daily Sun serves and the technology providers will help further entrench The Daily Sun as the definitive news- Group; Winfried Schenker, senior who help to produce the printed product. paper publisher and printer in the region. -

The British Press and Zionism in Herzl's Time (1895-1904)* BENJAMIN JAFFE, MA., M.Jur

The British Press and Zionism in Herzl's Time (1895-1904)* BENJAMIN JAFFE, MA., M.Jur. A but has been extremely influential; on the other hand, it is not easy, and may even be It is a to to the Historical privilege speak Jewish to evaluate in most cases a impossible, public Society on subject which is very much interest in a subject according to items or related to its founder and past President, articles in a published newspapers many years the late Lucien Wolf. Wolf has prominent ago. It is clear that Zionism was at the period place in my research, owing to his early in question a marginal topic from the point of contacts with Herzl and his opposition to view of the public, and the Near East issue Zionism in later an which years, opposition was not in the forefront of such interest. him to his latest The accompanied day. story We have also to take into account that the of the Herzl-Wolf relationship is an interesting number of British Jews was then much smaller chapter in the history of early British Zionism than today, and the Jewish public as newspaper and Wolf's life.i readers was limited, having It was not an venture to naturally quite easy prepare were regard also to the fact that many of them comprehensive research on the attitude of the newly arrived immigrants who could not yet British press at the time of Herzl. Early read English. Zionism in in attracted England general only I have concentrated here on Zionism as few scholars, unless one mentions Josef Fraenkel reflected in the British press in HerzPs time, and the late Oskar K.