A Biography of Madison's Notes of Debates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Shape of the Electoral College

No. 20-366 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States DONALD J. TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, ET AL., Appellants, v. STATE OF NEW YORK, ET AL., Appellees. On Appeal From the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE MICHAEL L. ROSIN IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES PETER K. STRIS MICHAEL N. DONOFRIO Counsel of Record BRIDGET C. ASAY ELIZABETH R. BRANNEN STRIS & MAHER LLP 777 S. Figueroa St., Ste. 3850 Los Angeles, CA 90017 (213) 995-6800 [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................... i INTEREST OF AMICUS .................................................. 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .......................................... 2 ARGUMENT ....................................................................... 4 I. Congress Intended The Apportionment Basis To Include All Persons In Each State, Including Undocumented Persons. ..................... 4 A. The Historical Context: Congress Began to Grapple with Post-Abolition Apportionment. ............................................... 5 B. The Thirty-Ninth Congress Considered—And Rejected—Language That Would Have Limited The Basis of Apportionment To Voters or Citizens. ......... 9 1. Competing Approaches Emerged Early In The Thirty-Ninth Congress. .................................................. 9 2. The Joint Committee On Reconstruction Proposed A Penalty-Based Approach. ..................... 12 3. The House Approved The Joint Committee’s Penalty-Based -

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution ROBERT J. TAYLOR J. HI s YEAR marks tbe 200tb anniversary of tbe Massacbu- setts Constitution, the oldest written organic law still in oper- ation anywhere in the world; and, despite its 113 amendments, its basic structure is largely intact. The constitution of the Commonwealth is, of course, more tban just long-lived. It in- fluenced the efforts at constitution-making of otber states, usu- ally on their second try, and it contributed to tbe shaping of tbe United States Constitution. Tbe Massachusetts experience was important in two major respects. It was decided tbat an organic law should have tbe approval of two-tbirds of tbe state's free male inbabitants twenty-one years old and older; and tbat it sbould be drafted by a convention specially called and chosen for tbat sole purpose. To use the words of a scholar as far back as 1914, Massachusetts gave us 'the fully developed convention.'^ Some of tbe provisions of the resulting constitu- tion were original, but tbe framers borrowed heavily as well. Altbough a number of historians have written at length about this constitution, notably Prof. Samuel Eliot Morison in sev- eral essays, none bas discussed its construction in detail.^ This paper in a slightly different form was read at the annual meeting of the American Antiquarian Society on October IS, 1980. ' Andrew C. McLaughlin, 'American History and American Democracy,' American Historical Review 20(January 1915):26*-65. 2 'The Struggle over the Adoption of the Constitution of Massachusetts, 1780," Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 50 ( 1916-17 ) : 353-4 W; A History of the Constitution of Massachusetts (Boston, 1917); 'The Formation of the Massachusetts Constitution,' Massachusetts Law Quarterly 40(December 1955):1-17. -

The Strange Career of Thomas Jefferson Race and Slavery in American Memory, I94J-I99J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository History Faculty Publications History 1993 The trS ange Career of Thomas Jefferson: Race and Slavery in American Memory Edward L. Ayers University of Richmond, [email protected] Scot A. French Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/history-faculty-publications Part of the Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ayers, Edward L. and Scot A. French. "The trS ange Career of Thomas Jefferson: Race and Slavery in American Memory." In Jeffersonian Legacies, edited by Peter S. Onuf, 418-456. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHAPTER I 4 The Strange Career of Thomas Jefferson Race and Slavery in American Memory, I94J-I99J SCOT A. FRENCH AND EDWARD L. AYERS For generations, the memory of Thomas Jefferson has been inseparable from his nation's memory of race and slavery. Just as Jefferson's words are invoked whenever America's ideals of democracy and freedom need an elo quent spokesman, so are his actions invoked when critics level charges of white guilt, hypocrisy, and evasion. In the nineteenth century, abolitionists used Jefferson's words as swords; slaveholders used his example as a shield. -

John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: a Reappraisal.”

The Historical Journal of Massachusetts “John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: A Reappraisal.” Author: Arthur Scherr Source: Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 46, No. 1, Winter 2018, pp. 114-159. Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/number/date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/. 114 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2018 John Adams Portrait by Gilbert Stuart, c. 1815 115 John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: A Reappraisal ARTHUR SCHERR Editor's Introduction: The history of religious freedom in Massachusetts is long and contentious. In 1833, Massachusetts was the last state in the nation to “disestablish” taxation and state support for churches.1 What, if any, impact did John Adams have on this process of liberalization? What were Adams’ views on religious freedom and how did they change over time? In this intriguing article Dr. Arthur Scherr traces the evolution, or lack thereof, in Adams’ views on religious freedom from the writing of the original 1780 Massachusetts Constitution to its revision in 1820. He carefully examines contradictory primary and secondary sources and seeks to set the record straight, arguing that there are many unsupported myths and misconceptions about Adams’ role at the 1820 convention. -

Madison County Marriages

Volume 19, Issue 2 The Madison County, Florida Genealogical News Apr – Sep 2014 The Madison County, Florida Genealogical News Volume 19, Issue 2 Apr - Sep, 2014 P. O. Box 136 ISSN: 1087-7746 Madison, FL 32341-0136 33 Volume 19, Issue 2 The Madison County, Florida Genealogical News Apr – Sep 2014 Table of Contents Upcoming 2014/2015 Genealogy Conferences ................................................................................................. 34 Extracts from the New Enterprise, Madison, FL, Apr 1905 .......................................................................... 35 Circus Biography, Mattie Lee Price ......................................................................................................................... 40 Francis Eppes (1865-1929) ........................................................................................................................................ 42 Death of a Grandson of Jefferson .............................................................................................................................. 43 Boston Cemetery, Boston, Thomas County, Georgia ....................................................................................... 44 How Well do you Understand Family Terminology? ..................................................................................... 44 Shorter College ................................................................................................................................................................. 47 Extracts from Madison County -

The Federal Constitution and Massachusetts Ratification : A

, 11l""t,... \e ,--.· ', Ir \" ,:> � c.'�. ,., Go'.l[f"r•r•r-,,y 'i!i • h,. I. ,...,,"'P�r"'T'" ""J> \S'o ·� � C ..., ,' l v'I THE FEDERAL CONSTlTUTlON \\j\'\ .. '-1',. ANV /JASSACHUSETTS RATlFlCATlON \\r,-,\\5v -------------------------------------- . > .i . JUN 9 � 1988 V) \'\..J•, ''"'•• . ,-· �. J ,,.._..)i.�v\,\ ·::- (;J)''J -�·. '-,;I\ . � '" - V'-'� -- - V) A TEACHING KIT PREPAREV BY � -r THE COIJMOMVEALTH M,(SEUM ANV THE /JASSACHUSETTS ARCHIVES AT COLUM.BIA POINf ]') � ' I � Re6outee Matetial6 6ot Edueatot6 and {I · -f\ 066ieial& 6ot the Bieentennial 06 the v-1 U.S. Con&titution, with an empha6i& on Ma&&aehu&ett6 Rati6ieation, eontaining: -- *Ma66aehu6ett& Timeline *Atehival Voeument6 on Ma&&aehu&ett& Rati6ieation Convention 1. Govetnot Haneoek'6 Me&6age. �����4Y:t4���� 2. Genetal Coutt Re6olve& te C.U-- · .....1. *. Choo6ing Velegate& 6ot I\) Rati6ieation Convention. 0- 0) 3. Town6 &end Velegate Name&. 0) C 4. Li6t 06 Velegate& by County. CJ) 0 CJ> c.u-- l> S. Haneoek Eleeted Pte6ident. --..J s:: 6. Lettet 6tom Elbtidge Getty. � _:r 7. Chatge6 06 Velegate Btibety. --..J C/)::0 . ' & & • o- 8 Hane oe k Pt op o 6e d Amen dme nt CX) - -j � 9. Final Vote on Con&titution --- and Ptopo6ed Amenwnent6. Published by the --..J-=--- * *Clue6 to Loeal Hi&toty Officeof the Massachusetts Secretary of State *Teaehing Matetial6 Michaelj, Connolly, Secretary 9/17/87 < COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS !f1Rl!j OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE CONSTITUTtON Michael J. Connolly, Secretary The Commonwealth Museum and the Massachusetts Columbia Point RATIFICATION OF THE U.S. CONSTITUTION MASSACHUSETTS TIME LINE 1778 Constitution establishing the "State of �assachusetts Bay" is overwhelmingly rejected by the voters, in part because it lacks a bill of rights. -

Francis Eppes (1801-1881), Pioneer of Florida

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 5 Number 2 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 5, Article 7 Issue 2 1926 Francis Eppes (1801-1881), Pioneer of Florida Nicholas Ware Eppes Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Eppes, Nicholas Ware (1926) "Francis Eppes (1801-1881), Pioneer of Florida," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 5 : No. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol5/iss2/7 Eppes: Francis Eppes (1801-1881), Pioneer of Florida 94 FRANCIS EPPES (1801-1881), PIONEER OF FLORIDA In the White House, in Washington, in the year 1801, Thomas Jefferson waited anxiously for tidings from Monticello ; for there his beloved daughter, the beautiful Maria Jefferson Eppes, was waging the world-old battle for life. For hours the great states- man had been walking the floor, too miserable for sleep. Then came a knock at the door and Peter handed him a scrap of paper on which was hurriedly scrawled these words, “Mother and boy doing well- a fine hearty youngster, with hazel eyes and to his mother’s delight he has hair like your own. She sends dear love to the Father she is longing to see.” The night was almost over and Thomas Jefferson, after a prayer of thanksgiving, slept soundly. Two happy years passed for this devoted family and then Mrs. -

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C. -

The Other Madison Problem

THE OTHER MADISON PROBLEM David S. Schwartz* & John Mikhail** The conventional view of legal scholars and historians is that James Madison was the “father” or “major architect” of the Constitution, whose unrivaled authority entitles his interpretations of the Constitution to special weight and consideration. This view greatly exaggerates Madison’s contribution to the framing of the Constitution and the quality of his insight into the main problem of federalism that the Framers tried to solve. Perhaps most significantly, it obstructs our view of alternative interpretations of the original Constitution with which Madison disagreed. Examining Madison’s writings and speeches between the spring and fall of 1787, we argue, first, that Madison’s reputation as the father of the Constitution is unwarranted. Madison’s supposedly unparalleled preparation for the Constitutional Convention and his purported authorship of the Virginia plan are unsupported by the historical record. The ideas Madison expressed in his surprisingly limited pre-Convention writings were either widely shared or, where more peculiar to him, rejected by the Convention. Moreover, virtually all of the actual drafting of the Constitution was done by other delegates, principally James Wilson and Gouverneur Morris. Second, we argue that Madison’s recorded thought in this critical 1787 period fails to establish him as a particularly keen or authoritative interpreter of the Constitution. Focused myopically on the supposed imperative of blocking bad state laws, Madison failed to diagnose the central problem of federalism that was clear to many of his peers: the need to empower the national government to regulate the people directly. Whereas Madison clung to the idea of a national government controlling the states through a national legislative veto, the Convention settled on a decidedly non-Madisonian approach of bypassing the states by directly regulating the people and controlling bad state laws indirectly through the combination of federal supremacy and preemption. -

Accounts Committee, 70. 186 Adams. Abigail, 56 Adams, Frank, 196

Index Accounts Committee, 70. 186 Appropriations. Committee on (House) Adams. Abigail, 56 appointment to the, 321 Adams, Frank, 196 chairman also on Rules, 2 I I,2 13 Adams, Henry, 4 I, 174 chairman on Democratic steering Adams, John, 41,47, 248 committee, 277, 359 Chairmen Stevens, Garfield, and Adams, John Quincy, 90, 95, 106, 110- Randall, 170, 185, 190, 210 111 created, 144, 167. 168, 169, 172. 177, Advertisements, fS3, I95 184, 220 Agriculture. See also Sugar. duties on estimates government expenditures, 170 Jeffersonians identified with, 3 1, 86 exclusive assignment to the, 2 16, 32 1 prices, 229. 232, 261, 266, 303 importance of the, 358 tariffs favoring, 232, 261 within the Joint Budget Committee, 274 Agriculture Department, 303 loses some jurisdiction, 2 10 Aid to Families with Dependent Children members on Budget, 353 (AFDC). 344-345 members on Joint Study Committee on Aldrich, Nelson W., 228, 232. 241, 245, Budget Control, 352 247 privileged in reporting bills, 185 Allen, Leo. 3 I3 staff of the. 322-323 Allison, William B., 24 I Appropriations, Committee on (Senate), 274, 352 Altmeyer, Arthur J., 291-292 American Medical Association (AMA), Archer, William, 378, 381 Army, Ci.S. Spe also War Department 310, 343, 345 appropriation bills amended, 136-137, American Newspaper Publishers 137, 139-140 Association, 256 appropriation increases, 127, 253 American Party, 134 Civil War appropriations, 160, 167 American Political Science Association, Continental Army supplies, I7 273 individual appropriation bills for the. American System, 108 102 Ames, Fisher, 35. 45 mobilization of the Union Army, 174 Anderson, H. W., 303 Arthur, Chester A,, 175, 206, 208 Assay omces, 105, 166 Andrew, John, 235 Astor, John Jacob, 120 Andrews, Mary. -

TO SIGN OR NOT to SIGN Lesson Plan to SIGN OR NOT to SIGN

TO SIGN OR NOT TO SIGN Lesson Plan TO SIGN OR NOT TO SIGN ABOUT THIS LESSON AUTHOR On Constitution Day, students will examine the role of the people in shaping the United States Constitution. First, students National Constitution Center will respond to a provocative statement posted in the room. They will then watch a video that gives a brief explanation of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, or listen as the video transcript is read aloud. A Constitution poster is provided so students can examine Article VII and discuss it as a class. The elementary and middle school educator will then guide students through a read-aloud play depicting two Constitutional Convention delegates who disagreed about ratifying the Constitution. High school students will review support materials and have a class debate about why delegates should or should not have signed the Constitution in 1787. The class will then discuss the ratification process. The lesson closes with an opportunity for students to sign the Constitution, if they choose, and to discuss what it means to sign or not sign. TO SIGN OR NOT TO SIGN 2 BaCKGROUND GRADE LEVEL(S) September 17, 1787 was the final day of the Constitutional Convention, when 39 of the men present in Philadelphia Elementary, Middle, High School chose to sign the document. Signing put their reputations on the line. Their signatures gave weight to the document, ClaSSROOM TIME but it was the subsequent ratification contest that really 45 minutes mattered. Ratification embodied the powerful idea of popular sovereignty—government by the people—that has been at the heart of the Constitution from its inception until today. -

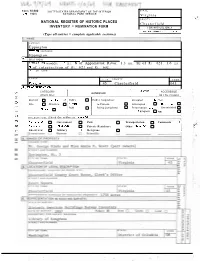

Nomination Form for Nps Use Only

STATE: Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Doc. 1968) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Virginia COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Chesterfield INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) COMMON: Eppington AND/OR HISTORIC: Epping ton I2, LOCATION P.......,, ~'TREET NUMBER: .7 mi. N of Appomattox River, 1.3 mi. SE of Rt. 621, 1.6 mi. S of intersection of Rt. 621 and Rt. 602. CITY OR TOWN: STATE CODE COUNTY: CODE Vir~inia 45 Chesterfield 041 CLASSIFICATION -..., .. CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District Building Public Public Acquisition: Occupied Q Yes: Site Structure Private In Process Unoccupied Restrlcted Both Being Considered Preservation work Unrestricted Obiect In progress N,,, PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Approprlale) Agricultural Government Park Transportation Comments a Cornrnerciol Industrial Private Residence Other (specrfy) Educational Military D Religious (Check 0"s) cONO'TiON Exceile;l,;, ;"e'one) Fair Oaterioroted Ruin, U Unexposed 1 1 (Check 0"s) INTEGRITY un~ltwed MOV-~ 0 Originel sits DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (Ifknown) PHYSICAL APPEhRINCE Eppington ffawes a three-bay, two-and-a-half story central block with hipped roof, dormers, modillioned cornice, and flanking one-story wings. The first floor front of the central block has been altered by board and batten siding and a rather dcep, full-length porch. ThecentralU.eck is framed with two tall exterior end chimneys which rise from the roof of the wings. The roofline of the wings terminates in a low-pitched hip which softens the effect of the rather.steeply pitched roof of the central block.