Henry George and the Crisis of Inequality Columbia University Press, New York, 2015, Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Lectures on Urban Economics

2020 Lectures on Urban Economics Lecture 5: Cities in Developing Countries J. Vernon Henderson (LSE) 9 July 2020 Outline of talk • Urbanization: Moving to cities • Where are the frontiers of urbanization • Does the classic framework apply? • “Spatial equilibrium” in developing countries • Issues and patterns • Structural modelling • Data needed • Relevant questions and revisions to baseline models • Within cities • Building the city: investment in durable capital • Role of slums • Land and housing market issues Frontiers of urbanization • Not Latin America and not much of East and West Asia • (Almost) fully urbanized (60-80%) with annual rate of growth in urban share growth typically about 0.25% • Focus is on clean-up of past problems or on distortions in markets • Sub-Saharan Africa and South and South-East Asia • Urban share 35-50% and annual growth rate in that share of 1.2- 1.4% • Africa urbanizing at comparatively low-income levels compared to other regions today or in the past (Bryan at al, 2019) • Lack of institutions and lack of money for infrastructure “needs” Urbanizing while poor Lagos slums, today Sewers 1% coverage London slums, 120 years ago Sewer system: 1865 Models of urbanization • Classic dual sector • Urban = manufacturing; rural = agriculture • Structural transformation • Closed economy: • Productivity in agriculture up, relative to limited demand for food. • Urban sector with productivity growth in manufacturing draws in people • Open economy. • “Asian tigers”. External demand for manufacturing (can import food in theory) • FDI and productivity growth/transfer Moving to cities: bright lights or productivity? Lack of structural transformation • Most of Africa never really has had more than local non-traded manufactures. -

Henry George's Labor Theory of Value: He Saw the Entrepreneurs and Workers As Employers of Capital and Land, and Not the Reverse Author(S): Robert J

American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Inc. Henry George's Labor Theory of Value: He Saw the Entrepreneurs and Workers as Employers of Capital and Land, and Not the Reverse Author(s): Robert J. Rafalko Source: American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Vol. 48, No. 3 (Jul., 1989), pp. 311-320 Published by: American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3487369 . Accessed: 20/12/2013 16:34 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Economics and Sociology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 149.10.125.20 on Fri, 20 Dec 2013 16:34:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions HenryGeorge's Labor Theory of Value: He Saw the Entrepreneursand Workersas Employersof Capitaland Land, and Not the Reverse By ROBERTJ. RAFALKO* ABSTRACT.Henry George, the 19th century American economistand socialphi- losopher, saw the problem of protecting the working peoples' wages and jobs one of distributive justice. He attacked as fallacious the idea that equality of opportunityto workwas a 'privilege "accordedto labor. -

544 Urban Growth

544 urban growth changes in spatially delineated public goods. the physical structure of cities and how it may change as International Economic Review 45, 1047-77. cities grow. It also focuses on how changes in commuting Tolley, G. 1974. The welfare economics of city bigness. costs, as well as the industrial composition of national Journal of Urban Economics 1, 324-45. output and other technological changes, have affected the United Nations Population Division. 2004. World Population growth of cities. Another direction has focused on Prospects: The 2004 Revision Population Database. Online. understanding the evolution of systems of cities - that Available at http://esa.un.orglunpp, accessed 28 June is, how cities of different sizes interact, accommodate and 2005. share different functions as the economy develops and what the properties of the size distribution of urban areas are for economies at different stages of development. Do the properties of the system of cities and of city size urban growth distribution persist while national population is growing? Urban growth - the growth and decline of urban Finally, there is a literature that studies the link between areas - as an economic phenomenon is inextricably urban growth and economic growth. What restrictions linked with the process of urbanization. Urbanization does urban growth impose on economic growth? What itself has punctuated economic development. The spatial economic functions are allocated to cities of different distribution of economic activity, measured in terms of sizes in a growing economy? Of course, all of these lines population, output and income, is concentrated. The of inquiry are closely related and none of them may be patterns of such concentrations and their relationship fully understood, theoretically and empirically, on its to measured economic and demographic variables con own. -

Well Isnjt That Spatial?! Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Well Isn’tThat Spatial?! Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics: A View From Economic Theory Marcus Berlianty February 2005 I thank Gilles Duranton, Sukkoo Kim, Fan-chin Kung and Ping Wang for comments, implicating them only for baiting me. yDepartment of Economics, Washington University, Campus Box 1208, 1 Brookings Drive, St. Louis, MO 63130-4899 USA. Phone: (314) 935-8486, Fax: (314) 935-4156, e-mail: [email protected] 1 As a younger and more naïve reviewer of the …rst volume of the Handbook (along with Thijs ten Raa, 1994) more than a decade ago, it is natural to begin with a comparison for the purpose of evaluating the progress or lack thereof in the discipline.1 Then I will discuss some drawbacks of the New Economic Geography, and …nally explain where I think we should be heading. It is my intent here to be provocative2, rather than to review speci…c chapters of the Handbook. First, volume 4 cites Masahisa Fujita more than the one time he was cited in volume 1. Volume 4 cites Ed Glaeser more than the 4 times he was cited in volume 3. This is clear progress. Second, since the …rst volume, much attention has been paid by economists to the simple question: “Why are there cities?” The invention of the New Economic Geography represents an important and creative attempt to answer this question, though it is not the unique set of models capable of addressing it. -

The Empirics of New Economic Geography ∗

The Empirics of New Economic Geography ∗ Stephen J Redding LSE, Yale School of Management and CEPR y February 28, 2009 Abstract Although a rich and extensive body of theoretical research on new economic geography has emerged, empirical research remains comparatively less well developed. This paper reviews the existing empirical literature on the predictions of new economic geography models for the distribution of income and production across space. The discussion highlights connections with other research in regional and urban economics, identification issues, potential alternative explanations and possible areas for further research. Keywords: New economic geography, market access, industrial location, multiple equilibria JEL: F12, F14, O10 ∗This paper was produced as part of the Globalization Programme of the ESRC-funded Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics. Financial support under the European Union Research Training grant MRTN-CT-2006-035873 is also gratefully acknowledged. I am grateful to a number of co-authors and colleagues for insight, discussion and comments, including in particular Tony Venables and Gilles Duranton, and also Guy Michaels, Henry Overman, Esteban Rossi-Hansberg, Peter Schott, Daniel Sturm and Nikolaus Wolf. I bear sole responsibility for the opinions expressed and any errors. yDepartment of Economics, London School of Economics, Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom. Tel: + 44 20 7955 7483, Fax: + 44 20 7955 7595, Email: s:j:redding@lse:ac:uk. Web: http : ==econ:lse:ac:uk=staff=sredding=. 1 1 Introduction Over the last two decades, the uneven distribution of economic activity across space has received re- newed attention with the emergence of the “new economic geography” literature following Krugman (1991a). -

810 South Sterling Ave. Tampa, FL 33609 [email protected]

810 South Sterling Ave. Tampa, FL 33609 813.289.88L.L, [email protected] - RBANECONOMICS.COM ECONOMICS INC. MICHAEL A. MCELVEEN, MAI, CCIM, CRE President Urban Economics, Inc. 810 South Sterling Avenue Tampa, FL 33609-4516 Urban Economics, Inc. - Tampa, Florida - Michael A. McElveen is president of Urban Economics, Incorporat ed, a real estate consultancy providing econometrics, valuation, spat ia l analytics, economic impact and st igma effect advice and opinions for 31 years. The focus of Michael A. McElveen has been expert witness t estimony, having testified numerous times at either a jury trial , hearing or by deposition. Mr. McElveen has been accepted by the Ninth Jud icial Circuit Court of Florida an d the Thirteenth Judicial Circuit Court as an expert in the use of econometrics in real estate. Mr. McElveen has performed the following econometric studies: • Econometric study of the marginal impact of an additional 18-hole golf course and equestrian facility o n the value of residential lots, Lake County, FL; • Sales price index trend of fractured condominium sales in O sceola County; • Econometric study of the rent effect of deficient parking at neighborhood retail centers, Charlotte County, FL; • Economet ric study of the sales price effect of location and community w aterfront in Martin County, FL; and • Hedonic regression model analysis of the sales price effect vehicul ar traffic volume and roadway elevation on nearby ho mes in Duval County, Florida. Ed uca ti o n Bachelo r of Arts Finance, University of South Bachelor of Science, Florida State University Florida Professional Associations Appraisal Institute (MAI), Certificate No. -

Henry George: the Theory of Distribution in Progress and Poverty

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2007-07-01 Henry George: The Theory of Distribution in Progress and Poverty Phillip J. Bryson [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Economics Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Bryson, Phillip J., "Henry George: The Theory of Distribution in Progress and Poverty" (2007). Faculty Publications. 248. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/248 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. HENRY GEORGE: THE THEORY OF DISTRIBUTION IN PROGRESS AND POVERTY Phillip J. Bryson, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA ABSTRACT The core of Henry George’s economic theory appeared in his most widely-read book, Progress and Poverty. On the basis of his dramatic “single tax” theory, his work became widely known and gained some avid followers who endeavored to base policy on it. But the work was also of value in George’s day and of interest in our day because of its economic content. George was not a part of the academic economics establishment of his day and his theory was of strictly classical methodology, but it still had much to commend it. A simple model to present his concepts in more modern form is developed. On the basis of the diagrammatic techniques involved, George’s theory of distribution is presented and evaluated. Keywords: Theory of distribution, classical economics, economic growth, wages fund, wages, interest, rent, poverty. -

Economic Geography, Jobs, and Regulations: the Value of Land and Housing

Economic Geography, Jobs, and Regulations: The Value of Land and Housing Nils Kok Paavo Monkkonen John M. Quigley Maastricht University University of Hong Kong University of California Netherlands Hong Kong Berkeley, CA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] February 2011 Analyses of the determinants of land prices in urban areas typically base inferences on housing transactions which combine payments for land and long-lived improvements. These inferences, in turn, are based upon assumptions about the production function for housing and the appropriate aggregation of non-land inputs. In contrast, we investigate directly the determinants of urban land prices. We assemble more than 7,000 land transactions in the San Francisco Bay Area during the 1990-2009 period, and we analyze the link between the physical access of sites, the topographical and demographic characteristics of their local environment, and the prices of vacant land on those sites. We investigate in detail the link between variations in the quality of public services and the value of developable land. Most importantly, our analysis documents the powerful link between variations in the regulatory environment within a metropolitan area and the prices commanded by raw land as an input to residential or commercial development. Finally, we relate these large variations in land prices to the prices paid by consumers for housing in the region. JEL Codes: D40, L51, R31 Keywords: Geography, Housing Supply, Land Prices, Land-Use Regulation Financial support for this research was provided by the Berkeley Program for Housing and Urban Policy and the European Property Research Institute at Maastricht University. -

Henry George Antiprotectionist Giant of American Economics

Economic Insights FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF DALLAS VOLUME 10, NUMBER 2 Henry George Antiprotectionist Giant of American Economics Americans are again confronted, both Today’s policy discussions are often domestically and internationally, with the argued as if the issue under considera- clash of protectionist and free trade senti- tion is unique to our time. Because we often forget—or never knew—the rel- ment. A deeply divided U.S. House just evant history, we can fail to see that barely passed the Central American Free almost every policy argument has his- Trade Agreement. Politicians who a few years torical precedent. This is certainly true back supported the North American Free of the hot-button issues of globalization Trade Agreement now adamantly oppose and protectionism. Although many be- CAFTA. Americans are torn between enjoying lieve them unique to our day, antiglob- alization—with its concomitant protec- the benefits of globalization, with its tionist sentiments—salts human history. increased consumer choices and lower Mercantilist doctrine, which is pro- prices, and worrying about the costs to the tectionist, dates to mid-17th century nation that some claim come with global free Europe. As international trade grew, so, trade. too, did the demand for government There is nothing new about this clash of intervention to protect domestic manu- Library, The New York Science, Industry & Business Library, Lenox and Tilden Foundations Astor, factures by discouraging imports and ideas, as this latest points Henry George Economic Insights subsidizing exports. Even nations com- out; they have been vigorously debated mitted to obtaining the benefits of free before, most notably during the late 19th trade have not been immune to mer- ing in California a decade after the century. -

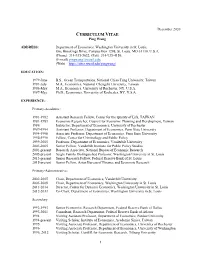

CURRICULUM VITAE Ping Wang

December 2020 CURRICULUM VITAE Ping Wang ADDRESS: Department of Economics, Washington University in St. Louis, One Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1208, St. Louis, MO 63130, U.S.A. (Phone) 314-935-5632; (Fax) 314-935-4156; (E-mail) [email protected]; (Web) https://sites.wustl.edu/pingwang/ EDUCATION: 1979-June B.S., Ocean Transportation, National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan 1981-July M.A., Economics, National Chengchi University, Taiwan 1986-May M.A., Economics, University of Rochester, NY, U.S.A. 1987-May Ph.D., Economics, University of Rochester, NY, U.S.A. EXPERIENCE: Primary-Academic: 1981-1982 Assistant Research Fellow, Center for the Quality of Life, TAIWAN 1981-1983 Economic Researcher, Council for Economic Planning and Development, Taiwan 1986 Instructor, Department of Economics, University of Rochester 1987-1994 Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Penn State University 1994-1998 Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Penn State University 1994-1998 Fellow, Center for Criminology and Public Policy 1999-2005 Professor, Department of Economics, Vanderbilt University 2001-2005 Senior Fellow, Vanderbilt Institute for Public Policy Studies 2001-present Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research 2005-present Seigle Family Distinguished Professor, Washington University in St. Louis 2013-present Senior Research Fellow, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 2015-present Senior Fellow, Asian Bureau of Finance and Economic Research Primary-Administrative: 2002-2005 Chair, Department of Economics, Vanderbilt University -

'Common Rights' - What Are They?

'Common Rights' - What are they? An investigation into rights of passage and rights of land use (or rights of common) Alan Shelley PG Dissertation in Landscape Architecture Cheltenham & Gloucester College of Higher Education April2000 Abstract There is a level of confusion relating to the expression 'common' when describing 'common rights'. What is 'common'? Common is a word which describes sharing or 'that affecting all alike'. Our 'common humanity' may be a term used to describe people in general. When we refer to something 'common' we are often saying, or implying, it is 'ordinary' or as normal. Mankind, in its earliest civilisation formed societies, usually of a family tribe, that expanded. Society is principled on community. What are 'rights'? Rights are generally agreed practices. Most often they are considered ethically, to be moral, just, correct and true. They may even be perceived, in some cases, to include duty. The evolution of mankind and society has its origins in the land. Generally speaking common rights have come from land-lore (the use of land). Conflicts have evolved between customs and the statutory rights of common people (the people of the commons). This has been influenced by Church (Canonical) law, from Roman formation, statutory enclosures of land and the corporation of local government. Privilege, has allowed 'freemen', by various customs, certain advantages over the general populace, or 'common people'. Unfortunately, the term no longer describes a relationship of such people with the land, but to their nationhood. Contents Page Common Rights - What are they?................................................................................ 1 Rights of Common ...................................................................................................... 4 Woods and wood pasture ............................................................................................ -

The Last Tax: Henry George and the Social Politics of Land Reform in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era

The Last Tax: Henry George and the Social Politics of Land Reform in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of History Michael Willrich, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Alexandra Wagner Lough August 2013 This dissertation, directed and approved by Alexandra Wagner Lough’s Committee, has been accepted and approved by the Faculty of Brandeis University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Malcolm Watson, Dean Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Dissertation Committee: Michael Willrich, Department of History Mark Hulliung, Department of History Daniel T. Rodgers, Department of History, Princeton University Copyright 2013 Alexandra Wagner Lough Doctor of Philosophy Acknowledgments This project properly began in 2004 when I was an undergraduate at the University of Pacific in Stockton, California and decided to write a history thesis on Henry George. As such, it seems fitting to begin by thanking my two favorite professors at Pacific, Caroline Cox and Robert Benedetti. Their work inspired my own and their encouragement and advice led me to pursue graduate work in history at Brandeis University. I am forever grateful for their support. I consider myself extremely fortunate to have been admitted into the Ph.D. program in American History at Brandeis. Not only have I received top-notch instruction from brilliant faculty, but I also have received generous funding. I want to extend my gratitude to Rose and Irving Crown and the Crown family for the fellowship that financed my graduate education.