Nber Working Paper Series Gross Capital Inflows To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATO's Futures Through Russian and Chinese Beholders' Eyes

HCSS SECURITY NATO’s Futures through Russian and Chinese Beholders’ Eyes HCSS helps governments, non-governmental organizations and the private sector to understand the fast-changing environment and seeks to anticipate the challenges of the future with practical policy solutions and advice. NATO’s Futures through Russian and Chinese Beholders’ Eyes HCSS Security The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies ISBN/EAN: 9789492102720 Authors: Yar Batoh, Stephan De Spiegeleire, Daria Goriacheva, Yevhen Sapolovych, Marijn de Wolff and Frank Bekkers. Project Team: Yar Batoh, Stephan De Spiegeleire, Daria Goriacheva, Yevhen Sapolovych, Marijn de Wolff, Patrick Bolder, Frank Bekkers. 2019 © The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced and/or published in any form by print, photo print, microfilm or any other means without prior written permission from HCSS. All images are subject to the licenses of their respective owners. DISCLAIMER: The research for and production of this report has been conducted within the PROGRESS research framework agreement. Responsibility for the contents and for the opinions expressed, rests solely with the authors and does not constitute, nor should it be construed as, an endorsement by the Netherlands Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defense. Design: Mihai Eduard Coliban (layout) and Constantin Nimigean (typesetting). The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies [email protected] hcss.nl Lange Voorhout 1 2514EA The Hague The Netherlands HCSS SECUrity NATO’s Futures through Russian and Chinese Beholders’ Eyes* * The title was ‘borrowed’ from Vojtech Mastny, Nato in the Beholder’s Eye: Soviet Perceptions and Policies, 1949-56, Working Paper ;No. -

Higher Education Management and Policy in Higher Education Journal of the Programme Higher Education Management and Policy on Institutional Management Volume 14, No

EDUCATION AND SKILLS « Journal of the Programme on Institutional Management 14, No. 1 Higher Education Management and Policy Volume in Higher Education Journal of the Programme Higher Education Management and Policy on Institutional Management Volume 14, No. 1 in Higher Education CONTENTS There are Mergers, and there are Mergers: The Forms of Inter-institutional Combination Daniel W. Lang 11 Higher Education Marketization and the Changing Governance in Higher Education: A Comparative Study Management and Policy Joshua K.H. Mok and Eric H.C. Lo 51 The Rationale Behind Public Funding of Private Universities in Japan Masateru Baba 83 EDUCATION AND SKILLS Measuring Internationalisation in Educational Institutions Case Study: French Management Schools Claude Échevin and Daniel Ray 95 Coping with the New Challenges in Managing a Russian University Evgeni Kniazev 109 Book Review David Palfreyman 127 Index to Volumes 9-13 135 Index to Volume 13 147 Subscribers to this printed periodical are entitled to free online access. If you do not yet have online access via your institution's network contact your librarian or, if you subscribe personally, send an email to [email protected] www.oecd.org ISSN 1682-3451 89 2002 01 1 P 2002 SUBSCRIPTION imhe (3 ISSUES) -:HRLGSC=XYZUUU: Volume 14, No. 1 Volume 14, No. 1 © OECD, 2002. © Software: 1987-1996, Acrobat is a trademark of ADOBE. All rights reserved. OECD grants you the right to use one copy of this Program for your personal use only. Unauthorised reproduction, lending, hiring, transmission or distribution of any data or software is prohibited. You must treat the Program and associated materials and any elements thereof like any other copyrighted material. -

Capital Flows and Emerging Market Economies

Committee on the Global Financial System CGFS Papers No 33 Capital flows and emerging market economies Report submitted by a Working Group established by the Committee on the Global Financial System This Working Group was chaired by Rakesh Mohan of the Reserve Bank of India January 2009 JEL Classification: F21, F32, F36, G21, G23, G28 Copies of publications are available from: Bank for International Settlements Press & Communications CH 4002 Basel, Switzerland E mail: [email protected] Fax: +41 61 280 9100 and +41 61 280 8100 This publication is available on the BIS website (www.bis.org). © Bank for International Settlements 2009. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is cited. ISBN 92-9131-786-1 (print) ISBN 92-9197-786-1 (online) Contents A. Introduction......................................................................................................................1 The macroeconomic effects of capital account liberalisation ................................ 1 An outline of the Report .........................................................................................5 B. The macroeconomic context of capital flows...................................................................7 Introduction ............................................................................................................7 Capital flows in historical perspective ....................................................................8 Capital flows in the 2000s ....................................................................................17 -

One Hundred Twelfth Congress of the United States of America

H. R. 3630 One Hundred Twelfth Congress of the United States of America AT THE SECOND SESSION Begun and held at the City of Washington on Tuesday, the third day of January, two thousand and twelve An Act To provide incentives for the creation of jobs, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012’’. (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents for this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. TITLE I—EXTENSION OF PAYROLL TAX REDUCTION Sec. 1001. Extension of payroll tax reduction. TITLE II—UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFIT CONTINUATION AND PROGRAM IMPROVEMENT Sec. 2001. Short title. Subtitle A—Reforms of Unemployment Compensation to Promote Work and Job Creation Sec. 2101. Consistent job search requirements. Sec. 2102. State flexibility to promote the reemployment of unemployed workers. Sec. 2103. Improving program integrity by better recovery of overpayments. Sec. 2104. Data exchange standardization for improved interoperability. Sec. 2105. Drug testing of applicants. Subtitle B—Provisions Relating To Extended Benefits Sec. 2121. Short title. Sec. 2122. Extension and modification of emergency unemployment compensation program. Sec. 2123. Temporary extension of extended benefit provisions. Sec. 2124. Additional extended unemployment benefits under the Railroad Unem- ployment Insurance Act. Subtitle C—Improving Reemployment Strategies Under the Emergency Unemployment Compensation Program Sec. 2141. Improved work search for the long-term unemployed. Sec. -

ASEAN Country Profile : Malaysia

__ PRIVATE INVESTMENT AND TRADE OPPORTUNITIES ECONOMIC BRIEF NO. 4 ASEAN COUNTRY PROFILE MALAYSIA: THE NEXT NIE? East-West Center The P1TCU Economic firizj Series The Private Investment and Trade Opportunities (PITO) project seeks to expand and enhance business ties between the U.5. and ASEAN private sectors. P110 is funded by a grant from the United States Agency for International DQ- velopment (AID) with contributions from the U.S. and ASEAN public and pri- vate sectors. The PITO Economic Brief series, which is published under this project, is designed to address and analyze timely and important policy issues in the ASEAN region that are of interest to the private sectors in the United States and ASEAN. It is also intended to familiarise the U.S. private sector with the ASEAN region, identify growth sectors, and anticipate economic trends. The PflU Economic rilf series is edited and published by the Institute for Economic Development urid Policy of the East-West Center, which coordinates the Trade Policy and Problem hesolu- tion Component of PITO. To obtain a copy of a PITO Economic Brief, please write to: 1- ditor Institute for Economic Development and Policy East-West Center 1777 East-West Road Honolulu, HI 96848 United States of America PRIVATE INVESTMENT AND TRADE OPPORTUNITIES ECONOMIC BRIEF NO. 4 ASEAN COUNTRY PROFILE MALAYSIA: THE NEXT NIE? East-West Center Institute for Economic Development and Policy N?' KDREA I eiiing r 5. KOREA J APAN • ^ ^• rr^kyo CHINA i' 4 HONG i ,^1 : KONG TAIWAN BURMA` ` "; I..AQS Pacfii c Ure f i VIETNAM THAILAN 1 PIIILIYPINE5 \ r ^:^^ i 1 MartiI Bangkok ,' KAA_ PLICHEA BRUNEI (/J/ Bandar Ir Seri 444^^^ Begawan ''' MALAYSI A`yn^f a .::•.•Kuala I-umpur ,; ^,y^fFj . -

ASEAN in Transformation: Textiles, Clothing and Footwear

TEXTILES, CLOTHING AND FOOTWEAR: REFASHIONING THE FUTURE ASEAN IN TRANSFORMATION TEXTILES, CLOTHING AND FOOTWEAR: REFASHIONING THE FUTURE 1 x TEXTILES, CLOTHING AND FOOTWEAR: REFASHIONING THE FUTURE July 2016 Jae-Hee Chang, Gary Rynhart and Phu Huynh Bureau for Employers’ Activities (ACT/EMP), Working Paper No 14 International Labour Office i ASEAN IN TRANSFORMATION Copyright © International Labour Organization 2016 First published (2016) Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Chang, Jae-Hee; Huynh, Phu; Rynhart, Gary ASEAN in transformation : textiles, clothing and footwear: refashioning the future / Jae-Hee Chang, Phu Huynh, Gary Rynhart ; International Labour Office, Bureau for Employers’ Activities (ACT/EMP) ; ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. - Geneva: ILO, 2016 (Bureau for Employers’ Activities (ACT/EMP) working -

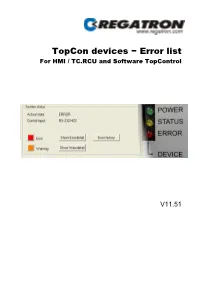

Topcon Devices − Error List for HMI / TC.RCU and Software Topcontrol

TopCon devices − Error list For HMI / TC.RCU and Software TopControl V11.51 TopCon – Error list 1 1. General information © 2021 Regatron AG This document is protected by copyright. All rights, including translation, re-printing and duplication of this manual or parts of it, reserved. No part of this work is allowed to be reproduced, processed, copied or distributed in any form, also not for educational purposes, without the written approval of Regatron. This information in this documentation corresponds to the development situation at the time of going to print and is therefore not of a binding nature. Regatron AG reserves the right to make changes at any time for the purpose of technical progress or product improvement, without stating the reasons. In general we refer to the applicable issue of our “Terms of delivery”. 2 / 75 2021-08-17 TopCon – Error list 1 Identification Manufacturer Information on the manufacturer Regatron AG Feldmuehlestrasse 50 9400 Rorschach SWITZERLAND +41 71 846 67 44 www.regatron.com [email protected] Tab. 1 Instructions Document identification Identifier TopCon devices − Error list Error list Version V11.51 Tab. 2 Open questions In you have any questions, your TopCon sales partner will be pleased to be of assistance. 3 / 75 2021-08-17 TopCon – Error list 1 Table of contents 1. GENERAL INFORMATION .......................................................................................... 2 Identification ................................................................................................................................................... -

Advancing Digital Financial Inclusion in ASEAN

Public Disclosure Authorized Advancing Digital Financial Inclusion in ASEAN Public Disclosure Authorized Policy and Regulatory Enablers Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Advancing Digital Financial Inclusion in ASEAN report was written on the initiative of the ASEAN Working Committee on Financial Inclusion (WC-FINC) in collaboration with the World Bank Group. The ASEAN WC-FINC has the responsibility to deliberately and effectively coordinate initiatives to advance financial inclusion in ASEAN countries through close collaboration with relevant Working Committees and Working Groups. The World Bank Group Global Knowledge and Research Hub in Malaysia focuses on sharing Malaysia’s people-centered development expertise and creating new innovative policy research on local, regional, and global issues. It is centered on support for Malaysia’s vision to join the ranks of high-income economies by 2020 through inclusive and sustainable growth and to share its lessons with developing countries. The Hub also carries out cutting- edge development policy research in partnership with local and international research institutions. www.worldbank.org/en/country/malaysia/brief/ global-knowledge-and-research-hub Advancing Digital Financial Inclusion in ASEAN Policy and Regulatory Enablers Acknowledgments The “Advancing Digital Financial Inclusion in ASEAN” report was written on the initiative of the ASEAN Working Committee on Financial Inclusion (WC-FINC). This report is the product of a collaboration between the Association of -

Monthly Summary for the Cabinet for the Month of April, 2021

Ministry of Education Department of Higher Education MONTHLY SUMMARY FOR THE CABINET FOR THE MONTH OF APRIL, 2021: 1. Disruption due to covid pandemic situation & Preventive measures taken to contain its spread. a) Impact on office work in the Ministry and measures taken to prevent it With the second wave of coronavirus, 106 cases have been reported in MoE during March 21 and April 21. Periodic RTPCR tests have been held in Shastri Bhawan and a vaccination camp was organised for the officers/officials of the Ministry on 30th April, 20221. To take measures to prevent its spread, the physical attendance of the officers of the level of Under Secretary or equivalent and below has been restricted to 50% of the actual strength. The officers/staff attending the office, have been asked to follow staggered timings and avoid overcrowding. b) Postponement of all offline examinations scheduled in the month of May, 2021- Instructions have been issued to all Vice Chancellors/Directors of Institutions to postpone all offline examinations scheduled in the month of May, 2021.The Online examinations, etc may however be continued. The decision on further examination will be reviewed in the first week of June,2021. The institutions have been further advised to ensure that immediate support, if needed, should be provided to students at the earliest, to keep them out of any possible distress. All Institutions have to encourage eligible persons to go for vaccination and pursue vaccination drive & ensure that everyone follows COVID -19 appropriate behaviour to remain safe. c) Postponement of various other examinations conducted by National Testing Agency (NTA) • Postponement of Joint Entrance Examination (Main) - April & May 2021 Sessions - which was scheduled to be held from 27 to 30 April 2021 & 24 to 28 May 2021 respectively. -

The Relationship Between Indonesia's Gross Domestic

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INDONESIA’S GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT AND INDONESIA-BRIC EXPORT IMPORT By Giovanni Francis 014200900061 A thesis presented to the Faculty of Economics President University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Bachelor Degree in Economics Major in Management January 2013 THESIS ADVISER RECOMMENDATION LETTER This thesis entitled “THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INDONESIA’S GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT AND INDONESIA-BRIC EXPORT IMPORT” prepared and submitted by Giovanni Francis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor Degree in the Faculty of Economic has been reviewed and found to have satisfied the requirements for a thesis fit to be examined. I therefore recommend this thesis for Oral Defense. Cikarang, Indonesia, 25 January 2013 Acknowledged by, Recommended by, Irfan Habsjah, MBA, CMA Ir. B.M.A.S. Anaconda B., MT., MSM Head of Management Study Program Thesis Advisor i DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that this thesis, entitled “THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INDONESIA GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT AND INDONESIA- BRIC COUNTRIES EXPORT IMPORT” is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, an original piece of work that has not been submitted, either in whole or in part, to another university to obtain a degree. Cikarang, Indonesia, 25 January 2013 Giovanni Francis ii PANEL OF EXAMINERS APPROVAL SHEET The Panel of Examiners declare that the thesis entitled “THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INDONESIA GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT AND INDONESIA-BRIC COUNTRIES EXPORT IMPORT” that was submitted by Giovanni Francis majoring in Management from the Faculty of Economics was assessed and approved to have passed the Oral Examinations on January 2013. Ir. Erny Hutabarat, MBA Chair-Panel of Examiners IGNP Luhur Korsika, BSc, MIB Examiner I Ir. -

Asean Guideline for the Conduct of Bioequivalence Studies

ASEAN GUIDELINE FOR THE CONDUCT OF BIOEQUIVALENCE STUDIES Adopted from the : “ GUIDELINE ON THE INVESTIGATION OF BIOEQUIVALENCE” ( European Medicines Agency,London,20 January 2010,CPMP/EWP/QWP/1401/98 Rev 1) with some adaptation for ASEAN application. Document Control No. Date Final July 2004 (8th PPWG Meeting, Bangkok) Revision 1, Draft 1 June 2011, Singapore Revision 1, Draft 2 July 2012, Bangkok, Thailand Revision 1, Draft 3 May 2013, Bali, Indonesia Revision 1, Draft 4 June 2014, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Revision 1, Draft 4 March 2015 , Vientiane ,Lao PDR _ FINAL 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVESUMMARY....................................................................................... 3 1. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................. 3 1.1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................... 3 1.2 GENERIC MEDICINAL PRODUCTS ........................................................... 3 1.3 OTHER TYPES OF APPLICATION............................................................. 4 2. SCOPE............................................................................................................. 4 3. MAIN GUIDELINE TEXT………………………................................................. 5 3.1 DESIGN, CONDUCT AND EVALUATION OF BIOEQUIVALENCE STUDIES…………………………………………………………………………....... 5 3.1.1 Study design.............................................................................................. 6 3.1.2 Comparator and test product…………………………………....................... -

General Assembly at Its Thirty-First Session

UNi1ED NArlONS Distr. GENERAL GENERAL A/32/1640 i\,UJ, \ 2 September 1911 ASSEMBLY ENGLISH ORIGINAL: ENGLISH/FRENCH/ RUSSIAN/SPATHSH Thirty-second session Item 50 of the provisional agenda* Il1PLEMENTATION OF THE DECLARATION ON THE STRENGTHENING OF INTERNATIONAL SECURITY Non-interference in internal affairs of States ~eport of the Secretary-General CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .. 2 11. REPLIES RECEIVED FROM GOVER~ThmNTS 3 Barbados . ............ 3 Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic 3 German Democratic Republic 'j Greece . 4 Guyana .. 4 Hungary 5 Nadagascar 5 Netherlands 1 Philippines 8 Romania 8 Seychelles . 9 Surinam 9 Union of Soviet Socialist Republics 10 United States of America 10 Venezuela 11 Yugoslavia .. .... 11 Annex. List of documents issued since the consideration of the item by tp~ General Assembly at its thirty-first session .......... •• 15 ·Of A/32/150. 77-16430 / ... A/32/164 English Page 2 I. INTRODUCTION 1. At its 98th plenary meeting, on 14 December 1916, the General Assemoly adopted resolution 31/91 entitled "Non-interference in the internal affairs of States", in which it requested the Secretary-General to invite all Memoer States to express their views on ways oy '~1ich greater respect for the-principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of States could De assured, and to report to the Assemoly at its thirty-second session. 2. Pursuant to that request, the Secretary-General, on 8 Feoruary 1911, addressed a note to the Governments of States Hemoers of the United Nations or memoers of specialized agencies, transmitting the text of resolution 31/91 and askin~ for the information requested in that resolution.