The Science-Fictional Janelle Monáe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Take A'trip' to the Gallery —Page 4

I . & i • 4 « Ehra Hau, bronze modalM In Taa Kwon Do In tha 1988 Olymplca, delivers a aplnning back kick to Jaime Myatic during a regular training exerolaa of the American Taa Kwon Do Academy. Take a'trip' to the gallery —page 4 Vice Pres. 'Top' of shake-up the charts -page 2 —page6 NEWS New title, duties added to academic affairs VP After a restmctimng of upper serving as assistant to the interim Provost. level administration at UTSA, However, when a permanent provost is the position of vice president found, Val verde'sconlractis not expected for academic affairs has been tobe renewed. Valverde's offke was con tacted for more informadon, but no mes renamed and expanded. The sages were returned. new position, provost and vice- Dr. Linda Whitson, vice preskknt for president for academic afTairs, administration and planning, was also VP tor academic alMra and now pravoat until a permanent pn>- aaaiata the Interim provoat. voat la appointed. (of Dr. Valverde). Valvenk demotkm. DeLuna said that the Ttie provost position erjcompasses tiie duties of ttie She has no historical knowledge cm the group does not wish to speak to the media subject, and cannot verify or comment on about dwir plans. When adced why she vice president for academic affairs while increasing itsany artkk addressing the subject of Dr. sakl, "Sdategy, I guess." Valvenk." The provost position encompasses the scope of auttiority. Ttie Provost will serve as acting Dr. James W. Wagener, professor in duties of the vice president for academic tlw division of education and presitknt of affairs whik increasing its scope of au UTSA when Valverde was hired, was thority. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Leon Bridges Black Moth Super Rainbow Melvins

POST MALONE ELEANOR FRIEDBERGER LORD HURON MELVINS LEON BRIDGES BEERBONGS & BENTLEYS REBOUND VIDE NOIR PINKUS ABORTION TECHNICIAN GOOD THING REPUBLIC FRENCHKISS RECORDS REPUBLIC IPECAC RECORDINGS COLUMBIA The world changes so fast that I can barely remember In contrast to her lauded 2016 album New View, Vide Noir was written and recorded over a two Featuring both ongoing Melvins’ bass player Steven Good Thing is the highly-anticipated (to put it lightly) life pre-Malone… But here we are – in the Future!!! – and which she arranged and recorded with her touring years span at Lord Huron’s Los Angeles studio and McDonald (Redd Kross, OFF!) and Butthole Surfers’, follow-up to Grammy nominated R&B singer/composer Post Malone is one of world’s unlikeliest hit-makers. band, Rebound was recorded mostly by Friedberger informal clubhouse, Whispering Pines, and was and occasional Melvins’, bottom ender Jeff Pinkus on Leon Bridges’ breakout 2015 debut Coming Home. Beerbongs & Bentleys is not only the raggedy-ass with assistance from producer Clemens Knieper. The mixed by Dave Fridmann (The Flaming Lips/MGMT). bass, Pinkus Abortion Technician is another notable Good Thing Leon’s takes music in a more modern Texas rapper’s newest album, but “a whole project… resulting collection is an entirely new sound for Eleanor, Singer, songwriter and producer Ben Schneider found tweak in the prolific band’s incredible discography. direction while retaining his renowned style. “I loved also a lifestyle” which, according to a recent Rolling exchanging live instrumentation for programmed drums, inspiration wandering restlessly through his adopted “We’ve never had two bass players,” says guitarist / my experience with Coming Home,” says Bridges. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

Collective Memory and the Constructio

Liljedahl: Recalling the (Afro)Future: Collective Memory and the Constructio RECALLING THE (AFRO)FUTURE: COLLECTIVE MEMORY AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF SUBVERSIVE MEANINGS IN JANELLE MONÁE’S METROPOLIS-SUITES Everywhere, the “street” is considered the ground and guarantee of all reality, a compulsory logic explaining all Black Music, conveniently mishearing antisocial surrealism as social realism. Here sound is unglued from such obligations, until it eludes all social responsibility, thereby accentuating its unreality principle. (Eshun 1998: -41) When we listen to music in a non-live setting, we do so via some form of audio reproduction technology. To most listeners, the significant part about the technology is not the technology itself but the data (music) it stores and reverberates into our ears (Sofia 2000). Most of these listeners have memories tied to their favourite songs (DeNora 2000) but if the music is at the centre of the history of a people, can the songs themselves be seen as a form of recollection? In this paper, I suggest that sound reproduction technology can be read as a storage of memories in the context of Black American popular music. I will turn my attention to the critical potential of Afrofuturist narratives in the field of memory- technology in order to focus on how collective memory is performed as Afrofuturist technology in Black American popular music, specifically in the music of Janelle Monáe. At play in the theoretical backdrop of this article are two key concepts: Signifyin(g) and collective memory, the first of which I will describe in simplified terms, while the latter warrants a more thorough discussion. -

25Th Super Bock Super Rock

25th Super Bock Super Rock New line-up announcement: Janelle Monáe July 20, Super Bock Stage July 18, 19, 20 Herdade do Cabeço da Flauta, Meco - Sesimbra superbocksuperrock.pt | facebook.com/sbsr | instagram.com/superbocksuperrock After the line up confirmations of Lana Del Rey, Cat Power, Charlotte Gainsbourg and Christine and The Queens, there’s another feminine talent on her way to Super Bock Super Rock: the North American Grammy-nominated, singer, songwriter, arranger and producer Janelle Monáe, performs on July 20 at the Super Bock Stage. JANELLE MONÁE Janelle Monáe Robinson was born and raised in Kansas City but soon felt the need to go in search of her dreams and headed out to New York. She enrolled in the American Musical and Dramatic Academy and at the time, her goal was to make musicals. Life ended up givigin Janelle some other possibilities and shortly thereafter, she began to participate in several songs by Outkast, having been invited by Big Boi. She began to appear under the spotlight thanks to her enormous talent, being a multifaceted and very focused artist. She released her first EP in 2007, “Metropolis: Suite I (The Chase)”. These first songs caught the producer Diddy’s eyes (Sean “Puffy” Combs) who soon hired Janelle for his label, Bad BoY Records. Her first Grammy nomination came at this time with the single “Many Moons”. Three years later, in 2010, Monae released her debut album. “The ArchAndroid” was inspired by the German film “Metropolis”, which portrays a futuristic world, a dystopian projection of humanity. The album’s whole concept raised some ethical issues and enriched the songs, these authentic pop pearls, filled with soul and funk. -

Eyez on Me 2PAC – Changes 2PAC - Dear Mama 2PAC - I Ain't Mad at Cha 2PAC Feat

2 UNLIMITED- No Limit 2PAC - All Eyez On Me 2PAC – Changes 2PAC - Dear Mama 2PAC - I Ain't Mad At Cha 2PAC Feat. Dr DRE & ROGER TROUTMAN - California Love 311 - Amber 311 - Beautiful Disaster 311 - Down 3 DOORS DOWN - Away From The Sun 3 DOORS DOWN – Be Like That 3 DOORS DOWN - Behind Those Eyes 3 DOORS DOWN - Dangerous Game 3 DOORS DOWN – Duck An Run 3 DOORS DOWN – Here By Me 3 DOORS DOWN - Here Without You 3 DOORS DOWN - Kryptonite 3 DOORS DOWN - Landing In London 3 DOORS DOWN – Let Me Go 3 DOORS DOWN - Live For Today 3 DOORS DOWN – Loser 3 DOORS DOWN – So I Need You 3 DOORS DOWN – The Better Life 3 DOORS DOWN – The Road I'm On 3 DOORS DOWN - When I'm Gone 4 NON BLONDES - Spaceman 4 NON BLONDES - What's Up 4 NON BLONDES - What's Up ( Acoustative Version ) 4 THE CAUSE - Ain't No Sunshine 4 THE CAUSE - Stand By Me 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Amnesia 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Don't Stop 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER – Good Girls 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Jet Black Heart 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER – Lie To Me 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - She Looks So Perfect 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Teeth 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - What I Like About You 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Youngblood 10CC - Donna 10CC - Dreadlock Holiday 10CC - I'm Mandy ( Fly Me ) 10CC - I'm Mandy Fly Me 10CC - I'm Not In Love 10CC - Life Is A Minestrone 10CC - Rubber Bullets 10CC - The Things We Do For Love 10CC - The Wall Street Shuffle 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Closer To The Edge 30 SECONDS TO MARS - From Yesterday 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Kings and Queens 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Teeth 30 SECONDS TO MARS - The Kill (Bury Me) 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Up In The Air 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Walk On Water 50 CENT - Candy Shop 50 CENT - Disco Inferno 50 CENT - In Da Club 50 CENT - Just A Lil' Bit 50 CENT - Wanksta 50 CENT Feat. -

Agency in the Afrofuturist Ontologies of Erykah Badu and Janelle Monáe

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 330–340 Research Article Nathalie Aghoro* Agency in the Afrofuturist Ontologies of Erykah Badu and Janelle Monáe https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0030 Received May 21, 2018; accepted September 26, 2018 Abstract: This article discusses the visual, textual, and musical aesthetics of selected concept albums (Vinyl/CD) by Afrofuturist musicians Erykah Badu and Janelle Monaé. It explores how the artists design alternate projections of world/subject relations through the development of artistic personas with speculative background narratives and the fictional emplacement of their music within alternate cultural imaginaries. It seeks to establish that both Erykah Badu and Janelle Monáe use the concept album as a platform to constitute their Afrofuturist artistic personas as fluid black female agents who are continuously in the process of becoming, evolving, and changing. They reinscribe instances of othering and exclusion by associating these with science fiction tropes of extraterrestrial, alien lives to express topical sociocultural criticism and promote social change in the context of contemporary U.S. American politics and black diasporic experience. Keywords: conceptual art, Afrofuturism, gender performance, black music, artistic persona We come in peace, but we mean business. (Janelle Monáe) In her Time’s up speech at the Grammys in January 2018, singer, songwriter, and actress Janelle Monáe sends out an assertive message from women to the music industry and the world in general. She repurposes the ambivalent first encounter trope “we come in peace” by turning it into a manifest for a present-day feminist movement. Merging futuristic, utopian ideas with contemporary political concerns pervades Monáe’s public appearances as much as it runs like a thread through her music. -

Narrative Strategies and Music in Visual Albums

Narrative strategies and music in visual albums Lolita Melzer (6032052) Thesis BA Muziekwetenschap MU3V14004 2018-2019, block 4 University of Utrecht Supervisor: dr. Olga Panteleeva Abstract According to E. Ann Kaplan, Andrew Goodwin and Carol Vernallis, music videos usually do not have a narrative, at least not one like in classical Hollywood films. David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson state that such a narrative consists of events that are related by cause and effect and take place in a particular time and place. However, articles about music videos have not adequately addressed a new trend, namely the so called “visual album”. This medium is a combination of film and music video elements. Examples are Beyoncé’s much discussed visual album Lemonade from 2016 and Janelle Monáe’s “emotion picture” Dirty Computer from 2018. These visual albums are called ‘narrative films’ by sites such as The Guardian, Billboard and Vimeo, which raises questions about how narrative works in these media forms, because they include music videos which are usually non-narrative. It also poses the question how music functions with the narrative, as in most Hollywood films the music shifts to the background. By looking at the classical Hollywood narrative strategy and a more common strategy used in music videos, called a thread or motif strategy by Vernallis, I have analysed the two visual albums. After comparing them, it seems that both Lemonade and Dirty Computer make use of the motif strategy, but fail in achieving a fully wrought film narrative. Therefore, a different description to visual albums than ‘narrative film’, could be considered. -

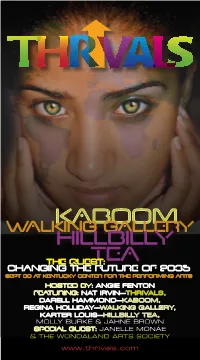

Kaboom Walking Gallery Hillbilly

founder's message KABOOM WALKING GALLERY HILLBILLY THE QUEST:TEA Changing the future of 2035 Sept 30 AT KENTUCKY CENTER FOR THE PerFORMING ARTS HOSTED BY: ANGIE FENTON FEATURING: NAT IRVIN—THRIVALS, DARELL HAMMOND—KABOOM, REGINA HOLLIDAY—WALKING GALLERY, KARTER LOUIS—HILLBILLY TEA, MOLLY BURKE & JAHNE BROWN SPECIAL GUEST: JANELLE MONÁE & THE WONDALAND ARTS SOCIETY www.thrivals.com founder's message Angie Fenton 8:30 WELCOME & OPENING REMARKS Nat Irvin, II, Founder of Thrivals, Woodrow M. Strickler Executive-in-Residence/Professor of Management Practice, College of Business, University of Louisville What if you lived in a city, town, village or slum that didn’t appear on a map? Officially the place you called home didn’t even exist. This was a reality for 14-year-old Salim Shekh and Sikha Patra, who grew up in one of the unchar- tered slums of Kolkata, India, or at least until they decided to do something about it. message Our theme for this year’s Thrivals was inspired by the idea of “positive disruption” as so powerfully from the dean demonstrated by these two young Indian teenagers. Their incredible quest has been documented in the film, The Revolutionary Optimists. Salim and Sikha are positively disrupting the deeply held cultural beliefs that members of their community hold about the future. Instead of the future being consigned to fate and destiny and even luck, Salim and Sikha say that the community’s future will depend on what the members of the community choose to do for themselves. Their message: Forget about fate and luck, and instead do something.