Hikari Kobayashi Paper 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![NOTE: This Paper Was Read at IAML 2010 Moscow, but Lacks Proper Citations and Bibliography. Fully Extended Version Is Scheduled to Be Published in 2011.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5284/note-this-paper-was-read-at-iaml-2010-moscow-but-lacks-proper-citations-and-bibliography-fully-extended-version-is-scheduled-to-be-published-in-2011-115284.webp)

NOTE: This Paper Was Read at IAML 2010 Moscow, but Lacks Proper Citations and Bibliography. Fully Extended Version Is Scheduled to Be Published in 2011.]

[NOTE: This paper was read at IAML 2010 Moscow, but lacks proper citations and bibliography. Fully extended version is scheduled to be published in 2011.] Popular music in Japan: Very different? Not so different? Harumichi YAMADA, Professor, Tokyo Keizai University Tokyo Keizai University, 185-8502, Japan [email protected] Japan has been often referred to as the second largest national market for the popular music business, only after USA. This market has unique aspects in many ways, but the most distinct character is its domestic orientation. While some Asian nations share interests in Japanese popular music for certain degrees, Japanese musicians may hardly be known in the Western world. The language barrier is the largest factor to explain the situation, but it might not be the only reason. Though almost all musical elements in modern Japanese popular music originated in the Western world, they are domesticated or re-organized to produce something quite different from the original Western counterparts. Taking cases from the history of popular music in 20th century Japan, I will describe some typical acclimatizing processes of Western music elements. Introduction of Western music into the schools Japan experienced a rough and rapid process of modernization, or Westernization, in late 19th century, especially after the Meiji Restoration in 1867. The introduction of Western music was one aspect of that modernization. While some elements of Western music like military bands and church hymns arrived a little earlier, their influence was limited. Most ordinary Japanese people were exposed to Western style music through school education, which was under the control of the Ministry of Education. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE , BARBARA ANDRESS: HER CAREER AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO EARLY CHILDHOOD MUSIC EDUCATION A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fuLÉillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By JANETTE DONOVAN HARRIOTT Norman, Oklahoma 1999 ÜMI Number: 9930837 UMI Microform 9930837 Copyright 1999, by UMI Company. -

Western Influence on Japanese Art Song (Kakyoku) in the Meiji Era Japan

WESTERN INFLUENCE ON JAPANESE ART SONG (KAKYOKU) IN THE MEIJI ERA JAPAN JOANNE COLE Master of Music Performance (by Research) Faculty of the Victorian College of the Arts and Music The University of Melbourne December 2013 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Performance (by Research) Produced on Archival Quality Paper Abstract The focus of this dissertation is the investigation of the earliest Western influences on Kōjō no Tsuki (Moon over the Castle) the composition of Japanese composer Rentaro Taki. Kōjō no Tsuki is an example of an early Japanese Art Song known as Kakyoku composed during Meiji Era Japan (1868 - 1912). The dissertation is divided into four chapters with an introduction. Chapter One explores the historical background of the Meiji Era Japan, highlighting the major impact of the signing of the treaty between the United States of America and Japan in 1853. This treaty effectively opened Japan to the West, not only for trade, but for exchange of social, political and cultural ideas. The resulting evolution that occurred in Japan from feudal society to one of early twentieth century is illustrated by reference to articles and writings of the Meiji Era. The second chapter examines the Japanese Art Song form Kakyoku using the example of Rentarō Taki’s song, Kōjō no Tsuki. This chapter presents an argument to illustrate, from an anthropological viewpoint, why this new form of Japanese Art Song could have its own identity based on Western ideas and not be categorised as a Japanese Folk Song known as Minʹyō or Shin Minyō. -

Wind Bands and Cultural Identity in Japanese Schools (Landscapes

Wind Bands and Cultural Identity in Japanese Schools Landscapes: the Arts, Aesthetics, and Education VOLUME 9 SERIES EDITOR Liora Bresler, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, U.S.A. EDITORIAL BOARD Eeva Antilla, Theatre Academy, Helsinki, Finland Magne Espeland, Stord University, Norway Samuel Leong, Hong Kong Institute of Education, Hong Kong Minette Mans, International Consultant, Windhoek, Namibia Gary McPherson, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, U.S.A. Jonothan Neelands, University of Warwick, UK Mike Parsons, The Ohio State University, U.S.A. Shifra Schonmann, University of Haifa, Israel Julian Sefton-Green, University of Nottingham, UK Susan W. Stinson, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, U.S.A. Christine Thompson, Pennsylvania State University, U.S.A. SCOPE This series aims to provide conceptual and empirical research in arts education, (including music, visual arts, drama, dance, media, and poetry), in a variety of areas related to the post-modern paradigm shift. The changing cultural, historical, and political contexts of arts education are recognized to be central to learning, experience, and knowledge. The books in this series present theories and methodological approaches used in arts education research as well as related disciplines - including philosophy, sociology, anthropology and psychology of arts education. For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/6199 David G. Hebert Wind Bands and Cultural Identity in Japanese Schools 13 David G. Hebert, Ph.D. Grieg Academy, Faculty of Education Bergen University College P.O. Box 7030 Nyga˚rdsgaten 112 N-5020 Bergen, Norway [email protected] ISBN 978-94-007-2177-7 e-ISBN 978-94-007-2178-4 DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-2178-4 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2011937238 # Springer Science+Business Media B.V. -

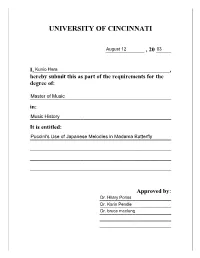

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ PUCCINI’S USE OF JAPANESE MELODIES IN MADAMA BUTTERFLY A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Kunio Hara B.M., University of Cincinnati, 2000 Committee Chair: Dr. Hilary Poriss ABSTRACT One of the more striking aspects of exoticism in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly is the extent to which the composer incorporated Japanese musical material in his score. From the earliest discussion of the work, musicologists have identified many Japanese melodies and musical characteristics that Puccini used in this work. Some have argued that this approach indicates Puccini’s preoccupation with creating an authentic Japanese setting within his opera; others have maintained that Puccini wanted to produce an exotic atmosphere -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Americans at the Leipzig Conservatory (1843–1918) and Their Impact on AJoamnnae Perpipclean Musical Culture Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AMERICANS AT THE LEIPZIG CONSERVATORY (1843–1918) AND THEIR IMPACT ON AMERICAN MUSICAL CULTURE By JOANNA PEPPLE A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 Copyright © 2019 Joanna Pepple Joanna Pepple defended this dissertation on December 14, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: S. Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation George Williamson University Representative Sarah Eyerly Committee Member Iain Quinn Committee Member Denise Von Glahn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii Soli Deo gloria iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so grateful for many professors, mentors, family, and friends who contributed to the success of this dissertation project. Their support had a direct role in motiving me to strive for my best and to finish well. I owe great thanks to the following teachers, scholars, librarians and archivists, family and friends. To my dissertation committee, who helped in shaping my thoughts and challenging me with thoughtful questions: Dr. Eyerly for her encouragement and attention to detail, Dr. Quinn for his insight and parallel research of English students at the Leipzig Conservatory, Dr. -

International Directory of Approved Music Education: Doctoral Dissertations in Progress. INSTITUTION Illinois Univ., Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 310 989 SO 020 229 AUTHOR Colwell, Richard J., Ed.; Dalby, Bruce, Ed. TITLE International Directory of Approved Music Education: Doctoral Dissertations in Progress. INSTITUTION Illinois Univ., Urbana. Council for Research in Music Education. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 1730. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Choral Music; Continuing Education; *Doctoral Dissertations; Elementary Secondary Education; Jazz; Measurement; Music; Musical Instruments; *Music Education; Music Teachers; *Postsecondary Education; Program Development; Psychology; Sociology; Special Education; Teacher Education IDENTIFIERS Ethnomusicology ABSTRACT Three hundred sixty-nine dissertations are listed in this international directory. They are divided into categories (e.g., biographical studies, choral-vocal music, historical studies, string music, etc.), and three indexes are provided: students' names; institutions represented; and subject category. (JB) *********************************************************************** /c Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * from the original document. * ***********************************************************A*********** Directoryc International Music I Dissertation In Progress "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY 1989 idAt ek'(/l P. 2,mpg:hilt) TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES Published by INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." Council for Research in Music Education University of Illinois in behalf of the Graduate -

Bridgewater Review, Vol. 39, No. 1, April 2020

Bridgewater Review Volume 39 Issue 1 Article 1 4-2020 Bridgewater Review, Vol. 39, No. 1, April 2020 Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev Recommended Citation Bridgewater State University. (2020). Bridgewater Review. 39(1). Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/ br_rev/vol39/iss1/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Bridgewater Review Ridged Pots: A Studio Investigation by R. PRESTON SAUNDERS Also in this issue: XIAOYING JING and ON SABBATICAL PAULA BISHOP BIN ZHANG Reflections by LISA LITTERIO, on Felice Bryant’s Country Music on Chinese Family Kinship DIANA FOX, and Songwriting and Ancestor Worship MAURA ROSENTHAL SAMUEL SERNA SIMuRing: Making an Book Reviews by OTÁLVARO Interdisciplinary Project Work HALINA ADAMS, and on Scientists and Public Policy by CHRISTINE BRANDON, JESSICA BIRTHISEL POLINA SABININ, and CHARLES C. COX III NICOLE GLEN, and on Shuji Isawa JENNIE AIZENMAN Poetry by JOE LACROIX AprilVolume 2020 39, Number 1 April 2020 BRIDGEWATER STATE UNIVERSITY1 A Note on COVID-19: The editors of Bridgewater Review hope that all members of our BSU community and their loved ones are safe and well during this crisis. We would like to thank our administrators for providing leadership and guidance; our faculty and librarians for their hard work in moving and teaching courses online; our staff for keeping university business running and supporting us all; and our students for their patience and endurance during a challenging time. “Do you Remember? When you got to school LATE and the Chalk trays weren’t dusted __” (Hilda M. -

Content Analysis of the Journal of Historical Research in Music Education: 1980-2019

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1-1-2019 Content Analysis Of The Journal Of Historical Research In Music Education: 1980-2019 Gail Simpson Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Music Education Commons Recommended Citation Simpson, Gail, "Content Analysis Of The Journal Of Historical Research In Music Education: 1980-2019" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1944. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1944 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTENT ANALYSIS OF THE JOURNAL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH IN MUSIC EDUCATION: 1980 – 2019 A Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music University of Mississippi by Gail A. Simpson December 2019 Copyright Gail A. Simpson 2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The purpose of this descriptive study is to explore the trends in historical research over a period of forty years (1980-2019) as presented in peer-reviewed Journal of Historical Research in Music Education (JHRME). This content analysis is geared towards examining categories of research conducted particularly within the last decade (2010-2019) with comparisons to previous studies. Adopting categories and definitions from Heller (1985), McCarthy (1999, 2012), and Stabler (1986), five questions guide the focus of investigation to include historical periods of study (e.g., 20th century), individuals, events, outcomes, and process variables, i.e., the teacher, the learner, the interaction of the teacher and the learner, the content of instruction, and the environment of instruction. -

The Cultural Relevance of Music Education As It Relates to African American Students in South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2020 The Cultural Relevance of Music Education as it relates to African American Students in South Carolina Felicia Denise Denise Myers Bulgozdy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Recommended Citation Bulgozdy, F. D.(2020). The Cultural Relevance of Music Education as it relates to African American Students in South Carolina. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/ 5849 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Cultural Relevance of Music Education as it relates to African American Students in South Carolina by Felicia Denise Myers Bulgozdy Bachelor of Music University of South Carolina, 2007 Master of Education Columbia College, 2010 _______________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Education in Curriculum and Instruction College of Education University of South Carolina 2020 Accepted by: Rhonda Jeffries, Major Professor James Kirylo, Committee Member Terrance McAdoo, Committee Member Peter Duffy, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Felicia Denise Myers Bulgozdy, 2020 All Rights Reserved. ii Dedication For my parents, William and Mary, and my husband Rob. I love and appreciate you more than you will ever know. “Every good thing I have done, Everything that I've become, Everything that's turned out right, Is because you're in my life. -

N: 5114;090:1353“ :.\: Pltblic

e" N:‘ a 5114;090:1353“ :.\: PLTBLIC SCI-iCOL ,‘vELS'C : 1 YR F; cr ‘re gxegree {J M. .xA- H: -. 'Ir\ -. - ‘- 'xrg' ,5 "I ‘1 (\‘- x 7“ 1“” l I}_§! ‘uxr‘\ fix‘.«.1h7‘4\’.kL—lg UL“. "..i_ -V‘I:h‘.-' \vfi.” LEAF—dd yu‘: VLL-h I ’\ [‘1 Ik# fl 0 . .K a." .r" 1 yaw... :.r/!..lln NIP. 1...»..5 METHODOLOGY IN PUBLIC SCHOOL MUSIC A Survey of Changes in the Aims and Procedures of Music Teaching in the Public Schools of the United States During the Past One Hundred Years. by Wenda Virginia £39k A THESIS Submitted to the Graduate School of Michigan State College of Agriculture and Applied Science in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music July, 1939 IHESIS TABLE OF CONTENTS *%*** Introduction . 1 I. The Beginning of Music Education . 3 II. Hethods in Early School Music . 9 III. The Influence of Luther Whiting Mason . .13 IV. The Attempt to Solve the Reading Problem . .18 V. The "New Education" in Music. .24 VI. Widening Horizons . .31 (a) Elementary Music . .31 (b) Junior High School Music . .36 (c) Senior High School Music . .44 VIII.Recent Practices and Tendencies . .55 IX. Summary . .62 Bibliograpm O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O .66 ,FV73rnh ?°. - a a J J--“:’. *‘ xi)". 1} ’ INTRODUCTION *** During the century since the introduction of public school music, the educational system of the United States has grown from the one room district school, with its emphasis upon routine and for- mal drill, to a highly complex, many-sided system. -

Wotnen Ami Western Mrlsic in Hpntz: 1865 to the Present

University of Alberta Four Recitals and an Essay: Wotnen ami Western Mrlsic in hpntz: 1865 to the Present Teruka Nishikawa A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the desree of Doctor of Music. Department of Music Edmonton, Alberta FaII 2000 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, nie Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Yow lS/e Votre dlennce The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Librq of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, ioan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfoxm, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/^, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract One of ten hears about the international success of classicd musicians from Japan. However, it has only been less than one hundred and fifty years since western art music was introduced to the country. With some debt to the recent ferninist studies in musicoIogy, female composers have appeared from the shadows of great male composers.