Home-Range Size and Activity of the Red-Footed Tortoise, Chelonoidis Carbonarius (Spix, 1824) in a Brazilian Coastal Shrub Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

§4-71-6.5 LIST of CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November

§4-71-6.5 LIST OF CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November 28, 2006 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Plesiopora FAMILY Tubificidae Tubifex (all species in genus) worm, tubifex PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Crustacea ORDER Anostraca FAMILY Artemiidae Artemia (all species in genus) shrimp, brine ORDER Cladocera FAMILY Daphnidae Daphnia (all species in genus) flea, water ORDER Decapoda FAMILY Atelecyclidae Erimacrus isenbeckii crab, horsehair FAMILY Cancridae Cancer antennarius crab, California rock Cancer anthonyi crab, yellowstone Cancer borealis crab, Jonah Cancer magister crab, dungeness Cancer productus crab, rock (red) FAMILY Geryonidae Geryon affinis crab, golden FAMILY Lithodidae Paralithodes camtschatica crab, Alaskan king FAMILY Majidae Chionocetes bairdi crab, snow Chionocetes opilio crab, snow 1 CONDITIONAL ANIMAL LIST §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Chionocetes tanneri crab, snow FAMILY Nephropidae Homarus (all species in genus) lobster, true FAMILY Palaemonidae Macrobrachium lar shrimp, freshwater Macrobrachium rosenbergi prawn, giant long-legged FAMILY Palinuridae Jasus (all species in genus) crayfish, saltwater; lobster Panulirus argus lobster, Atlantic spiny Panulirus longipes femoristriga crayfish, saltwater Panulirus pencillatus lobster, spiny FAMILY Portunidae Callinectes sapidus crab, blue Scylla serrata crab, Samoan; serrate, swimming FAMILY Raninidae Ranina ranina crab, spanner; red frog, Hawaiian CLASS Insecta ORDER Coleoptera FAMILY Tenebrionidae Tenebrio molitor mealworm, -

Texas Tortoise

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THE TEXAS TORTOISE, CONTACT: ∙ TPWD: 800-792-1112 OF THE FOUR SPECIES OF TORTOISES FOUND http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/ IN NORTH AMERICA, THE TEXAS TORTOISE TEXAS ∙ Gulf Coast Turtle and Tortoise Society: IS THE ONLY ONE FOUND IN TEXAS. 866-994-2887 http://www.gctts.org/ THE TEXAS TORTOISE CAN BE FOUND IF YOU FIND A TEXAS TORTOISE THROUGHOUT SOUTHERN TEXAS AS WELL AS (OUT OF HABITAT), CONTACT: TORTOISE ∙ TPWD Law Enforcement TORTOISE NORTHEASTERN MEXICO. ∙ Permitted rehabbers in your area http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/huntwild/wild/rehab/ GOPHERUS BERLANDIERI UNFORTUNATELY EVERYTHING THERE ARE MANY THREATS YOU NEED TO KNOW TO THE SURVIVAL OF THE ABOUT THE STATE’S ONLY TEXAS TORTOISE: NATIVE TORTOISE HABITAT LOSS | ILLEGAL COLLECTION & THE THREATS IT FACES ROADSIDE MORTALITIES | PREDATION EXOTIC PATHOGENS TexasTortoise_brochure_V3.indd 1 3/28/12 12:12 PM COUNTIES WHERE THE TEXAS TORTOISE IS LISTED THE TEXAS TORTOISE (Gopherus berlandieri) is the smallest of the North American tortoises, reaching a shell length of about TEXAS TORTOISE AS A THREATENED SPECIES 8½ inches (22cm). The Texas tortoise can be distinguished CAN BE FOUND IN THE STATE OF TEXAS AND THEREFORE from other turtles found in Texas by its cylindrical and IS PROTECTED BY STATE LAW. columnar hind legs and by the yellow-orange scutes (plates) on its carapace (upper shell). IT IS ILLEGAL TO COLLECT, POSSESS, OR HARM A TEXAS TORTOISE. PENALTIES CAN INCLUDE PAYING A FINE OF Aransas, Atascosa, Bee, Bexar, Brewster, $273.50 PER TORTOISE. Brooks, Calhoun, Cameron, De Witt, Dimmit, Duval, Edwards, Frio, Goliad, Gonzales, Guadalupe, Hidalgo, Jackson, Jim Hogg, Jim Wells, Karnes, Kenedy, Kinney, Kleberg, La Salle, Lavaca, Live Oak, Matagorda, Maverick, McMullen, Medina, Nueces, WHAT SHOULD YOU Refugio, San Patricio, Starr, Sutton, Terrell, Uvalde, Val Verde, Victoria, Webb, Willacy, DO IF YOU FIND A Wilson, Zapata, Zavala TEXAS TORTOISE? THE TEXAS TORTOISE IS THE SMALLEST IN THE WILD AN INDIVIDUAL TEXAS TORTOISE LEAVE IT ALONE. -

Egyptian Tortoise (Testudo Kleinmanni)

EAZA Reptile Taxon Advisory Group Best Practice Guidelines for the Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) First edition, May 2019 Editors: Mark de Boer, Lotte Jansen & Job Stumpel EAZA Reptile TAG chair: Ivan Rehak, Prague Zoo. EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (May 2019) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA Reptile TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. EAZA Preamble Right from the very beginning it has been the concern of EAZA and the EEPs to encourage and promote the highest possible standards for husbandry of zoo and aquarium animals. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

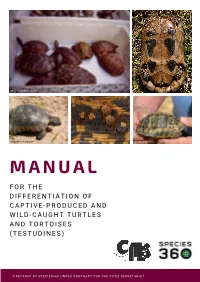

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

University of Nevada, Reno Effects of Fire on Desert Tortoise (Gopherus Agassizii) Thermal Ecology a Dissertation Submitted in P

University of Nevada, Reno Effects of fire on desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) thermal ecology A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology by Sarah J. Snyder Dr. C. Richard Tracy/Dissertation Advisor May 2014 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by SARAH J. SNYDER Entitled Effects of fire on desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) thermal ecology be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY C. Richard Tracy, Ph.D., Advisor Kenneth Nussear, Ph.D., Committee Member Peter Weisberg, Ph.D., Committee Member Lynn Zimmerman, Ph.D., Committee Member Lesley DeFalco, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph. D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2014 i ABSTRACT Among the many threats facing the desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) is the destruction and alteration of habitat. In recent years, wildfires have burned extensive portions of tortoise habitat in the Mojave Desert, leaving burned landscapes that are virtually devoid of living vegetation. Here, we investigated the effects of fire on the thermal ecology of the desert tortoise by quantifying the thermal quality of above- and below-ground habitat, determining which shrub species are most thermally valuable for tortoises including which shrub species are used by tortoises most frequently, and comparing the body temperature of tortoises in burned and unburned habitat. To address these questions we placed operative temperature models in microhabitats that received filtered radiation to test the validity of assuming that the interaction between radiation and radiation-absorbing properties of the model can result in a single, mean radiant absorptance regardless of whether the incident solar radiation is direct unfiltered or filtered by plant canopies, using the desert tortoise as a case study. -

Indian Star Tortoise Care

RVC Exotics Service Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street London NW1 0TU T: 0207 554 3528 F: 0207 388 8124 www.rvc.ac.uk/BSAH INDIAN STAR TORTOISE CARE Indian star tortoises originate from the semi-arid dry grasslands of Indian subcontinent. They can be easily recognised by the distinctive star pattern on their bumpy carapace. Star tortoises are very sensitive to their environmental conditions and so not recommended for novice tortoise owners. It is important to note that these tortoises do not hibernate. HOUSING • Tortoises make poor vivarium subjects. Ideally a floor pen or tortoise table should be created. This needs to have solid sides (1 foot high) for most tortoises. Many are made out of wood or plastic. A large an area as possible should be provided, but as the size increases extra basking sites will need to be provided. For a small juvenile at least 90 cm (3 feet) long x 30 cm (1 foot) wide is recommended. This is required to enable a thermal gradient to be created along the length of the tank (hot to cold). • Hides are required to provide some security. Artificial plants, cardboard boxes, plant pots, logs or commercially available hides can be used. They should be placed both at the warm and cooler ends of the tank. • Substrates suitable for housing tortoises include newspaper, Astroturf, and some of the commercially available substrates. Natural substrate such as soil may also be used to allow for digging. It is important that the substrates either cannot be eaten, or if they are, do not cause blockages as this can prove fatal. -

Aldabrachelys Arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold's Giant Tortoise

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectTestudinidae of the IUCN/SSC — AldabrachelysTortoise and Freshwater arnoldi Turtle Specialist Group 028.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.028.arnoldi.v1.2009 © 2009 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 18 October 2009 Aldabrachelys arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold’s Giant Tortoise JUSTIN GERLACH 1 1133 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge CB1 7BX, United Kingdom [[email protected]] SUMMARY . – Arnold’s giant tortoise, Aldabrachelys arnoldi (= Dipsochelys arnoldi) (Family Testudinidae), from the granitic Seychelles, is a controversial species possibly distinct from the Aldabra giant tortoise, A. gigantea (= D. dussumieri of some authors). The species is a morphologi- cally distinctive morphotype, but has so far not been genetically distinguishable from the Aldabra tortoise, and is considered synonymous with that species by many researchers. Captive reared juveniles suggest that there may be a genetic basis for the morphotype and more detailed genetic work is needed to elucidate these relationships. The species is the only living saddle-backed tortoise in the Seychelles islands. It was apparently extirpated from the wild in the 1800s and believed to be extinct until recently purportedly rediscovered in captivity. The current population of this morphotype is 23 adults, including 18 captive adult males on Mahé Island, 5 adults recently in- troduced to Silhouette Island, and one free-ranging female on Cousine Island. Successful captive breeding has produced 138 juveniles to date. -

(Geochelone Pardalis) on Farmland in the Nama-Karoo

THE STATUS AND ECOLOGY OF THE LEOPARD TORTOISE (GEOCHELONE PARDALIS) ON FARMLAND IN THE NAMA-KAROO MEGAN KAY McMASTER Submitted in fulfilment ofthe academic requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE School ofBotany and Zoology University ofNatal Pieterrnaritzburg March 2001 Preface The experimental work described in this dissertation was carried out in the School of Botany and Zoology, University ofNatal, Pietermaritzburg, from November 1997 to March 2001, under the supervision ofDr. Colleen T. Downs. This study is the original work ofthe author and has not been submitted in any form for any diploma or degree to another university. Where use has been made ofthe work of others, it is duly acknowledged in the text. Each chapter is written in the format ofthe journal it has been submitted to. ..fj~K'. Megan Kay McMaster Pietermaritzburg March 2001 11 This thesis is dedicated to myfather, the late Eric Ralph McMaster, for his constant encouragement and beliefin me, and to my brother, the late Gregory CIifton McMaster,for always making me smile. III Abstract The Family Testudinidae (Suborder Cryptodira) is represented by 40 species worldwide and reaches its greatest diversity in southern Africa, where 14 species occur (33%), ten of which are endemic to the subcontinent. Despite the strong representation ofterrestrial tortoise species in southern Africa, and the importance ofthe Karoo as a centre of endemism ofthese tortoise species, there is a paucity ofecological information for most tortoise species in South Africa. With chelonians being protected in < 15% ofall southern African reserves it is necessary to find out more about the ecological requirements, status, population dynamics and threats faced by South African tortoise species to enable the formulation ofeffective conservation measures. -

Keeping and Breeding Leopard Tortoises (Geochelone Pardalis)

Keeping and breeding Leopard Tortoises Keeping and breeding Leopard Tortoises (Geochelone pardalis). Part 1. Egg-laying, incubation, and care of hatchlings ROBERT BUSTARD HIS captive-breeding/husbandry article on a length of about 15cm (6"). At this time they will Tvery beautiful — indeed magnificent-looking court females assiduously. Females are — tortoise, resulted from a discussion at Council considerably larger, however, before they in October 2001 on the inadequate number of commence breeding with the result that these practical articles on keeping the various species of newly sexually mature males have trouble in reptiles and amphibians being submitted to The mounting them successfully. Although female Herpetological Bulletin. I at once had a `whip leopards take on average a couple of years longer round' getting everyone present to undertake to than males to reach sexual maturity, size/weight is write an article on some topic of their competence. always a much more reliable guide than age in I then asked Council what they wanted me to reptiles and females can be expected to commence write. I think it was Barry Pomfret who actually breeding around a weight of 8kg. `roped me in' for this topic as he said there were a Because of the leopards' highly-domed lot of people keeping 'leopards' these days. Partly carapace males need to be sufficiently large to be I was to blame, as I had said that they were able to successfully mount any given female. `boring', and didn't do much and — insult of Enthusiasm is not enough! As is common in insults — that one would be as good with some tortoises, optimistic males will usually select the garden gnome leopards as with the real thing! largest female on offer. -

ECUADOR – Galapagos Giant Tortoises Stolen From

CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA NOTIFICATION TO THE PARTIES No. 2018/076 Geneva, 30 October 2018 CONCERNING: ECUADOR Galapagos giant tortoises stolen from breeding center 1. This Notification is being published at the request of Ecuador. 2. The CITES Management Authority of Ecuador informed the Secretariat that on 27 September 2018, the Galapagos National Park Directorate filed a criminal complaint in Ecuador following the theft of 123 live Galapagos giant tortoises (Chelonoidis niger) from the Galapagos National Park breeding center on Isabela Island. 3. The Galapagos giant tortoise (Chelonoidis niger1) is included in CITES Appendix I. 4. The stolen tortoises range from one to six years in age. One-year-old Galapagos giant tortoises may be around six centimetres in carapace length and weigh an estimated 200 grams. A six-year-old Galapagos giant tortoise could range from 12 to 30 centimetres in carapace length, and weigh around two kilograms. 5. The likely market for the stolen specimens is outside of Ecuador, and the CITES Management Authority of Ecuador therefore requests that the present Notification be distributed as widely as possible among police, customs and wildlife enforcement authorities. 6. Parties are requested to inform the CITES Management Authority of Ecuador should any permits or certificates regarding trade in these specimens be received. The Management Authority of Ecuador also requests that CITES Management Authorities do not approve any export, import or re-export permit applications related to this species before consulting with the CITES Management Authority of Ecuador. 7. Parties that seize illegally traded specimens of Chelonoidis niger are also requested to communicate information about these seizures to the Management Authority of Ecuador.