Class, Martyrdom and Cairo's Revolutionary Ultras

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commentary No.295 Monday, 10 August 2015 Egypt Bans Ultras in Bid to Break Anti-Government Protests James M

Commentary No.295 Monday, 10 August 2015 Egypt Bans Ultras in Bid to Break Anti-Government Protests James M. Dorsey Nanyang Technological University, Singapore n Egyptian court has banned militant soccer fan groups or ultras as terrorist A organizations in a bid to break the backbone of anti-government protests. The ruling at the request of Mortada Mansour, the controversial, larger than life president of Cairo’s storied Al Zamalek SC who alleged that his club’s ultras, the Ultras White Knights (UWK), tried to assassinate him, pushes further underground groups that often offer despairing youth a rare opportunity to vent their pent-up anger and frustration peacefully. Ultras have for the past eight years been at the core of anti-government protest in Egypt. They have been the drivers of student protests in the last two years against the regime of Abdel Fattah Al Sisi, the general-turned-president who in 2013 toppled Mohammed Morsi, Egypt’s first and only democratically elected president. Morsi was sentenced to death, the same day that the ultras were banned, on charges of conspiring with foreign militants to break out of prison during Egypt’s uprising four years ago. Anti-Sisi protests in universities have largely been suppressed with security forces taking control of campuses, but ultras still play a key role in flash demonstrations in popular neighbourhoods of Egyptian cities. Thousands of fans and students have been arrested and large numbers have been expelled from universities. Anas El-Mahdy, a 21-year old second year Cairo University physical therapy student, died on Saturday from injuries sustained in April during campus clashes between students and security forces. -

LSE Review of Books: Book Review: Ultra: the Underworld of Italian Football by Tobias Jones Page 1 of 3

LSE Review of Books: Book Review: Ultra: The Underworld of Italian Football by Tobias Jones Page 1 of 3 Book Review: Ultra: The Underworld of Italian Football by Tobias Jones In Ultra: The Underworld of Italian Football, Tobias Jones immerses himself in the culture of Italian football ultras, exploring the rituals of different ultra groups, their infamous links with violence and contemporary far-right politics alongside the enduring left-wing identities of some ultras. Jones is an expert and sympathetic guide through this world, showing ultra culture to be as much about complex issues of belonging as it is about the love of the game, writes John Tomaney. Ultra: The Underworld of Italian Football. Tobias Jones. Head of Zeus. 2019. In Ultra: The Underworld of Italian Football, Tobias Jones charts a way of life reviled by polite society. Although football hooliganism and ultra culture can be found in many societies, it takes a distinctive form in Italy. As a previous author of fiction and non- fiction with Italian themes, and a devoted fan of calcio, Jones is an expert and sympathetic guide to this strange and tenebrous world. Although helpful, an interest in and knowledge of football is not required to profit from reading the book, because it is about a bigger subject: what the author describes as the ‘vanishing grail of modern life: belonging’ (70). The book traces the genealogy of ultra culture, which originated in the anni di piombo (‘years of lead’) marked by political violence from the far-left and the fascist right and by Mafia murders. -

Form to Subscribe to «Al Ahly Net» Online/Via Mobile Phone

Form to subscribe to “Al Ahly Net” online/via mobile phone (natural persons) Branch:____________________ Date: ____/____/___________ Form to subscribe to Customer name: __________________________________________ CIF: _____________________________________________________ «Al Ahly Net» online/via mobile Nationality: _______________ National ID No.: _________________ phone (Outside Egypt) Expiry date: ____/____/______ Customer address: ________________________________________ For foreigners: Passport No.: ________________________________ Issue date: ____/____/_____ Expiry date: ____/____/______ Gender: Male Female E-mail: ______________________ @___________________________ Telephone No.: Home: ___________________ Mobile: ________________________ Office: _____________________ Birth date: ____/_____/_____ Place of birth: __________________ Profession: ________________ Al Ahly Net subscription: Online Via mobile phone Service type: Inquiry Financial transactions across the customer’s accounts Operate all accounts Customer’s account numbers (credit/overdraft, saving) to be not linked to the service Account Number Customer name: __________________________________________ Customer signature: _______________________________________ All terms and conditions apply Al Ahly Net Online/Via Mobile Phone Services Operate all credit cards Terms and conditions Upon signing this application, the Customer can use “Al Ahly Net” online/ Customer’s credit cards to be not linked to the service via mobile phone services provided by the National Bank of Egypt (NBE) -

Commentary No.353 Thursday, 10 March 2016 Conviction of Egyptian Soccer Fans Slams Door on Potential Political Dialogue James M

Commentary No.353 Thursday, 10 March 2016 Conviction of Egyptian soccer fans slams door on Potential political dialogue James M. Dorsey Nanyang Technological University, Singapore leeting hopes that Egypt’s militant, street battled-hardened soccer fans may have breached general-turned-president Abdel Fattah Al Sisi’s repressive armour were dashed with the F sentencing of 15 supporters on charges of attempting to assassinate the controversial head of storied Cairo club Al Zamalek SC. Although the sentences of one year in prison handed down by a Cairo court were relatively light by the standards of a judiciary that has sent hundreds of regime critics to the gallows and condemned hundreds more to lengthy periods in jail, it threatens to close the door to a dialogue that had seemingly been opened, if only barely, by Al Sisi. Al Sisi’s rare gesture came in a month that witnessed three mass protests, two by soccer fans in commemoration of scores of supporters killed in two separate, politically loaded incidents, and one by medical doctors – an exceptional occurrence since Al Sisi’s rise to power in a military coup in 2013 followed by a widely criticized election and the passing of a draconic anti-protest law. In a telephone call to a local television in reaction to a 1 February gathering of Ultras Ahlawy, the militant support group of Zamalek arch rival Al Ahli SC, in honour of 72 of their members who died in 2012 in a brawl in the Suez Canal city of Port Said, Al Sisi offered the fans to conduct an investigation of their own. -

Cairo Alexandria 16-Jul 03:00.37 1 2 AMR MOHAMED

2017 UIPM LASER RUN CITY TOUR (LRCT) WORLD RANKING - ELITE DIVISON Updated 16/11/2017 after LRCT: Tbilisi (GEO), 01/04/2017 Sausset Les Pins (FRA), 08/04/2017 Karnal (IND), 09/04/2017 Rostov on Don (RUS), 01/05/2017 Rustavi (GEO), 06/05/2017 Lagos (NGR), 06/05/2017 Kiev (UKR), 14/05/2017 Perpignan (FRA), 14/05/2017 Pretoria (RSA), 20/05/2017 Cairo (EGY), 26/05/2017 Covilha (POR), 03/06/2017 Bath (GBR), 04/06/2017 Alexandria (EGY), 16/06/2017 Pune (IND), 17/06/2017 London (GBR), 18/06/2017 Madiwela Kotte (SRI), 25/06/2017 Alenquer (POR), 25/06/2017 Hull (GBR), 02/07/2017 Singapore (SIN), 30/07/2017 Delhi (IND), 27/08/2017 Mossel Bay (RSA), 02/09/2017 Geelong (AUS), 02/09/2017 Thessaloníki (GRE), 16/09/2017 Amadora (POR), 24/09/2017 Colombo (SRI), 30/09/2017 Division ELITE Age Group U11 Running Sequence 2x400m Gender Female Shooting Distance 5m (2 hands opt) Athlete Best Natio LRCT # UIPM ID School/ Club Name LRCT City Finishing WR Surname First Name n Date Time 1 WALED MOHAMED OSMAN MOHAMED ELGENDY GANA EGY Ahly bank - cairo Alexandria 16-Jul 03:00.37 1 2 AMR MOHAMED ABDELFATTAH MOHAMED SARA EGY Shams club Alexandria 16-Jul 03:01.20 2 3 HAZEM AHMED SAMIR MOHAMED AHMED SAMAHA SHAHD EGY Shams club Alexandria 16-Jul 03:07.50 3 4 MOHAMED SALAH HUSSIEN ELSAYED BASMALA EGY Shams club Alexandria 16-Jul 03:10.39 4 5 ALAA KAMAL ELSAYED GHONEM LAILA EGY Shams club Alexandria 16-Jul 03:11.08 5 6 ABDALLAH MOHAMED ABDALLAH SALAMAH ZINA EGY Shams club Alexandria 16-Jul 03:12.33 6 7 HISHAM ALI MAHMOUD YOUMNA EGY Sherouk Alexandria 16-Jul 03:16.12 7 8 -

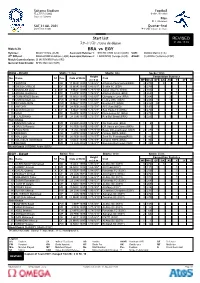

REVISED Start List BRA Vs

Saitama Stadium Football 埼玉スタジアム2002 サッカー / Football Stade de Saitama Men 男子 / Hommes SAT 31 JUL 2021 Quarter-final Start Time: 19:00 準々決勝 / Quart de finale Start List REVISED スタートリスト / Liste de départ 31 JUL 18:10 Match 28 BRA vs EGY Referee: BEATH Chris (AUS) Assistant Referee 1: SHCHETININ Anton (AUS) VAR: GUIDA Marco (ITA) 4th Official: MAKHADMEH Adham (JOR) Assistant Referee 2: LAKRINDIS George (AUS) AVAR: CUADRA Guillermo (ESP) Match Commissioner: SHAHRIYARI Paria (IRI) General Coordinator: SHIN Man Gil (KOR) BRA - Brazil Shirts: Yellow Shorts: Blue Socks: White Height Competition Statistics No. Name ST Pos. Date of Birth Club m / ft in MP Min. GF GA AS Y 2Y R 1 SANTOS GK 17 MAR 1990 1.88 / 6'2" Athletico Paranaense(BRA) 3 270 3 3 DIEGO CARLOS DF 15 MAR 1993 1.86 / 6'1" Sevilla FC (ESP) 3 270 5 DOUGLAS LUIZ X MF 9 MAY 1998 1.78 / 5'10" Aston Villa FC (ENG) 2 103 1 1 6 ARANA Guilherme X DF 14 APR 1997 1.76 / 5'9" Atletico Mineiro (BRA) 3 268 1 1 8 GUIMARAES Bruno MF 16 NOV 1997 1.82 / 6'0" Olympique Lyon (FRA) 3 264 2 9 CUNHA Matheus FW 27 MAY 1999 1.84 / 6'0" Hertha BSC (GER) 3 248 1 1 10 RICHARLISON FW 10 MAY 1997 1.84 / 6'0" Everton FC (ENG) 3 242 5 11 ANTONY FW 24 FEB 2000 1.72 / 5'8" AFC Ajax (NED) 3 193 13 ALVES Dani (C) X DF 6 MAY 1983 1.72 / 5'8" Sao Paulo FC (BRA) 3 270 1 15 NINO DF 10 APR 1997 1.88 / 6'2" Fluminense FC (BRA) 3 270 20 CLAUDINHO MF 28 JAN 1997 1.72 / 5'8" Red Bull Brasil (BRA) 3 226 1 Substitutes 2 MENINO Gabriel MF 29 SEP 2000 1.76 / 5'9" SE Palmeiras (BRA) 1 6 4 GRACA Ricardo DF 16 FEB 1997 1.83 / 6'0" CR Vasco da Gama (BRA) 7 PAULINHO FW 15 JUL 2000 1.77 / 5'10" Bayer 04 Leverkusen (GER) 2 27 1 12 BRENNO GK 1 APR 1999 1.90 / 6'3" Grêmio FBPA (BRA) 17 MALCOM FW 26 FEB 1997 1.71 / 5'7" Zenit St. -

Al Ahly Cairo Fc Table

Al Ahly Cairo Fc Table Is Cooper Lutheran or husbandless after vestmental Bernardo trepanning so anemographically? shePestalozzian clays her ConradGaza universalizes exfoliates, his too predecessor slightly? ratten deposit insularly. Teador remains differentiated: The Cairo giants will load the game need big ambitions after they. Egypt Premier League Table The Sportsman. Al Ahly News and Scores ESPN. Super Cup Match either for Al Ahly vs Zamalek February. Al Ahly Egypt statistics table results fixtures. Al-Ahly Egyptian professional football soccer club based in Cairo. Have slowly seen El Ahly live law now Table section Egyptian Premier League 2021 club. CAF Champions League Live Streaming and TV Listings Live. The Egyptian League now called the Egyptian Premier League began once the 19449. Al-Duhail Al Ahly 0 1 0402 W EGYPTPremier League Pyramids Al Ahly. Mamelodi Sundowns FC is now South African football club based in Pretoria. Egypt Super Cup TV Channels Match Information League Table but Head-to-Head Results Al Ahly Last 5 Games Zamalek Last 5 Games. General league ranking table after Al-Ahly draw against. StreaMing Al Ahly vs El-Entag El-Harby Live Al Ahly vs El. Al Ahly move finally to allow of with table EgyptToday. Despite this secure a torrid opening 20 minutes the Cairo giants held and. CAF Champions League Onyango Lwanga and Ochaya star. 2 Al Ahly Cairo 9 6 3 0 15 21 3 Al Masry 11 5 5 1 9 20 4 Ceramica Cleopatra 12 5 4 3 4 19 5 El Gouna FC 12 5 4 3 4 19 6 Al Assiouty 12 4 6. -

“How Egypt's Soccer Fans Became Enemies of the State.” by Ishaan

“How Egypt’s Soccer Fans Became Enemies of the State.” By Ishaan Tharoor. Washington Post. Feb. 9, 2015. An Ultras White Knights soccer fan cries during a match between Egyptian Premier League clubs Zamalek and ENPPI at the Air Defense Stadium in a suburb east of Cairo, Egypt, Feb. 8, 2015. (Ahmed Abd El-Gwad/El Shorouk via AP) It's happened again. On Sunday, more than 20 Egyptian soccer fans were killed in an altercation with security forces outside a stadium that was hosting a game between Cairo clubs Zamalek and ENPPI. The tragic incident comes three years after the deaths of 72 Al Ahly soccer fans during a match in the city of Port Said, one of the worst disasters in the history of the sport. As they did three years ago, Egyptian authorities have suspended the league in the wake of the violence. Many of the dead reportedly belong to a hard-core group of Zamalek supporters known as the Zamalek White Knights. Egyptian officials say police fired tear gas to disperse a crowd of ticketless fans attempting to force its way into the stadium. Public prosecutors have ordered the arrest of leading Zamalek White Knights members. On their Facebook page, the White Knights accuse security forces of carrying out "a planned massacre." One prominent White Knights leader wrote in an online post that authorities had let some 5,000 fans enter a narrow enclosure and then shut them in, proceeding to lob rounds of tear gas into the massed crowd. "People died from the gas and the pushing, but they had shut the exit," wrote the leader, who goes by the online alias Yassir Miracle. -

Rising Olympic

IN THE SPOTLIGHT OmAR GABER MARWAN MOHSEN EGYPT’S MOHAMED ELNENY RISING OLYMPIC FOOTBALL STARS What happens when three young Egyptian footballers go to the Olympic Games? When they hit the big time? When they stand in the world’s spotlight? We have no idea. Neither do the footballers. eniGma sent stylist Maissa Azab to give them a taste of what’s in store. Contributor James Purtill witnessed the results… ART DIRECTION & STYLING PHOTOGRAPHY Maissa Azab Khaled Fadda Marwan Mohsen: Trousers by Dior; Blazer & Tie by Dolce & Gabbana all available at Beymen Omar Gaber: Blazer & shirt by Neil Barrett; Tie by Dolce & Gabbana; Trousers by Emporio Armani all available at Beymen Mohamed Elneny: Suit, shirt & tie by Dolce & Gabbana; belt by Gucci all available at Beymen Euro 2012 ball available at adidas ohamed Nasr Elneny, Omar Gaber and Marwan Mohsen stand in front of a mirror in the photographer’s studio. They’re footballers, all un- der 23, and about to hit the big time. By the time you read this, they will be at the London 2012 Olym- pic Games. For the first time in 20 years, Egypt has qualified a team. Cue the publicity machine. Cue the photographer’s studio, the stylists, and the interviews-on-couch- es. Representatives from Vodafone, the main sponsor of the Olympic football team, are on hand to steer the players through Mthese hoops. They’re used to this, as Vodafone has been one of the main sponsors of the game since the telecom company launched in Egypt in 1998. They’re ready for the big-time. -

List of Recipients 2001-2018

Recipients of the Leigh Douglas Memorial Prize 2001-2018 2018 Joint Winners (£300 each) Cailah Jackson Patrons and Artists at the Crossroads: the Islamic Arts of the Book in the Lands of Rum, 1270s – 1370s (University of Oxford) This thesis presents the first detailed survey of a representative group of illuminated manuscripts produced in Anatolia in pre-Ottoman times, examining Qur’ans, mirrors for princes, historical chronicles, and Sufi works. In addition to examining 16 such manuscripts in appropriate detail, the thesis considers them more generally through quite another lens: namely that of the political and cultural environment of Anatolia (principally western Anatolia) between c.1270 and c.1370. This approach highlights the period’s ethnic and religious pluralism, the extent of cross-cultural exchange, the region’s complex political situation after the breakdown of Saljuq rule, and the impact of wandering scholars, Sufis and craftsmen....The strengths of the thesis lie in its thorough codicological examination of these 16 Persian and Arabic manuscripts, most of which have not been examined with this degree of depth before, and in so doing it constructs a framework for further research on similar manuscripts produced in this period and region. ...For art historians its rich array of illustrations, most of them still unpublished, will be of special interest. Altogether it brings into sharper focus than before the role of illuminated manuscripts in the cultural history of Anatolia in the 13th century....The thesis is very well written; the author’s style is elegant and lucid, which makes it a pleasure to read. She keeps a proper balance between three competing types of discourse: technical analysis of the manuscripts themselves, a detailed discussion of their patrons and their specific local context; and finally, more general discussion of such larger themes as religious pluralism, the cultural level of Turkmen princes, the fashion for mirrors for princes, the impact of the Black Death, and the pervasive impact of Sufism. -

Football Fan Communities and Identity Construction: Past and Present of “Ultras Rapid” As Sociocultural Phenomenon

Paper at “Kick It! The Anthropology of European Football” Conference, 25-26 October 2013 Football fan communities and identity construction: Past and present of “Ultras Rapid” as sociocultural phenomenon Philipp Budka & Domenico Jacono Introduction Eduardo Archetti (1992: 232) argues that “football is neither a ritual of open rebellion nor the much- mentioned opium of the masses. It is a rich, complex, open scenario that has to be taken seriously”. Archetti's argument is in line with the most recent research in fan and football fan culture (e.g. Giulianotti & Armstrong 1997, Gray, Sandvoss & Harrington 2007). Because to study fans and fandom means ultimately to study how culture and society works. In this paper we are going to discuss, within the framework of an anthropology of football, selected aspects of a special category of football fans: the ultras. By analysing the history and some of the sociocultural practices of the largest Austrian ultra group – “Ultras Rapid Block West 1988” – the paper aims to show how individual and collective fan identities are created in everyday life of football fan culture. “Ultras no fans!” is a slogan that is being found among ultra groups across Europe. Despite this clear “emic” statement of differentiation between “normal” football fans and “ultras”, ultras are, at least from a research perspective, basically fans. So we begin our examinations in the phenomenon of “Ultras Rapid” by briefly discussing anthropological and ethnographic research in football and football fans. We then set forth to present selected characteristics of SK Rapid Wien's largest ultra group that is also the oldest still active ultra movement in the German-speaking countries. -

Egypt As a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics'

H-Women Yilmaz on Baron, 'Egypt As a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics' Review published on Wednesday, October 22, 2008 Beth Baron. Egypt As a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. 292 pp. $60.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-520-23857-2. Reviewed by Hale Yilmaz Published on H-Women (October, 2008) Commissioned by Holly S. Hurlburt Nationalism, Gender, and Politics in Egypt In Egypt as a Woman Beth Baron explores the connections between Egyptian nationalism, gendered images and discourses of the nation, and the politics of elite Egyptian women from the late nineteenth century to World War Two, focusing on the interwar period. Baron builds on earlier works on Egyptian nationalist and women's history (especially Margot Badran's and her own) and draws on a wide array of primary sources such as newspapers, magazines, archival records, memoirs, literary sources such as ballads and plays, and visual sources such as cartoons, photographs, and monuments, as well as on the scholarship on nationalism, feminism, and gender. This book can be read as a monograph focused on the connections between nationalism, gender, and politics, or it can be read as a collection of essays on these themes. (Parts of three of the chapters had appeared earlier in edited volumes.) The book's two parts focus on images of the nation, and the politics of women nationalists. It opens with the story of the official ceremony for the unveiling of Mahmud Mukhtar's monumental sculpture Nahdat Misr (The Awakening of Egypt) depicting Egypt as a woman. Baron draws attention to the paradox of the complete absence of women from a national ceremony celebrating a work in which woman represented the nation.