The Great War in the Irish Juvenile Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Munster Fusiliers in France 1914-1918

,doned at the ime to OND MUNSTERS orders. ,ress of tics of n' was deput- mental asonic Le anti- 1s their he Royal Munster Army entered the town, they encount- :aders, Fusiliers were formed ered on the road a body of troops who ormer from the amalgamation of wore French uniforms and whose officer ster, in the 10lst and the 104th spoke in French. Suddenly, these troops, igious Foot Regiments, Bengal The Germans attacked on the 'without the slightest warning, lowered ligious Fusiliers. These two regiments became morning of Sunday, 23rd. As the battle their bayonets and charged'. They were ~g the the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the Royal raged all that day around the coal fields German soldiers and, like the 1st Army, ism of Munster Fusiliers, under an order passed of Mons, the Munsters somehow escaped were also scheduled to billet that night at I prove in July, 1881. Although the regimental the German onslaught. About 5 p.m. the Landrecies. General Haig, thinking he by the headquarters were in Tralee, many of the French 5th Army, which was to the right was under heavy attack, telephoned the lasonic fusiliers and their officers were of the fusiliers, began to give way and headquarters to send help. Assuming the Limerickmen. retreat. Due to a lack of communication worst, GHQ sent orders altering Haig's French After spending their first 33 years on between the French and the British, Sir line of retreat for the next day. his move 'S anti- tours of duty through much of the British John French, the British commander, did was to split the force in two, the result anuary, Empire, the Munsters were stationed at not receive news of the retreat until I1 being that the 1st and 2nd armies lost isit to Aldershot when the German invasion of p.m. -

From Ireland to America: Emigration and the Great Famine 1845 – 1852

Volume 2 Issue 4 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND March 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 From Ireland to America: Emigration and the Great Famine 1845 – 1852 Amira Achouri University of Grenoble Alpes, France Institute of languages and cultures in Europe, America, Africa, Asia and Australia Centre for Studies on the modes of Anglophone Representation [email protected] Abstract One of the changes that compose history is the migration of peoples. The human development of colossal numbers from one geographical area to another and their first contact with other social and economic backgrounds is a major source of change in the human state. For at least two centuries long before the great brook of the Hungry Forties, Irish immigrants had been making their way to the New World. Yet, the tragedy of the Great Famine is still seen as the greatest turning point of Irish history for the future of Ireland was forever changed. The paper tends to explore the conception of emigration and how it steadily became “a predominant way of life” in Ireland, so pervasive and integral to Irish life that it had affected the broad context of both Irish and American histories simultaneously. From the post-colonial perspective, my study presents emigration as one of the greatest emotional issues in Irish history, as it tends to have a very negative image especially in the post-Famine era. People are generally seen as involuntary “exiles”, compelled to leave Ireland by “British tyranny” and “landlord oppression” - an idealized Ireland where everyone was happy and gay and where roses grew around the door of the little white-washed cottage. -

The Reemergence of Emigration from Ireland

THE RE-EMERGENCE OF EMIGRATION FROM IRELAND NEW TRENDS IN AN OLD STORY By Irial Glynn with Tomás Kelly and Piaras Mac Éinrí TRANSATLANTIC COUNCIL ON MIGRATION THE RE-EMERGENCE OF EMIGRATION FROM IRELAND New Trends in An Old Story By Irial Glynn with Tomás Kelly and Piaras Mac Éinrí December 2015 Acknowledgments Much of the research on which this report is based was carried out as a result of a one-year Irish Research Council grant, which enabled the completion of the EMIGRE (“EMIGration and the propensity to REturn”) project at University College Cork between October 2012 to September 2013. The resulting paper was completed with the support of a Marie Curie Intra-European Fellowship within the 7th European Community Framework Program. Thanks go to Natalia Banulescu-Bogdan and Kate Hooper from the Migration Policy Institute for their insightful comments on earlier drafts. This research was commissioned by the Transatlantic Council on Migration, an initiative of the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), for its twelfth plenary meeting, held in Lisbon. The meeting’s theme was “Rethinking Emigration: A Lost Generation or a New Era of Mobility?” and this paper was one of the reports that informed the Council’s discussions. The Council is a unique deliberative body that examines vital policy issues and informs migration policymaking processes in North America and Europe. The Council’s work is generously supported by the following foundations and governments: Open Society Foundations, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Barrow Cadbury Trust, the Luso- American Development Foundation, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the governments of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. -

Global Irish: Ireland's Diaspora Policy

Éireannaigh anDomhain March 2015 March Beartas nahÉireannmaidirleisanDiaspóra Ireland’s Diaspora Policy Diaspora Ireland’s Irish Global Éireannaigh an Domhain Beartas na hÉireann maidir leis an Diaspóra Ireland’s Diaspora Policy Márta 2015 Global Irish Ireland’s DIASPORA POLICY 1 The Irish nation cherishes its special affinity with people of Irish ancestry living abroad who share its cultural identity and heritage Bunreacht na hÉireann 2 GLOBAL IRISH Our vision is a vibrant, diverse global Irish community, connected to Ireland and to each other. Ireland’s DIASPORA POLICY 3 Contents What’s New in this Policy? 4 Forewords 6 Introduction 10 Why a Review of Diaspora Policy? 13 Who are the Irish Diaspora? 16 Why Engagement with the Diaspora is so Important 19 The Role of Government 23 Supporting the Diaspora 25 Emigrant Support Programme 25 Welfare 27 Connecting with the Diaspora 31 Whole of Government Approach 31 Implementation 32 Local Activation for Global Reach 32 Communication 34 Culture 36 St. Patrick’s Day 38 Commemorations 39 Facilitating Diaspora Engagement 41 Partnerships 41 Networks 43 Returning Home 46 Diaspora Studies 47 Recognising the Diaspora 49 Presidential Distinguished Service Award for the Irish Abroad 49 The Certificate of Irish Heritage 50 Evolving Diaspora Policy 52 New Diaspora Communities 52 Alumni Engagement 53 Annex 1 - Presidential Distinguished Service Award for the Irish Abroad 54 Annex 2 - Membership of Interdepartmental Committee on the Irish Abroad 55 4 GLOBAL IRISH What’s New in this Policy? This is the first clear statement of Government of Ireland policy on the diaspora which recognises that Ireland has a unique and important relationship with its diaspora that must be nurtured and developed. -

The Contested Isle: the Hibernian Tribunal

The Contested Isle Credits AUTHORS: Mark Lawford, Christian Jensen Romer, Matt Ryan, AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES Mark Shirley DEVELOPMENT, EDITING, & PROJECT MANAGEMENT: David Chart Mark Lawford lives, works, and writes for Ars Magica in East- PROOFREADING, LAYOUT & ART DIRECTION: Cam Banks bourne, England. He’s also working on some original fiction, PROOFREADING ASSISTANCE: Jessica Banks & Michelle Nephew so please do wish him luck. He is very grateful to his fellow PUBLISHER: John Nephew author Matt Ryan for helping realize his aim of writing for COVER ILLUSTRATION: Christian St. Pierre a Tribunal book. CARTOGRAPHY: Matt Ryan Christian Jensen Romer is an unlikely candidate to write about INTERIOR ART: Jason Cole, Jenna Fowler, Christian St. Pierre, Ireland, being a Dane living in England. His passion for Irish Gabriel Verdon history and the medieval saints however led this to be his ADDITIONAL ART: Celtic Design. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, favorite Ars Magica project to date, and he hopes you find as Inc., 2007. much joy in it as he did. He would like to dedicate his part of ARS MAGICA FIFTH EDITION TRADE DRESS: J. Scott Reeves this book to the memory of Christina Jones, who taught him PUBLISHER’S SPECIAL THANKS: Jerry Corrick & the gang at the the little Irish he knows and told him tales of her homeland. Source. Matt Ryan works in a university library in upstate New York. His forefathers were early participants in the Irish diaspora FIRST ROUND PLAYTESTERS: Jason Brennan, Justin Brennan, Elisha and his family has been in the States for several generations. Campbell, Robert Major; Leon Bullock, Peter Ryan, Chris He visited Ireland in 2001, during which time he swam in Barrett, John A Edge; Eirik Bull, Karl Trygve Kalleberg, Hel- the cove on Cape Clear Island, where he would later place ge Furuseth, André Neergaard, Sigurd Lund; Donna Giltrap, the covenant Cliffheart. -

Ireland's Diaspora Strategy: Diaspora for Development?

IRELAND'S DIASPORA there has been insuJ 4 Irish emigrants an< changing nature of now being institut' Ireland's diaspora strategy: diaspora ments and semi-st diaspora and there for development? diaspora strategy. I diaspora strategy I Mark Boyle, Rob Kitchin and Delphine Ancien through which dia~ on some importan< then isolate three ; institutions and str identifying a numb diaspora strategy rr Diaspora and devc Introduction i In 2011, when the population of the Irish Republic stood at 4.58 million, over Growing interest 70 million people worldwide claimed Irish descent, and 3.2 million Irish countries of origin passport holders, including 800,000 Irish-born citizens, lived overseas Studies and the pra (Ancien et al., 2009). Despite being varied and complex, it is often assumed Dewind and Hold< that a strong relationship has prevailed between the Irish diaspora and Lowell and Gerov Ireland, with the diaspora operating transnationally, bequeathing a flow of Vertovec, 2007; Y< various exchanges (e.g. information, goods, money, tourist visits, political viewed as a baromc ment strategies. Th will) between diaspora members and family and social, cultural, economic and political institutions in Ireland. Nevertheless, throughout the early 2000s, being pursued by 1 skilled labour from Ireland's relationship with its diaspora was seen to be entering a new era in further weaken th< which ties to Ireland were seemingly weakening as the traditional imperatives however, countrie that helped to maintain a strong Irish identity across generations were -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………….……………………. 1 1. Ireland and Migration ………………………………………………….… 3 2. The Departure ……………………………………………………………. 22 3. Life Abroad ……………………………………………………….……… 34 4. The Return ………………………………………………………….……. 53 5. Exile at Home ……………………………………………………………. 70 6. Parents, Loss and Memory, Identity …...………………………………… 83 Conclusions ……………………………………………………………….…. 89 Works Cited …………………………………………………………………. 94 Lists of Photos and Other Visual Material………….………………………… 100 Introduction Emigration has been recurrent in Irish history and is consequently one of the major topics in Irish literature. No other country in Europe has experienced emigration on such a wide scale. Mary Robinson, Irish Prime Minister from 1990 until 1997 spoke about emigrants in her inaugural speech on 3rd December 1990 and in her dedicated speech “Cherishing the Irish Diaspora” in 1995. In her first speech she widened the concept of community by saying that “the State is not the only model of community with which Irish people can and do identify” and addressed the emigrants as “extended family abroad” (“Address by the President Mary Robinson”). The year 1845 is considered a turning point in migration from Ireland, following repeatedly failed potato crops, but the peak of emigration in the same century was in the 1880s; the peak of the following century was around 1956-1961. According to Fintan O’ Toole “the journeys to and from home are the very heartbeat of Irish culture” (158). It is no wonder so many Irish writers have dealt with the topic of emigration, including poets, novelists, and playwrights. While any literary genre can express the feelings and use the language of the people it represents, “drama and its constructive categories of dialogue, interaction and immediacy in performance have by definition always had a close affinity to the structures of the particular society they reflect” (Middeke and Schnierner, vii). -

Community Action Plan 2019 - 2024 Draft June 2019 TABLE of CONTENTS

TEMPLEMORE COMMUNITY ACTION PLAN Draft Issue 2019 - 2024 for Community June Feedback 2019 Only! Templemore Community Action Plan 2019 - 2024 Draft Issue 14th June 2019 Draft for Community June Feedback 2019 Only! Tipperary Local Community Development Committee (LCDC) is the managing body for the European Union Rural Development 2014 -2020 (LEADER) Programme in County Tipperary. This project has been co-funded under the EU Rural Development 2014 -2020 (LEADER) Programme implemented in County Tipperary by North Tipperary Development Company on behalf of the Tipperary LCDC. Acknowledging the assistance of the EU and The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development: Europe Investing in Rural Areas. Funded by the Irish Government under the National Development Plan 2014 -2020 GEARÓID FITZGIBBON FOREWORD MR. TOM PETERS, CHAIR OF TEMPLEMORE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Welcome to the Templemore Town 5 Year Community Action Plan; an exciting devel- The Steering Committee of the TCDA together with its Associate Members opment to enhance our town and its hinterland as a great place to live, work, visit and has guided the development of this 5 Year Community Action Plan and will do business in. This plan is being promoted by Templemore Community Development play a key role in commencing its implementation. Association (TCDA) with the purpose of enabling the potential of the Town to be realised and sustained, as well as providing a focus to empower the community to enhance and The Steering Committee members include: improve the socio-economic and quality of life in Templemore. Tom Peters (Chair) Michael Connell Declan Glynn Pat Hassey Templemore is of course already a great place to live and has a very strong ethos of Ronan Loughnane volunteerism and community spirit which is demostrated by the many community, sport- Sally Loughnane Kevin Ludlow Myles McMorrow Michael O’Brien ing and social organisations and facilities in the town. -

The Second Munsters 1914-1918 (Part Two)

ife in the trenches was indescribably miserable. There were three lines of trenches; the first, at the front line, was proteaed bv m-ach- ine-guns and baibed wire entangle- ments; behind were the support and reserve trenches. It was said of the Munsters that they 'waste men wic- kedly' because they did not keep prop- erly under cover in the reserve lines.'. To get from one trench to another they had to pass through what was known as the communication trench. Through this network ran the telephone wires which were fastened by staples to the side of the trenches. When it rained, the staples fell out and the wires fell down, tripping the soldiers as they moved by Des Ryan through the trenches. Part Two For a newcomer, travelling by night in the trenches was a hazard. If the would slip, unnoticed, "into the slime when these shells exploded, they gave wires did not trip him up, he was liable and would often drown and lie con- off clouds of black smoke. Another to fall into a hidden hole. The trenches cealed for days'.2 shell was called a 'Whizz Bang', were dug in a zig-zag pattern in orderto Standing in muddy water for hours because, unlike a normal shell which contain a bomb explosion and also to caused the feet to swell and rot (this gave off a shrieking sound as it stop the enemy soldiers from firing condition was known as 'trench feet'). approached, this one arrived silently. down the full length of the trench. A The soldiers also caught trench-fever. -

The History of MUNSTER HALL 1899 - Today

The History of MUNSTER HALL 1899 - today 1899 - 1913 - 1925 - 1973 - 1905 1919History1962 today 1905 - 1919 - 1962 - 1912 1925 1973 Preface One of the great things about working in an old building like ours (apart from the drafty corners) are the stories that we hear everyday across the counter. And so, a couple of years ago, we decided to find out as much as possible about one of Limerick's old Halls. The street We get asked all the time ' where does the street name come from' as it's difficult both to spell and pronounce if you have not heard it before. In 1760, Limerick was proclaimed an open city and the demolition of the medieval walls began. Around this time the building of the Georgian town commenced. The main leaders connected with the movement to create Newtown Pery were Edmund Sexton Pery, who owned most of the land, his brother-in-law, Sir Henry Hartstonge, the Russells and the Arthurs. Hartstonge Street is named after Bruff born Henry, a Irish politician, and his wife Lady Lucy Hartstonge, who was renowned for her charitable work in Limerick including the founding of St. John's Hospital. The streetscape Pre 1850, there was no definition between Upper and Lower - it was simply called Hartstonge Street. Upper Hartstonge Street, like Barrington Street and Upper Mallow Street, housed the wealthier families. Lower Hartstonge Street, which was sandwiched between Newtown Pery and the river, presented more a modest housing arrangement. There were families living here as well as boarding houses for unmarried workers and trades people. -

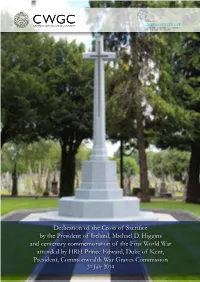

Dedication of the Cross of Sacrifice by the President of Ireland, Michael D

Dedication of the Cross of Sacrifice by the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins and centenary commemoration of the First World War attended by HRH Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, President, Commonwealth War Graves Commission 31 July 2014 The Last Absolution of the Munsters at Rue du Bois by Father Francis Gleeson Chairman’s Address The dedication of the Cross of Sacrifice and the centenary commemoration of the outbreak of the First World War is a hugely significant event for Glasnevin Trust. This is one of a number of major commemorations taking place in the Cemetery during the “Decade of Centenaries”. Already this year we have had a very important commemoration to mark the centenary of the founding of “Cumann na mBan” led by President Higgins and featured the first all female personnel guard of honour in the history of the state and possibly in the world! The decade we are remembering is complex. As Europe and much of the rest of the World prepares to commemorate the start of World War 1, it is noticeable, even after one hundred years, that there is no consensus on what actually caused the outbreak. This period of history on this Island is even more complex as we must not forget that the decade ended in independence and retention of the Union. This commemoration and the exhibition opened in our museum will, hopefully, push back the door further on this intricate part of our history. It should remind us of our shared history amongst the two traditions on this Island. One in six of those eligible enlisted, at least 210,000, and of those one in five perished. -

A Letter from Ireland

A Letter from Ireland Mike Collins lives just outside Cork City, Ireland. He travels around the island of Ireland with his wife, Carina, taking pictures and listening to stories about families, names and places. He and Carina blog about these stories and their travels at: www.YourIrishHeritage.com A Letter from Ireland Irish Surnames, Counties, Culture and Travel Mike Collins Your Irish Heritage First published 2014 by Your Irish Heritage Email: [email protected] Website: www.youririshheritage.com © Mike Collins 2014 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilised in any form or any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or in any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. All quotations have been reproduced with original spelling and punctuation. All errors are the author’s own. ISBN: 978-1499534313 PICTURE CREDITS All Photographs and Illustrative materials are the authors own. DESIGN Cover design by Ian Armstrong, Onevision Media Your Irish Heritage Old Abbey Waterfall, Cork, Ireland DEDICATION This book is dedicated to Carina, Evan and Rosaleen— my own Irish Heritage—and the thousands of readers of Your Irish Heritage who make the journey so wonderfully worthwhile. Contents Preface ...................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................ 4 Section 1: Your Irish Surname .......................................