Impact Report October 2019 Professor Andrew Parker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Julie Harrington Named New BHA CEO Cont

WEDNESDAY, 12 AUGUST 2020 JULIE HARRINGTON PHOENIX THOROUGHBREDS TO CEASE UK OPERATIONS NAMED NEW BHA CEO Phoenix Thoroughbreds has announced that it will end its racing operations in the UK with immediate effect. Phoenix Thoroughbreds has been embroiled in controversy since last November when its chief executive officer Amer Abdulaziz Salman was named in a U.S. federal court trial as being involved in a money-laundering operation. Abdulaziz was also accused of stealing money from sham cryptocurrency OneCoin, which he purportedly helped to run. Abdulaziz has repeatedly denied the allegations. A statement from Phoenix on Tuesday read in part, Aeverybody at Phoenix Thoroughbreds is keen for investment into the international sport of racing and in the past few years has been fully committed to healthy growth. The company has conducted itself appropriately, despite certain media outlets claiming otherwise.@ Cont. p2 Julie Harrington will take over as CEO of the British Horseracing IN TDN AMERICA TODAY Authority on Jan. 4 | Courtesy BHA KEENELAND RELEASES SEPTEMBER CATALOGUE The catalog for the world-renowned Keeneland September The British Horseracing Authority (BHA) has announced the Yearling Sale, to be held Sept. 13-25, features 4,272 offerings appointment of Julie Harrington to the role of chief executive Click or tap here to go straight to TDN America. from January 2021. A former BHA board member during her eight years as a senior executive with Northern Racing, Harrington has been the CEO of British Cycling for almost four years. She has also previously been managing director of Uttoxeter Racecourse and operations director of the Football Association (FA), during which time she was responsible for Wembley Stadium and the FA's training facility, St George's Park. -

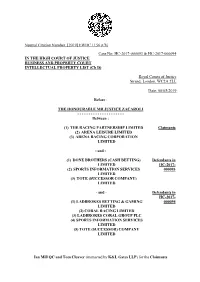

High Court Judgment Template

Neutral Citation Number: [2019] EWHC 1156 (Ch) Case No: HC-2017-000093 & HC-2017-000094 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURT INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LIST (Ch D) Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 08/05/2019 Before : THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE ZACAROLI - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : (1) THE RACING PARTNERSHIP LIMITED Claimants (2) ARENA LEISURE LIMITED (3) ARENA RACING CORPORATION LIMITED - and - (1) DONE BROTHERS (CASH BETTING) Defendants in LIMITED HC-2017- (2) SPORTS INFORMATION SERVICES 000093 LIMITED (3) TOTE (SUCCESSOR COMPANY) LIMITED - and - Defendants in HC-2017- (1) LADBROKES BETTING & GAMING 000094 LIMITED (2) CORAL RACING LIMITED (3) LADBROKES CORAL GROUP PLC (4) SPORTS INFORMATION SERVICES LIMITED (5) TOTE (SUCCESSOR) COMPANY LIMITED Ian Mill QC and Tom Cleaver (instructed by K&L Gates LLP) for the Claimants Michael Bloch QC and Craig Morrison (instructed by CMS Cameron McKenna Nabarro Olswang LLP) for the Second Defendant (in HC-2017-000093) and Fourth Defendant (in HC-2017-000094) Hearing dates: 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 23, 28, 29, 31 January 2019 & 1 February 2019 Post-trial written submissions 8 March 2019 & 15 March 2019 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment I direct that pursuant to CPR PD 39A para 6.1 no official shorthand note shall be taken of this Judgment and that copies of this version as handed down may be treated as authentic. ............................. MR JUSTICE ZACAROLI MR JUSTICE ZACAROLI Racing Partnership v Ladbrokes Et al Approved Judgment A. Introduction 1 B. The horseracing data in issue 7 (i) Betting Prices 8 (ii) Raceday Data 13 (iii) The commercial value of Betting Shows and Raceday Data 14 C. -

Newsletter Update

www.racecourseassociation.co.uk December 2018 December updatenewsletter CONTENTS Welcome 03 Raceday Experience Group 05 5 Did You Know ... 07 Racecourse Grounstaff Courses 07 Badges & Pass 2018 08 Racegoers Club 10 Five Minutes of Fame 12 Racehorse Owners Association 13 RaceTech 14 GBRI 15 Racing Foundation 16 Racing to School 17 Racing Together 18 The Thoroughbred Club 18 Thoroughbred Breeders Assoc. 19 Careers in Racing 20 Watt Fences 22 Duralock 23 Sporting Edge 24 Diary Dates / Contributors / 25 Staff Contact List 11 14 18 2 | RCA Update Newsletter 2018 Back to content page WELCOMEWords by Paul Swain presentation this week from our Our December Update is packed full Racing Assistant Megan Bouwman. of content to keep you going through Megan has made the transition from your Christmas dinner until the Queen’s stable life to office life over the past speech. We check-in with the Raceday few years, starting with the BHA Experience Group after their December Graduate Development Programme meeting at Musselburgh, the latest On and progressing to the Northern Racing Track looks at our recent survey with College and now the RCA via stints the NTF around trainers’ motivations with Harry Fry and Clive Cox. Megan’s to run their horses and we sit down with enthusiasm for all things racing is clear Doncaster’s new Executive Director to anyone who meets her and to hear Russell Smith who is probably the first-hand from someone who has been biggest Hibs fan you’ll find in Yorkshire. involved with successful training yards Finally, a big congratulations to all at and the care, attention and teamwork Chester and Bangor who were recently required to train thoroughbreds was crowned large and small racecourses inspiring for the full team. -

SUMMER MAGAZINE 2019 INTRODUCTION P ARK HOUSE STABLES Orse Racing Has Always Been Unpredictable and in Many Ways That Is Part of Its Attraction

P ARK HOUSE STABLES SUMMER MAGAZINE 2019 INTRODUCTION P ARK HOUSE STABLES orse racing has always been unpredictable and in many ways that is part of its attraction. It can provide fantastic high H points but then have the opposite effect on one’s emotions a moment later. Saturday 13 July was one of those days. Having enjoyed the thrill of watching Pivoine win one of the season’s most important handicaps, closely followed by Beat The Bank battling back to win a second Summer Mile, the ecstasy of victory was replaced in a split second by a feeling of total horror with Beat The Bank suffering what could immediately be seen to be an awful injury. Whilst winning races is important to everyone at Kingsclere, the vast majority of people who work in racing do it because they love horses and there is nothing more cruel in this sport than losing a horse, whether it be on the gallops or on the racecourse. Beat The Above: Ernie (Meg Armes) is judged Best Puppy at the Kingsclere Dog Show Bank was a wonderful racehorse and a great character and will be remembered with huge affection by everyone at Park House. Front cover: BEAT THE BANK with Sandeep after nishing second at Royal Ascot Whilst losing equine friends is never easy it is not as difficult as Back cover: LE DON DE VIE streaks clear on Derby Day at saying goodbye to two wonderful friends in Lynne Burns and Dr Epsom Elizabeth Harris. Lynne was a long time member of the Kingsclere Racing Club and her genial personality and sense of fun endeared CONTENTS her to everyone lucky enough to meet her. -

44082 44082 Nass Quarterly.Indd

STABLE NARS Newsletter - December 2017 talk Pg2 Pg10 Pg11 Pg12 George’s Column Goodwood Golf Days Sports Events NARS Head Office: The Racing Centre, Fred Archer Way, Newmarket, Suffolk, CB8 8NT T: 01638 663411 E: [email protected] W: www.naors.co.uk CATCH 22 Catch 22 is defined as a dilemma or difficult circumstance from which there is no escape. That definition perfectly describes the situation the racing staff of Great Britain finds itself in at the moment. Many of you will know from either talking to me or reading the newsletters that I have been trying to get an agreement from the trainers on working hours and more time off for the staff. racing and by doing so put even more The reality of the situation is that todays pressure on the remaining staff meaning there society and therefore the workforce coming is even less likelihood of them getting the into it simply will not accept working 13 out time off that would enable them to once again of 14 mornings a fortnight, especially as the have a work/life balance and enjoy working mornings tend to start at anything between with horses again. Catch 22 in a nutshell. 5am and 6am. So that coupled with the fact Yet it doesn’t have to be like this, in France most of the racing staff only get one and a they work a 35 hour week and they still train half days off per fortnight is why we are facing Group 1 winners! A few yards around the a staffing shortage soon to become a crisis country work a rota whereby half the staff if we are already not at that stage. -

View Annual Report

Arena Leisure Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2010 More than a day at the races Arena Leisure Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2010 Horseracing lies at the heart of Arena’s activities. Our portfolio of racecourse assets provides a solid base for the future development of the Group into a range of complementary, income-generating activities that enhance our racing business and allow the expansion of our racecourses into 365 days a year operations. hospitality hotels all-weather and leisure turf and Áoodlit racing horseracing golf media broadcast exhibitions conferencing and events and banqueting Arena Leisure Plc 01 Annual Report and Accounts 2010 2010 Highlights Overview Overview 01 2010 Highlights 02 At a Glance 04 Chairman’s Statement 06 Chief Executive’s Statement Revenue £63,983,000 Strategy Strategy 2010 £63,983,000 2009 £65,239,000 08 Market Overview 11 Strategy and Business Model 13 Resources ReportDirectors’ and Business Review Adjusted profit before 14 Key Performance Indicators interest and tax £5,414,000 16 Principal Risks 2010 £5,414,000 2009 £4,904,000 Performance Operational highlights Performance 19 Review of Operations Average attendance increased by 4.2% 22 Managing Responsibly to 1,800 ahead of the market average 23 Financial Review growth of 3.4% Hospitality attendance increased by 17.1% to 45,200 At The Races delivered a 163% increase in post-tax contribution of £1.4m Governance Governance 25 Board of Directors and Company Secretary Development highlights 26 Corporate Governance 30 Other Statutory Information LingÀeld -

The Newmarket Town Plate Saturday 28Th August 2021 the Round Course, Newmarket Entry Form

Ref. AM012021 THE NEWMARKET TOWN PLATE SATURDAY 28TH AUGUST 2021 THE ROUND COURSE, NEWMARKET ENTRY FORM RIDER DETAILS RIDER’S NAME: (Mr. Mrs. Miss. Please denote) DATE OF BIRTH: ACTUAL WEIGHT: RIDING WEIGHT: ADDRESS: TELEPHONE: EMAIL: OCCUPATION OF RIDER: QUALIFICATION OF RIDER: (A, B, C or D – see race conditions) COLOURS TO BE WORN: (include body colour & markings; sleeve colour & markings; cap colour & markings) NEXT OF KIN: (include name, contact telephone number & address) RIDERS ASSESSMENT & FITNESS TEST: Wednesday 9th June – Northern Racing College, Doncaster (Please tick your preferred date & Location) TBC – British Racing School, Newmarket 1 Ref. AM012021 MEDICAL • All applicants must complete and pass a BHA Medical (Appendix ii) • A BHA Medical is valid for 5 years*. • Organisers reserve the right to use their discretion and may request a medical more often in individual cases DECLARATION OF HEALTH RIDER NAME: NAME OF GP: GP ADDRESS: DATE OF LAST BHA MEDICAL EXAMINATION (if applicable)* HAVE YOU SUFFERED FROM ANY INJURIES OR SERIOUS ILLNESSES SINCE YOUR LAST BHA MEDCIAL EXAMINATION: (IF YES, PLEASE GIVE DETAILS) ARE YOU AT PRESENT RECIEVEING ANY TREATMENT OR REGULAR MEDICATION SUPERVISED BY YOUR DOCTOR? IF YES PLEASE GIVE DETAILS: DO YOU SUFFER FROM ANY ALLERGIES? IF YES PLEASE GIVE DETAILS: *Applicants who are aged 50 or over will be required to renew their BHA Medical every 2 years. 2 Ref. AM012021 HORSE DETAILS HORSE’S NAME: D.O.B: COLOUR & SEX: BREEDING: (DAM & SIRE) QUALIFICATION OF HORSE: (A, B or C – see race conditions) COLOURS TO BE WORN: (include body colour & markings; sleeve colour & markings; cap colour & markings) EQUIPMENT TO BE WORN: (tongue tie/visor/hood etc.) OWNERS NAME: ADDRESS: TELEPHONE & EMAIL: TRAINER’S NAME: ADDRESS: TELEPHONE & EMAIL: RESERVE ENTRY: (IF YES, PLEASE COMPLETE YES NO PAGE 4) 3 Ref. -

Download the Workbook Here

Welcome to Racing to School! Name: ................................................................................................................................... School: .................................................................................................................................. Venue: ................................................................................................................................... Date:..................................................................................................................................... Racing to School is a registered charity responsible for developing and delivering the Racing to School education programme. Racing to School supports and enriches the learning and development of pupils and students of all ages throughout the UK, using the context of racing and thoroughbred breeding to deliver excitin g, hands-on activities in an open air , healthy environmen t. Racin g to School is a key part of British Racin g’s community engagement programme, RRacing Together . Racing to School supports The Horse Comes First initiative which aims to improve understanding of the ca re given to horses throughout and after their careers inin racing . The Racing to School programme has been officially recognised as a quality Lea rning Outside the Classroom provider . The LOtC Quality Badge emphasises our commitment to providing a high quality programme to children, young people and schools . 2 Weighing Out 1. What happens in the Weighing Room? a) The horses are weighed -

Night of Thunder Colt Tops Craven Cont

FRIDAY, 26 JUNE 2020 NIGHT OF THUNDER BALLYDOYLE SIX IN LINE FOR IRISH DERBY CHALLENGE COLT TOPS CRAVEN Aidan O=Brien has declared six colts among the field of 15 set to go to post for Saturday=s G1 Dubai Duty Free Irish Derby at The Curragh, with last week=s G2 Queen=s Vase winner Santiago (Ire) (Authorized {Ire}) looking the first string with Seamie Heffernan up. Wayne Lordan rides the G2 King Edward VII S. runner-up Arthur=s Kingdom (Ire) (Camelot {GB}) in the largest field to grace the Classic since 1977. Santiago, who drops back two furlongs following his impressive Royal Ascot victory, has been done no favours by the draw with a wide posting in 11, while Joseph O=Brien=s main chance Crossfirehurricane (Kitten=s Joy) will also have to navigate a high draw in 13. Scott Heider=s unbeaten G3 Gallinule S. scorer will be joined by the supplemented June 13 G1 Irish 1000 Guineas fourth New York Girl (Ire) (New Approach {Ire}), who exits from stall 14 as the sole filly in the line-up. Jim Bolger relies on the maiden Fiscal The 575,000gns Night Of Thunder colt | Tattersalls Rules (Ire) (Make Believe {GB}), who was fifth in the G1 Irish 2000 Guineas on June 12 and the homebred is drawn five, one out from Arthur=s Kingdom who sports first-time cheekpieces. By Emma Berry Cont. p7 NEWMARKET, UK--Thunder is indeed expected in Newmarket as the scorching hot snap comes to an end but it appeared early at Tattersalls on Thursday when Darley's up-and-coming sire Night Of Thunder (Ire) was represented by the leading juvenile, at 575,000gns, of the Craven Breeze-up Sale. -

July 2019 CONTENTS

www.racecourseassociation.co.uk July 2019 updatenewsletter CONTENTS Welcome 03 Raceday Experience Forum 06 06 On Track 08 Did You Know... 10 RCA Medical Group 11 Badges & Pass 2019 12 Racegoers Club 13 Five Minutes of Fame 15 GBRI 16 Racing to School 17 Racing Together 18 Racing Foundation 19 Injured Jockeys Fund 20 HBLB 21 ROA 21 RaceTech 22 TBA 23 Careers in Racing 24 Duralock 26 Overview of British Racing 27 Diary Dates / Contributors / Staff 28 Contact List 09 17 19 Front Cover: Image courtesy of Sandown Park Racecourse 2 | RCA Update Newsletter 2019 Back to content page WELCOMEWords by Paul Swain and those of us who were fortunate to can’t wait to welcome Harry Phipps to be present will never forget the roar of the team—look out for August’s Update the crowd and the celebrations. Such where Harry will have his own column to events are a genuine feather in the cap introduce himself. of our sport and all who played a part in British Racing’s career development is that moment should be proud of the one that is of the envy of many other memories they were able to create. industries. Whether you have grown Of course, the good times continued up in an equine environment or have to roll for the Gosden/Dettori team no background in the sport other than with the heroine Enable proving she as a fan, there are opportunities to retains every bit of star quality in the embark on a career within the sport. Coral Eclipse. -

![Neutral Citation No: [2005] CAT 29 in THE](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9726/neutral-citation-no-2005-cat-29-in-the-5439726.webp)

Neutral Citation No: [2005] CAT 29 in THE

Neutral Citation No: [2005] CAT 29 IN THE COMPETITION Case Nos: 1035/1/1/04 APPEAL TRIBUNAL 1041/2/1/04 Victoria House, Bloomsbury Place, London WC1A 2EB 2 August 2005 Before: THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE RIMER PROFESSOR ANDREW BAIN MRS SHEILA HEWITT Sitting as a Tribunal in England and Wales BETWEEN: THE RACECOURSE ASSOCIATION AND OTHERS Appellants and OFFICE OF FAIR TRADING Respondent AND THE BRITISH HORSERACING BOARD Appellant and OFFICE OF FAIR TRADING Respondent Mr Christopher Vajda QC and Mr Sam Szlezinger (instructed by Denton Wilde Sapte) appeared for The Racecourse Association and its co-appellants Mr David Vaughan QC and Miss Maya Lester (instructed by Addleshaw Goddard) appeared for The British Horseracing Board Mr Rhodri Thompson QC and Mr Julian Gregory (instructed by the Solicitor to the Office of Fair Trading) appeared for the Office of Fair Trading Heard at Victoria House on 14, 15 and 16 March 2005 JUDGMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS I INTRODUCTION............................................................................................1 II THE CHAPTER I PROHIBITION ...............................................................4 III THE APPEALS TO THIS TRIBUNAL ........................................................6 IV FUNDING OF RACING BY BETTING AND OTHERWISE....................7 V THE RACECOURSES....................................................................................9 VI EVENTS LEADING UP TO THE MRA.....................................................11 VII THE MRA.......................................................................................................32 -

March 2018 CONTENTS

www.racecourseassociation.co.uk March 2018 updatenewsletter CONTENTS Welcome 03 Sport Relief 05 08 Showcase & Awards 2018 06 QARS Results 2017 07 Racecourse in Focus 08 RCA Racing & Turf Management 09 Conference / Did You Know ... 09 RCA Racing Department / 10 Groundstaff Courses 10 Badges & Pass 2018 11 Sports & Recreation Alliance 12 Racegoers Club 13 Five Minutes of Fame 15 Wi-Fi Upgrades 16 GBRI 17 BHA 18 Racing Foundation 19 RaceTech 20 Racing to School 21 Racing Together 22 The Silk Series 23 The Thoroughbred Club 24 Thoroughbred Breeders Assoc. 24 HBLB / ROA 25 Racing Welfare & Betfair 26 Horseracing Bettors Forum 27 New Clerk of the Course 28 17 Watt Fences 30 Duralock 31 Careers in Racing 32 British Racing Overview Seminar 33 Diary Dates / Contributors / 34 Staff Contact List 21 24 2 | RCA Update Newsletter 2018 Back to content page WELCOME With the snow gone and spring in the air there is lots to look forward to in the coming months and we’ve got a packed edition of Update to get you started. Words by Will Aitkenhead subject and clearly the investment going into this area and work of the Racecourse Experience Group and Showcase is having a positive impact. One of the purposes of the scheme is to enable racecourses to benchmark how they compare with competitors – namely other sporting and leisure venues. To have the two recognised tourist boards providing such positive assessments is very pleasing and we hope the improvement will continue year on year. We were proud to sit with our industry colleagues at the recent Roadshows in York, Newbury and Newmarket.