Neutral Citation No: [2005] CAT 29 in THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 Primrose Drive, Ripon, North Yorkshire, HG4 1EY Guide Price £420,000

11 Primrose Drive, Ripon, North Yorkshire, HG4 1EY Guide price £420,000 www.joplings.com We are delighted to offer to market a Five Bedroom Detached family home with versatile, extended living accommodation, situated in a quiet cul-de-sac in the popular Palace Road area of Ripon. The property benefits from Gardens to all sides and a Double Garage with Driveway Parking. www.joplings.com DIRECTIONS flooring. Contemporary vertical wall-mounted radiator. Cupboard OUTSIDE From our Ripon Office on North Street, head North to the Victoria Clock housing the Vaillant gas combi boiler. Recessed lighting. Tower traffic lights. Turn left into Palace Road (A6108) and take the first turning on the left hand side into Primrose Drive. Follow the road round CONSERVATORY TO THE FRONT to the left and the property will be found on the left hand side. UPVC Conservatory with doorway leading out to the Patio seating area. Walled front boundary with hedging and shrubs. Pedestrian access gate Tiled flooring with underfloor heating. and pathway leads to the Front Entrance door. Garden mainly laid to ADDITIONAL SITUATIONAL INFORMATION lawn. Steps lead down to a trellis archway leading around to the Rear Ripon is the third smallest city in England and is known for the imposing UTILITY ROOM Garden. Cathedral, Ripon Racecourse and the nearby, Fountains Abbey and UPVC part-glazed door leading out to the Rear of the property with a Studley Royal Gardens. Ripon Market Place is at the centre of the City further window to the side. Deep Belfast Sink. Space and plumbing for GARAGE with a variety of local shops and amenities within easy walking distance. -

Please Click Here for Racecourse Contact Details

The Racing Calendar COPYRIGHT UPDATED: MONDAY, JUNE 14TH, 2021 RACECOURSE INFORMATION Owners may purchase additional badges and these badges AINTREE ASCOT may be purchased at the main entrance and will admit partnership or syndicate members to the owners’ and trainers’ facilities only on the day that their horse is running. Numbers of additional badges must be agreed in advance. PASS is operational at all fixtures EXCLUDING Clerk of the Course Miss Sulekha Varma Clerk of the Course C. G. Stickels, Esq. ROYAL ASCOT. Tel: (0151) 523 2600 Tel: Ascot (01344) 878502 Enquiries to PASS helpline Tel: (01933) 270333 Mob: (07715) 640525 Fax: Ascot (0870) 460 1250 Fax: (0151) 522 2920 Email: [email protected] Car Parking Email: [email protected] Ascot Racecourse, Ascot, Berkshire, SL5 7JX Owners are entitled to free car parking accommodation Chairman Nicholas Wrigley Esq. Chief Executive G. Henderson, Esq. in the owners car park, situated in Car Park No. 2, on the North West Regional Director Dickon White Medical Officers Dr R. Goulds, M.B., B.S., day that their horse is declared to run. No more than two Veterinary Surgeons J. Burgess, T. J. Briggs, Dr R. McKenzie, M.B., B.S., spaces are allocated for each horse. The car park is A. J. M. Topp, Prof. C. J. Proudman, Dr E. Singer, Dr J. Heathcock, B.Sc., M.B, Ch.B, Dr J. Sadler M.B., B.S., situated on the A329, three hundred yards from the K. Summer, J. Tipp, S. Taylor, P. MacAndrew, K. Comb Dr D. Smith M.B., B.S., Dr J. -

Ure Corridor Recreation Area

A The Marina. AREA 75 Approved UreUre CorridorCorridor recreationrecreation areaarea Feb 2004 (Ripon(Ripon ToTo NewbyNewby Reach)Reach) Description This is an area of intensive recreational use situated along the eastern edge of Ripon and covering almost 4km² of the Ripon Canal and River Ure corridor. The two water courses run almost parallel to each other in a north-south direction through the area to the point where they meet approximately one mile upstream of Newby Hall. The watercourses are well-wooded providing an intimate and attractive setting for boaters and walkers with dispersed views into the landscape beyond. A strong network of public footpaths provides easy access to the banks of the canal and much of the riverbank and is a valuable resource to the local community. Beyond the watercourses, the flat landscape is more open and management is a mixture of wild looking wetland with outgrown hedges and unkempt vege tation that contrast with the manicured appearance of the marina, sailing club and racecourse. Built form and boundary treatments display a variety of styles and modern materials that lack cohesion giving a somewhat chaotic appearance to this pleasant area. Key Characteristics Geology, soils and drainage Magnesian limestone solid geology overlain with alluvial drift geology. ©Crown Copyright. All Rights Reserved. Deep, stoneless, permeable, coarse loamy Harrogate Borough Council. 1000 19628 2004. brown soils and slowly-permeable, seasonally- waterlogged, clayey and fine, loamy over HARROGATE DISTRICT Location in Harrogate District Landscape Character Assessment clayey surface water gley soils. Landform and drainage pattern Area boundary* Not to Flat landform below 20m AOD Camera location Scale & direction The River Ure and associated tributaries along with Ripon Canal are the dominant NB Due to the nature of landform, surface treatment and soil/geology composition Character watercourses. -

Julie Harrington Named New BHA CEO Cont

WEDNESDAY, 12 AUGUST 2020 JULIE HARRINGTON PHOENIX THOROUGHBREDS TO CEASE UK OPERATIONS NAMED NEW BHA CEO Phoenix Thoroughbreds has announced that it will end its racing operations in the UK with immediate effect. Phoenix Thoroughbreds has been embroiled in controversy since last November when its chief executive officer Amer Abdulaziz Salman was named in a U.S. federal court trial as being involved in a money-laundering operation. Abdulaziz was also accused of stealing money from sham cryptocurrency OneCoin, which he purportedly helped to run. Abdulaziz has repeatedly denied the allegations. A statement from Phoenix on Tuesday read in part, Aeverybody at Phoenix Thoroughbreds is keen for investment into the international sport of racing and in the past few years has been fully committed to healthy growth. The company has conducted itself appropriately, despite certain media outlets claiming otherwise.@ Cont. p2 Julie Harrington will take over as CEO of the British Horseracing IN TDN AMERICA TODAY Authority on Jan. 4 | Courtesy BHA KEENELAND RELEASES SEPTEMBER CATALOGUE The catalog for the world-renowned Keeneland September The British Horseracing Authority (BHA) has announced the Yearling Sale, to be held Sept. 13-25, features 4,272 offerings appointment of Julie Harrington to the role of chief executive Click or tap here to go straight to TDN America. from January 2021. A former BHA board member during her eight years as a senior executive with Northern Racing, Harrington has been the CEO of British Cycling for almost four years. She has also previously been managing director of Uttoxeter Racecourse and operations director of the Football Association (FA), during which time she was responsible for Wembley Stadium and the FA's training facility, St George's Park. -

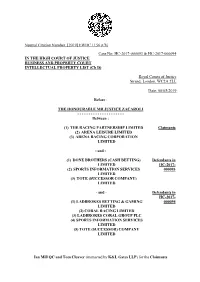

High Court Judgment Template

Neutral Citation Number: [2019] EWHC 1156 (Ch) Case No: HC-2017-000093 & HC-2017-000094 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURT INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LIST (Ch D) Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 08/05/2019 Before : THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE ZACAROLI - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : (1) THE RACING PARTNERSHIP LIMITED Claimants (2) ARENA LEISURE LIMITED (3) ARENA RACING CORPORATION LIMITED - and - (1) DONE BROTHERS (CASH BETTING) Defendants in LIMITED HC-2017- (2) SPORTS INFORMATION SERVICES 000093 LIMITED (3) TOTE (SUCCESSOR COMPANY) LIMITED - and - Defendants in HC-2017- (1) LADBROKES BETTING & GAMING 000094 LIMITED (2) CORAL RACING LIMITED (3) LADBROKES CORAL GROUP PLC (4) SPORTS INFORMATION SERVICES LIMITED (5) TOTE (SUCCESSOR) COMPANY LIMITED Ian Mill QC and Tom Cleaver (instructed by K&L Gates LLP) for the Claimants Michael Bloch QC and Craig Morrison (instructed by CMS Cameron McKenna Nabarro Olswang LLP) for the Second Defendant (in HC-2017-000093) and Fourth Defendant (in HC-2017-000094) Hearing dates: 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 23, 28, 29, 31 January 2019 & 1 February 2019 Post-trial written submissions 8 March 2019 & 15 March 2019 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment I direct that pursuant to CPR PD 39A para 6.1 no official shorthand note shall be taken of this Judgment and that copies of this version as handed down may be treated as authentic. ............................. MR JUSTICE ZACAROLI MR JUSTICE ZACAROLI Racing Partnership v Ladbrokes Et al Approved Judgment A. Introduction 1 B. The horseracing data in issue 7 (i) Betting Prices 8 (ii) Raceday Data 13 (iii) The commercial value of Betting Shows and Raceday Data 14 C. -

Pot Lid Out, Wally Bird in Owners Epiris in 2016

To print, your print settings should be ‘fit to page size’ or ‘fit to printable area’ or similar. Problems? See our guide: https://atg.news/2zaGmwp 7 1 -2 0 2 1 9 1 ISSUE 2507 | antiquestradegazette.com | 4 September 2021 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50 S E E R 50years D koopman rare art V A I R N T antiques trade G T H E KOOPMAN (see Client Templates for issue versions) THE ART M ARKET WEEKLY 12 Dover Street, W1S 4LL [email protected] | www.koopman.art | +44 (0)20 7242 7624 Robert Brooks: the boss who built the Bonhams brand by Alex Capon in 2010. He always looked up to his father, naming the new lecture theatre at Bonhams Former chairman of New Bond Street in his honour Bonhams Robert Brooks in 2005. has died aged 64 after a He opposed guarantees Among the highlights two-year battle with (although did occasionally use of the Alan Blakeman cancer. them later on) and challenged collection to be sold Having started his own Sotheby’s and Christie’s to by BBR Auctions on classic car saleroom, Brooks follow Bonhams’ example of September 11 is this Auctioneers, at the age of 33, introducing separate client shop display pot lid. he bought Bonhams 11 years accounts for vendors’ funds. Blakeman was pictured with later before merging it with Never lacking a competitive it on the cover of the programme Phillips in 2001. He streak, Brooks had left school produced for the first UK Summer subsequently expanded the as a teenager to briefly become National fair in 1985 (above). -

Welcome Pack

Welcome to St George’s Court We wish you a pleasant stay and hope you find the following pages of information useful. If you would prefer fresh milk rather than the milk portions, please ask at the house If you require any extra pillows, please just ask. You will find spare blankets in each room in case you require them. You will also find situated in a drawer a hairdryer a radio alarm clock and rechargeable torch. If you require the use of an iron and ironing board please ask at the house. Breakfast is served between 8:30am and 9:00am. No allowance will be made for meals not taken. We would like to remind you that all our rooms are no smoking. We kindly request that you vacate your room between the hours of 10:30am and 1:30pm to allow us to clean. If you are unable to do so we will be happy just to top up your tea tray on request. On the day of departure we request that you vacate your room by 10:30am. All vehicles are parked at the owner’s risk and we do not accept any responsibility for the loss or damage of them. Please park to the rear of the building unless you require any assistance. We kindly request that when you return on an evening you are as quiet as possible for the comfort of all our guests. The proprietors cannot accept responsibility for the loss or damage of guest’s property unless handed in for safe custody. -

UK TV Outside Broadcast Fibre Connected Venues

UK TV Outside Broadcast fibre connected venues From UK venues to a North of England Arenas Middlesbrough FC Blackpool Winter Gardens Newcastle United FC worldwide audience Sheffield United FC Echo Arena Liverpool Manchester Arena Wigan Athletic FC Football and training Horse racing grounds Aintree Racecourse Barnfield (Burnley FC) Beverley Racecourse Burnley FC Carlisle Racecourse Carrington Complex Cartmel Racecourse (Man Utd FC) Catterick Racecourse Darsley Park (Newcastle FC) Chester Racecourse Etihad Complex (Man City FC) Haydock Racecourse Scotland Everton FC Market Rasen Racecourse Arenas St Johnstone FC Finch Farm (Everton FC) Pontefract Racecourse Hallam FM Academy Redcar Racecourse SEC Centre St Mirren FC (Sheff Utd FC) Thirsk Racecourse Football and Horse racing Leeds United FC Wetherby Racecourse training grounds Ayr Racecourse Leigh Sports Village York Racecourse Aberdeen FC Hamilton Racecourse Liverpool FC Celtic FC Kelso Racecourse Manchester City FC Rugby AJ Bell Stadium Dundee United FC Musselburgh Manchester United FC Leigh Sports Village Hamilton Academical Racecourse Melwood Training Ground FC Perth Racecourse (Liverpool FC) Newcastle Falcons Hibernian FC Rugby Kilmarnock FC Scotstoun Stadium Livingstone FC Motherwell FC Stadiums Rangers FC Hampden Stadium Ross County FC Murrayfield Stadium Midlands and East of England Arenas West Bromwich Albion FC Birmingham NEC Wolverhampton Coventry Ricoh Arena Wanderers FC Wales and Wolverhampton Civic Hall Horse racing Football and Cheltenham Racecourse training grounds Gloucester -

RPRA Rule Book 2020

THE OFFICIAL RULES 2020 Page 2 ROYAL PIGEON RACING ASSOCIATION OFFICERS 2020 President: Mr D. Bridges (3rd year) Vice-Presidents: Mr G. Cockshott (3rd year), Mr P. Hammond (2nd year), Mr J. Waters (2nd year) Trustees: Mr L. Blacklock, Mr D. Higgins, Mr R. Shirley PRESIDENT EX-OFFICIO MEMBER OF ALL COMMITTEES FInAnce & generAl PurPOses emergency & rules APPeAls clOcK, rIng & weATHer lIBerATIOn sITe L Blacklock – CA L Blacklock – CA L Blacklock – CA D Bridges – DY (Chair) D Bridges – DY (Chair) D Bridges – DY S Briggs – IR S Briggs – IR C O’Hare – IR J Dodd – EM J Heague – WE G Cockshott – NE J Gladwin – LN A Ewart – EM J Dodd – EM P Hammond – WM N Darby – WM R Harris – SO D Headon – DC J Gladwin – LN D Headon – DC D Higgins – NE D Headon – DC T Gardner – WS T Gardner – WS D Higgins – NE P Hammond – WM R Harris – SO C Gordon – NE S Mellor – NW S Mellor – NW R Shirley – SW T Gardner – WS E Hendrie – LN R Harris – SO J Waters – WE R Shirley – SW S Mellor – NW J Waters – WE (Chair) R Shirley – SW FuTure OF THe sPOrT OlymPIAD D Bridges – DY (Chair) BrITIsH HOmIng wOrlD L Blacklock – CA G Cockshott – NE L Blacklock – CA D Bridges – DY (Chair) D Higgins – NE D Bridges – DY (Chair) G Cockshott – NE J Heague – WE S Briggs – IR R Harris – SO J Dodd – EM J Waters – WE D Headon – DC P Hammond- WM J Dodd – EM R Harris – SO P Hammond – WM R Shirley – SW J Waters – WE D Headon – DC J Gladwin – LN E Hendrie – LN G Cockshott – NE T Gardner – WS R Harris – SO cOnFeDerATIOn OF lOng D Headon – DC DIsTAnce rAcIng PIgeOn T Gardner – WS PerFOrmAnce enHAncIng Drugs S Mellor – NW unIOns OF gB & IrelAnD R Shirley – SW D Bridges – DY D Bridges – DY (Chair) I Evans – CEO J Waters – WE J. -

Newsletter Update

www.racecourseassociation.co.uk December 2018 December updatenewsletter CONTENTS Welcome 03 Raceday Experience Group 05 5 Did You Know ... 07 Racecourse Grounstaff Courses 07 Badges & Pass 2018 08 Racegoers Club 10 Five Minutes of Fame 12 Racehorse Owners Association 13 RaceTech 14 GBRI 15 Racing Foundation 16 Racing to School 17 Racing Together 18 The Thoroughbred Club 18 Thoroughbred Breeders Assoc. 19 Careers in Racing 20 Watt Fences 22 Duralock 23 Sporting Edge 24 Diary Dates / Contributors / 25 Staff Contact List 11 14 18 2 | RCA Update Newsletter 2018 Back to content page WELCOMEWords by Paul Swain presentation this week from our Our December Update is packed full Racing Assistant Megan Bouwman. of content to keep you going through Megan has made the transition from your Christmas dinner until the Queen’s stable life to office life over the past speech. We check-in with the Raceday few years, starting with the BHA Experience Group after their December Graduate Development Programme meeting at Musselburgh, the latest On and progressing to the Northern Racing Track looks at our recent survey with College and now the RCA via stints the NTF around trainers’ motivations with Harry Fry and Clive Cox. Megan’s to run their horses and we sit down with enthusiasm for all things racing is clear Doncaster’s new Executive Director to anyone who meets her and to hear Russell Smith who is probably the first-hand from someone who has been biggest Hibs fan you’ll find in Yorkshire. involved with successful training yards Finally, a big congratulations to all at and the care, attention and teamwork Chester and Bangor who were recently required to train thoroughbreds was crowned large and small racecourses inspiring for the full team. -

Lovesome Hill Farm

Lovesome Hill Farm Lovesome Hill Farm Contact Details: N*o+rthal0l1e2r3t4o5n6 N*o+rth Y0o1r2k3s4h5i6r7e8 D*L+6 2PB0 England Lovesome Hill Farm, Guest House, B&B in Northallerton,North Yorkshire.For more information on Lovesome Hill Farm,Northallerton Guest House, B&B please send an email enquiry to the owner. Facilities: Room Details: © 2021 LovetoEscape.com - Brochure created: 27 September 2021 Lovesome Hill Farm Recommended Attractions 1. Aerial Extreme in North Yorkshire Childrens Attractions, Walking and Climbing A thrilling Adventure Ropes Course set on the grounds of the Kirklington, DL8 2LS, North Yorkshire, Camphill Estate in Kirklington North Yorkshire England 2. Outdoor Experiences in North Yorkshire Childrens Attractions, Cycling and Mountain Bikes, Shooting and Fishing, Guided Tours and Day Trips We offer Outdoor Experiences such as Off Road Quads and Felixkirk Thirsk, YO7 2DP, North Defenders Shooting and Fishing Segway Gliding in North Yorksire. Yorkshire, England Exclusive custom-built packages to provide a truly memorable experience. We also cater for kids. Phone: 01845 537 766 3. Lightwater Valley Family Theme Park North Yorkshire Festivals and Events, Lochs Lakes and Waterfalls, Childrens Attractions, Theme Parks A Theme Park with over 40 rides and attractions for thrill seekers of North Stainley, Ripon, HG4 3HT, North all ages including Europe's longest roller coaster-The Yorkshire, England Ultimate.Located near Ripon in North Yorkshire. Phone: 0871 720 0011 4. Ripon Races Yorkshire Racecourse Sports Venues, Horse Racing Ripon Racecourse recently won Best Small Racecourse in the North; The Racecourse, Boroughbridge Road, a fitting accolade and just description for what is a beautiful and Ripon, HG4 1UG, North Yorkshire, unique racecourse. -

British Jump Pattern and Listed Races 2019/2020

BritishBritish JumpJump PatternPattern andand ListedListed RacesRaces 2019/20202019/2020 The Jump Pattern and Listed Race Book is an official publication of the British Horseracing Authority Limited. Registered Office: 75 High Holborn, London, WC1V 6LS. Registered Number 2813358 England. Telephone: 020 7152 0000 Fax: 020 7152 0001. Email: [email protected] PUBLISHED BY THE BRITISH HORSERACING AUTHORITY ©BRITISH HORSERACING AUTHORITY LTD., 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording or re-publication without the written permission of the British Horseracing Authority to whom such application for permission should be addressed. Such written permission must also be obtained if any part hereof is stored on a retrieval system of any nature. HANDICAPS AND OTHER RATING RELATED RACES HANDICAP RATING FOR QUALIFICATION Before making entries for Handicaps and other Rating Related races, reference must be made to the qualifying Rating Lists published on the Information area of the British Horseracing Authority Racing Administration Service Internet site each Tuesday. These ratings will apply for qualification purposes for races closing on the Tuesday of publication through to the following Monday. Amendments to these qualifying ratings will also be published, for information, on the Information area of the Racing Administration Internet site. HANDICAPS WITH SPLIT ENTRY STAKE FEES For those Handicap races which have a split entry stake fee dependent on the Handicap rating of the horse, i.e. £xx stake if the horse is rated aa or higher, or £yy stake if the horse is rated bb or lower with £zz extra if the horse is declared to run The relevant stake fee shall be determined by the Handicap rating used to calculate the weight for each horse entered in the race in question, and not by the published qualifying rating, if any.