Hilmar Cheese Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visitor Center in California Hilmar Ingredients Our Facilities Hilmar

Hilmar Cheese Company Hilmar Ingredients Our Facilities Hilmar Cheese Company Catering Visitor Center in California Opened in 1998, our Visitor Center and Café are the perfect halfway stop between San Francisco and HEADQUARTERS & INNOVATION CENTER Hilmar Cheese Company Catering, available in California’s Central Valley, is a premier event planner and caterer. Our Yosemite or any trip through the Central Valley. HILMAR, CALIFORNIA extensive menu is sure to please all palates and our elegant presentation complements any celebration or meeting. We Designated by the US TOUR Green Building Council as orchestrate events in our beautiful banquet facility, with its a LEED Platinum Building landscaped park and flower-bordered waterfall perfect for photos. Free self-guided tours and guided tours for schools, tour groups and families: Hilmar Cheese Company specializes in the production of natural A division of Hilmar Cheese Company, Hilmar Ingredients delivers powered partially by solar. • Fun, hands-on exhibits cheeses used by private store labels, national brands and the promise of dairy – whey protein, lactose (milk sugar) and milk • “Edutaining” mooovie food-service companies across America and the world. Cheese is powders. These are sought-after ingredients • Ice cream making and packaged in 40 lb. (20 kg.) blocks or 640 lb. (300 kg.) crates. for many of the world’s foods and beverages. cheesemaking tours Rare among large manufacturing Whey protein, a highly refined HILMAR MANUFACTURING SITE Check our tour schedule at: www.hilmarcheese.com. sites, we have the ability to and updated version of the whey produce a range of cheeses in in Miss Muffet’s curds and whey, HILMAR, CALIFORNIA TASTE large volumes, as well as the provides the perfect blend of Original operation Complimentary tastes of: flexibility to adjust quickly to protein nutrition needed for good located in California’s our customers’ changing needs. -

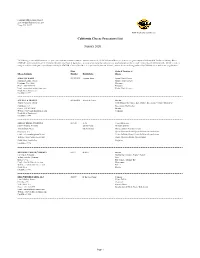

California Cheese Processors List January 2020

California Milk Advisory Board 2316 Orchard Parkway Suite 200 Tracy, CA 95377 www.RealCaliforniaMilk.com California Cheese Processors List January 2020 The following is a list of California cheese processors (and other contacts) who are authorized to use the Real California Milk® seal. Seal use is regulated by the California Milk Producers Advisory Board (CMPAB), an instrumentality of the California Department of Food & Agriculture, as a way of certifying that consumers are purchasing natural cheese made exclusively with California milk. All cheesemakers using the seal have undergone a special inspection by the CMPAB. Cheeses listed here are representative, but not inclusive, as new cheeses are being produced by California cheesemakers on a regular basis. Plant Styles & Varieties of Cheese Company Number Brand Name Cheese ANDANTE DAIRY 06-00132M Andante Dairy Largo (Triple Cream) Soyoung Scanlan, Owner Minuet (Triple Cream) Petaluma, CA 94952 Nocturne Phone: 707-769-1379 Pianoforte Email: [email protected] Picolo (Triple Cream) Retail Sales, Foodservice Established 1999 ANGELO & FRANCO 06-00004M Angelo & Franco Burrata Angelo Carcaclia, Owner Fresh Mozzarella (Classic Ball, Ovaline, Bocconcini, Ciliegine Marinated) Hawthorne, CA Bocconcini (Mozzarella) Phone: 310-263-0506 Ricotta Website: www.angeloandfranco.com Scamorza Retail Sales, Foodservice Established 1944 ARIZA CHEESE COMPANY 06-3721 Ariza Crema Mexicana Pablo Gonzalez, President Quesos Ariza Jocoque (Labneh) 7602 Jackson Street Quesos Cotija Monterey Jack (Premium Grade) -

Hilmarcheesebrochure.Pdf

Visitor Center in California We’re on Your Way… The Visitor Center opened in 1998. Each year, our HILMAR, CALIFORNIA staff guides thousands of 9001 North Lander Avenue students and tour groups Hilmar, CA 95324 through the cheesemaking 800.577.5772 process and hands-on Directions exhibits, while sharing the From Highway 99 (at Turlock), go 4 miles south on Lander importance of sustainable Avenue (Hwy 165). Look for the Visitor Center on the right. agriculture and resource management. From I-5 (at Los Banos), go north on Hwy 165 through Los Banos, then 35 miles more to Hilmar. Look for the Visitor Tour Center on the left. FREE self-guided tours and guided tours for schools, tour Sacramento groups and families: 580 99 Modesto • Fun, hands-on exhibits Hilmar Cheese Co. Catering San Francisco Turlock • “Edutaining” mooovie Hilmar Cheese Company Catering is the Central Valley’s 5 • Ice cream-making and premier event planner and caterer. Our extensive menu Yosemite cheesemaking tours is sure to please all palates, and our elegant presentation Hilmar 140 Merced Check our tour schedule at: complements any event. We orchestrate events off-site or 165 www.hilmarcheese.com in our beautiful banquet facility, with its landscaped park, picnic area and flower-bordered waterfall. Taste Our banquet facility is ideal for: Hilmar Cheese Company Visitor Center Welcome Complimentary tasting of: Open daily; please call 800.577.5772 for hours TO HILMAR CHEESE COMPANY • Hilmar Cheeses • Wedding Receptions • Baby Showers • Bridal Showers • Corporate Holiday Parties Closed New Year’s Day, Easter, Memorial Day, Independence • Local Artisan Cheeses Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving and Christmas • Gourmet Foods • Anniversaries • Convention Groups • “Squeakers” — cheese curds • Class Reunions • More… DALHART, TEXAS made fresh every day The Visitor Center’s banquet-area amenities include: 12400 Highway 385 The Hilmar Cheese Company brand is available for sale only • Dance Floor P.O. -

Statement Hilmar Cheese Company, Inc

Statement of Patricia D. Stroup on behalf of Hilmar Cheese Company, Inc. at the United States Department of Agriculture Emergency Hearing on Class III and IV Price Formulas in all Federal Milk Marketing Orders at Alexandria, Virginia, commencing January 24, 2006 My name is Patricia Stroup. I am the Director of Dairy Policy and Producer Services of Hilmar Cheese Company, Inc., whom I represent today at this hearing. In my role at Hilmar, I am responsible for milk and milk ingredients procurement from individual dairy farms, cooperatives and proprietary handlers. I have been with Hilmar Cheese since 1997. Prior to that, I held positions with Maryland and Virginia Milk Producers Cooperative in Reston, Va., and Eastern Milk ProducersIMilk Marketing Inc in Syracuse, N.Y., and Cleveland, Ohio, and was a dairy producer, myself, in Pennsylvania. I hold an M.B.A. from Purdue University and an undergraduate degree with a cognate in Dairy Science from Virginia Tech. I developed this testimony in cooperation with Hilmar Cheese Company staff and present it today with authorization from the Chief Executive Officer and owners of Hilmar Cheese Company. Hilmar Cheese Company operates a cheese and whey products facility in Hilmar, California. This plant currently processes approximately 12 million pounds of milk per day into American-style cheeses such as cheddar and Monterey Jack. In addition to our California facility, Hilmar Cheese Company will be building another American-style- cheese plant in Dalhart, Texas, with plans to begin operations in the fall of 2007. We plan for the Texas plant to eventually process 9.5 million pounds of milk per day. -

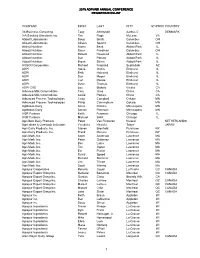

Final List.Xlsx

2015 ADPI/ABI ANNUAL CONFERENCE REGISTRATION LIST COMPANY FIRST LAST CITY ST/PROV COUNTRY 3A Business Consulting Tage Affertsholt Aarhus C DENMARK 3-A Sanitary Standards Inc. Tim Rugh McLean VA Abbott Laboratories Doug Smith Columbus OH Abbott Laboratories Allison Specht Columbus OH Abbott Nutrition Aaron Beak Abbott Park IL Abbott Nutrition Dana Friedman Columbus OH Abbott Nutrition Robert Hoaglund Abbott Park IL Abbott Nutrition Dan Potratz Abbott Park IL Abbott Nutrition Bryan Stirrat Abbott Park IL ACSON Corporation Richard Freeland Scottsdale AZ ADPI Steve Griffin Elmhurst IL ADPI Beth Holcomb Elmhurst IL ADPI Dan Meyer Elmhurst IL ADPI Carl Roode Elmhurst IL ADPI Dave Thomas Elmhurst IL ADPI COE Lee Blakely Visalia CA Advance Milk Commodities Tom Groe Chino CA Advance Milk Commodities Leslie Perkins Chino CA Advanced Process Technologies Craig Campbell Cokato MN Advanced Process Technologies Philip Cunningham Cokato MN AgMotion Dairy Steve Perkins Minneapolis MN AgMotion Dairy Steven Peterson Minneapolis MN AGR Partners Keith Freeman Chicago IL AGR Partners Michael Solot Chicago IL Agri-Best Dairy Products Peter Van Pinxteren Nuland NETHERLANDS Agriculture & Livestock Industries Yasuhisa Hiraishi Tokyo JAPAN Agri-Dairy Products, Inc. Steven Bronfield Purchase NY Agri-Dairy Products, Inc. Frank Reeves Purchase NY Agri-Mark, Inc. Scott Anderson Lawrence MA Agri-Mark, Inc. Peter Gutierrez Lawrence MA Agri-Mark, Inc. Ben Laine Lawrence MA Agri-Mark, Inc. Tim Opper Lawrence MA Agri-Mark, Inc. Ed Pcolar Lawrence MA Agri-Mark, Inc. David Speed Lawrence MA Agri-Mark, Inc. Richard Stammer Lawrence MA Agri-Mark, Inc. Jim Tringe Lawrence MA Agri-Mark, Inc. Scott Werme Lawrence MA Agropur Cooperative Reneck Cayen La Prairie QC CANADA Agropur Export Group Inc. -

Our Commitment to Sustainability Welcome to Hilmar Cheese Company

2 012 Our Commitment to Sustainability Welcome to Hilmar Cheese Company Making cheese and whey products that contribute nutrition, enjoyment and value to people’s lives. Owned by 11 local Jersey cow dairy farming families, Hilmar Cheese Company, Inc. produces cheese and whey products that nourish more than 20 million people worldwide each day. From the shredded cheese in tacos to the whey protein and lactose in infant formula, Hilmar Cheese Company and our division, Hilmar Ingredients, deliver the promise of dairy to consumers around the world. About Our Cover Contents Reflecting our commitment to the environment, The Company the community and our employees Letter from CEO 3 $10,000 Donated Our History 4 to Snack Pak 4 Kids Our Mission 5 to help them provide Goals and Progress 6 weekend meals for hungry students www.snackpak4kids.org Environmental Stewardship 8 100% of Our Employees 10 Reclaimed Economic Value 12 Water Community Engagement 14 is recycled and reused on our facilities and 40 Employees 31 Students for irrigation were promoted from received college within the company scholarships from Hilmar Cheese Company 100% of the This report is based on the methodology outlined by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), a nonprofit Dairy Farm Families organization that develops and publishes guidelines who ship their milk directly to Hilmar Cheese for reporting on sustainability performance. Company participate in the Farmers Assuring More information on the GRI can be found Responsible ManagementTM animal care program at www.globalreporting.org. The information presented reflects data collected for 2012 .....2 A Letter from Our CEO We appreciate you – a customer, business partner, employee, community member or consumer – taking an interest in learning a bit more about Hilmar Cheese Company, Inc. -

APPLY NOW! of Wholesome Dairy Products That Contribute to the Success of All Stakeholders

PROFESSIONAL CAREER OPPORTUNITIES YOU BELONG HERE At Hilmar Cheese Company we improve lives around the world by being a leading producer APPLY NOW! of wholesome dairy products that contribute to the success of all stakeholders. hilmarcheese.com Hilmar Cheese Company, Inc. is that rare blend of a people- oriented company and an innovator. Work for our employees is unique – delivering both business and personal growth. We maintain our edge through professional staff members who excel at collaboration, adaptability, diligence and communication. As part of our team, you can tackle challenging problems until they become discoveries and guide ideas from concept to market. Contribute your expertise and help us design and create dairy products for better human health. X Food Processing X Corporate Services X Engineering X Research and Applications X Plant Management X Information Technology X Business Operations (SAP) FOUR LOCATIONS X Headquarters & Innovation Center, HILMAR, CA X Hilmar Manufacturing Site, HILMAR, CA X Turlock Manufacturing Site , TURLOCK, CA X Dalhart Manufacturing Site , DALHART, TX Founded in 1984 by entrepreneurial dairy farmers, Hilmar Cheese Company and our division Hilmar Ingredients have APPLY NOW! grown exponentially. Our original location and headquarters hilmarcheese.com is now the world’s largest single-site cheese and whey products manufacturing facility, and our second facility, built in 2007, FOLLOW US: is nearly equivalent in size. A third facility producing milk powders will be completed Q4 2015. Our products – cheese, whey protein, lactose and milk powder, are used by national and international brand companies, private label and foodservice in more than 50 countries. At Hilmar Cheese Company we take seriously our responsibility to manage our business in a manner that balances economic, social and environmental sustainability. -

At Hilmar Cheese Company We Improve Lives Around the World by Being a Leading Producer of Wholesome Dairy Products That Contribute to the Success of All Stakeholders

OUR COMMITMENT TO SUSTAINABILITY 2 019 At Hilmar Cheese Company we improve lives around the world by being a leading producer of wholesome dairy products that contribute to the success of all stakeholders. WELCOME TO HILMAR CHEESE COMPANY Making dairy products that contribute nutrition, enjoyment and value to people’s lives. Hilmar Cheese Company, Inc., and its division, Hilmar Ingredients, serve customers in more than 50 countries. State-of-the-art production facilities in California and Texas convert high-quality milk received from local, independent dairy farms into a variety of nutritious cheeses and whey ingredients. Committed to continuous improvement, innovation and sustainability, Hilmar Cheese Company strives to make products that benefit all involved – from our customers and our suppliers to our employees and communities. Together, we deliver the promise of dairy. HIGHLIGHTS OF 2019 CONTENTS These highlights reflect our commitment to the The Company environment, the community and our employees Letter From CEO 3 Our History 4 Record number of students participated Our Purpose and Culture 5 in our educational programs, more than 17,000 Goals and Report 6 Environmental Stewardship 8 Our Employees 10 100% of our reclaimed water is recycled Economic Value 12 and reused, most for crop irrigation On the Farm 13 Community Engagement 14 20th annual holiday canned food drive awards the Dalhart Milk Receiving team SCOPE OF THIS REPORT as the Hunger Heroes This report for calendar year 2019 is our tenth annual report. It reflects the total company efforts from our Dalhart, Texas, manufacturing site; and Hilmar, California, manufacturing site and Headquarters & Innovation Center. -

Our Commitment to Sustainability

2 014 Our Commitment to Sustainability We deliver the promise of dairy.TM WELCOME TO HILMAR CHEESE COMPANY Making cheese and whey products that contribute nutrition, enjoyment and value to people’s lives. Founded by 12 local dairy farming families and still privately held by those families, Hilmar Cheese Company, Inc. produces cheese and whey products that nourish more than 20 million people worldwide each day. From the shredded cheese in tacos to the whey protein and lactose in infant formula, Hilmar Cheese Company and our division, Hilmar Ingredients, deliver the promise of dairy to consumers around the world. ABOUT OUR COVER CONTENTS Reflecting our commitment to the environment, The Company the community and our employees Letter from CEO 3 Our History 4 LEED Platinum® Dedication Our Mission 5 with the California Department of Food Goals and Progress 6 Agriculture Secretary, Karen Ross Environmental Stewardship 8 Employees 10 100% of Our Economic Value 12 Reclaimed Water On the Farm 13 Community Engagement 14 is recycled and reused, most 100% of the for crop irrigation Dairy Farm SCOPE OF THIS REPORT Families This report for calendar year 2014 is our fifth annual report. It reflects total company efforts from our Dalhart, Texas, manufacturing site; and Hilmar, who have supply California, manufacturing site and Headquarters & Innovation Center. agreements with Hilmar Cheese Company are This report follows the industry-adopted Stewardship and Sustainability Guide certified participants for U.S. Dairy (www.usdairy.com), a voluntary framework for tracking and in the Farmers $42,000 29 Students communicating progress. It also incorporates the methodology outlined by the Assuring Responsible Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), a nonprofit organization that develops and raised for American received college ManagementTM animal publishes guidelines for reporting on sustainability performance. -

Internship Program Summer 2016

INTERNSHIP PROGRAM SUMMER 2016 Hilmar Cheese Company, Inc. provides a variety of paid, project-based collegiate internships in various departments including: ENGINEERING · PRODUCTION RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT YOU BELONG HERE At Hilmar Cheese Company we improve lives around the world by being a leading producer of wholesome dairy products that contribute to the success of all stakeholders. REQUIREMENTS APPLY NOW! X Willing to learn, team- X Have completed hilmarcheese.com oriented, strong work sophomore year with ethic, demonstrates a major relevant to the leadership qualities department and project APPLICATION PERIOD: X Be available to work full- X Legal right to work September – December 2015 time during the program in the United States term – 8-12 weeks FOUR LOCATIONS X Headquarters & Innovation Center, HILMAR, CA X Hilmar Manufacturing Site, HILMAR, CA X Turlock Manufacturing Site , TURLOCK, CA X Dalhart Manufacturing Site , DALHART, TX NEW GRADUATE CAREER OPPORTUNITIES PLANT OPERATIONS ENGINEERS MANAGEMENT Our Engineering team seeks engineers – experienced Plant Operations is a common starting ground for new and new – interested in a fast-paced highly progressive college graduates and seasoned production workers environment. PROCESS ENGINEERS work closely with alike. Our PRODUCTION SUPERVISORS lead the daily plant operations – focusing on the optimum, most cost- operations and develop highly skilled plant operators. effective methods of manufacturing our products. Incumbents in this position start out strong by participating in a six-week training program – spending time in each QUALITY SERVICES plant area to gain an understanding of our entire Our Quality Services team is responsible for coordinating, operations. At the end of the training program supervisors maintaining, and improving the corporate-wide quality are placed in various plants, where departmental management systems and programs. -

Our Commitment to Sustainability

OUR COMMITMENT TO SUSTAINABILITY 2 015 At Hilmar Cheese Company we improve lives around the world by being a leading producer of wholesome dairy products that contribute to the success of all stakeholders. WELCOME TO HILMAR CHEESE COMPANY Making dairy products that contribute nutrition, enjoyment and value to people’s lives. Hilmar Cheese Company, Inc. and its division, Hilmar Ingredients, serve customers in more than 50 countries. State-of-the-art production facilities in California and Texas convert high-quality milk received from local, independent dairy farms into a variety of nutritious cheese, whey ingredients and milk powders. Committed to continuous improvement, innovation and sustainability, Hilmar Cheese Company strives to make products that benefit all involved from our customers and our suppliers to our employees and communities. Together, we deliver the promise of dairy. HIGHLIGHTS OF 2015 CONTENTS Reflecting our commitment to the environment, The Company the community and our employees Letter from CEO 3 Our History 4 Our Purpose & Culture 5 Goals and Progress 6 Received the 2015 Outstanding Dairy Processing Environmental Stewardship 8 & Manufacturing Sustainability award from Innovation Employees 10 Center for U.S. Dairy Economic Value 12 Completed construction on third On the Farm 13 manufacturing site – milk powder Community Engagement 14 facility, Turlock, California SCOPE OF THIS REPORT 100% of our reclaimed water This report for calendar year 2015 is our sixth annual report. It reflects total is recycled and reused, most for company efforts from our Dalhart, Texas, manufacturing site; and Hilmar, crop irrigation California, manufacturing site and Headquarters & Innovation Center. This report follows the industry-adopted Stewardship and Sustainability Guide for U.S. -

Dairy Hearing Hilmar Cheese.Pdf

USDA OALJ/OHC "l,.,, l'.'fl J ·1 'H 1n: 06 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE:'. ·J ·. ".,.j f\ "' BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF AGRICULTURE Re: Proposal to Establish a Federal Milk Docket No. A0-15-0071; Marketing Order for California AMS-DA-14-0095 Hearing in Fresno, California, September- November 2015 Post-Hearing Brief for Hilmar Cheese Company John H. Vetne, Consultant PO Box 15 New Portland, ME 04961 Tel: 207-628-2005 James De J ong Dairy Policy and Economic Analyst Hilmar Cheese Company PO Box 910 Hilmar, CA 95324 Tel: 209-667-6076 Alan Zolin, Consultant Zolin International LLC 230 Elmore St Park Ridge, IL 60068 Tel: 847-692-5852 March 28, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. Background for the Proposed California Federal Milk Marketing Order 2 II. Proponents of a Federal FMMO for California Have the Burden of Proof, and Have Failed to Meet That Burden. 4 III. Proposed Findings of Fact. 6 A The value of milk and dairy products, like any commodity, varies by location. This is a function of supply, demand, and transportation 00~. 6 B. The commodity value of cheddar cheese is lower in California than in FMMO markets. 10 C. The effect of geographically variable value of cheddar cheese prices on make allowances, manufacturer return on investment, and ability to pay for milk at U.S. NASS-NDPSR Class III price averages. 13 D. The commodity value ofNFDM and butter is lower in California than in other markets. This adversely affects manufacturer return on investment and ability to pay for milk in California at U.S.