Transfiguring Form: the Poetics of Self, Contradiction and Nonsense

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Mystics Hear the Song by W

20 Copyright © 2005 The Center for Christian Ethics How Mystics Hear the Song BY W. DENNIS TUCKER, JR. Mystics illustrate the power of the Song of Songs to shape our understanding of life with God. Can our lan- guishing love be transformed into radical eros—a deep yearning that knows only the language of intimate com- munion, the song of the Bridegroom and his Bride? he language of the Song of Songs—so replete with sexual imagery and not so subtle innuendos that it leaves modern readers struggling Twith the text’s value (much less its status as Scripture)—proved theo- logically rich for the patristic and medieval interpreters of the book. Rather than avoiding the difficult imagery present in the Song, they deemed it to be suggestive for a spiritual reading of the biblical text. In the Middle Ages, more “commentaries” were written on the Song of Songs than any other book in the Old Testament. Some thirty works were completed on the Song in the twelfth century alone.1 This tells us some- thing about the medieval method of exegesis. Following the lead of earlier interpreters, the medieval exegetes believed the Bible had spiritual mean- ing as well as a literal meaning. From this they developed a method of in- terpretation to uncover the “fourfold meaning of Scripture”: the literal, the allegorical, the moral, and the mystical.2 Medieval interpreters pressed be- yond the literal meaning to discover additional levels of meaning. A MONASTIC APPROACH Before we look at how three great mystics in the Christian tradition— Bernard of Clairvaux, Teresa of Avila, and John of the Cross—made use of the Song, let’s consider a larger issue: Why did the Song generate such per- sonally intense reflections in the works of the mystics? The form and focus of “monastic commentaries” in the medieval period was well suited for a spiritual reading of the Song. -

The Virgin and the Basilisk - a Study of Medieval Women and Their Social Roles in Iacopone Da Todi’S (1230/36-1306) Laude.1

THE VIRGIN AND THE BASILISK - A STUDY OF MEDIEVAL WOMEN AND THEIR SOCIAL ROLES IN IACOPONE DA TODI’S (1230/36-1306) LAUDE.1 Annamaria Laviola Lund University During his lifetime, the Franciscan Iacopone da Todi (1230/36-1306) wrote a number of poems now known under the collective name of Laude. Influenced by different literary styles, such as Sicilian-Tuscan and differentiating itself from the Franciscan literary production of its time, Iacopone’s Laude discuss both religious and secular matters.2 This article is a study of the collection and the information for the modern reader about urban Italian women and their social roles in the thirteenth century, focusing on the following research questions: What are women’s different social roles according to the Laude? How are these roles constructed and described? In what ways does a study of the Laude help the historian to understand the ambivalent relation(s) within and between women’s roles in medieval society? Historiography Italian scholars writing during the second half of the twentieth century studied the Laude in order to answer questions of theological and literary character. Alvaro Bizziccari’s article on the concept of mystical love in the Laude, Franco Mancini’s focus on the variety of themes discussed by Iacopone and Elena Landoni’s study of the different literary styles that can be found in the Laude are but a few examples of this tendency.3 Even though much of the (Italian) scholarly interest for Iacopone da Todi has focused on subjects related to theology and literature, in recent years both Italian and international scholars have started to analyse other aspects of the texts. -

CONCLUSION in a Rather Famous Lauda by the Franciscan Poet

CONCLUSION In a rather famous lauda by the Franciscan poet Jacopo Benedetti (c. 1236–1306), better known as Jacopone (Big John) da Todi, he assails his brethren in Paris who he says “demolish Assisi stone by stone.” “That’s the way it is, not a shred left of the spirit of the Rule! […] With all their theol- ogy they’ve led the Order down a crooked path.”1 It is a complaint to which Jacopone returns many times in his writing.2 “Assisi” in this case seems to reflect the spiritual or, as David Burr says, a rigorist’s view of Franciscan virtue, which was basically centered on the ideals of evangelical poverty, charity, and penance. “Paris,” on the other hand, represents the arrogance of educated Friars—“an elite with special status and privileges” who looked down on their brothers.3 The conflict of the 1290s, when most of Jacopone’s laude were written, sing of struggles within the Order that go back to the 1220s, to a time when the friars were first grappling with their identity; and, as I have shown, this involved their chanting and preaching—the two aspects of the Franciscan mission of music that I have examined in this study. In Chapter One we saw that while the Regula non Bullata (Earlier Rule) of 1221 required all Franciscan friars to celebrate the Divine Offices, albeit in distinctive forms, the Regula Bullata (Later Rule) of 1223 privileged the clerical brothers as singers of the rite according to the Roman church.4 The Earlier Rule would not exclude the lay brothers from preaching, so long as they did not preach against the rites and practices of the Church and had the permission of the minister.5 But this was emended in the Later Rule, making preaching incumbent only on friars who had been properly examined, approved, and had “the office of preacher […] 1 “Tale qual è, tal è;/ non ci è relïone./ Mal vedemo Parisi,/ che àne destrutt’Asisi:/ co la lor lettoria messo l’ò en mala via.” [That’s the way it is—not a shred left of the spirit of the Rule! In sorrow and grief I see Paris demolish Assisi, stone by stone. -

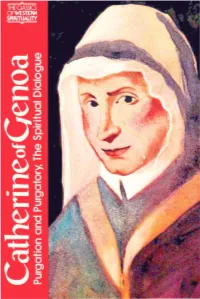

CATHERINE of GENOA-PURGATION and PURGATORY, the SPIRI TUAL DIALOGUE Translation and Notes by Serge Hughes Introduction by Benedict J

TI-ECLASSICS a:wESTEP.N SPIPlTUAIJTY i'lUBRi'lRY OF THEGREfiT SPIRITUi'lL Mi'lSTERS ··.. wbile otfui'ffKS h;·I�Jmas tJnd ;·oxiJ I:JOI'I!e be n plenli/111, books on \�stern mystics ucre-.trlfl o1re -bard /(I find'' ''Tbe Ptwlist Press hils just publisbed · an ambitious suies I hot sbu111d lnlp remedy this Jituation." Psychol�y li:x.Jay CATHERINE OF GENOA-PURGATION AND PURGATORY, THE SPIRI TUAL DIALOGUE translation and notes by Serge Hughes introduction by Benedict j. Grocschel. O.F.M. Cap. preface by Catherine de Hueck Doherty '.'-\1/tbat I /ltJt'e saki is notbinx Cllmf'dretltowbat lfeeluitbin• , t/Hu iJnesudwrresponden�.· :e /J/ hwe l�t•twec.'" Gtul and Jbe .\ou/; for u·ben Gfltlsees /be Srml pure llS it iJ in its orixins, lie Ill/(.� ,1( it ll'tlb ,, xlcmc.:c.•. drau·s it llrYIbitMIJ it to Himself u-ilh a fiery lfll•e u·hich by illt'lf cout.lunnibilult' tbe immorttJI SmJ/." Catherine of Genoa (}4-17-15101 Catherine, who lived for 60 years and died early in the 16th century. leads the modern reader directly to the more significant issues of the day. In her life she reconciled aspects of spirituality often seen to be either mutually exclusive or in conflict. This married lay woman was both a mystic and a humanitarian, a constant contemplative, yet daily immersed in the physical care of the sick and the destitute. For the last five centuries she has been the inspiration of such spiritual greats as Francis de Sales, Robert Bellarmine, Fenelon. Newman and Hecker. -

The Spiritual Canticle of St. John of the Cross—A Translation by Fr

The Spiritual Canticle of St. John of the Cross—a Translation by Fr. Bonaventure Sauer, OCD Discalced Carmelite Province of St. Therese (Oklahoma) A few years ago I worked up my own translation of The Spiritual Canticle by St. John of the Cross. I enjoyed the exercise and found it a good way to study the poem more closely. In addition to the translation itself, you will find in what follows below, first, a very brief introduction stressing the importance of reading the poem as a narrative, for that is what gives the poem its coherence, its structure as a story. Otherwise, it can seem like little more than a parade of images, with no rhyme or reason of its own, to which allegorical meanings must then be applied. Second, I have attached to my translation of the poem some marginal notes, set out in a column to the right, parallel to the text of the translation. These notes are intended to illuminate this simple narrative structure of the poem. Lastly, after the translation, I have appended a few reflections on the approach or method I used in translating the poem. 1. The Poem The Spiritual Canticle—read as a Story The Spiritual Canticle of St. John of the Cross is not an easy poem. That is true for many reasons. Reading it for the first time, it can seem like a string of images filing by like so many floats in a parade. But how do the images hold together? And how do the individual lines and stanzas form a whole? In order to find that overarching unity most people probably look to the commentary. -

St. Francis of Assisi Library Author Title Section Call#1 Category: SPIRITUALITY

St. Francis of Assisi Library Author Title Section Call#1 Category: SPIRITUALITY Allen, Paul Francis of Assisi's Canticle of the Creatures ALLE 12 Arminjon, Charles End of the Present World ARMI 16 Bacovcin, Helen Way of a Pilgrim and the Pilgrim Continues His Way BACO 09 Baker, Denise Showings of Julian of Norwich BAKE 09 Barry , Patrick Saint Benedict's Rule BARR 07 Barry, William A. Finding God in All Things BARR 08 Bodo, Murray Enter Assisi BODO 15 Bonhoeffer, Dietrich Cost of Discipleship, The BONH 08 Brady, Ignatius C., Translator Writings of Saint Francis of Assisi BRAD 10 Cantalamessa, Raniero Sober Intoxication of the Spirit CANT 07 Carrigan, Henry LIttle Talks with God CARR 16 Casey, Michael Guide to Living in the Truth, A CASE 09 Casey, Michael Strangers to the City CASE 07 Caussade, Jean-Pierre Joy of Full Surrender, The CAUS 16 Caussade, Jean-Pierre Abandonment to Divine Providence CAUS 12 Chittister, Joan Rule of Benedict, The CHIT 12 Chrysostom, John Love Chapter, The CHRY 16 Collier, Winn Let God COLL 15 Colledge, Edmund (Translator) Julian of Norwich Showings COLL 08 Corrigan, Felicitas, O.S.B. Saints Humanly Speaking, The CORR 07 Cousins, Ewert Bonaventure COUS 07 Deming, Lynne Feminine Mystic, The DEMI 14 De Montfort, St. Louis Mary God Alone DEMO 07 De Sales, St Francis Introduction to the Devout Life DESA 11 De Sales, St Francis Thy Will Be Done DESA 98 de Waal, Esther Seeking God DEWA 04 Durka, Gloria Praying with Hildegard of Bingen DURK 10 Evans, G. R., Translator & Bernard of Clairvaux EVAN 10 Fagin,Foreword Gerald Putting on the Heart of Christ FAGI 12 Fenelon, Francois Talking With God FENE 16 Hindsley, Leonard P. -

St. John of the Cross: Session 7 with James Finley Jim Finley: Greetings

St. John of the Cross: Session 7 with James Finley Jim Finley: Greetings. I’m Jim Finley. Welcome to Turning to the Mystics. Jim Finley: Greetings, everyone, and welcome into our time together turning for guidance to the teachings of the Christian mystic, St. John of the Cross. In the previous session, I, in a sense, summarized The Dark Night, this transformative way of life which St. John of the Cross says we come to perfect union with God in so far as possible on this earth through love. And in this session, I want to move on from The Dark Night to the mystical union with God that blossoms in this night as it comes to fruition. So backing up a bit to put this into a context, remember in the opening session on John of the Cross when we were just starting out, we spoke of his life at that point where he was ordained to the priesthood in the Carmelite Order. And he was approached by Theresa of Avila, soon to be St. Mary’s of Avila, who was a cloistered nun with the sisters in the Carmelite Order, same order that he was in. Jim Finley: It says she felt called to reform the Carmelite Order and return to the primitive observance of a return to simplicity, prayer, and poverty and asked would he be willing to join her in reforming the houses of the men in a primitive observance. He prayed over it in a discerned call to do that. He informed the priest of his intentions to do this. -

A Comparative Study of Amir Khusrau and Jacopone Da Todi

“MYSTICISM, LOVE AND POETRY” A Comparative study of Amir Khusrau and Jacopone da Todi Dissertation submitted to Jawaharlal Nehru University for award of the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Marta Irene Franceschini Centre for Historical Studies School of Social Science JAWAHARLAL NEHRU UNIVERSITY New Delhi – 110067 2012 I am the only enemy that stands between me and salvation. Jacopone da Todi Poetry became my plague. Too bad Khusrau never observed silence, never quit talking. Amir Khusrau CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Chapter 1 POETRY, MYSTICISM AND SAINTHOOD a) Poetry and Communication b) Poetry and Mysticism c) Poetry and Islam in the Thirteenth Century d) Poetry and Christianity in the Thirteenth Century e) Saints, Shaikhs and Sainthood Chapter 2 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND a) Medieval Italy: Socio-Economic Setting b) Jacopone da Todi c) Medieval India: Socio-Economic Setting b) Amir Khusaru Chapter 3 LYRICAL FEATURES: DIFFERENCES AND ANALOGIES. a) The Works b) The Style c) The Language d) The Music Chapter 4 POEMS TO POEMS: THE METAPHYSIC OF LOVE a) The spiritual masters b) Poems to poems CONCLUSION INTRODUCTION Amir Khusrau and Jacopone da Todi lived in the same century but in very distant places. The former in the splendour of Delhi, the capital of the Delhi Sultanate, the latter in a small town of central Italy, under the sovereignty of the Catholic Church. However, both were men of mystical orientations whose work gave birth to an everlasting genre of sacred music: qawwali for Khusrau and Stabat Mater for Jacopone. Not only are both these musical genres still played and sung today using the two poets’ original verses but, over the ensuing seven centuries, have also managed to maintain their prestige and popularity. -

Flos Carmeli Provincial Council Sets Visita

Oklahoma Province Spring 2013 Secular Order of Vol. XXIII, No.2 Discalced Carmelites Flos Carmeli Provincial Council sets visita- tions, attendance policy . Praised be Jesus Christ. Dear Sisters and Brothers in Carmel, Inside this This year started out as a very busy one for the Provincial Council. Having completed 14 visitations and made more issue than 20 discernments for our study groups, we set out at our Annual Meeting reviewing our progress so far and to look Resolving conflicts ahead for what we hope to accomplish in 2013. 6 The Annual PC Meeting was held at the beginning of February The spirituality of at Mount Carmel Center in Dallas. By planning to hold it at the OCDS legisla- that time we were able to meet Fr. John Grennan OCD from Ireland, who resides in Rome and is a General Definitor. He tion 16 was in our Province making visitations to the friars and nuns at various monasteries. Fr. Luis Castranada OCD, our Pro- Meet Pere Jacques vincial, also visited with us over the luncheon table. Both fri- 18 ars wish to assure you of their prayers and support. A dramatization of We had a wonderful opportunity to spend part of an afternoon the Third Dwelling with Fr. Grennan and exchange ideas. He was very interested in how our visitations were conducted and amazed at the ad- Place 20 vancements that the OCDS has accomplished. He left us News from around (Continued on page 2) the province 23 (Continued from page 1) with the message to live St. Paul’s message to the Romans, in Romans 12: 2, “Do not model your- selves on the behavior of the world around you, but let your behavior change, modeled by your new mind….” He urged us all to let our minds be renewed, to be radiant, happy and joyful in the Lord, and to detach from anything negative, which can be an insidious form of attachment itself, and to live in the place of great happiness. -

Stabat Mater Dolorosa by Jacopone Da Todi (1230-1306) a Reflection

Stabat mater dolorosa by Jacopone da Todi (1230-1306) A Reflection by Canon Jim Foley The liturgical hymn known as Stabat Mater is another example of the great medieval tradition of religious poetry which has enriched the church for a thousand years. Unfortunately, it has suffered much the same fate as the Dies Irae and Vexilla Regis. It has quietly disappeared from the public liturgy of the Church since Vatican II. If it has survived longer than most, it is probably because of the Stations of the Cross, a devotion still popular during Lent and Passiontide. One verse of our hymn is sung between the reflections associated with each Station. The verses are usually sung to a simple, but attractive plainsong melody, as the congregation processes around the church, pausing before each Stataion. The devotion itself, like the Christmas Crib, is attributed to Saint Francis of Assisi (1181- 1226). It was certainly promoted by the Franciscan tradition of piety to the extent that, for many years, the Franciscans alone had the faculty to dedicate the Stations of the Cross in places of worship. The Franciscans also pioneered research and excavations in the Holy Land in the hope of discovering the original Via Dolorosa across Jerusalem to Calvary. However, research by rival Jesuit and Dominican scholars in the Holy City has led to the promotion of other possible routes for the Via Dolorosa! While a student in Jerusalem I was surprised to see a citizen carrying a heavy wooden cross on his shoulders as he made his way, evidently unnoticed, along a busy street. -

Saint John of the Cross Was Born at from Its Thoughtful Remembrance of Past Fontiveros in Spain in 1540

Saint John of5 9 the1 Cross 1 5 4 2 - 1 P ARADISE n his Spiritual Canticle, Saint John of Still in the Ascent to Mt. Carmel the the Cross describes in great detail the Saint explains: “By their participation, effects of the soul’s union with God: “It souls possess the same gifts that God Iis simply impossible to describe what Himself naturally possesses. Their power God shares with the soul in this intimate is precisely the power of God, equal to union. Nothing can actually be expressed Him and His followers. Thus, St. Peter since it is impossible to say anything says: ‘Grace and peace be yours in fullest that would come close to what God is measure through the knowledge of God in Himself, since it is God who so gives and Jesus our Lord. His divine power Himself to a soul that is so transformed has granted to us all things that pertain from itself to Him. They become then as to life and godliness, through the knowl- two persons in one even though they edge of Him who called us to His own remain essentially and uniquely as in life, glory and excellence, by which He has as the rays of the sun through a window granted to us His precious and very great glass, as coal and fire, as the light from promises, that through these you may the stars and from the sun. Thus, so as to escape from the corruption that is in the understand how much the soul receives world because of passion and become from God in this unity, the soul can do partakers of the divine nature.’ (2 Pt 1, 2- no less, in my opinion, than to simply 4). -

13. "How Gently and Lovingly You Awake in My Heart" As We Begin

13. "How Gently and Lovingly You Awake in My Heart" As we begin this topic, let us reflect on these words: "It should be known that if anyone is seeking God, the Beloved is seeking that person much more" (FB 3.28). In this topic, we will explore "The Living Flame of Love," in which John further examines spiritual marriage. As we will see, John of the Cross shares with his directees the most profound encounter that he had with Jesus Christ of which we know today. I. Prologue: In the prologue to his final poem and commentary, "The Living Flame of Love," John of the Cross, as with the climax of "The Spiritual Canticle," brings his readers to the very vestibule of heaven. In the prologue to the "Flame", John anticipates a question: Why, when already he had written about spiritual marriage, is he doing so once more in the "Flame"? John responds that he treats in this poem and commentary "the highest degree of perfection one can reach in this life (transformation in God), [because] these stanzas treat of a love deeper in quality and more perfect within this very state of transformation" (FB Prologue). John wants us to know that there are degrees in spiritual marriage as one descends deeper and deeper into the gracious Mystery who is God. In the heading to the prologue of the "Flame" we learn that the commentary was requested by his friend and benefactor Dona Ana del Mercado y Penalosa who, in the prologue, he calls "a very noble and devout lady." Once again, John wants to address the ineffability of the encounter with God: "Since they [the stanzas] deal with matters so interior and spiritual, for which words are usually lacking—in that the spiritual surpasses the sense - I find it difficult to say something of their content; also, one speaks badly of the intimate depths of the spirit if one does not do so with a deeply recollected soul" (FB, Prologue).