Stabat Mater Dolorosa by Jacopone Da Todi (1230-1306) a Reflection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antonio Vivaldi1678-1741

Antonio Vivaldi 1678-1741 Pietà Sacred works for alto Clarae stellae, scintillate rv 625 Stabat Mater rv 621 Filiae maestae Jerusalem rv 638 from Gloria rv 589: Domine Deus Longe mala, umbrae, terrores rv 629 Salve Regina rv 618 Concerto for strings and continuo rv 120 Philippe Jaroussky countertenor Ensemble Artaserse 2 Pietà Vivaldi is the composer who has brought me the most luck throughout my career – by a long way. After numerous recordings devoted to less well known figures such as Johann Christian Bach, Caldara and Porpora, I felt a need that was as much physical as musical to return to this great composer. This release focuses on his motets for contralto voice, thereby rounding off – after discs of his cantatas and opera arias – a three-part set of recordings of music by the Red Priest. His celebrated Stabat Mater is one of the great classics of the countertenor reper toire, but I also very much wanted to record the motet Longe mala, umbrae, terrores, a piece that I find absolutely fascinating. This disc is a milestone for me, because it is the first time I have made a recording with my own ensemble Artaserse in a fuller, more orchestral line-up. It was an exciting experience, both on the musical and on the personal level, to direct so many musicians and sing at the same time. I would like to thank all the musicians who took part for their talent, patience and dedication, and I hope that this recording will mark the beginning of a new direction in my musical career. -

Ecce Mater Tua

Ecce Mater Tua A Journal of Mariology Vol. 4 June 12, 2021 Feast of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Editorial Board Editor Dr. Mark Miravalle, S.T.D. Franciscan University of Steubenville, Ohio Associate Editor Robert Fastiggi, S.T.D. Sacred Heart Major Seminary, Michigan Managing Editor Joshua Mazrin Catholic Diocese of Venice, Florida Advisory Board Msgr. Arthur Calkins, S.T.D. Vatican Fr. Daniel Maria Klimek Ecclesia Dei, Emeritus T.O.R. Franciscan University of Steubenville, Ohio Fr. Giles Dimock, O.P., S.T.D. Pontifical University of St. Dr. Stephen Miletic Thomas Aquinas (Angelicum), Emeritus Franciscan University of Steubenville, Ohio Dr. Matthew Dugandzic, Ph.D. St. Mary’s Seminary and Christopher Malloy, Ph.D. University, Maryland University of Dallas, Texas Dr. Luis Bejar Fuentes John-Mark Miravalle, S.T.D. Independent Editor and Journalist Mount St. Mary’s Seminary, Maryland Mr. Daniel Garland, Jr., Ph.D. Petroc Willey, Ph.D. (cand.) Ave Maria University, Florida Franciscan University of Steubenville, Ohio Scott Hahn, Ph.D. Franciscan University of Steubenville, Ohio Episcopal Advisors Telesphore Cardinal Toppo Archdiocese Bishop Jaime Fuentes of Ranchi, India Bishop of Minas, Uruguay Cardinal Sandoval-Iñiguez Archdiocese of Guadalajara, Mexico i Ecce Mater Tua Ecce Mater Tua: A Journal of Mariology ISSN: 2573-5799 Instructions for Authors: To submit a paper for consideration, please first make sure that all personal references are stripped from the text and file properties, then email the document in Microsoft Word format (.doc or .docx) or in rich text format (.rtf) to [email protected]. To ensure a smooth editorial process, please include a 250–350-word abstract at the beginning of the article and be sure that formatting follows Chicago style. -

Marian Stations of the Cross

MARIAN STATIONS OF THE CROSS ST. LOUISE PARISH GATHERING SONG At The Cross Her Station Keeping (Stabat Mater Dolorosa) 1. At the cross her station keeping, 3. Let me share with thee his pain, Stood the mournful Mother weeping, Who for all my sins was slain, Close to Jesus to the last. Who for me in torment died. 2.Through her heart, his sorrow sharing, 4. Stabat Mater dolorósa All his bitter anguish bearing, Juxta crucem lacrimósa Now at length the sword has passed. Dumpendébat Fílius. Text: 88 7; Stabat Mater dolorosa; Jacapone da Todi, 1230-1306; tr. By Edward Caswall, 1814-1878, alt. OneLicense #U9879, LicenSingOnline FIRST STATION SECOND STATION L: Jesus is condemned to death L: Jesus carries his Cross All: The more I belong to God the more I will be condemned. (Matthew 5:10) All: I must carry the pain that is uniquely mine if I want to be a follower of Jesus. L: We adore You, O Christ, and we praise You. (Matthew 27:28-31) (GENUFLECT) L: We adore You… (GENUFLECT) All: Because by your holy Cross You have redeemed the world. All: Because by your holy Cross... L This can’t be happening…. L: I look at my Son… All: Hail Mary, full of grace. The Lord is with you. Blessed are you among women and blessed All: Hail Mary… is the fruit of your womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and Sing: Remember your love and your faithfulness, at the hour of our death. Amen O Lord. -

2018 Bibliography

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Bibliographies Research and Resources 2018 2018 Bibliography Sebastien B. Abalodo University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_bibliographies eCommons Citation Abalodo, Sebastien B., "2018 Bibliography" (2018). Marian Bibliographies. 17. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_bibliographies/17 This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Research and Resources at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Bibliographies by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Marian Bibliography 2018 Page 1 International Marian Research Institute University of Dayton, Ohio, USA Bibliography 2018 English Anthropology Calloway, Donald H., ed. “The Virgin Mary and Theological Anthropology.” Special issue, Mater Misericordiae: An Annual Journal of Mariology 3. Stockbridge, MA: Marian Fathers of the Immaculate Conception of the B.V.M., 2018. Apparitions Caranci, Paul F. I am the Immaculate Conception: The Story of Bernadette of Lourdes. Pawtucket, RI: Stillwater River Publications, 2018. Clayton, Dorothy M. Fatima Kaleidoscope: A Play. Haymarket, AU-NSW: Little Red Apple Publishing, 2018. Klimek, Daniel Maria. Medjugorje and the Supernatural Science, Mysticism, and Extraordinary Religious Experience. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018. Maunder, Chris. Our Lady of the Nations: Apparitions of Mary in Twentieth-Century Catholic Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. Musso, Valeria Céspedes. Marian Apparitions in Cultural Contexts: Applying Jungian Concepts to Mass Visions of the Virgin Mary. Research in Analytical Psychology and Jungian Studies. London: Routledge, 2018. Also E-book Sønnesyn, Sigbjørn. Review of William of Malmesbury: The Miracles of the Blessed Virgin Mary. -

The Virgin and the Basilisk - a Study of Medieval Women and Their Social Roles in Iacopone Da Todi’S (1230/36-1306) Laude.1

THE VIRGIN AND THE BASILISK - A STUDY OF MEDIEVAL WOMEN AND THEIR SOCIAL ROLES IN IACOPONE DA TODI’S (1230/36-1306) LAUDE.1 Annamaria Laviola Lund University During his lifetime, the Franciscan Iacopone da Todi (1230/36-1306) wrote a number of poems now known under the collective name of Laude. Influenced by different literary styles, such as Sicilian-Tuscan and differentiating itself from the Franciscan literary production of its time, Iacopone’s Laude discuss both religious and secular matters.2 This article is a study of the collection and the information for the modern reader about urban Italian women and their social roles in the thirteenth century, focusing on the following research questions: What are women’s different social roles according to the Laude? How are these roles constructed and described? In what ways does a study of the Laude help the historian to understand the ambivalent relation(s) within and between women’s roles in medieval society? Historiography Italian scholars writing during the second half of the twentieth century studied the Laude in order to answer questions of theological and literary character. Alvaro Bizziccari’s article on the concept of mystical love in the Laude, Franco Mancini’s focus on the variety of themes discussed by Iacopone and Elena Landoni’s study of the different literary styles that can be found in the Laude are but a few examples of this tendency.3 Even though much of the (Italian) scholarly interest for Iacopone da Todi has focused on subjects related to theology and literature, in recent years both Italian and international scholars have started to analyse other aspects of the texts. -

SAINT ALPHONSUS LIGUORI CATHOLIC CHURCH STATIONS of the CROSS

SAINT ALPHONSUS LIGUORI CATHOLIC CHURCH STATIONS of the CROSS Why do we pray the Stations of the Cross? The Via Crucis (Way of the Cross) is a devotion, particularly appropriate during Lent, by which we meditate upon the final earthly journey of Christ. Jerusalem is the city of the historical Way of the Cross. In the Middle Ages the attraction of the holy places of the Lord's Passion caused some pilgrims to reproduce them in their own city. There is also an historical devotion to the “dolorous journey of Christ” which consisted of journeying from one church to another in memory of Christ's Passion. This last stage of Christ's journey is unspeakably hard and painful, but He completed it out of love for the Father and for humanity. As we pray the Stations of the Cross, we are reminded of our own journey towards heaven. We may also meditate upon the demands of following Christ, which include carrying our own “crosses.” Adapted from Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy #131-133 What is a Plenary Indulgence? The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines an indulgence as “a remission before God of the temporal punishment due to sins whose guilt has already been forgiven...” Obtaining an indulgence requires prescribed conditions (i.e. being in a state of grace) and prescribed works (see below). "An indulgence is partial or plenary as it removes either part or all of the temporal punishment due to sin." We can gain indulgences for ourselves or for the dead. CCC #1471 “To acquire a plenary indulgence it is necessary to perform the work to which the indulgence is attached and to fulfill the following three conditions [within several days]: sacramental confession, Eucharistic Communion, and prayer for the intention of the Sovereign Pontiff. -

CONCLUSION in a Rather Famous Lauda by the Franciscan Poet

CONCLUSION In a rather famous lauda by the Franciscan poet Jacopo Benedetti (c. 1236–1306), better known as Jacopone (Big John) da Todi, he assails his brethren in Paris who he says “demolish Assisi stone by stone.” “That’s the way it is, not a shred left of the spirit of the Rule! […] With all their theol- ogy they’ve led the Order down a crooked path.”1 It is a complaint to which Jacopone returns many times in his writing.2 “Assisi” in this case seems to reflect the spiritual or, as David Burr says, a rigorist’s view of Franciscan virtue, which was basically centered on the ideals of evangelical poverty, charity, and penance. “Paris,” on the other hand, represents the arrogance of educated Friars—“an elite with special status and privileges” who looked down on their brothers.3 The conflict of the 1290s, when most of Jacopone’s laude were written, sing of struggles within the Order that go back to the 1220s, to a time when the friars were first grappling with their identity; and, as I have shown, this involved their chanting and preaching—the two aspects of the Franciscan mission of music that I have examined in this study. In Chapter One we saw that while the Regula non Bullata (Earlier Rule) of 1221 required all Franciscan friars to celebrate the Divine Offices, albeit in distinctive forms, the Regula Bullata (Later Rule) of 1223 privileged the clerical brothers as singers of the rite according to the Roman church.4 The Earlier Rule would not exclude the lay brothers from preaching, so long as they did not preach against the rites and practices of the Church and had the permission of the minister.5 But this was emended in the Later Rule, making preaching incumbent only on friars who had been properly examined, approved, and had “the office of preacher […] 1 “Tale qual è, tal è;/ non ci è relïone./ Mal vedemo Parisi,/ che àne destrutt’Asisi:/ co la lor lettoria messo l’ò en mala via.” [That’s the way it is—not a shred left of the spirit of the Rule! In sorrow and grief I see Paris demolish Assisi, stone by stone. -

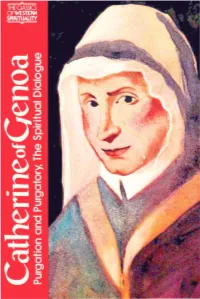

CATHERINE of GENOA-PURGATION and PURGATORY, the SPIRI TUAL DIALOGUE Translation and Notes by Serge Hughes Introduction by Benedict J

TI-ECLASSICS a:wESTEP.N SPIPlTUAIJTY i'lUBRi'lRY OF THEGREfiT SPIRITUi'lL Mi'lSTERS ··.. wbile otfui'ffKS h;·I�Jmas tJnd ;·oxiJ I:JOI'I!e be n plenli/111, books on \�stern mystics ucre-.trlfl o1re -bard /(I find'' ''Tbe Ptwlist Press hils just publisbed · an ambitious suies I hot sbu111d lnlp remedy this Jituation." Psychol�y li:x.Jay CATHERINE OF GENOA-PURGATION AND PURGATORY, THE SPIRI TUAL DIALOGUE translation and notes by Serge Hughes introduction by Benedict j. Grocschel. O.F.M. Cap. preface by Catherine de Hueck Doherty '.'-\1/tbat I /ltJt'e saki is notbinx Cllmf'dretltowbat lfeeluitbin• , t/Hu iJnesudwrresponden�.· :e /J/ hwe l�t•twec.'" Gtul and Jbe .\ou/; for u·ben Gfltlsees /be Srml pure llS it iJ in its orixins, lie Ill/(.� ,1( it ll'tlb ,, xlcmc.:c.•. drau·s it llrYIbitMIJ it to Himself u-ilh a fiery lfll•e u·hich by illt'lf cout.lunnibilult' tbe immorttJI SmJ/." Catherine of Genoa (}4-17-15101 Catherine, who lived for 60 years and died early in the 16th century. leads the modern reader directly to the more significant issues of the day. In her life she reconciled aspects of spirituality often seen to be either mutually exclusive or in conflict. This married lay woman was both a mystic and a humanitarian, a constant contemplative, yet daily immersed in the physical care of the sick and the destitute. For the last five centuries she has been the inspiration of such spiritual greats as Francis de Sales, Robert Bellarmine, Fenelon. Newman and Hecker. -

2013 Bibliography Gloria Falcão Dodd University of Dayton, [email protected]

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Bibliographies Research and Resources 2013 2013 Bibliography Gloria Falcão Dodd University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_bibliographies eCommons Citation Dodd, Gloria Falcão, "2013 Bibliography" (2013). Marian Bibliographies. Paper 3. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_bibliographies/3 This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Research and Resources at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Bibliographies by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bibliography 2013 Arabic Devotion Lūriyūl.; Yūsuf Jirjis Abū Sulaymān Mutaynī. al-Kawkab al-shāriq fī Maryam Sulṭānat al-Mashāriq : yashtamilu ʻalá sīrat Maryam al-ʻAdhrāʼ wa-manāqibihā wa-ʻibādatihā wa-yaḥtawī namūdhajāt taqwiyah min tārīkh al-Sharq wa-yunāsibu istiʻmāl hādhā al-kitāb fī al-shahr al-Maryamī. Bayrūt: al-Maṭbaʻah al-Kāthūlīkīyah, 1902. Ebook. Music Jenkins, Karl. UWG Concert Choir and Carroll Symphony Orchestra performing Stabat Mater by Karl Jenkins. Carrollton, Georgia: University of West Georgia, 2012. Cd. Aramaic Music Jenkins, Karl. UWG Concert Choir and Carroll Symphony Orchestra performing Stabat Mater by Karl Jenkins. Carrollton, Georgia: University of West Georgia, 2012. Cd. Catalan Music Llibre Vermell: The Red Book of Montserrat. Classical music library. With Winsome Evans and Renaissance Players. [S.l.]: Celestial Harmonies, 2011. eMusic. Chinese Theology Tian, Chunbo. Sheng mu xue. Tian zhu jiao si xiang yan jiu., Shen xue xi lie. Xianggang: Yuan dao chu ban you xian gong si, 2013. English Apparitions Belli, Mériam N. Incurable Past: Nasser's Egypt Then and Now. -

BATES, JAMES M., DMA Music in Honor of the Virgin Mary

BATES, JAMES M., D.M.A. Music in Honor of the Virgin Mary during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. (2010) Directed by Dr. Welborn Young. 50 pp. Veneration of the Virgin Mary was one of the most important aspects of Christianity during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and sacred music of the time incorporated many Marian concepts. The Virgin Mary was considered the greatest intercessor with God and Christ at a time when fear of Purgatory was strong. Prayers and devotions seeking her aid were among the most significant aspects of spiritual life, and texts of this kind were set to music for devotional use. Beyond her identity as intercessor, there were many additional conceptions of her, and these also found musical expression. The purpose of this study was, first, to explore the basic elements of Marian devotion, and, second, to examine how veneration of Mary was expressed musically. Seven musical compositions from c. 1200-1600 are examined as representative examples. The ―Marian aspects‖ of some compositions may be as straightforward as the use of texts that address Mary, or they may be found in musical and textual symbolism. Of special interest is a particular genre of motet used in private devotions. Precise and detailed information about how sacred music was used in the Middle Ages and Renaissance is scarce, but evidence related to this particular kind of devotional motet helps bring together a number of elements related to Marian meditative practices and the kind of physical settings in which these took place, allowing a greater understanding of the overall performance context of such music. -

7 Pope Francis Affirms the Essence of Marian Co-Redemption and Mediation

Ecce Mater Tua Pope Francis Affirms the Essence of Marian Co-redemption and Mediation ROBERT FASTIGGI Some people believe Pope Francis has rejected the teaching of Marian co- redemption because he has made several statements that suggest he prefers not to call Mary, the co-redemptrix. We need, though, to ask what the title means. The great Mariologist, Fr. Gabriele Maria Roschini, O.S.M. (1900– 1977), gave a very brief but accurate explanation of what it means to call Mary, the Co-redemptrix of the human race: The title Co-redemptrix of the human race means that the Most Holy Virgin cooperated with Christ in our reparation as Eve cooperated with Adam in our ruin.1 From prior statements of Pope Francis, it’s clear that he affirms this doctrine. In his morning meditation for the Solemnity of the Annunciation in 2016, the Holy Father states: “Today is the celebration of the ‘yes’… Indeed, in Mary’s ‘yes’ there is the ‘yes’ of all of salvation history and there begins the ultimate ‘yes’ of man and of God: there God re-creates, as at the beginning, with a ‘yes’, God made the earth and man, that beautiful creation: with this ‘yes’ I come to do your will and more wonderfully he re-creates the world, he re-creates us all”. Pope Francis recognizes Mary’s “yes” as an expression of her active role in salvation history—a role that we can call coredemptive. During his January 26, 2019 vigil with young people in Panama, the Holy Father spoke of Mary as “the most influential woman in history.” He also referred to the Blessed Virgin as the “influencer of God.” Mary influenced God by saying yes to his invitation and by trusting in his promises. -

The Way Cross

Because of Covid-19 concerns, please keep this booklet as your personal copy to use throughout Lent. The Way of the Cross St. Benedict Catholic Church A Commentary on THE STATIONS OF THE CROSS– Could you walk a mile in Jesus’s shoes? The Stations of the Cross bring us closer to Christ as we meditate on the great love He showed for us in His most sorrow- ful Passion! Tradition traces this loving tribute to our Lord back to the Blessed Mother retracing her son’s last steps along what became known as the Via Do- lorosa (the Sorrowful Way) on His way to His Crucifixion at Calvary in Jerusalem. Pilgrims to the Holy Land commemorated Christ’s Passion in a similar manner as early as the 4th century A.D. The Stations of the Cross developed as devotion in earnest, however, around the 13th to 14th centuries. It became a way of allow- ing those who could not make the long, expensive, arduous journey to Jerusa- lem to make a pilgrimage in prayer, at least, in their church! Although the origi- nal number of stations varied greatly, they became fixed at 14 in the 18th centu- ry. The Stations of the Cross themselves are usually represented in churches by a series of 14 pictures or sculptures covering our Lord's Passion. They are meant to be “stopping points” along the journey for prayer and meditation. The Stations of the Cross provide us with great material for prayer and medita- tion. Tracing Jesus’s journey from condemnation to crucifixion increases both our sorrow for our sins and our desire for His help in avoiding temptations and in bearing our own crosses.