An Interesting Phenomenon in the History of Music Is That Many Pieces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marian Stations of the Cross

MARIAN STATIONS OF THE CROSS ST. LOUISE PARISH GATHERING SONG At The Cross Her Station Keeping (Stabat Mater Dolorosa) 1. At the cross her station keeping, 3. Let me share with thee his pain, Stood the mournful Mother weeping, Who for all my sins was slain, Close to Jesus to the last. Who for me in torment died. 2.Through her heart, his sorrow sharing, 4. Stabat Mater dolorósa All his bitter anguish bearing, Juxta crucem lacrimósa Now at length the sword has passed. Dumpendébat Fílius. Text: 88 7; Stabat Mater dolorosa; Jacapone da Todi, 1230-1306; tr. By Edward Caswall, 1814-1878, alt. OneLicense #U9879, LicenSingOnline FIRST STATION SECOND STATION L: Jesus is condemned to death L: Jesus carries his Cross All: The more I belong to God the more I will be condemned. (Matthew 5:10) All: I must carry the pain that is uniquely mine if I want to be a follower of Jesus. L: We adore You, O Christ, and we praise You. (Matthew 27:28-31) (GENUFLECT) L: We adore You… (GENUFLECT) All: Because by your holy Cross You have redeemed the world. All: Because by your holy Cross... L This can’t be happening…. L: I look at my Son… All: Hail Mary, full of grace. The Lord is with you. Blessed are you among women and blessed All: Hail Mary… is the fruit of your womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and Sing: Remember your love and your faithfulness, at the hour of our death. Amen O Lord. -

Gabriel Jackson

Gabriel Jackson Sacred choral WorkS choir of St Mary’s cathedral, edinburgh Matthew owens Gabriel Jackson choir of St Mary’s cathedral, edinburgh Sacred choral WorkS Matthew owens Edinburgh Mass 5 O Sacrum Convivium [6:35] 1 Kyrie [2:55] 6 Creator of the Stars of Night [4:16] Katy Thomson treble 2 Gloria [4:56] Katy Thomson treble 7 Ane Sang of the Birth of Christ [4:13] Katy Thomson treble 3 Sanctus & Benedictus [2:20] Lewis Main & Katy Thomson trebles (Sanctus) 8 A Prayer of King Henry VI [2:54] Robert Colquhoun & Andrew Stones altos (Sanctus) 9 Preces [1:11] Simon Rendell alto (Benedictus) The Revd Canon Peter Allen precentor 4 Agnus Dei [4:24] 10 Psalm 112: Laudate Pueri [9:49] 11 Magnificat (Truro Service) [4:16] Oliver Boyd treble 12 Nunc Dimittis (Truro Service) [2:16] Ben Carter bass 13 Responses [5:32] The Revd Canon Peter Allen precentor 14 Salve Regina [5:41] Katy Thomson treble 15 Dismissal [0:28] The Revd Canon Peter Allen precentor 16 St Asaph Toccata [8:34] Total playing time [70:22] Recorded in the presence Producer: Paul Baxter All first recordings Michael Bonaventure organ (tracks 10 & 16) of the composer on 23-24 Engineers: David Strudwick, (except O Sacrum Convivium) February and 1-2 March 2004 Andrew Malkin Susan Hamilton soprano (track 10) (choir), 21 December 2004 (St Assistant Engineers: Edward Cover image: Peter Newman, The Choir of St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Asaph Toccata) and 4 January Bremner, Benjamin Mills Vapour Trails (oil on canvas) 2005 (Laudate Pueri) in St 24-Bit digital editing: Session Photography: -

2013 Bibliography Gloria Falcão Dodd University of Dayton, [email protected]

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Bibliographies Research and Resources 2013 2013 Bibliography Gloria Falcão Dodd University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_bibliographies eCommons Citation Dodd, Gloria Falcão, "2013 Bibliography" (2013). Marian Bibliographies. Paper 3. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_bibliographies/3 This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Research and Resources at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Bibliographies by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bibliography 2013 Arabic Devotion Lūriyūl.; Yūsuf Jirjis Abū Sulaymān Mutaynī. al-Kawkab al-shāriq fī Maryam Sulṭānat al-Mashāriq : yashtamilu ʻalá sīrat Maryam al-ʻAdhrāʼ wa-manāqibihā wa-ʻibādatihā wa-yaḥtawī namūdhajāt taqwiyah min tārīkh al-Sharq wa-yunāsibu istiʻmāl hādhā al-kitāb fī al-shahr al-Maryamī. Bayrūt: al-Maṭbaʻah al-Kāthūlīkīyah, 1902. Ebook. Music Jenkins, Karl. UWG Concert Choir and Carroll Symphony Orchestra performing Stabat Mater by Karl Jenkins. Carrollton, Georgia: University of West Georgia, 2012. Cd. Aramaic Music Jenkins, Karl. UWG Concert Choir and Carroll Symphony Orchestra performing Stabat Mater by Karl Jenkins. Carrollton, Georgia: University of West Georgia, 2012. Cd. Catalan Music Llibre Vermell: The Red Book of Montserrat. Classical music library. With Winsome Evans and Renaissance Players. [S.l.]: Celestial Harmonies, 2011. eMusic. Chinese Theology Tian, Chunbo. Sheng mu xue. Tian zhu jiao si xiang yan jiu., Shen xue xi lie. Xianggang: Yuan dao chu ban you xian gong si, 2013. English Apparitions Belli, Mériam N. Incurable Past: Nasser's Egypt Then and Now. -

BATES, JAMES M., DMA Music in Honor of the Virgin Mary

BATES, JAMES M., D.M.A. Music in Honor of the Virgin Mary during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. (2010) Directed by Dr. Welborn Young. 50 pp. Veneration of the Virgin Mary was one of the most important aspects of Christianity during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and sacred music of the time incorporated many Marian concepts. The Virgin Mary was considered the greatest intercessor with God and Christ at a time when fear of Purgatory was strong. Prayers and devotions seeking her aid were among the most significant aspects of spiritual life, and texts of this kind were set to music for devotional use. Beyond her identity as intercessor, there were many additional conceptions of her, and these also found musical expression. The purpose of this study was, first, to explore the basic elements of Marian devotion, and, second, to examine how veneration of Mary was expressed musically. Seven musical compositions from c. 1200-1600 are examined as representative examples. The ―Marian aspects‖ of some compositions may be as straightforward as the use of texts that address Mary, or they may be found in musical and textual symbolism. Of special interest is a particular genre of motet used in private devotions. Precise and detailed information about how sacred music was used in the Middle Ages and Renaissance is scarce, but evidence related to this particular kind of devotional motet helps bring together a number of elements related to Marian meditative practices and the kind of physical settings in which these took place, allowing a greater understanding of the overall performance context of such music. -

Musica Britannica

T69 (2021) MUSICA BRITANNICA A NATIONAL COLLECTION OF MUSIC Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens c.1750 Stainer & Bell Ltd, Victoria House, 23 Gruneisen Road, London N3 ILS England Telephone : +44 (0) 20 8343 3303 email: [email protected] www.stainer.co.uk MUSICA BRITANNICA A NATIONAL COLLECTION OF MUSIC Musica Britannica, founded in 1951 as a national record of the British contribution to music, is today recognised as one of the world’s outstanding library collections, with an unrivalled range and authority making it an indispensable resource both for performers and scholars. This catalogue provides a full listing of volumes with a brief description of contents. Full lists of contents can be obtained by quoting the CON or ASK sheet number given. Where performing material is shown as available for rental full details are given in our Rental Catalogue (T66) which may be obtained by contacting our Hire Library Manager. This catalogue is also available online at www.stainer.co.uk. Many of the Chamber Music volumes have performing parts available separately and you will find these listed in the section at the end of this catalogue. This section also lists other offprints and popular performing editions available for sale. If you do not see what you require listed in this section we can also offer authorised photocopies of any individual items published in the series through our ‘Made- to-Order’ service. Our Archive Department will be pleased to help with enquiries and requests. In addition, choirs now have the opportunity to purchase individual choral titles from selected volumes of the series as Adobe Acrobat PDF files via the Stainer & Bell website. -

7 Pope Francis Affirms the Essence of Marian Co-Redemption and Mediation

Ecce Mater Tua Pope Francis Affirms the Essence of Marian Co-redemption and Mediation ROBERT FASTIGGI Some people believe Pope Francis has rejected the teaching of Marian co- redemption because he has made several statements that suggest he prefers not to call Mary, the co-redemptrix. We need, though, to ask what the title means. The great Mariologist, Fr. Gabriele Maria Roschini, O.S.M. (1900– 1977), gave a very brief but accurate explanation of what it means to call Mary, the Co-redemptrix of the human race: The title Co-redemptrix of the human race means that the Most Holy Virgin cooperated with Christ in our reparation as Eve cooperated with Adam in our ruin.1 From prior statements of Pope Francis, it’s clear that he affirms this doctrine. In his morning meditation for the Solemnity of the Annunciation in 2016, the Holy Father states: “Today is the celebration of the ‘yes’… Indeed, in Mary’s ‘yes’ there is the ‘yes’ of all of salvation history and there begins the ultimate ‘yes’ of man and of God: there God re-creates, as at the beginning, with a ‘yes’, God made the earth and man, that beautiful creation: with this ‘yes’ I come to do your will and more wonderfully he re-creates the world, he re-creates us all”. Pope Francis recognizes Mary’s “yes” as an expression of her active role in salvation history—a role that we can call coredemptive. During his January 26, 2019 vigil with young people in Panama, the Holy Father spoke of Mary as “the most influential woman in history.” He also referred to the Blessed Virgin as the “influencer of God.” Mary influenced God by saying yes to his invitation and by trusting in his promises. -

The Way Cross

Because of Covid-19 concerns, please keep this booklet as your personal copy to use throughout Lent. The Way of the Cross St. Benedict Catholic Church A Commentary on THE STATIONS OF THE CROSS– Could you walk a mile in Jesus’s shoes? The Stations of the Cross bring us closer to Christ as we meditate on the great love He showed for us in His most sorrow- ful Passion! Tradition traces this loving tribute to our Lord back to the Blessed Mother retracing her son’s last steps along what became known as the Via Do- lorosa (the Sorrowful Way) on His way to His Crucifixion at Calvary in Jerusalem. Pilgrims to the Holy Land commemorated Christ’s Passion in a similar manner as early as the 4th century A.D. The Stations of the Cross developed as devotion in earnest, however, around the 13th to 14th centuries. It became a way of allow- ing those who could not make the long, expensive, arduous journey to Jerusa- lem to make a pilgrimage in prayer, at least, in their church! Although the origi- nal number of stations varied greatly, they became fixed at 14 in the 18th centu- ry. The Stations of the Cross themselves are usually represented in churches by a series of 14 pictures or sculptures covering our Lord's Passion. They are meant to be “stopping points” along the journey for prayer and meditation. The Stations of the Cross provide us with great material for prayer and medita- tion. Tracing Jesus’s journey from condemnation to crucifixion increases both our sorrow for our sins and our desire for His help in avoiding temptations and in bearing our own crosses. -

572840 Bk Eton EU

Music from THE ETON CHOIRBOOK LAMBE • STRATFORD • DAVY BROWNE • KELLYK • WYLKYNSON TONUS PEREGRINUS Music from the Eton Choirbook Out of the 25 composers The original index lists more represented in the Eton than 60 antiphons – all votive The Eton Choirbook – a giant the Roses’, and the religious reforms and counter-reforms Choirbook, several had strong antiphons designed for daily manuscript from Eton College of Henry VIII and his children. That turbulence devastated links with Eton College itself: extraliturgical use and fulfilling Chapel – is one of the greatest many libraries (including the Chapel Royal library) and Walter Lambe and, quite Mary’s prophecy that “From surviving glories of pre- makes the surviving 126 of the original 224 leaves in Eton possibly, John Browne were henceforth all generations shall Reformation England. There is a College Manuscript 178 all the more precious, for it is just there in the late 1460s as boys. call me blessed”; one of the proverb contemporary with the one of a few representatives of several generations of John Browne, composer of the best known – and justifiably so Eton Choirbook which might English music in a period of rapid and impressive astounding six-part setting of – is Walter Lambe’s setting of have been directly inspired by development. Eton’s chapel library itself had survived a Stabat mater dolorosa 5 may have gone on to New Nesciens mater 1 in which the composer weaves some the spectacular sounds locked forced removal in 1465 to Edward IV’s St George’s College, Oxford, while Richard Davy was at Magdalen of the loveliest polyphony around the plainchant tenor up in its colourful pages: “Galli cantant, Italiae capriant, Chapel – a stone’s throw away in Windsor – during a College, Oxford in the 1490s. -

Stabat Mater

in five movements for quintet for in five movements stabat mater in five movements for quintet Gianmario Liuni 1 if faith gives your life meaning and music is your Sequentia vocation, sooner or later your heart will encoura- (in Festo Septem ge you to express both of these indispensable ele- Dolorum B.M.V.) ments of your daily life through your music. Just as it comes naturally to each musician to Text: dedicate a piece to his wife or children because Attributed there is nothing more marvelous in life, which is to Jacopone da Todi something i've done as well, i spontaneously de- cided, albeit with trepidation and reverence, to ho- nor the virgin mary, our mother, with my music. but how does one honor the virgin mary? What does it truly mean to pay homage to her? my first sincere intent is to give her "something beautiful", just as one offers a lit candle or a flo- wer. but there is more. the mother of God is the Co-redemptrix who renews our faith through Christ and indicates the path to reach him. therefore, paying homage to the virgin mary through music means speaking of her so that she speaks to us about her son Jesus. it means writing music that uplifts us, revealing the unique mystery of the son and mother's holiness that allows us to comprehend in the gazes of the mother and son the "sanctity of suffering seen in the mirror and recognized as the same" (J.m. ibañes Langlois). this was not the first time thati had worked on a sacred piece. -

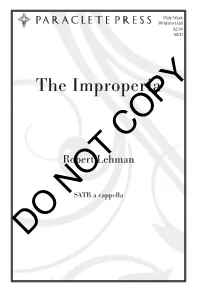

The Improperia I Did Raise Thee on High with Great Power

10 Holy Week paraclete press PPM01916M U $2.90 # # œ M/D & # ## œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ w where- in have I wear- ied thee? Test--- i fy a gainst me. œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ ˙ U ? # # œ œ œ œœ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œœ œ œ ˙ œ œ ww # ## œ Cantor #### & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ The Improperia I did raise thee on high with great power: #### & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ and thou hast hang-- ed me up on the gib- bet of the Cross. Full Choir p COPY # # œ # ## ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙˙ œœ œ œ œ ˙. œ œ œ . & ˙ ˙ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ O my peo- ple, what have I done un- to thee? or Robert Lehman œ ˙ ˙ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ ? # # ˙ ˙ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ # ## œ œ œ ˙. œ NOTSATB a cappella # # œ U & # ## œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ w where- in have I wear- ied thee? Test--- i fy a gainst me. œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ ˙ U ? # # œ œ œ œœ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œœ œ œ ˙ œ œ ww DO # ## œ PPM01916M 9 Cantor #### & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ I did smite the kings of the Can-- aan ites for thy sake: # ## & # # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ andœ thou hast smit- ten my head with a reed. -

Stabat Mater Dolorosa by Jacopone Da Todi (1230-1306) a Reflection

Stabat mater dolorosa by Jacopone da Todi (1230-1306) A Reflection by Canon Jim Foley The liturgical hymn known as Stabat Mater is another example of the great medieval tradition of religious poetry which has enriched the church for a thousand years. Unfortunately, it has suffered much the same fate as the Dies Irae and Vexilla Regis. It has quietly disappeared from the public liturgy of the Church since Vatican II. If it has survived longer than most, it is probably because of the Stations of the Cross, a devotion still popular during Lent and Passiontide. One verse of our hymn is sung between the reflections associated with each Station. The verses are usually sung to a simple, but attractive plainsong melody, as the congregation processes around the church, pausing before each Stataion. The devotion itself, like the Christmas Crib, is attributed to Saint Francis of Assisi (1181- 1226). It was certainly promoted by the Franciscan tradition of piety to the extent that, for many years, the Franciscans alone had the faculty to dedicate the Stations of the Cross in places of worship. The Franciscans also pioneered research and excavations in the Holy Land in the hope of discovering the original Via Dolorosa across Jerusalem to Calvary. However, research by rival Jesuit and Dominican scholars in the Holy City has led to the promotion of other possible routes for the Via Dolorosa! While a student in Jerusalem I was surprised to see a citizen carrying a heavy wooden cross on his shoulders as he made his way, evidently unnoticed, along a busy street. -

16Th Century

16th century notes towards the end of the piece are deliberate, and won’t seem so bad if you play them well? In bars 115 and 117 Cherici reproduces the notes as Mudarra had them, but I EDITIONS wonder if there is a case for changing them to match the rest of the sequence from bars 111 to 122, if only in a footnote. Anthology of Spanish Renaissance Music In three of the Fantasias by Mudarra the player is required for Guitar: to use the “dedillo” technique – using the index finger to Works by Milán, Narváez, Mudarra, Valderrábano, Pisador, play up and down like a plectrum. Of the nine pieces from Fuenllana, Daça, Ortiz Enriquez Valderrábano’s Silva de Sirenas (1547), three are Transcribed by Paolo Cherici marked “Primero grado”, i.e. easiest to play. Diego Pisador is Bologna: Ut Orpheus, 2017 CH273 less well known than the other vihuelists, perhaps because accid his Libro de musica de vihuela (1552) contains pages and his well-chosen anthology comprises solo music pages of intabulations of sacred music by Josquin and for the vihuela transcribed into staff notation others. However, there are some small-scale attractive for the modern guitar, and music for the viola da pieces of which Cherici picks five including a simple setting T of La Gamba called Pavana muy llana para tañer. The eight gamba with SATB grounds arranged for two guitars. For the vihuela pieces the guitar must have the third string tuned pieces from Miguel de Fuenllana’s Orphenica Lyra (1554) a semitone lower to bring it into line with vihuela tuning.