7255 Tibetan Monks from Bhutan Vol 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chhukha 10 6.1 Dzongkhag 10 6.2 Eleven (11) Gewogs Criteria, Weightage and Allocation for Gewogs 12 7

Twelfth Five Year Plan Document (Volume III) © Copyright Gross National Happiness Commission (2019) Published by: Gross National Happiness Commission, Royal Government of Bhutan. “Looking ahead, we have a new five-year plan, and a great number of responsibilities of national importance before us. We must work together in order to build an extraordinary, strong, secure, and peaceful future for Bhutan.” ISBN: 978-99936-55-04-6 His Majesty The Druk Gyalpo ISBN: 978-99936-55-05-3 111th National Day, Samtse, 17th December, 2018 TWELVE FIVE YEAR PLAN_BINU_12.indd 3 5/24/2019 10:52:20 AM “Looking ahead, we have a new five-year plan, and a great number of responsibilities of national importance before us. We must work together in order to build an extraordinary, strong, secure, and peaceful future for Bhutan.” His Majesty The Druk Gyalpo 111th National Day, Samtse, 17th December, 2018 TWELVE FIVE YEAR PLAN_BINU_12.indd 3 5/24/2019 10:52:20 AM Twelfth Five Year Plan (2018-2023), Punakha Dzongkhag PRIME MINISTER 2nd February, 2019 FOREWORD e 12th Five Year Plan (FYP) commences amid numerous auspicious occasions that hold special signi cance for all Bhutanese. Our Nation celebrated the 12th year of glorious reign of His Majesty e Druk Gyalpo and 111 years of the institution of Monarchy and nation building. e nation continues to enjoy the blessings of Yabjey-Damba, His Majesty e Fourth Druk Gyalpo. It witnessed the 22nd year of tireless service by His Holiness the 70th Je Khenpo for the wellbeing of the country and its people. e Nation’s Son, His Royal Highness e Gyalsey Jigme Namgyel Wangchuck continues to be a source of unbounded joy for all Bhutanese citizens. -

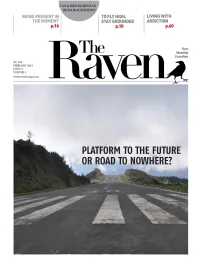

Bhutanese Karate Team Ranked Third

JANUARY/2013 01 COVER STORY 26 Learning to love 54 Say You Love Work Me 10 FIVE YEARS ON: A REVIEW OF THE RULING PARTY 30 The Ultimate 58 Living with the Experience! Consequences of Teenage 34 Fiction The Raven’s Tshering Dorji provides an Pregnancy analysis of the DPT government, and postu- Revenge, by Karma lates on how its performance in the last five Singye Dorji years might impact the upcoming elections 65 Thumbs Up and in 2013 38 Social Me: To Be or Down Not To Be ? 40 Article A Moment For Self Reflection INTERVIEW 48 Legends Reflections on the Eternal Dragon 60 TÊTE Á TÊTE 49 Questioning the Quality of With Tshewang Tashi, who worked with Revenue Education and Customs 52 Restaurant Review MOST DISCUSSED 66 Experience e-Reader Vs a Book E-reader Vs Book TheThe Raven Raven OCTOBER,January, 2013 2012 1 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Sir/Madam, As president of the Hungarian Bhutan Friend- The articles carried by your magazine have been impressive and ship Society, I would love to receive electronic therefore, I have immense respect for your team. I hope you all copies of The Raven. Is it possible? If so, can will carry on your good work and soon start going indepth with the we distribute it to our members? stories. So far, The Raven doesn’t seem to be tilted to any political party and I hope it stays that way. I really liked the interview with my friend Karma Phuntsho. Karma Pem, businesswoman, Thimphu. Zoltan Valcsicsak. Got hold of the Raven, the latest one I guess, The Raven has been providing different views to various issues. -

Raven 01 04.Pdf

FEBRUARY/2013 COVER STORY 01 24 Can & Should Bhutan be Food-Sufficient? 10 TO FLY HIGH, Stay 30 From Lisbon GROUNDED with Love The introduction of domestic flights has been 34 Fiction a messy affair. MITRA RAJ revisits the pot- A Phone Call holes and bumps in the road and proposes that what goes up does not always have to 40 The Art of Writing come down 42 Feature A Letter to the Teen- Trastrophic Elements INTERVIEW 47 What’s your quirk? Tattoo Artist Yeshey Nidup, known as Chakox 64 TÊTE Á TÊTE With Tenzin Lekphell, spokesperson of Druk 48 In This Frame Nyamrup Tshogpa Bhutan Takin Party: “We keep Takin’ what we can and party” 52 Know your food MOST DISCUSSED Buckwheat 54 Restaurant Review 70 Art Page The Chew Innocent Smiles 56 Movie Review Jarim Sarim Yeshey Tshogay E-reader Vs Book 60 Living with Addiction 63 Thumbs Up and Down The Raven February, 2013 1 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Sir/Madam, I’ve just got hold of your third issue. And I must say that the overall design looks good, and the articles provide different views to vari- Tshering Dorji’s article Five years on: a review of the ruling party ous issues. was very well done. It was unbiased and summed up the DPT gov- ernment’s term rather honestly. Well done. My best wishes to the team. Tashi Gyaltshen, Thimphu. Gyeltshen, Mongar. Most media houses are looking at other alternatives to sustain I have always liked the Photo essay section in themselves. And in the process, their content is being hampered. -

Samdrup Jongkhar Dzongkhag

Twelfth Five Year Plan Document (Volume III) © Copyright Gross National Happiness Commission (2019) Published by: Gross National Happiness Commission, Royal Government of Bhutan. “Looking ahead, we have a new five-year plan, and a great number of responsibilities of national importance before us. We must work together in order to build an extraordinary, strong, secure, and peaceful future for Bhutan.” ISBN: 978-99936-55-04-6 His Majesty The Druk Gyalpo ISBN: 978-99936-55-05-3 111th National Day, Samtse, 17th December, 2018 TWELVE FIVE YEAR PLAN_BINU_12.indd 3 5/24/2019 10:52:20 AM “Looking ahead, we have a new five-year plan, and a great number of responsibilities of national importance before us. We must work together in order to build an extraordinary, strong, secure, and peaceful future for Bhutan.” His Majesty The Druk Gyalpo 111th National Day, Samtse, 17th December, 2018 TWELVE FIVE YEAR PLAN_BINU_12.indd 3 5/24/2019 10:52:20 AM PRIME MINISTER 2nd February, 2019 FOREWORD e 12th Five Year Plan (FYP) commences amid numerous auspicious occasions that hold special signi cance for all Bhutanese. Our Nation celebrated the 12th year of glorious reign of His Majesty e Druk Gyalpo and 111 years of the institution of Monarchy and nation building. e nation continues to enjoy the blessings of Yabjey-Damba, His Majesty e Fourth Druk Gyalpo. It witnessed the 22nd year of tireless service by His Holiness the 70th Je Khenpo for the wellbeing of the country and its people. e Nation’s Son, His Royal Highness e Gyalsey Jigme Namgyel Wangchuck continues to be a source of unbounded joy for all Bhutanese citizens. -

The Last Shangri-La

THE LAST SHANGRI-LA Paro - Thimpu - Gangtey and Phobjikha - Punakha - Paro 7 Nights / 08 Days Travel Proposal Ref No. 30984 Program Details Day 01: Arrive at Paro / Thimpu (55 Kms / 1 ½ hrs) On arrival, you will be greeted and assisted by our representative and transferred to the hotel. You will receive a Traditional welcome with Tashi Khaddar (White Scarf). Upon arrival in Paro drive to Thimpu. Thimphu – The capital town of Bhutan and the centre of government, religion and commerce, Thimphu is a unique city with unusual mixture of modern development alongside ancient traditions. Although not what one expects from a capital city, Thimphu is still a fitting and lively place. Home to civil servants, expatriates and monk body, Thimphu maintains a strong national character in its architectural style. On arrival in Thimpu, transfer to hotel. Optional: Later in the afternoon, witness / participate in an Archery match wearing Bhutan’s national dress: ‘Gho’ for men & ‘Kira’ for ladies. Archery is the national sport of Bhutan and every village has its own archery range. Using bamboo bows (although modern compound bows are now common in cities) team of archers shoot at targets only 30 centimeters in diameter from a distance of 120 meters. Each team has a noisy crowd of supporters who, as well as encouraging their own side, try to put off the opposition. Archery competition are among the most picturesque and colourful events in the country and are the integral part of all festivities. Dinner & Overnight at the hotel. Meals : Breakfast/Lunch/Dinner Day 02: Thimpu After breakfast, sightseeing in Thimphu valley including visit the following: the National Library (Closed on Saturday & Sunday) housing an extensive collection of priceless Buddhist manuscripts; the Institute for Zorig Chusum (Closed on Saturday & Sunday) (commonly known as the Painting School) where students undergo a 6-year training course in Bhutan’s 13 traditional arts and crafts. -

Said Lhatu Wangchuk. " If We Lose of the Jig Me Singye Wang Chuck National Park

Reinforcing Culture: Tourism in Bhutan by Siok Sian Pek-Dorji From explorers to mountaineers, from environmental specialists to trekkers, from cu lture- hungry adventurers to seven-star jetsetters-Bhutan's tourism continues to evo lve. Today, tourism planners want to ensure that the kingdom's $18 .5 million industry benefits not only the tou r operators, but also the peop le. In 2007, just over 20,000 tourists visited Bhutan-a record . But Bhutan looks beyond numbers. Tou rism is more than a source of hard cu rrency. It is pa rt of Bhutan's journey towa rd development, change, and the enlightened goal of Gross National Happiness. "We see tourism as a means by which we can strengthen our values and our identity," said Lhatu Bhutan's National Museum is housed in the historic Ta Dzong Wangchuk, director general of tourism. "We've become more (watchtower), which is nestled in the hills above Paro Dzong . Its rounded, aware of the value of our own culture and our uniqueness shel l-shaped walls are an impressive accomplishment of seventeenth because of the positive feedback from tourists." century Bhutanese architects and builders. Photo copyright Michael Tobias Based on evaluations from tourists and the experience of the Feedback from tourists has inspired the department to issue past four decades, the tourism department plans to involve the guidelines for the development of infrastructure, facilities, people, especially those from remote communities. In the past, camps ites, and viewpoints. They will be built with traditional cultural enthusiasts and trekkers came into contact only with aesthetics in mind, use local materials and skills, and offer mod tour operators. -

The Road to Change

The Road to Change Annual Report 2019 c d “We are all on the same path, our goals, objectives and dreams, and our future are the same, and we have to work together for it. Let’s hope that wherever we reach is a good place.” —His Majesty The King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck f Table of Contents The Road to Change: Letters from our Co-Chairs and President 2 Health Care Is a Necessity for Bhutan’s Nomadic Communities 8 The Wangduechhoeling Palace: An Evolution to a Cultural and Education Center for Future Bhutanese 12 Changing to Meet Needs in Snow Leopard Conservation 16 Transition Planning: Our Evolving Role in Special Education 20 Project Mikhung: Democracy Is a Verb 24 Steps Toward Food Security and Sustainable Agriculture for Marangdut Community 28 Small Grants, Big Impact 32 Our Partners 38 Bhutan Foundation Grants 42 Financial Overview 46 We Thank Those Who Make It Possible 48 Ways to Give 53 Our Leadership 54 Our Team 56 Contact Us 57 1 The Road to Change and considering all possibilities for Bhutan’s future. Non-governmental organizations (also called civil society organizations) in Bhutan, such as those the Bhutan Foundation supports, will be seen as partners of the government to achieve development goals that further benefit our citizens and our environment. As a country, we have delineated specific objectives to continue our forward movement, including those in the following areas: tourism, cottage and small industry, agriculture and organic farming, employment, governance, public service, private sector, and environmental conservation. As you can see from this partial list, the Bhutan Foundation serves a critical role by supporting capacity-building programs in these and other areas identified as national priorities. -

Bhutan Joint Donor Report 2001

CONTENTS PAGE FOREWORD BY THE RESIDENT REPRESENTATIVE Part I Basic Facts about Bhutan Part II Background Part III An Inventory of Donor Financed Activities in Bhutan I – V Part IV Report Tables Table 1: Summary of the External Assistance by Donor Agency 1 – 3 Table 2: Summary of External Assistance by Type and Implementing Agency 4 – 8 Table 3: Status of the External Assistance Projects in 2000 9 – 42 Table 4: Summary of External Assistance by DAC Codes 42 – 50 Annex I: Acronyms and Abbreviations Annex II: List of DAC-Codes Annex III: Type of Assistance BASIC FACTS ABOUT BHUTAN LAND AREA: 46,500 sq.km GDP PER CAPITA (1996):1 US$ 662 POPULATION (1999) 657,550 Population growth rate (1994): 3.1 % Population density (1999): 14.1 a persons per sq.km Population distribution (1999): Urban: 21% Rural: 79% LAND USE (1999)2 Forest: 72.5% Scrub Forest: 8.1% Agricultural Land: 7.7% Pastures: 3.9% Rock, Snow and Glaciers: 15.7% Other: 0.2% HEALTH Infant mortality rate (1994): 80 per 1000 live births Life expectancy at birth (1994): 66 years Access to Safe drinking water (1999): 63 % Persons per doctor (1999): 6,384 Persons per hospital bed (1999): 1,023 EDUCATION Gross Primary enrolment rate (1999) 72% Number of Schools (1999) 343 1 Source: Central Statistical Organization 2 Source: Land Use Planning Project, Ministry of Agriculture Number of students including institutes (1999) 107,792 Number of teachers including institutes (1999) 2,856 ECONOMY GDP growth rate (1999) 6.0% GDP (1999) (1980 prices): Nu. 3,700 million GDP (1999) (current prices) Nu. -

Myanmar & Bhutan

EARLY BOOKING OVERSEAS CME PRICING PROGRAMS SINCE 2000 REGISTER BY NOV 19, 2018 & SAVE $1,000 / CANADIAN $ PRICING INC AIR COUPLE ! PROFESSIONAL ADVANCEMENT ESCAPE CME & CULTURAL TOUR OF MYANMAR & BHUTAN February 22 - March 10, 2019 The Organizers… Doctors-on-Tour > Doctors-on-Tour was created in 2000 and specializes in offering ecological, cultural, gastronomical and adventure travel to exotic destinations for physicians who want to combine learning and travelling. Our programs offer targeted educational programs offering updates on current topics of interest together with meetings and discussions with local health care representatives to specifically discuss common medical developments in, and challenges facing, the local health care systems in both Canada and the country where the meetings and discussions are being located. This also includes in-depth tours of hospital facilities (both public and private) in order to meet with local medical practitioners and review, and compare, facilities, techniques and practices on a first hand basis. We offer programs in several worldwide locations including to such diverse and intriguing areas as South America (Brazil, Chile/Argentina, Ecuador/Peru), Africa (Kenya/Tanzania, South Africa, Zanzibar, Kilimanjaro climb), India, Bhutan/Myanmar, China, South East Asia (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos & Bali), Bhutan/Myanmar, Malaysia/Singapore, New Zealand and Europe (Eastern Europe, Iceland, Spain). Additional information, including detailed program brochures downloadable in pdf format and recent testimonials, can be found at www.doctorsontour.ca . The company is a licensed retail travel organization under The Travel Industry Act of Ontario thereby affording complete protection of all monies paid prior to departure. (TICO registration no. 50009110). Contact us at - tel: 416-231-8466 toll free: 1-855-DOC-TOUR (362-8687) fax: 1-888-612-1459 e: [email protected] 1 Dr Lorna D'Silva, Mississauga, Ontario > Dr. -

E-Governance and Anti-Corruption in Bhutan: Emerging Roles of Multi-Layered Leaderships

E-Governance and Anti-Corruption in Bhutan: emerging roles of multi-layered leaderships Conference Paper Development Studies Association (DSA) 2020 New Leadership for Global Challenges Panel 42: Digital Development Leadership Atsuko Okuda Research Fellow United Nations University Maastricht Economic and Social Research Institute for Innovation and Technology June 2020 1 Abstract E-governance initiatives are increasingly seen as a vehicle to tackle corruption. However, empirical evidence to help understand the mechanism is scarce, especially among developing countries. This inductive research explores the relationships between e-governance and corruption through compliance as a possible conduit to explain the phenomena. It answers the question of what are the determinants of compliance among government employee users in e-governance implementation. Bhutan is selected as a case study country, as it is perceived as a low corruption country, despite being a least developed country. The research selected 2 e-governance initiatives central to the government's anti-corruption efforts: the Asset Declaration System of the Anti- Corruption Commission and the electronic Public Expenditure Management System of the Ministry of Finance. Data collection was conducted through document analysis, observations, semi- structured interviews of 33 government officials and experts in 2019. The fieldwork resulted in 1) information system descriptions based on document analysis and observations; 2) evidence of compliance among government employee users obtained through semi-structured interviews; and 3) external expert views for data triangulation. The data is analyzed using coding, pattern matching and cross-case synthesis. The paper presents preliminary findings which identify possible determinants of compliance, with focus on multi-layered leaderships. Due to the technical complexity of e-governance systems, existing leaderships seem to play more supportive roles, while IT officials increasingly provide policy and decision-making roles in the case of Bhutan. -

Awesome Tapes from Bhutan | Norient.Com 28 Sep 2021 03:55:01

Awesome Tapes from Bhutan | norient.com 28 Sep 2021 03:55:01 Awesome Tapes from Bhutan INTERVIEW by Hannes Liechti Bhutan is a tiny kingdom in the himalayas and not really known for experimental music. But due to Ed Linton and his net label «Avant-Garbe Records» there is a growing music scene with a love for weird sounds. [Hannes Liechti]: Could you briefly describe yourself and your musical background? [Ed Linton]: From my name you can tell I am not of Bhutan descent, my parents come from New Zealand and spent many years traveling. I was born originally in Bhutan but my father got a dairy farming contract in the Middle East and I lived there for three years before returning. Thebong, where I went to school, has no music stores. So we listened to a lot of foreign music we could get when one of us went to the city. I remember some of the inspirational music we heard. Of course we heard popular music like Queen https://norient.com/blog/awesome-tapes-from-bhutan Page 1 of 4 Awesome Tapes from Bhutan | norient.com 28 Sep 2021 03:55:01 and The Beatles but also older and stranger music, like «20 Jazz Funk Greats» by Throbbing Gristle and «Negrea Love Dub» by Linval Thompson or «Selected Ambient Works 85-92» by Aphex Twin, these are albums that we really enjoyed in school and ended up influencing our music. [HL]: What is the idea behind your band The Columbine Shoots? [EL]: The Columbine Shoots is a band that I started with friends after we finished school in 2013. -

Report of Mountain Echoes 2019

FESTIVAL REPORT 2019 Presented by Jaypee Group An India-Bhutan Foundation Initiative In association with Siyahi AUGUST 22-25, 2019 Thimphu, Bhutan FESTIVAL AT A GLANCE • Mountain Echoes Festival of Art, Literature and Culture is an initiative of the India Bhutan Foundation, in association with Siyahi. The festival is presented by the Jaypee Group. • Bhutan’s annual literary Gathering was held in Thimphu from 23 to 25 AuGust 2019 at Royal University of Bhutan and Taj Tashi with the inaugural on 22nd August at India House. • Rich with words and ideas , centered on the theme Many Lives, Many Stories, showcased stories that explored and celebrated the many elements of personal, professional, mental and spiritual success. • The milestone 10th edition saw a true example of a Global audience with thousands of people from all strata of Indian, International and Bhutanese society. • The festival brouGht toGether writers, bioGraphers, historians, environmentalists, scholars, photographers, poets, musicians, artists, film-makers to enGaGe in a cultural dialoGue, share stories, create memories and spend three blissful days in the mountains. CHIEF ROYAL PATRON OF MOUNTAIN ECHOES Her Majesty the Royal Queen Mother Ashi Dorji WanGmo WanGchuck FESTIVAL DIRECTORS Namita Gokhale Pramod K.G. TsherinG Tashi Kelly Dorji FESTIVAL PRODUCER Mita Kapur FESTIVAL PARTNERS INDIA BHUTAN FOUNDATION was established in AuGust 2003 by the Royal Government of Bhutan and the Government of India with the objective of enhancinG exchanGe and interaction amonG the people of both countries through activities in the areas of education, culture, science and technoloGy. JAYPEE GROUP is a well-diversified infrastructural industrial conglomerate in India.