E-Governance and Anti-Corruption in Bhutan: Emerging Roles of Multi-Layered Leaderships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations Development Programme Project Document

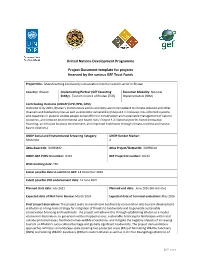

United Nations Development Programme Project Document template for projects financed by the various GEF Trust Funds Project title: Mainstreaming biodiversity conservation into the tourism sector in Bhutan Country: Bhutan Implementing Partner (GEF Executing Execution Modality: National Entity): Tourism Council of Bhutan (TCB) Implementation (NIM) Contributing Outcome (UNDAF/CPD, RPD, GPD): Outcome 4: By 2023, Bhutan’s communities and its economy are more resilient to climate-induced and other disasters and biodiversity loss as well as economic vulnerability (Output 4.1: Inclusive, risk-informed systems and capacities in place to enable people to benefit from conservation and sustainable management of natural resources, and reduced environmental and health risks; Output 4.2: National policies foster innovative financing, an inclusive business environment, and improved livelihoods through climate-resilient and nature- based solutions) UNDP Social and Environmental Screening Category: UNDP Gender Marker: Moderate 2 Atlas Award ID: 00094492 Atlas Project/Output ID: 00098610 UNDP-GEF PIMS ID number: 6319 GEF Project ID number: 10234 LPAC meeting date: TBC Latest possible date to submit to GEF: 14 December 2020 Latest possible CEO endorsement date: 14 June 2021 Planned start date: July 2021 Planned end date: June 2026 (60 months) Expected date of Mid-Term Review: March 2024 Expected date of Terminal evaluation: May 2026 Brief project description: This project seeks to mainstream biodiversity conservation into tourism development in Bhutan as a long-term strategy for mitigation of threats to biodiversity and to generate sustainable conservation financing and livelihoods. The project will achieve this through establishing Bhutan as a model ecotourism destination, to generate livelihood opportunities, sustainable financing for landscapes within and outside protected areas, facilitate human-wildlife coexistence, and mitigate the negative impacts of increasing tourism on Bhutan’s socio-cultural heritage and globally significant biodiversity. -

Black-Necked Crane Conservation Action Plan for Bhutan (2021 - 2025)

BLACK-NECKED CRANE CONSERVATION ACTION PLAN FOR BHUTAN (2021 - 2025) Department of Forests and Park Services Ministry of Agriculture and Forests Royal Government of Bhutan in collaboration with Royal Society for Protection of Nature Plan prepared by: 1. Jigme Tshering, Royal Society for Protection of Nature 2. Letro, Nature Conservation Division, Department of Forests and Park Services 3. Tandin, Nature Conservation Division, Department of Forests and Park Services 4. Sonam Wangdi, Nature Conservation Division, Department of Forests and Park Services Plan reviewed by: 1. Dr. Sherub, Specialist, Ugyen Wangchuck Institute for Conservation and Environmental Research, Department of Forests and Park Services. 2. Rinchen Wangmo, Director, Program Development Department, Royal Society for Protection of Nature. Suggested citation: BNC 2021. Black-necked Crane Conservation Action Plan (2021-2025), Department of Forests and Park Services, Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, and Royal Society for Protection of Nature, Thimphu, Bhutan དཔལ་辡ན་འབྲུག་ག筴ང་། སོ་ནམ་དང་ནགས་ཚལ་辷ན་ཁག། ནགས་ཚལ་དང་ག콲ང་ཀ་ཞབས་ཏོག་ལས་ݴངས། Royal Government of Bhutan Ministry of Agriculture and Forests Department of Forests and Park Services DIRECTOR Thimphu MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR The Department of Forests and Park Services has been mandated to manage and conserve Bhutan's rich biodiversity. As such the department places great importance in the conservation of the natural resources and the threatened wild fauna and flora. With our consistent conservation efforts, we have propelled into the 21st century as a champion and a leader in environmental conservation in the world. The conservation action plans important to guide our approaches towards conserving the species that are facing considerable threat. -

6 Dzongs of Bhutan - Architecture and Significance of These Fortresses

6 Dzongs of Bhutan - Architecture and Significance of These Fortresses Nestled in the great Himalayas, Bhutan has long been the significance of happiness and peace. The first things that come to one's mind when talking about Bhutan are probably the architectures, the closeness to nature and its strong association with the Buddhist culture. And it is just to say that a huge part of the country's architecture has a strong Buddhist influence. One such distinctive architecture that you will see all around Bhutan are the Dzongs, they are beautiful and hold a very important religious position in the country. Let's talk more about the Dzongs in Bhutan. What are the Bhutanese Dzongs? Wangdue Phodrang Dzong in Bhutan (Source) Dzongs can be literally translated to fortress and they represent the majestic fortresses that adorn every corner of Bhutan. Dzong are generally a representation of victory and power when they were built in ancient times to represent the stronghold of Buddhism. They also represent the principal seat for Buddhist school responsible for propagating the ideas of the religion. Importance of Dzongs in Bhutan Rinpung Dzong in Paro, home to the government administrative offices and monastic body of the district (Source) The dzongs in Bhutan serve several purposes. The two main purposes that these dzongs serve are administrative and religious purposes. A part of the building is dedicated for the administrative purposes and a part of the building to the monks for religious purposes. Generally, this distinction is made within the same room from where both administrative and religious activities are conducted. -

2008 Smithsonian Folklife Festival

Smithsonian Folklife Festival records: 2008 Smithsonian Folklife Festival CFCH Staff 2017 Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 600 Maryland Ave SW Washington, D.C. [email protected] https://www.folklife.si.edu/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents note................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 2 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Program Books, Festival Publications, and Ephemera, 2008................... 6 Series 2: Bhutan: Land of the Thunder Dragon....................................................... 7 Series 3: NASA: Fifty Years and Beyond............................................................. -

A Bhutanese Perspective on First

Assessing the First Decade of the World’s Indigenous People (1995-2004): Volume II - The South Asia Experience Tebtebba Foundation Copyright © TEBTEBBA FOUNDATION, 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of the copyright owner and the publisher. The views expressed by the writers do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher. Published by Tebtebba Foundation No. 1 Roman Ayson Road 2600 Baguio City Philippines Tel. +63 74 4447703 * Tel/Fax: +63 74 4439459 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.tebtebba.org Writers: Sanjaya Serchan, Om Gurung, Raja Devasish Roy, Sanjeeb Drong, Mangal Kumar Chakma, Françoise Pommaret, Dawa Lhamo, Walter Fernandes, Gita Bharali, Vemedo Kezo, Joseph Marianus Kujur, T. A. John and The Center for Biodiversity and Indigenous Knowledge, Yunnan, China Editor: Arellano Colongon, Jr. Copy Editor: Raymond de Chavez Cover Design, Lay-out and Production: Paul Michael Q. Nera & Raymond de Chavez Assistant: Marly Cariño Printed in the Philippines by Valley Printing Specialist Baguio City, Philippines ISBN: 978-971-0186-06-8 ii Assessing the First Decade of the World’s Indigenous People (1995-2004) The South East Asia Experience Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t s Acronyms ..................................................................... vi Overview ....................................................................... 1 Volume II: South Asia Case Studies .............................. 51 1 Indigenous Peoples in Nepal: An Assessment of the UN International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People (1995-2004) ............................................... 53 2 An Assessment of the United Nations First International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People in Bangladesh ............................................. -

Deconstructing Androcentrism in Buddhist Literature Through the Lens of Ethnography: a Case Study of Bhutanese Nuns

KEMANUSIAAN Vol. 25, Supp. 1, (2018), 143–165 Deconstructing Androcentrism in Buddhist Literature Through the Lens of Ethnography: A Case Study of Bhutanese Nuns *SONAM WANGMO JULI EDO KAMAL SOLHAIMI FADZIL Department of Anthropology and Sociology, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia *Corresponding author: [email protected] Published online: 20 December 2018 To cite this article: Wangmo, S., Edo, J. and Fadzil, K.S. 2018. Deconstructing androcentrism in Buddhist literature through the lens of ethnography: A case study of Bhutanese nuns. KEMANUSIAAN the Asian Journal of Humanities 25(Supp. 1): 143–165, https://doi.org/10.21315/ kajh2018.25.s1.8 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.21315/kajh2018.25.s1.8 Abstract. Traditional androcentric sociology has reinforced biased views of women and portrayed women as silent research objects of minor importance that figure marginally in academic writing, thereby distorting the knowledge base. The same tendencies have been observed in Buddhist religious literature. The bone of contention in the feminist critique of Buddhism is the omission of women from religious literature. Although Buddhist women’s spiritual prowess was well documented in early Buddhism in religious literature such as the Therīgatha, later Buddhist literature began to demonstrate androcentric tendencies, in most instances completely ignoring the religious lives of women. Since women have been largely sidelined in Buddhist texts, it is important to go beyond textual dimensions to gain deeper insights into women’s religious lives. The feminist Buddhist scholar, Rita Gross (2009), in her monumental work, A Garland of Feminist Reflections, emphasised the need to explore various ways other than our own to think, live and practice religion to broaden our horizons to avoid a narrow-minded approach to academic research. -

United Nations Bhutan Covid-19 Sitrep #3

BRIEF UNITED NATIONS BHUTAN COVID-19 SITREP #3 UPDATE 30 July 2020 Highlight of Key UN Achievements and Advocacy Messages Given the scale of this global COVID challenge, our world may need to go beyond simple categories of either optimism or pessimism. UN Bhutan is responding to the immediate needs of the people; the needs of the most vulnerable while strengthening economic resilience and building longer-term human capital in a comprehensive way so that we find new ways to ‘Build Back Better’. - Gerald Daly, UN Resident Coordinator, Bhutan One UN The Government of Bhutan is closely monitoring the coronavirus pandemic and while 101 cases have been confirmed in Bhutan, all were imported, and no deaths have been reported. While the health impact has so far been limited as compared to many other countries, the economic and social effects are significant. The health sector would be challenged to cope with a major outbreak and a possible stock out of essential health commodities such as drugs, reagents and consumables. An extended period of limited movement of people, goods, and finances will have important consequences for the economy, especially the tourism sector and related service industries. Bhutan is also likely to be negatively affected by any extended economic downturn in its neighbors (especially India). The UN in Bhutan (FAO, IFAD, ITC, UNDP, UNESCAP, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNICEF, UNODC, WFP, and WHO) moved quickly and pro-actively to respond to COVID-19. In particular, UN agencies developed a joint response framework aligned with “UN Framework for the Socio-Economic Response to COVID-19” includes both short-term measures to mitigate negative social and economic consequences along with medium- to long-term investments to strengthen the re-build and resilience to future crises. -

Monthly E-Newsletter of the Embassy of India, Thimphu

9/7/2020 BILATERAL: Covid-19 RT-PCR test kits to Bhutan | elink Monthly E-Newsletter of the Embassy of India in Thimphu AUGUST 2020 September 3, 2020 Dear Reader, I am delighted to present the {rst monthly e-newsletter of the Embassy of India in Thimphu! This newsletter will capture our activities in Bhutan, key developments in India and of course, heart- warming stories of community and companionship. August is, of course, a special month for us as we celebrated India's 74th Independence Day. The warm messages we received from Bhutan are an indication of the strong bonds we share, not just at the political level, but also at a personal one. The Government of India launched a slew of development initiatives in August 2020 in the areas of education, agriculture, taxation, and health, all aimed at helping India achieve self- reliance: ‘Aatma Nirbhar Bharat’. We hope you enjoy reading this {rst edition of our monthly e-newsletter. Tashi Delek! Jai Hind! - Ruchira Kamboj, Ambassador of India to Bhutan https://elink.io/p/india-in-bhutan-984c310 1/18 9/7/2020 BILATERAL: Covid-19 RT-PCR test kits to Bhutan | elink indembthimphu.gov.in BILATERAL: Covid-19 RT-PCR test kits to Bhutan 17 August 2020: The Government of India handed over the 6th consignment of medical supplies with 20,000 Covid-19 RT-PCR tests to the Royal Government of Bhutan, at Phuentsholing, to assist Bhutan in {ghting the Covid-19 pandemic. Going forward, India will continue to extend all possible support to Bhutan to minimize the health and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. -

Technical Review and Social Impact Assessment

Technical Review and Social Impact Assessment Reducing Climate Change-induced Risks and Vulnerabilities from Glacial Lake Outburst Floods in the Punakha, Wangdue and Chamkhar Valleys UN House Tel: +975-2-322424 Fax: +975-2-328526, 322657 P.O Box 162 Email: [email protected] Thimphu, Bhutan www.undp.org.bt GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY INVESTING IN OUR PLANET November 2012 Copyright © United Nations Development Programme, 2012 United Nations Development Programme UN House, P.O. Box 162 Samten Lam Thimphu : Bhutan http://www.undp.org.bt Printed by: KUENSEL Coporation Ltd Contents List of Figures and Tables 2 Acronyms 3 Glossary of Dzongkha Terms 5 Acknowledgements 6 Executive Summary 7 1. Introduction 14 2. Methodology 16 3. Artificial Lowering of Thorthormi Lake (Outcome 2) 18 4. GLOF Early Warning System (Outcome 3) 34 5. Community Based Disaster Risk Management approach (Outcome 1& 3) 46 6. Documentation and Dissemination (Outcome 4) 54 7. Lessons Learned from Adaptive Management 56 8. Formulation of an exit-strategy for the project 58 9. Recommendations for replication and scaling-up of project interventions in Bhutan and other GLOF-prone countries 61 10. Key findings and Recommendations 64 11. References reviewed 66 Appendices 1. ToR 69 2. Questionnaire Formats 74 3. Itinerary 78 4. List of People Met/Interviewed 81 5. Interview/Focus Group Discussion Transcripts 85 6. Transcripts of the Consultative Meetings in Thimphu 99 Technical Review and Social Impact Assessment - GLOF Project List of Figures and Tables Figure 1 The main source area of Thorthormi glacier on the south slope of Singye Kang 4 or Table mountain Figure 2 Panoramic overview of Thorthormi Glacier from the left lateral moraine. -

Impact of Climate on Rural Communities in Bhutan Climate Change Reporting: Impact of Climate on Rural Communities in Bhutan

Climate Change Reporting: Impact of Climate on Rural Communities in Bhutan Climate Change Reporting: Impact of Climate on Rural Communities in Bhutan Climate Change Reporting: Impact of Climate on Rural Communities in Bhutan | 1 | Contents Haaps fear extinction of yak herding practice 24 Conserving water resources with PES, an example from Yakpugang 33 Trading White Gold 36 Background Selected grantees with the mentors for A fungus, A Community and 05 Climate Change Reporting Grant Features its Culture 39 Water shortage a national The lost mandarin growers concern 07 of Bhutan 44 Pangtse shing benefits rural communities but faces threat 11 from deforestation Containing our glacier-lake 15 ticking time bombs Danger of wrathful waters 21 in Lhuentse ᭴་讐་蝴ན་བ讟ན་གནས་ཐབས་轴་ སྤྱོད་འ䍴ས་ལམ་轴གས་ག筲་བ杴གས། | 2 | Climate Change Reporting: Climate Change Reporting: | 3 | Impact of Climate on Rural Communities in Bhutan ༢༩ Impact of Climate on Rural Communities in Bhutan Background >> Selected grantees with the mentors for Climate Change Reporting Grant Bhutan Media Foundation (BMF) completed its first round of Climate Change Reporting (CCR) Grant within the period of four months from August to November, 2020. The main objective of CCR Grant is to produce well-researched, in-depth stories on the impact of climate change on vulnerable rural communities of Bhutan. The grant has sent the eight reporters across the length and breadth of the country pursuing various climate change stories. Travelling across rural Bhutan is always challenging. This year, it was made worse by travel restrictions due to COVID-19. Yet, the reporters persevered and the result is a critical mass of stories climate change stories. -

Development and Its Impacts on Traditional Dispute Resolution in Bhutan

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 63 New Directions in Domestic and International Dispute Resolution 2020 Formalizing the Informal: Development and its Impacts on Traditional Dispute Resolution in Bhutan Stephan Sonnenberg Seoul National University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons Recommended Citation Stephan Sonnenberg, Formalizing the Informal: Development and its Impacts on Traditional Dispute Resolution in Bhutan, 63 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 143 (2020), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol63/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FORMALIZING THE INFORMAL: DEVELOPMENT AND ITS IMPACTS ON TRADITIONAL DISPUTE RESOLUTION IN BHUTAN Stephan Sonnenberg* INTRODUCTION Bhutan is a small landlocked country with less than a million inhabitants, wedged between the two most populous nations on earth, India and China.1 It is known for its stunning Himalayan mountain ranges and its national development philosophy of pursuing “Gross National Happiness” (GNH).2 This paper argues, however, that Bhutan should also be known for its rich heritage of traditional dispute resolution. That system kept the peace in Bhutanese villages for centuries: the product of Bhutan’s unique history and its deep (primarily Buddhist) spiritual heritage. Sadly, these traditions are today at risk of extinction, victims—it is argued below—of Bhutan’s extraordinary process of modernization. -

The Executive

The Executive VOLUME I NOVEMBER 7, 2018 - NOVEMBER 7, 2019 YEAR IN OFFICE Laying foundation for change 1,000 Golden Days Plus Digital transformation Removal of “cut Teachers, the Narrowing gap Densa Meet: off” for Class X highest paid civil through pay the other servant revision Mines and Cabinet Minerals Bill AM with PM: Getting to know Revising Tourism policy 9 better Tariff revision Private sector Policies development approved committee Laying foundation for change “Climb higher on the shoulders of past achievements - your task is not to fill old shoes or follow a well-trodden path, but to forge a new road leading towards a brighter future.” His Majesty The King Royal Institute of Management August 9, 2019 Contents • Introduction 8 • From the Prime Minister 10 • Initiating change 13 • Country before party 14 • Revisiting our vision 15 • The 12th Plan is critical 18 • The Nine Thrusts 19 • Densa, the other Cabinet 22 • High value, low volume tourism 22 • More focus on health and education 24 • AM with PM: A dialogue with the Prime Minister 25 • Investing in our children 26 • Pay revised to close gap 27 • Rewarding the backbone of education 28 • Taking APA beyond formalities 29 • Block grant empowers LG 30 • Major tax reforms 30 • TVET transforms 31 • Cautious steps in hydro 32 • Encouraging responsible journalism 32 • Private sector-led economy 33 • Meeting pledges 34 • Policies Approved 36 • Guidelines reviewed and adopted 37 • Overhauling health 38 • A fair chance for every Bhutanese child 41 • Education comes first 42 • Grateful