D.Sc THROUGHOUT Western Renfrewshire the Rocks Exposed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gourock-Dunoon Ferry Service: Feasibility Study of a Future Passenger and Vehicle Service with the Vehicle Portion Being Non-Subsidised

PROJECT Gourock-Dunoon Ferry Service: Feasibility Study of a Future Passenger and Vehicle Service with the Vehicle Portion being non-Subsidised Funding: National (United Kingdom) Duration: Nov 2012 - Jul 2013 Status: Complete with results Background & policy context: Until July 2011, Cowal Ferries operated a passenger and vehicle ferry service across the Firth of Clyde between Gourock and Dunoon town centres. Since then, the Argyll Ferries town centre service has carried foot-passengers only, the service being provided by two passenger ferries. The Gourock-Dunoon route is the busiest ferry crossing in Scotland and the two existing ferry services (Argyll Ferries and Western Ferries’ passenger and vehicle service) provide a key link between Cowal / Dunoon and the central belt. Objectives: In November 2012 MVA Consultancy, together with The Maritime Group (International) Limited, were commissioned by Transport Scotland to carry out a feasibility study on future ferry services between Dunoon and Gourock town centres. The overarching aim of the study was to determine the feasibility of a service with the vehicle-carrying portion of the service operating without subsidy and the passenger- carrying portion being subsidised in a manner compatible with EU law. Other funding sources: Transport Scotland Organisation: Transport Scotland Key Results: There are a range of key potential 'upside' aspects (eg lower vessel GT, pier & berthing dues reduced through negotiation, Western Ferries retrenchment) and 'downside' aspects (eg higher GT, higher crewing levels and competitive response from Western Ferries) which could affect the service and the balance of these would be crucial in determining the ultimate feasibility of the town centre passenger and vehicle service. -

Wed 12 May 2021

Renfrewshire Golf Union - Wed 12 May 2021 County Seniors Championship - Kilmacolm Time Player 1 Club CDH Player 2 Club CDH Player 3 Club CDH 08:00 Graham McGee Kilmacolm 4000780479 James Hope Erskine 4000783929 Keith Stevenson Paisley 4000988235 08:09 Richard Wilkes Cochrane Castle 4000782540 Brian Kinnear Erskine 4000781599 Iain MacPherson Paisley 4000986701 08:18 Bruce Millar Cochrane Castle 4001363171 Keith Hunter Cochrane Castle 4002416751 John Jack Gourock 4001143810 08:27 Morton Milne Old Course Ranfurly 4001317614 Alistair MacIlvar Old Course Ranfurly 4001318753 Stephen Woodhouse Kilmacolm 4002182296 08:36 Gregor Wood Erskine 4002996989 James fraser Paisley 4000986124 Mark Reuben Kilmacolm 4000973292 08:45 Iain White Elderslie 4000874290 Patrick McCaughey Elderslie 4001567809 Gerry O'Donoghue Kilmacolm 4001584944 08:54 Steven Smith Paisley 4000983616 Garry Muir Paisley 4000987488 David Pearson Greenock Whinhill 4002044829 09:03 Nairn Blair Elderslie 4003056142 Alex Roy Greenock 4001890868 Mitchell Ogilby Greenock Whinhill 4002044801 09:12 Brian Fitzpatrick Greenock 4002046021 William Boyland Kilmacolm 4001584434 Peter McFadyen Greenock Whinhill 4002225289 09:21 James Paterson Ranfurly Castle 4001000546 Ian Walker Elderslie 1000125227 Matthew McCorkell Greenock Whinhill 4002044608 09:30 Chris McGarrity Paisley 4000987044 Michael Mcgrenaghan Cochrane castle 4001795367 Archie Gibb Paisley 4000986153 09:39 Ian Pearston Cochrane Castle 4001795691 Patrick Tinney Greenock 4001890490 Les Pirie Kilmacolm 4002065824 09:48 Billy Anderson -

901, 904 906, 907

901, 904, 906 907, 908 from 26 March 2012 901, 904 906, 907 908 GLASGOW INVERKIP BRAEHEAD WEMYSS BAY PAISLEY HOWWOOD GREENOCK BEITH PORT GLASGOW KILBIRNIE GOUROCK LARGS DUNOON www.mcgillsbuses.co.uk Dunoon - Largs - Gourock - Greenock - Glasgow 901 906 907 908 1 MONDAY TO SATURDAY Code NS SO NS SO NS NS SO NS SO NS SO NS SO NS SO Service No. 901 901 907 907 906 901 901 906X 906 906 906 907 907 906 901 901 906 908 906 901 906 Sandbank 06.00 06.55 Dunoon Town 06.20 07.15 07.15 Largs, Scheme – 07.00 – – Largs, Main St – 07.00 07.13 07.15 07.30 – – 07.45 07.55 07.55 08.15 08.34 08.50 09.00 09.20 Wemyss Bay – 07.15 07.27 07.28 07.45 – – 08.00 08.10 08.10 08.30 08.49 09.05 09.15 09.35 Inverkip, Main St – 07.20 – 07.33 – – – – 08.15 08.15 – 08.54 – 09.20 – McInroy’s Point 06.10 06.10 06.53 06.53 – 07.24 07.24 – – – 07.53 07.53 – 08.24 08.24 – 09.04 – 09.29 – Gourock, Pierhead 06.15 06.15 07.00 07.00 – 07.30 07.30 – – – 08.00 08.00 – 08.32 08.32 – 09.11 – 09.35 – Greenock, Kilblain St 06.24 06.24 07.10 07.10 07.35 07.40 07.40 07.47 07.48 08.05 08.10 08.10 08.20 08.44 08.44 08.50 09.21 09.25 09.45 09.55 Greenock, Kilblain St 06.24 06.24 07.12 07.12 07.40 07.40 07.40 07.48 07.50 – 08.10 08.12 08.12 08.25 08.45 08.45 08.55 09.23 09.30 09.45 10.00 Port Glasgow 06.33 06.33 07.22 07.22 07.50 07.50 07.50 – 08.00 – 08.20 08.22 08.22 08.37 08.57 08.57 09.07 09.35 09.42 09.57 10.12 Coronation Park – – – – – – – 07.58 – – – – – – – – – – – – – Paisley, Renfrew Rd – 06.48 – – – – 08.08 – 08.18 – 08.38 – – 08.55 – 09.15 09.25 – 10.00 10.15 10.30 Braehead – – – 07.43 – – – – – – – – 08.47 – – – – 09.59 – – – Glasgow, Bothwell St 07.00 07.04 07.55 07.57 08.21 08.21 08.26 08.29 08.36 – 08.56 08.55 09.03 09.13 09.28 09.33 09.43 10.15 10.18 10.33 10.48 Buchanan Bus Stat 07.07 07.11 08.05 08.04 08.31 08.31 08.36 08.39 08.46 – 09.06 09.05 09.13 09.23 09.38 09.43 09.53 10.25 10.28 10.43 10.58 CODE: NS - This journey does not operate on Saturdays. -

Renfrewshire Council

RENFREWSHIRE COUNCIL SUMMARY OF APPLICATIONS TO BE CONSIDERED BY THE PLANNING & PROPERTY POLICY BOARD ON 08/11/2016 APPN. NO: WARD: APPLICANT: LOCATION: PROPOSAL: Item No. 16/0655/PP Arora Management Former Clansman Club, Erection of part single A1 Services Limited Abbotsinch Road, Paisley storey, part two storey Ward 4: Paisley immigration holding North West facility (Class 8) with associated access, hard standing, fence, gate RECOMMENDATION: GRANT subject to conditions and landscaping 16/0639/PP Robertson Homes Land at North West end Erection of residential A2 Limited of, King's Inch Road, development Ward1: Renfrew Renfrew comprising 120 flats North with associated roads, drainage and landscaping RECOMMENDATION: GRANT subject to conditions 16/0612/PP Keepmoat Homes & Site on South Eastern Erection of residential A3 Clowes Development boundary of junction with development Ward 4: Paisley Fleming Street, New comprising 116 North West Inchinnan Road, Paisley dwellinghouses and 66 flats including roads, footpaths, open space RECOMMENDATION: GRANT subject to conditions and associated works. 16/0644/PP SC TS Scotland Football Ground, St Regulation 11 renewal A4 Limited Mirren Football Club, application of approval Ward 4: Paisley Love Street, Paisley, PA3 13/0431/PP, for North West 2EA residential development with associated car parking, landscaping RECOMMENDATION: Disposed to grant and vehicular and pedestrian access (in principle). 16/0423/PP Paterson Partners Site at Whitelint Gate, Erection of a retail store A5 Johnstone Road, Bridge including new access, Ward 9: Houston, of Weir petrol filling station and Crosslee, Linwood cycle hub. (Planning and permission in principle) Ward 10: Bishopton, BoW, Langbank RECOMMENDATION: Refuse Printed: 31/10/2016 Page 1 of 2 APPN. -

1 Rugged Upland Farmland

SNH National Landscape Character Assessment Landscape Character Type 202 RUGGED UPLAND FARMLAND Location and Context The Rugged Upland Farmland Landscape Character Type, which shares many of the attributes of Plateau Farmland – Glasgow & Clyde Valley, is found in Kilmacolm, Johnstone and Neilston. It occurs in lnverclyde, Renfrewshire and East Renfrewshire local authority areas, north and west of Newton Mearns, where the smooth plateau farmlands and higher plateau moorlands give way to a more rugged farmland landscape, forming a transition to the rugged moorland area further north west. Key Characteristics Rugged landform comprising rocky bluffs and shallow troughs. Reservoirs in flooded troughs. Dominance of pastoral farming. Frequent tree cover often emphasising landform, for example concentrated on bluffs and outcrops. Settlement limited to farms and villages. Landscape Character Description Landform The Rugged Upland Farmland landscapes are, for the large part underlain by millstone grits and carboniferous limestone with peripheral, higher areas of basalt. They are characterised, to a greater or lesser degree, by a rugged, hummocky landscape of steep, craggy bluffs interspersed with gentler farmland. Many of the troughs and valleys are flooded, providing reservoirs for urban areas to the north. The area south of Gleniffer Braes is more gentle and plateau-like. Landcover Woodland cover is relatively extensive, providing an important structural element, with many of the rugged hillocks covered in stands of beech or pine. The more hospitable areas are mostly improved pasture (mainly given over to sheep farming). Beech hedgerow trees are a 1 SNH National Landscape Character Assessment LCT 202 RUGGED UPLAND FARMLAND distinctive feature in many parts of this landscape, often associated with past estates. -

Provided Please Contact: SPT Bus Operations 131 St. Vincent St

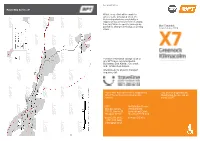

Ref. W065E/07/19 Route Map Service X7 Whilst every effort will be made to adhere to the scheduled times, the Partnership disclaims any liability in respect of loss or inconvenience arising from any failure to operate journeys as Bus Timetable published, changes in timings or printing From 14 July 2019 errors. For more information visit spt.co.uk or any SPT travel centre located at Buchanan, East Kilbride, Greenock and Hamilton bus stations. Alternatively, for all public transport enquiries, call: If you have any comments or suggestions This service is operated by about the service(s) provided please McGill’s Bus Service Ltd on contact: behalf of SPT. SPT McGill’s Bus Service Bus Operations 99 Earnhill Rd 131 St. Vincent St Larkfield Ind. Estate Glasgow G2 5JF Greenock PA16 0EQ t 0345 271 2405 t 08000 515 651 0141 333 3690 e [email protected] Service X7 Greenock – Kilmacolm Operated by McGill’s Bus Service Ltd on behalf of SPT Route Service X7: From Greenock, Kilblain Street, via High Street, Dalrymple Street, Rue End Street, Main Street, East Hamilton Street, Port Glasgow Road, Greenock Road, Brown Street, Shore Street, Scarlow Street, Fore Street, Greenock Road, Glasgow Road, Clune Brae, Kilmacolm Road, Dubbs Road, Auchenbothie Road, Marloch Avenue, Kilmacolm Road, A761, Port Glasgow Road, to Kilmacolm Cross. Return from Kilmacolm Cross via Port Glasgow Road, A761, Kilmacolm Road, Marloch Avenue, Auchenbothie Road, Dubbs Road, Kilmacolm Road, Clune Brae, Glasgow Road, Greenock Road, Fore Street, Scarlow Street, Shore Street, Brown Street, Greenock Road, Port Glasgow Road, East Hamilton Street, Main Street, Rue End Street, Dalrymple Street, High Street to Greenock, Kilblain Street Monday to Saturday Greenock, Kilblain Street 1800 1900 2000 2100 ... -

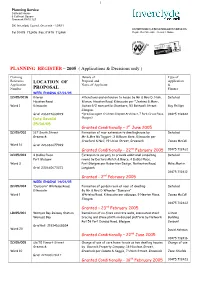

PLANNING REGISTER – 2005 ( Applications & Decisions Only )

1 Planning Service Cathcart House 6 Cathcart Square Greenock PA15 1LS DX: Inverclyde Council, Greenock - 1,GR11 ENVIRONMENT & REGENERATION SERVICES Tel 01475 712406 Fax: 01475 712468 Depute Chief Executive : Gerard J. Malone PLANNING REGISTER – 2005 ( Applications & Decisions only ) Planning Details of Type of Reference LOCATION OF Proposal and Application Application Name of Applicant & Number PROPOSAL Planner WEEK ENDING 07/01/05 IC/05/001R Kiloran Alterations and extension to house by Mr & Mrs D. Nish, Detailed Houston Road Kiloran, Houston Road, Kilmacolm per *Jenkins & Marr, Ward 1 Kilmacolm Suites 5/2 mercantile Chambers, 53 Bothwell Street, Guy Phillips Glasgow. Grid: 236377669079 *(previous agent Crichton Simpson Architect, 7 Park Circus Place, 01475 712422 Date Revalid Glasgow) 25/04/05 Granted Conditionally – 1st June 2005 IC/05/002 167 South Street Formation of rear extension to dwellinghouse by Detailed Greenock Mr & Mrs McTaggart, 3 Gillburn Gate, Kilmacolm per Crawford & Neil, 19 Union Street, Greenock James McColl Ward 16 Grid: 226336677029 Granted Conditionally - 22nd February 2005 01475 712462 IC/05/003 4 Dubbs Place Extension to surgery to provide additional consulting Detailed Port Glasgow rooms by Doctors Mutch & Boyce, 4 Dubbs Place, Ward 3 Port Glasgow per Robertson Design, Netherton Road, Mike Martin Grid: 233660673371 Langbank 01475 712412 nd Granted - 2 February 2005 WEEK ENDING 14/01/05 IC/05/004 “Duncairn” Whitelea Road, Formation of garden room at rear of dwelling Detailed Kilmacolm By Mr & Mrs D Wheeler “Duncairn” -

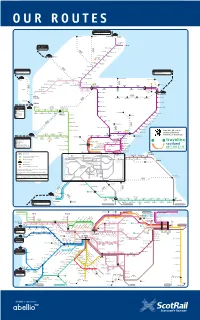

Scan This QR Code to Download the Free Traveline Scotland

OUR ROUTES Ferry destinations from Scrabster :- Stromness (Orkney) Durness Tongue Scrabster Thurso Georgemas Junction Ferry destination Wick from Ullapool:- Altnabreac Stornoway (Lewis) Scotscalder Kinbrace Forsinard Helmsdale Ullapool Kildonan Dunrobin Castle Brora Rogart Golspie Invershin Lairg Ferry destinations from Uig :- Ardgay Culrain Ferry destinations from Aberdeen :- Lochmaddy (North Uist) Tarbert (Harris) Kirkwall (Orkney) Fearn Lerwick (Shetland Islands) Tain Alness Achanalt Garve Invergordon Lossiemouth Uig Fraserburgh Achnasheen Lochluichart Dingwall Strathcarron Achnashellach Peterhead Conon Bridge Inverness Forres Keith Insch Dyce Stromeferry Attadale Skye Duirinish Nairn Elgin Huntly Inverurie Duncraig Muir of Beauly Aberdeen Ord Carrbridge Airport Plockton Aberdeen Kyle of Aviemore Portlethen Lochalsh Braemar Ballater Aboyne Banchory Armadale Kingussie Stonehaven Mallaig Loch Eil Newtonmore Ferry destinations Morar Laurencekirk from Mallaig:- Outward Spean Roy Beasdale GlenfinnanBound Banavie Bridge Bridge Canna Castlebay (Barra) Dalwhinnie Eigg Kirriemuir Lochboisdale Arisaig Lochailort Locheilside Corpach Fort Montrose (South Uist) William Tulloch Forfar Muck Blair Atholl Arbroath Rum Corrour Carnoustie Pitlochry Golf Street Rannoch Blairgowrie Barry Links Bridge of Orchy Monifieth Dunkeld & Birnam Balmossie Upper Tyndrum Scan this QR code to Invergowrie Tyndrum Dundee Broughty Ferry download the free Taynuilt Loch Awe Lower Traveline Scotland app Dunblane Gleneagles Perth Leuchars St Andrews Callander Crianlarich Ferry -

Paisley and Clyde Cycling Path

Part of the This route is a partnership between National Cycle Network This 20 mile cycleway and footpath forms part of the Clyde to Forth National Cycle Route. It starts at Paisley Canal Railway Station, and ends in Gourock at the Railway Station and ferry terminal. Along the way it passes the town of Johnstone and crosses attractive open country between Bridge of Weir and Kilmacolm, before reaching Port Glasgow and Greenock on the Firth of Clyde. manly' traffic-free path far cyclists Ferries ply between Gourock and Duncan, a gateway to the The National Cycle Network is a comprehensive network Argyll area of the Loch Lomond and The Trossachs of safe and attractive routes to cycle throughout the UK. National Park. The route is mainly traffic-free apart from 10,000 miles are due for completion by 2005, one third of which will be on traffic-free paths, the rest will follow quiet short sections through Elderslie and kilmalcolm . There are lanes or traffic-calmed roads. It is delivered through the some steep gradients in Port Glasgow and Greenock . policies and programmes of over 450 local authorities and There is wheelchair access to the whole route. other partners, and is co-ordinated by the charity Sustrans. Sustrans - the sustainable transport charity - works on practical projects to encourage people to walk, cycle and www.nationalcyclenetwork.org.uk use public transport in order to reduce motor traffic and its adverse effects. 5,000 miles of our flagship project, the For more information on routes in your area: National Cycle Network, were officially opened in June 0845 113 0065 2000, we will increase this to 10,000 miles by 2005. -

KCC Minute 2017-03-28 Approved Version

KILMACOLM COMMUNITY COUNCIL Minute of Meeting: Tuesday 28 March 2017 Kilmacolm Community Council Meeting Tuesday 28 March 2017 at 7.30pm in Room 205 Kilmacolm Community Centre Present: Mike Jefferis – Chair Helen Cook – Vice Chair David Goddard – Secretary Jan Johnston - Treasurer Alda Clark Edwin Fisher Helen MacConnacher Cllr James McColgan - Ex Officio Member Cllr David Wilson - Ex Officio Member Attending: PC John Jamieson - Police Scotland; Margie McCallum; Christopher Corley Apologies: David Madden, Dale McFadzean, Jim MacLeod - Ex Officio Member, Cllr Stephen McCabe – Ex Officio Member, Ronnie Cowan MP - Ex Officio Member 1. Welcome The Chair opened the March 2017 meeting of the Kilmacolm Community Council and welcomed those attending. 2. Minute of the Kilmacolm Community Council Meeting – 31 January 2017 The minute of the 31 January 2017 meeting was approved. 3. Police Scotland PC Jamieson reported on the crimes in Kilmacolm and Quarriers Village area that had been recorded in March 2017. These included a case of driving an uninsured vehicle, an act of vandalism on a motor vehicle, a breach of the peace, a drunken driving offence, a break-in at the Pullman Tavern and incidents concerning St Columba's School. 4. Kilmacolm Community Council Finances Prior to the meeting the Secretary had circulated to the community councillors a copy of the approved 2016/2017 Budget together with a Approved at the 25 April 2017 Meeting of the Kilmacolm Community Council Page !1 of !5 KILMACOLM COMMUNITY COUNCIL Minute of Meeting: Tuesday 28 March 2017 breakdown of the year to date expenditure of £516.99 and a forecast year end surplus of £757. -

Gourock Outdoor Pool & Fitness

Gourock Outdoor Pool Midnight Swims Triathlon A fresh crisp summer evening, clear sky and glistening stars The Inverclyde Leisure Triathlon has become one of the set the scene. The warmth of the pool, heated to 84 degrees country’s most attractive for multi event athletes. Over the Fahrenheit, creates the perfect atmosphere to marvel at the sprint distance, competitors will swim 800 metres, cycle 10 Gourock Outdoor delights of this unique swimming experience. miles, and finish with a 5 kilometre run all against the clock. Wednesday 1st July • Wednesday 15th July “This year’s event takes place on Sunday 23rd August 2015. Pool & Fitness Gym Wednesday 29th July • Wednesday 12th August Please enter online at www.entrycentral.com and search for “Inverclyde Leisure Sprint Distance Triathlon”. Admission is by ticket only which must be purchased in advance from reception. The Inverclyde free swim For more information, please contact us on 01475 715777. Albert Road, Gourock PA19 INQ arrangement does not apply to Midnight swims. Doors open at 9.45pm Pool Tel: 01475 715670 Classes @ Gourock Gym Welcome to Gourock Fitness Gym Gym Tel: 01475 715777 Class Times Inductions and person centred programmes with Body Blast: regular reviews are provided by our friendly staff to Mon/Wed/Fri: 9.30am ensure that your experience here will be enjoyable as Tues & Thurs: 6.00pm well as productive. Kettlebell Sessions Group Fitness classes are available for members Mon/Wed/Fri: and casual users at no extra cost and regular gym 10am & 5.30pm Tues & Thurs: challenges will help you measure improvements in 10.30am & 5.30pm performance. -

A Guide to Inverclyde's Beautiful Nature Walks

A guide to Inverclyde’s Beautiful Nature Walks Seán Batty Weather Forecaster GOUROCK From doing a lot of walking and cycling along the Clyde over the years for the STV Children’s Appeal, I’ve become more connected to our local surroundings and the nature within it. GREENOCK We have a beautiful landscape, which we’ve got to protect and preserve along with our wildflowers to allow our nature to thrive and flourish. A770 PORT GLASGOW 10 In my work as a meteorologist, I know the challenges presented by A78 A8 climate change and our sometimes volatile weather changes, particularly 1 7 to our pollinators such as bees. I’m keen to do my bit by including some bee-friendly plants in my own garden and learning more about the 2 3 A8 work of the Inverclyde Pollinator Corridor, who are planting up 4 patches of wild flowers across Inverclyde to help save pollinators. TO GLASGOW 6 This guide will help you to find some of the best easy family walks A761 9 in Inverclyde and the beautiful nature you might spot as you stroll. 5 LOCH INVERKIP THOM B788 INDEX OF WALKS 8 KILMACOLM OLD LARGS 1 Lunderston Bay ROAD 2 Inverclyde Coastal Trail WEMYSS BAY • B786 (National Route 753) COASTAL • QUARRIER’S VILLAGE 3 Ardgowan Estate 4 Finlaystone Country Estate • TO LARGS 5 Shielhill Glen Nature Trail FORESTS • 6 Leapmoor Forest & WOODS • 7 Greenock Cut HILLS, 8 Kelly Cut MOORS • 9 Glen Moss & BOGS • •10 Belville Biodiversity Garden Coastal Scenery & Wetland Wildlife: Clyde Estuary The Clyde Estuary stretches around the coastline of Inverclyde, 2 Inverclyde Coastal Trail (National from Port Glasgow as far as Wemyss Bay on the border of Route 753) which stretches south along this beautiful North Ayrshire, providing a large coastal wetland habitat coastline towards Inverkip Marina, bordering the mixed for wildlife, especially bird species.