Galapagos Tortoise. 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACTS 44Th Annual Meeting and Symposium Tucson, Arizona February 21–23, 2019

ABSTRACTS 44th Annual Meeting and Symposium Tucson, Arizona February 21–23, 2019 FORTY-FOURTH ANNUAL MEETING AND SYMPOSIUM THE DESERT TORTOISE COUNCIL TUCSON, AZ February 21–23, 2019 ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS AND POSTERS (Abstracts arranged alphabetically by last name of first author) *Speaker, if not the first author listed Long-term Data Collection and Trends of a 130-Acre High Desert Riparian and Upland Preserve in Northwestern Mohave County, Arizona Julie Alpert and Robert Faught Willow Creek Environmental Consulting, LLC, 15857 E. Silver Springs Road, Kingman, Arizona 86401, USA.Phone: 928-692-6501. Email: [email protected] The Willow Creek Riparian Preserve (Preserve) is a privately owned 130-acre site located 30 miles east of Kingman, Arizona. The Preserve was formally established in 2007 with the purchase of 10-acres and an agreement with the eastern adjoining private landowner to add an additional 120-acres. The Preserve location was unfenced and wholly accessible by livestock, off-road vehicle use, and hunting. In October of 2008 the Preserve was fenced with volunteer efforts from the local Rotary Club and Boy Scout Troop 66. Additional financial assistance came through a large discount in the cost of fencing materials from Kingman Ace Hardware. A total of 0.5-linear mile of new wildlife friendly fencing (barbless top wire and 18-inches above-ground bottom wire) was installed along the south and west sides and connected to existing Arizona State Lands cattle allotment fencing. Baseline and on-going studies and data collection have occurred since 2004. These have included small mammal live trapping; chiropteran surveys with the use of Anabat; migratory, breeding, and winter avian surveys; amphibian and reptile surveys; deployment of game cameras; animal track and sign identification and movement patterns; vegetation and plant surveys; and a wetland delineation. -

Sea Turtle Activity Book

Sea Turtle Adventures II The adventure continues... An Activity Book for All Ages Welcome to Sarasota County! The beautiful beaches and surrounding waters of Sarasota REMOVE OBSTACLES: Turtles can easily become trapped County provide critical habitat for important populations in beach furniture, recreational equipment, tents and of threatened and endangered sea turtles. We are honored toys, or fall into deep holes in the sand. You can provide that many sea turtles make Sarasota County their home a more natural and safe shoreline for the turtles to nest year-round, while other sea turtles migrate to our beaches by removing all items from the beach each night. Also, from hundreds of miles away to find mates and nest. remember to leave the beach as you found it by knocking down sandcastles, filling in holes, and picking up garbage, Each year between May 1 and Oct. 31, adult female sea especially plastics, which can be mistaken for food by turtles crawl out of the Gulf of Mexico to lay approximately sea turtles. 100 eggs in a sandy nest on our beaches. The clutch incubates for almost two months until the hatchlings We hope you enjoy learning more about sea turtles in this emerge one night and make their way to the Gulf. During activity book. Thank you for sharing the shore and helping this special time of year, there are many things you can do to make our beaches more turtle-friendly! to help and protect these magnificent animals. Sincerely, LIMIT LIGHTING: Lights on the beach confuse and disorient Your Friends at Sarasota County sea turtles. -

Loggerhead Sea Turtle

Loggerhead Sea Turtle Description: The Loggerhead Sea Turtle is named for its large head and blunt jaw. This huge sea turtle can grow to 800 pounds (though the average turtle is about 200 pounds) and three and a half feet in length. It is the largest hard-shelled turtle in the world. The carapace (shell) and flippers are reddish brown and the plastron (lower shell) is yellowish. The carapace has five lateral scutes and five central scutes. Scutes are hexagonal sections of the carapace. Underparts are white or whitish. These incredible turtles have powerful flippers that can propel them through the water at speeds of up to 16 miles per hour. The Loggerhead Sea Turtle has a life span of up to 50 years in the wild. Habitat/Range: The seafaring Loggerhead Sea Turtle is found throughout the world's tropical oceans. They are also found in temperate waters in search of food and in migration. Breeding populations exist in many locales including the Atlantic coast of the United States (from North Carolina to Florida), numerous Caribbean islands, Central America, the Mediterranean Sea, and Africa. Diet: Loggerhead Sea Turtles consume fish, crustaceans, mollusks, crabs, and jellyfish, They use their powerful jaws to crush prey. These turtles often ingest stray plastic bags which are mistaken for jellyfish and which cause potentially fatal complications. Nesting: The Female Loggerhead Sea Turtle normally lays her eggs on the same beach in which she was born. It may take up to 30 years before these turtles reach reproductive age. In June or July, females will emerge from the ocean and dig a hole in the sand. -

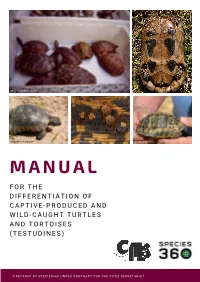

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

ECUADOR – Galapagos Giant Tortoises Stolen From

CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA NOTIFICATION TO THE PARTIES No. 2018/076 Geneva, 30 October 2018 CONCERNING: ECUADOR Galapagos giant tortoises stolen from breeding center 1. This Notification is being published at the request of Ecuador. 2. The CITES Management Authority of Ecuador informed the Secretariat that on 27 September 2018, the Galapagos National Park Directorate filed a criminal complaint in Ecuador following the theft of 123 live Galapagos giant tortoises (Chelonoidis niger) from the Galapagos National Park breeding center on Isabela Island. 3. The Galapagos giant tortoise (Chelonoidis niger1) is included in CITES Appendix I. 4. The stolen tortoises range from one to six years in age. One-year-old Galapagos giant tortoises may be around six centimetres in carapace length and weigh an estimated 200 grams. A six-year-old Galapagos giant tortoise could range from 12 to 30 centimetres in carapace length, and weigh around two kilograms. 5. The likely market for the stolen specimens is outside of Ecuador, and the CITES Management Authority of Ecuador therefore requests that the present Notification be distributed as widely as possible among police, customs and wildlife enforcement authorities. 6. Parties are requested to inform the CITES Management Authority of Ecuador should any permits or certificates regarding trade in these specimens be received. The Management Authority of Ecuador also requests that CITES Management Authorities do not approve any export, import or re-export permit applications related to this species before consulting with the CITES Management Authority of Ecuador. 7. Parties that seize illegally traded specimens of Chelonoidis niger are also requested to communicate information about these seizures to the Management Authority of Ecuador. -

TESTUDINIDAE Geochelone Chilensis

n REPTILIA: TESTUDINES: TESTUDINIDAE Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Ernst, C.H. 1998. Geochelone chilensis. Geochelone chilensis (Gray) Chaco Tortoise Testudo (Gopher) chilensis Gray 1870a: 190. Type locality, "Chili [Chile, South America]. " Restricted to Mendoza. Ar- gentina by Boulenger (1 889) without explanation (see Com- ments). Syntypes, Natural History Museum. London (BMNH), 1947.3.5.8-9, two stuffed juveniles; specimens missing as of August 1998 (fide C.J. McCarthy and C.H. Ernst, see Comments)(not examined by author). Testudo orgentinu Sclater 1870:47 1. See Comments. Testrrdo chilensis: Philippi 1872:68. Testrrrlo (Pamparestrrdo) chilensis: Lindholm 1929:285. Testucin (Chelonoidis) chilensis: Williams 1 950:22. Geochelone chilensis: Williams 1960: 10. First use of combina- tion. Geochelone (Che1onoide.r) chilensis: Auffenberg 197 1 : 1 10. Geochelone donosoharro.si Freiberg 1973533. Type locality, "San Antonio [Oeste], Rio Negro [Province, Argentina]." Ho- lotype, U.S. Natl. Mus. (USNM) 192961, adult male. col- lected by S. Narosky. 22 April 1971 (examined by author). Geochelone petersi Freibeg 197386. Type locality. "Kishka, La Banda. Santiago del Estero [Province, Argentina]." Ho- lotype, USNM 192959. subadult male, collected by J.J. Mar- n cos, 5 May 197 1 (examined by author). Geochelone ootersi: Freiberzm 1973:9 1. E-r errore. Geochelone (Chelonoidis) d1ilensi.s: Auffenberg 1974: 148. MAP. The circle marks the type locality; dots indicate other selected Geochelone ckilensis chilensis: Pritchard 1979:334. records: stars indicate fossil records. Geochelone ckilensis donosoburro.si: Pritchard 1979:335. Chelorroidis chilensis: Bour 1980:546. Geocheloni perersi: Freibeg 1984:30: growth annuli surround the slightly raised vertebral and pleural Chelorioidis donosoharrosi: Cei 1986: 148. -

Giant Tortoises with Pinta Island Ancestry Identified In

Biological Conservation 157 (2013) 225–228 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Short communication The genetic legacy of Lonesome George survives: Giant tortoises with Pinta Island ancestry identified in Galápagos a, a a,b c d Danielle L. Edwards ⇑, Edgar Benavides , Ryan C. Garrick , James P. Gibbs , Michael A. Russello , Kirstin B. Dion a, Chaz Hyseni a, Joseph P. Flanagan e, Washington Tapia f, Adalgisa Caccone a a Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA b Department of Biology, University of Mississippi, MS 38677, USA c College of Environmental Science and Forestry, State University of New York, Syracuse, NY 13210, USA d Department of Biology, University of British Columbia, Okanagan Campus, Kelowna, BC, Canada V1V 1V7 e Houston Zoo, Houston, TX 77030, USA f Galápagos National Park Service, Puerto Ayora, Galápagos, Ecuador article info abstract Article history: The death of Lonesome George, the last known purebred individual of Chelonoidis abingdoni native to Received 22 August 2012 Pinta Island, marked the extinction of one of 10 surviving giant tortoise species from the Galápagos Archi- Received in revised form 9 October 2012 pelago. Using a DNA reference dataset including historical C. abingdoni and >1600 living Volcano Wolf Accepted 14 October 2012 tortoise samples, a site on Isabela Island known to harbor hybrid tortoises, we discovered 17 individuals with ancestry in C. abingdoni. These animals belong to various hybrid categories, including possible first generation hybrids, and represent multiple, unrelated individuals. Their ages and relative abundance sug- Keywords: gest that additional hybrids and conceivably purebred C. -

Galapagos News

GALAPAGOS NEWS Fall-Winter 2015 NEW GIANT Flamingo Origins TORTOISE Disappearing SPECIES Opuntia Cacti NAMED! PROJECT UPDATES: Tortoises on Santa Fe Plans for Tortoises in 2016 Education for Sustainability PHOTOGRAPHING GALAPAGOS PHOTO CONTEST WINNERS! GALAPAGOS GIFTS ON SALE: GALAPAGOS CALENDAR 2016 www.galapagos.org Johannah Barry and a Galapagos National Park ranger, Freddy Villalva, watch feeding time for baby tortoises that reside at the Tortoise Center on Santa Cruz. © Ros Cameron, Galapagos Conservancy FROM THE PRESIDENT Johannah Barry CONTENTS nce again, we are delighted to share big news about big tortoises! With support from 3 GC Membership OGalapagos Conservancy, our colleagues at Yale University have embarked on an Galapagos Guardians ambitious program of genetic testing and identification of previously unidentified Galapagos 4-5 Galapagos News tortoises. That painstaking work was rewarded with the discovery of a new species of 6-7 The Mystery of the Galapagos tortoise — the Eastern Santa Cruz tortoise. Dr. Gisella Caccone, the study’s senior Disappearing Opuntia author, named the tortoise Chelonoidis donfaustoi after Fausto Llerena Sanchez, or "Don 8-9 In the Pink: Flamingos Fausto" as he is known by his friends. His 43-year history as a Galapagos National Park ranger 10-11 A Photographer's View also included a long relationship with Lonesome George as his primary keeper. This naming honors Don Fausto and celebrates the important work of the keepers and Park rangers whose from the Crater Rim work is indispensable to protecting and preserving Galapagos. 12-13 Galapagos Updates: We are pleased to highlight the work of long-time Galapagos scientists, Frank Sulloway Photo Contest, Desktop and Bob Tindle, whose seminal work on cactus ecology and flamingo population health have Wallpaper, SETECI, BBB spanned four decades. -

Scientists Try to Mate Galapagos Tortoise -- Again 21 January 2011

Scientists try to mate Galapagos tortoise -- again 21 January 2011 Scientists believe George may have a better chance of reproducing with his two new partners, of the Geochelone hoodensis species. The two potential mates arrived on Santa Cruz island, where George lives, on Thursday from the archipelago's Spanish Island. Genetic studies conducted by Yale University have shown that the newly arrived tortoises "are genetically closer ... more compatible, and could offer greater possibilities of producing offspring," In this July 21, 2008 file photo released by the the park's statement said. Galapagos National Park, a giant tortoise named "Lonesome George" is seen in the Galapagos islands, The Galapagos island chain, about 620 miles an archipelago off Ecuador's Pacific coast. Scientists are (1,000 kms) off Ecuador's coast, is home to unique still hoping to mate the elderly giant tortoise from the animal species that inspired Charles Darwin's ideas Galapagos - even though efforts over the past two on evolution. decades have failed. On Thursday, park officials said that they are providing two new female partners for George, who is believed to be the last living member of ©2010 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. the Geochelone abigdoni species. (AP Photo/ This material may not be published, broadcast, Galapagos National Park, File) rewritten or redistributed. Will Lonesome George ever become a dad? Scientists are still hoping to mate the near century- old giant tortoise from the Galapagos - even though efforts over the past two decades have failed. The Galapagos National Park said in a statement Thursday that they are providing two new female partners for George, who is believed to be the last living member of the Geochelone abigdoni species. -

Genetic Origins and Population Status of Desert Tortoises in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California: Initial Steps Towards Population Monitoring

G ENETIC ORIGINS AND POPULATION STATUS OF DESERT TORTOISES IN A NZA-BORREGO DESERT STATE PARK, CALIFORNIA: INITIAL STEPS TOWARDS POPULATION MONITORING Jeffrey A. Manning, Ph.D. Environmental Scientist California Department of Parks and Recreation Colorado Desert District 200 Palm Canyon Drive Borrego Springs, California 92004 November 2018 Manning, J.A. 2018. Genetic origins and population status of desert tortoises in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California: initial steps towards population monitoring. California Department of Parks and Recreation, Colorado Desert District, Borrego Springs, California. 89 pages. i Genetic Origins and Population Status of Desert Tortoises in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California: Initial Steps Towards Population Monitoring Final Report Jeffrey A. Manning, Ph.D., Author / Principle Investigator California Department of Parks and Recreation Colorado Desert District 200 Palm Canyon Drive Borrego Springs, California 92004 November 2018 Manning, J.A. 201 8. Genetic origins and population status of desert tortoises in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California: initial steps towards population monitoring. California Department of Parks and Recreation, Colorado Desert District, Borrego Springs, California. 89 pages. i FOREWORD The Desert tortoise (Gopherus sp.) was formally reported to science in 1861, and became the official California state reptile in 1972. Recent studies reveal three species, the Mojave desert tortoise (G. agassizii), Sonoran Desert tortoise (G. morafkai), and Sinaloan desert tortoise (G. evgoodei) (Murphy et al. 2011, Edwards et al. 2016; Figure 1). Range-wide declines in the Mojave desert tortoise population led California to prohibit the collection of this species in 1961. Despite this, it was emergency listed as federally endangered and state listed as threatened in 1989, and subsequently listed as federally threatened in 1990 (Federal Register 55, No 63, 50 CFR Part 17). -

Visual Cultures of De-Extinction and the Anthropocentric Archive Rosie Ibbotson University of Canterbury, New Zealand

Animal Studies Journal Volume 6 | Number 1 Article 6 2017 Making sense? Visual Cultures of De-extinction and the Anthropocentric Archive Rosie Ibbotson University of Canterbury, New Zealand Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj Part of the Art and Design Commons, Australian Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Education Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Philosophy Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ibbotson, Rosie, Making sense? Visual Cultures of De-extinction and the Anthropocentric Archive, Animal Studies Journal, 6(1), 2017, 80-103. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj/vol6/iss1/6 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Making sense? Visual Cultures of De-extinction and the Anthropocentric Archive Abstract This article examines the operations of visual representations within discourses advocating deextinction. Images have significant agency within these debates, yet their roles, and the assumptions they naturalise, have not been critiqued. Demonstrating the affective, triumphant and subversive potentials of these representations, this article then turns to the implications of relying on images made by and for humans within the expressly multispecies space of de-extinction. Discourses around de-extinction tend to place undue weight not just on how candidate species look(ed), but on how they appear to human eyes after the mediating processes of representation, and the notion of recreating a nonhuman animal that looks the same as an extinct species is not only limited as an aim of de-extinction technologies, but is problematised when different species’ modes of seeing and optical capacities are taken into account.