Status and Identification of Fox Sparrow Subspecies in the Central Valley of California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Alaska Birds & Wildlife

Alaska Birds & Wildlife Pribilof Islands - 25th to 27th May 2016 (4 days) Nome - 28th May to 2nd June 2016 (5 days) Barrow - 2nd to 4th June 2016 (3 days) Denali & Kenai Peninsula - 5th to 13th June 2016 (9 days) Scenic Alaska by Sid Padgaonkar Trip Leader(s): Forrest Rowland and Forrest Davis RBT Alaska – Trip Report 2016 2 Top Ten Birds of the Tour: 1. Smith’s Longspur 2. Spectacled Eider 3. Bluethroat 4. Gyrfalcon 5. White-tailed Ptarmigan 6. Snowy Owl 7. Ivory Gull 8. Bristle-thighed Curlew 9. Arctic Warbler 10. Red Phalarope It would be very difficult to accurately describe a tour around Alaska - without drowning the narrative in superlatives to the point of nuisance. Not only is it an inconceivably huge area to describe, but the habitats and landscapes, though far north and less biodiverse than the tropics, are completely unique from one portion of the tour to the next. Though I will do my best, I will fail to encapsulate what it’s like to, for example, watch a coastal glacier calving into the Pacific, while being observed by Harbour Seals and on-looking Murrelets. I can’t accurately describe the sense of wilderness felt looking across the vast glacial valleys and tundra mountains of Nome, with Long- tailed Jaegers hovering overhead, a Rock Ptarmigan incubating eggs near our feet, and Muskoxen staring at us strangers to these arctic expanses. Finally, there is Denali: squinting across jagged snowy ridges that tower above 10,000 feet, mere dwarfs beneath Denali standing 20,300 feet high, making everything else in view seem small, even toy-like, by comparison. -

Winter 2013 Volume 4, Issue 3 AZFO Elects New President

Arizona Field Ornithologists Arizona Field Ornithologists AZFO Studying Arizona Birds Winter 2013 Volume 4, Issue 3 AZFO ELECTS NEW PRESIDENT Visit us at By Doug Jenness http://azfo.org/ Kurt Radamaker has been elected to serve as the president of the AZFO for the next two years. He succeeds Troy Corman, who served in this capac- ity since the AZFO was founded eight years ago. Radamaker, a founding AZFO member, has served on the Board of Directors and developed the organi- zation’s website. He grew up in South- ern California where he started birding at the age of eight and by 15 had com- pleted Cornell Laboratory’s Seminars in Ornithology. He taught ornithology for four years at the University of La Verne, IN THIS ISSUE: a not-for-profit university near Los An- geles, and has led bird tours to several areas in the United States, Mexico, and Central with the presentation of an AZFO Achievement • AZFO New America. He has published numerous articles on Award. Although he is stepping down from cen- President birds, including in Arizona Birds Online, and is the tral executive responsibility, he plans to continue 1 author or a contributor to the following publica- to be active in the AZFO and to help out as need- tions: Arizona and New Mexico Birds (Lone Pine ed. Corman has worked for the Nongame Branch • Gale Monson Press, 2007); Species accounts for Bitterns, Her- of the Arizona Game and Fish Department since Grants ons and allies, and Ibises and Spoonbills in The 1990 and coordinated the Arizona Breeding Bird 1 Complete Guide to North American Birds (National Atlas project. -

NH Bird Records

V28 No4-Winter09-10_f 8/22/10 4:45 PM Page i New Hampshire Bird Records Winter 2009-10 Vol. 28, No. 4 V28 No4-Winter09-10_f 8/22/10 4:45 PM Page ii AUDUBON SOCIETY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE New Hampshire Bird Records Volume 28, Number 4 Winter 2009-10 Managing Editor: Rebecca Suomala 603-224-9909 X309, [email protected] Text Editor: Dan Hubbard Season Editors: Pamela Hunt, Spring; Tony Vazzano, Summer; Stephen Mirick, Fall; David Deifik, Winter Layout: Kathy McBride Assistants: Jeannine Ayer, Lynn Edwards, Margot Johnson, Susan MacLeod, Marie Nickerson, Carol Plato, William Taffe, Jean Tasker, Tony Vazzano Photo Quiz: David Donsker Photo Editor: Jon Woolf Web Master: Len Medlock Editorial Team: Phil Brown, Hank Chary, David Deifik, David Donsker, Dan Hubbard, Pam Hunt, Iain MacLeod, Len Medlock, Stephen Mirick, Robert Quinn, Rebecca Suomala, William Taffe, Lance Tanino, Tony Vazzano, Jon Woolf Cover Photo: Peregrine Falcon by Jon Woolf, 12/1/09, Hampton Beach State Park, Hampton, NH. New Hampshire Bird Records is published quarterly by New Hampshire Audubon’s Conservation Department. Bird sight- ings are submitted to NH eBird (www.ebird.org/nh) by many different observers. Records are selected for publication and not all species reported will appear in the issue. The published sightings typically represent the highlights of the season. All records are subject to review by the NH Rare Birds Committee and publication of reports here does not imply future acceptance by the Committee. Please contact the Managing Editor if you would like to report your sightings but are unable to use NH eBird. -

Birds on San Clemente Island, As Part of Our Work Toward the Recovery of the Island’S Endangered Species

WESTERN BIRDS Volume 36, Number 3, 2005 THE BIRDS OF SAN CLEMENTE ISLAND BRIAN L. SULLIVAN, PRBO Conservation Science, 4990 Shoreline Hwy., Stinson Beach, California 94970-9701 (current address: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 159 Sapsucker Woods Rd., Ithaca, New York 14850) ERIC L. KERSHNER, Institute for Wildlife Studies, 2515 Camino del Rio South, Suite 334, San Diego, California 92108 With contributing authors JONATHAN J. DUNN, ROBB S. A. KALER, SUELLEN LYNN, NICOLE M. MUNKWITZ, and JONATHAN H. PLISSNER ABSTRACT: From 1992 to 2004, we observed birds on San Clemente Island, as part of our work toward the recovery of the island’s endangered species. We increased the island’s bird list to 317 species, by recording many additional vagrants and seabirds. The list includes 20 regular extant breeding species, 6 species extirpated as breeders, 5 nonnative introduced species, and 9 sporadic or newly colonizing breeding species. For decades San Clemente Island had been ravaged by overgrazing, especially by goats, which were removed completely in 1993. Since then, the island’s vegetation has begun recovering, and the island’s avifauna will likely change again as a result. We document here the status of that avifauna during this transitional period of re- growth, between the island’s being largely denuded of vegetation and a more natural state. It is still too early to evaluate the effects of the vegetation’s still partial recovery on birds, but the beginnings of recovery may have enabled the recent colonization of small numbers of Grasshopper Sparrows and Lazuli Buntings. Sponsored by the U. S. Navy, efforts to restore the island’s endangered species continue—among birds these are the Loggerhead Shrike and Sage Sparrow. -

Cochise County Field Checklist

1 2 3 4 5 Note 1 2 3 4 5 Note Field Checklist of the Birds of Field Checklist of Cochise County The Birds of Cochise County Checklist of the Birds of Cochise County This list conforms to the A.O.U. checklist order and nomenclature, as of July 2005. * = Arizona bird committee review species. #= Arizona bird committee sketch details (int) Introduced Checklists available at Arizona Field Ornithologists Website http://AZFO.org Regional Reports Coordinator Mark Stevenson layout and design by Kurt and Cindy Radamaker October 2005 1 2 3 4 5 Note Great-tailed Grackle ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Bronzed Cowbird ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Locality __________________________________ Brown-headed Cowbird ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Observer(s) _______________________________ Orchard Oriole* ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 1 Date __________Time ______ Total Species ____ Hooded Oriole ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Streak-backed Oriole* Weather __________________________________ ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Baltimore Oriole* Remarks __________________________________ ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Bullock’s Oriole ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Scott’s Oriole ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Fringillidae - Finches and Goldfinches ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Pine Grosbeak Locality __________________________________ ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Purple Finch* ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Observer(s) _______________________________ Cassin’s Finch ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 2 Date __________Time ______ Total Species ____ House Finch ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Weather __________________________________ Red Crossbill ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Pine Siskin Remarks __________________________________ -

Demography of Sooty Fox Sparrows Following a Shift from a Migratory to Resident Life History

Canadian Journal of Zoology Demography of sooty fox sparrows following a shift from a migratory to resident life history Journal: Canadian Journal of Zoology Manuscript ID cjz-2017-0102.R2 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the Author: 08-Oct-2017 Complete List of Authors: Visty, Hannah; University of British Columbia, Forest and Conservation Sciences Wilson, Scott; Environment and Climate Change Canada, National Wildlife Research CentreDraft Germain, Ryan; University of British Columbia, Forest and Conservation Science; University of Aberdeen, Institute of Biological and Environmental Sciences Krippel, Jessica; University of British Columbia, Forest and Conservation Science Arcese, Peter; Univ of British Columba, sooty fox sparrow, demography, population growth, MIGRATION < Keyword: Discipline, colonization, Passerella unalaschcensis https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/cjz-pubs Page 1 of 20 Canadian Journal of Zoology 1 Demography of sooty fox sparrows following a shift from a migratory to resident life history Hannah Visty1, Scott Wilson2, Ryan Germain1,3, Jessica Krippel1, and Peter Arcese1 1Department of Forest and Conservation Sciences, 2424 Main Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 2Environment and Climate Change Canada, National Wildlife Research Centre, 1125 Colonel by Drive, Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3; [email protected] 3Institute of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Zoology Building, University of Aberdeen, Tillydrone Avenue, Aberdeen, AB24 2TZ, United Kingdom; [email protected] Draft Contact author: Hannah Visty, Department of Forest and Conservation Sciences, 2424 Main Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4; [email protected]; Phone: 778-985-6200; Fax: 8229103 https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/cjz-pubs Canadian Journal of Zoology Page 2 of 20 2 Demography of sooty fox sparrows following a shift from a migratory to resident life history Hannah Visty (H. -

Songbird Remix Sparrows of the World

Avian Models for 3D Applications Characters and Texture Mapping by Ken Gilliland 1 Songbird ReMix Sparrows of the World Contents Manual Introduction 3 Overview and Use 3 Creating a Songbird ReMix Bird with Poser or DAZ Studio 4 One Folder to Rule Them All 4 Physical-based Rendering 5 Posing & Shaping Considerations 5 Where to Find Your Birds and Poses 6 Field Guide List of Species 7 Old World Sparrows Spanish Sparrow 8 Italian Sparrow 10 Eurasian Tree Sparrow 12 Dead Sea Sparrow 14 Arabian Golden Sparrow 16 Russet Sparrow 17 Cape Sparrow 19 Great Sparrow 21 Chestnut Sparrow 23 New World Sparrows American Tree Sparrow 25 Harris's Sparrow 28 Fox Sparrow 30 Golden-crowned Sparrow 32 Lark Sparrow 35 Lincoln's Sparrow 37 Rufous-crowned Sparrow 39 Savannah Sparrow 43 Rufous-winged Sparrow 47 Resources, Credits and Thanks 49 Copyrighted 2013-20 by Ken Gilliland www.songbirdremix.com Opinions expressed on this booklet are solely that of the author, Ken Gilliland, and may or may not reflect the opinions of the publisher. 2 Songbird ReMix Sparrows of the World Introduction Sparrows are probably the most familiar of all wild birds. Throughout history sparrows have been considered the harbinger of good or bad luck. They are referred to in many works of ancient literature and religious texts around the world. The ancient Egyptians used the sparrow symbol in their hieroglyphs to express evil tidings, the ancient Greeks associated it with Aphrodite, the goddess of love as a lustful messenger, and Jesus used sparrows as an example of divine providence in the Gospel of Matthew. -

Determining Breeding Areas and Migration Routes of Coastal

Determining Breeding Areas and Migration Routes of Coastal Northwest Sooty Fox Sparrows (Passerella iliaca unalaschcensis ) Over-Wintering on Vancouver Island using Geolocators Summary The phylogeography of the Fox Sparrow ( Passerella iliaca ) has been much debated, but birds breeding along the west coast of North America are generally considered to be a separate species ( Passerella iliaca unalaschecensis ) based on mitochondrial DNA. Using plumage characteristics, a further seven sub- species have been identified within this group. These subspecies, and their migration patterns, have become an emblematic example of leap-frog migration, based upon the early work of Swarth (1920). However, more recently, these connectivity patterns have been called into question, partly based on the relative difficulty in accurately distinguishing plumages and subspecies in the field. Light-level geolcators are now small enough to be carried by <50 g songbirds and can reveal remarkable new insights into migration patterns and behaviour. Using geolocators, we will track a population of Fox Sparrows overwintering on southern Vancouver Island to their breeding areas. The objectives of this study are two-fold: 1) Based on leapfrog patterns identified by Swarth (1920) we will use direct-tracking methods to test the hypothesis that birds overwintering on Vancouver Island breed on the island and do not mix with birds along the northwest coast (i.e. strong connectivity) and 2) Identify connections between overwintering and breeding areas that are important to conservation and management of Fox Sparrow populations. Personnel • Project Leader: Michael Simmons, Rocky Point Bird Observatory (RPBO) • Migration Research Advisor: Dr. Bridget Stutchbury, York University • Science and Geolocator Technical Advisor and Data Analyst: Dr. -

Fourteenth Supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-List of North American Birds

"^"iqS^'^] Fourteenth SuppkmeiU to the A. 0. U. Check-List. 343 FOURTEENTH SUPPLEMENT TO THE AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION CHECK-LIST OF NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS. The Thirteenth Supplement to the Check-List was issued in July, 1904 (Auk, XXI, pp. 41 1-424). ^ Since this date the Com- mittee has held six sessions, all except one in Washington, at the following dates : April 21-25, 1905; January 17-20, 1906; Novem- ber 16-17, 1906; April 18-23, 1907; December 12, 1907 (at Phila- delphia); April 15-20, 1908. In view of the probable early appearance of a third edition of the Check-List, authorized by the Union at the Stated ^Meeting held in November, 1906, it seemed best to the Committee to withhold its reports from publication till the results of its work should appear in the new Check-List. Now that the manuscript for the new edition is practically completed, it seems desirable that the Com- mittee should, in accordance with precedent, give reasons for the changes it has instituted during the last four years, since these cannot be readily indicated in the Check-List. Its decisions involve, as usual, additions to and eliminations from the Check- List, changes in nomenclature and in the status of groups, and the rejection of many proposed additions, and changes in nomenclature and status. The Committee has aimed to secure as stable a foundation, as possible for the new Check-List, anticipating a few changes in names that would soon surely arise, as well as those already pro- posed. Nearly all of the nomenclature changes here recorded are due to the strict enforcement of the laAv of priority, and result from the recent bibliographic work of a large number of investi- gators, abroad as well as in America. -

Migration of Birds Circular 16

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Migration of Birds Circular 16 Migration of Birds Circular 16 by Frederick C. Lincoln, 1935 revised by Steven R. Peterson, 1979 revised by John L. Zimmerman, 1998 Division of Biology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS Associate editor Peter A. Anatasi Illustrated by Bob Hines U.S. FISH & WILDLIFE SERVICE D E R P O A I R R E T T M N EN I T OF THE U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE..............................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................2 EARLY IDEAS ABOUT MIGRATION............................................................4 TECHNIQUES FOR STUDYING MIGRATION..........................................6 Direct Observation ....................................................................................6 Aural ............................................................................................................7 Preserved Specimens ................................................................................7 Marking ......................................................................................................7 Radio Tracking ..........................................................................................8 Radar Observation ....................................................................................9 EVOLUTION OF MIGRATION......................................................................10 -

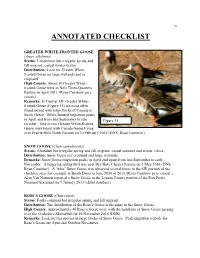

2016 Annotated Checklist of Birds on the Fort

16 ANNOTATED CHECKLIST GREATER WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE (Anser albifrons) Status: Uncommon but irregular spring and fall migrant, casual winter visitor. Distribution: Look for Greater White- fronted Geese on large wetlands and in cropland. High Counts: About 10 Greater White- fronted Geese were in Nels Three-Quarters Pasture in April 2011 (Ryan Cumbow pers. comm.). Remarks: In Central SD, Greater White- fronted Geese (Figure 15) are most often found mixed with large flocks of Canada or Snow Geese. White-fronted migration peaks in April and from late September to late Figure 15. October. One or two Greater White-fronted Geese were heard with Canada Geese flying over Prairie Hills North Pasture on 10 February 2015 (DNS, Ryan Cumbow). SNOW GOOSE (Chen caerulescens) Status: Abundant but irregular spring and fall migrant, casual summer and winter visitor. Distribution: Snow Geese use cropland and large wetlands. Remarks: Snow Goose migration peaks in April and again from late September to early November. A lingering spring bird was near Dry Hole Chester Pasture on 1 May 2014 (DNS, Ryan Cumbow). A “blue” Snow Goose was observed several times in the SW portion of the checklist area (for example at Booth Dam) in June 2010 or 2011 (Ryan Cumbow pers. comm.). Alan Van Norman reported a Snow Goose in the Lyman County portion of the Fort Pierre National Grassland on 5 January 2013 (eBird database). ROSS’S GOOSE (Chen rossii) Status: Fairly common but irregular spring and fall migrant. Distribution: The distribution of the Ross’s Goose is the same as the Snow Goose. High Counts: Approximately 40 Ross’s Geese were with the hundreds of Snow Geese passing over the Cookstove Shelterbelt on 10 November 2014 (DNS).