Web of Science and Scopus Are Not the Only Options SHORT COMMUNICATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citation Analysis for the Modern Instructor: an Integrated Review of Emerging Research

CITATION ANALYSIS FOR THE MODERN INSTRUCTOR: AN INTEGRATED REVIEW OF EMERGING RESEARCH Chris Piotrowski University of West Florida USA Abstract While online instructors may be versed in conducting e-Research (Hung, 2012; Thelwall, 2009), today’s faculty are probably less familiarized with the rapidly advancing fields of bibliometrics and informetrics. One key feature of research in these areas is Citation Analysis, a rather intricate operational feature available in modern indexes such as Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, and PsycINFO. This paper reviews the recent extant research on bibliometrics within the context of citation analysis. Particular focus is on empirical studies, review essays, and critical commentaries on citation-based metrics across interdisciplinary academic areas. Research that relates to the interface between citation analysis and applications in higher education is discussed. Some of the attributes and limitations of citation operations of contemporary databases that offer citation searching or cited reference data are presented. This review concludes that: a) citation-based results can vary largely and contingent on academic discipline or specialty area, b) databases, that offer citation options, rely on idiosyncratic methods, coverage, and transparency of functions, c) despite initial concerns, research from open access journals is being cited in traditional periodicals, and d) the field of bibliometrics is rather perplex with regard to functionality and research is advancing at an exponential pace. Based on these findings, online instructors would be well served to stay abreast of developments in the field. Keywords: Bibliometrics, informetrics, citation analysis, information technology, Open resource and electronic journals INTRODUCTION In an ever increasing manner, the educational field is irreparably linked to advances in information technology (Plomp, 2013). -

1 Data Policies of Highly-Ranked Social Science

1 Data policies of highly-ranked social science journals1 Mercè Crosas2, Julian Gautier2, Sebastian Karcher3, Dessi Kirilova3, Gerard Otalora2, Abigail Schwartz2 Abstract By encouraging and requiring that authors share their data in order to publish articles, scholarly journals have become an important actor in the movement to improve the openness of data and the reproducibility of research. But how many social science journals encourage or mandate that authors share the data supporting their research findings? How does the share of journal data policies vary by discipline? What influences these journals’ decisions to adopt such policies and instructions? And what do those policies and instructions look like? We discuss the results of our analysis of the instructions and policies of 291 highly-ranked journals publishing social science research, where we studied the contents of journal data policies and instructions across 14 variables, such as when and how authors are asked to share their data, and what role journal ranking and age play in the existence and quality of data policies and instructions. We also compare our results to the results of other studies that have analyzed the policies of social science journals, although differences in the journals chosen and how each study defines what constitutes a data policy limit this comparison. We conclude that a little more than half of the journals in our study have data policies. A greater share of the economics journals have data policies and mandate sharing, followed by political science/international relations and psychology journals. Finally, we use our findings to make several recommendations: Policies should include the terms “data,” “dataset” or more specific terms that make it clear what to make available; policies should include the benefits of data sharing; journals, publishers, and associations need to collaborate more to clarify data policies; and policies should explicitly ask for qualitative data. -

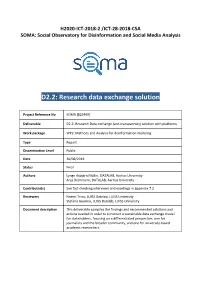

D2.2: Research Data Exchange Solution

H2020-ICT-2018-2 /ICT-28-2018-CSA SOMA: Social Observatory for Disinformation and Social Media Analysis D2.2: Research data exchange solution Project Reference No SOMA [825469] Deliverable D2.2: Research Data exchange (and transparency) solution with platforms Work package WP2: Methods and Analysis for disinformation modeling Type Report Dissemination Level Public Date 30/08/2019 Status Final Authors Lynge Asbjørn Møller, DATALAB, Aarhus University Anja Bechmann, DATALAB, Aarhus University Contributor(s) See fact-checking interviews and meetings in appendix 7.2 Reviewers Noemi Trino, LUISS Datalab, LUISS University Stefano Guarino, LUISS Datalab, LUISS University Document description This deliverable compiles the findings and recommended solutions and actions needed in order to construct a sustainable data exchange model for stakeholders, focusing on a differentiated perspective, one for journalists and the broader community, and one for university-based academic researchers. SOMA-825469 D2.2: Research data exchange solution Document Revision History Version Date Modifications Introduced Modification Reason Modified by v0.1 28/08/2019 Consolidation of first DATALAB, Aarhus draft University v0.2 29/08/2019 Review LUISS Datalab, LUISS University v0.3 30/08/2019 Proofread DATALAB, Aarhus University v1.0 30/08/2019 Final version DATALAB, Aarhus University 30/08/2019 Page | 1 SOMA-825469 D2.2: Research data exchange solution Executive Summary This report provides an evaluation of current solutions for data transparency and exchange with social media platforms, an account of the historic obstacles and developments within the subject and a prioritized list of future scenarios and solutions for data access with social media platforms. The evaluation of current solutions and the historic accounts are based primarily on a systematic review of academic literature on the subject, expanded by an account on the most recent developments and solutions. -

A Comprehensive Analysis of the Journal Evaluation System in China

A comprehensive analysis of the journal evaluation system in China Ying HUANG1,2, Ruinan LI1, Lin ZHANG1,2,*, Gunnar SIVERTSEN3 1School of Information Management, Wuhan University, China 2Centre for R&D Monitoring (ECOOM) and Department of MSI, KU Leuven, Belgium 3Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education, Tøyen, Oslo, Norway Abstract Journal evaluation systems are important in science because they focus on the quality of how new results are critically reviewed and published. They are also important because the prestige and scientific impact of journals is given attention in research assessment and in career and funding systems. Journal evaluation has become increasingly important in China with the expansion of the country’s research and innovation system and its rise as a major contributor to global science. In this paper, we first describe the history and background for journal evaluation in China. Then, we systematically introduce and compare the most influential journal lists and indexing services in China. These are: the Chinese Science Citation Database (CSCD); the journal partition table (JPT); the AMI Comprehensive Evaluation Report (AMI); the Chinese STM Citation Report (CJCR); the “A Guide to the Core Journals of China” (GCJC); the Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI); and the World Academic Journal Clout Index (WAJCI). Some other lists published by government agencies, professional associations, and universities are briefly introduced as well. Thereby, the tradition and landscape of the journal evaluation system in China is comprehensively covered. Methods and practices are closely described and sometimes compared to how other countries assess and rank journals. Keywords: scientific journal; journal evaluation; peer review; bibliometrics 1 1. -

Downloaded Manually1

The Journal Coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: a Comparative Analysis Philippe Mongeon and Adèle Paul-Hus [email protected]; [email protected] Université de Montréal, École de bibliothéconomie et des sciences de l'information, C.P. 6128, Succ. Centre-Ville, H3C 3J7 Montréal, Qc, Canada Abstract Bibliometric methods are used in multiple fields for a variety of purposes, namely for research evaluation. Most bibliometric analyses have in common their data sources: Thomson Reuters’ Web of Science (WoS) and Elsevier’s Scopus. This research compares the journal coverage of both databases in terms of fields, countries and languages, using Ulrich’s extensive periodical directory as a base for comparison. Results indicate that the use of either WoS or Scopus for research evaluation may introduce biases that favor Natural Sciences and Engineering as well as Biomedical Research to the detriment of Social Sciences and Arts and Humanities. Similarly, English-language journals are overrepresented to the detriment of other languages. While both databases share these biases, their coverage differs substantially. As a consequence, the results of bibliometric analyses may vary depending on the database used. Keywords Bibliometrics, citations indexes, Scopus, Web of Science, research evaluation Introduction Bibliometric and scientometric methods have multiple and varied application realms, that goes from information science, sociology and history of science to research evaluation and scientific policy (Gingras, 2014). Large scale bibliometric research was made possible by the creation and development of the Science Citation Index (SCI) in 1963, which is now part of Web of Science (WoS) alongside two other indexes: the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) and the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI) (Wouters, 2006). -

A Bibliometric Visualization of the Economics and Sociology of Wealth Inequality: a World Apart?

Scientometrics (2019) 118:849–868 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-03000-z A bibliometric visualization of the economics and sociology of wealth inequality: a world apart? Philipp Korom1 Received: 20 April 2018 / Published online: 24 January 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Wealth inequality research is fragmented across diferent social science disciplines. This article explores the potential of interdisciplinary perspectives by investigating the thematic overlap between economic and sociological approaches to wealth inequality. To do so, we use the Web of Science citation database to identify pertinent articles on the topic of wealth inequality in each discipline (1990‒2017). On the basis of complete bibliographies of these selected articles, we construct co-citation networks and obtain thematic clusters. What becomes evident is a low thematic overlap: Economists explore the causes of wealth ine- quality based on mathematical models and study the interplay between inequality and eco- nomic growth. Sociologists focus mostly on wealth disparities between ethnic groups. The article identifes, however, a few instances of cross-disciplinary borrowing and the French economist Thomas Piketty as a novel advocate of interdisciplinarity in the feld. The pros- pects of an economics-cum-sociology of wealth inequality are discussed in the conclusion. Keywords Wealth inequality · Interdisciplinarity · Co-citation networks · VOSviewer · Piketty Rising disparities in ownership of private assets in the past few decades have become a matter of general concern that increasingly commands the attention of diferent disci- plines: Historians, for example, chronicle the evolution of wealth inequality from the dawn of mankind to modernity (Scheidel 2017); social geographers map the locational habits and trajectories of the super-rich (Forrest et al. -

Why Are New Journals Created?

Why are new journals created? An international analysis of Information and Documentation titles (2013-2018) Cristóbal Urbano; Rosângela Schwarz Rodrigues; Marta Somoza-Fernández; Josep- Manuel Rodríguez-Gairín Nota: Este artículo se puede leer en español en: http://www.elprofesionaldelainformacion.com/contenidos/2020/jul/urbano-rodrigues-somoza-rodriguez_es.pdf How to cite this article: Urbano, Cristóbal; Rodrigues, Rosângela Schwarz; Somoza-Fernández, Marta; Rodríguez-Gairín, Josep-Ma- nuel (2020). “Why are new journals created? An international analysis of Information and Documentation titles (2013-2018)”. Profesional de la información, v. 29, n. 4, e290413. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.jul.13 Manuscript received on April 28th 2020 Accepted on June 08th 2020 Cristóbal Urbano * Rosângela Schwarz Rodrigues https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0935-6436 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9639-6390 Universitat de Barcelona, Departament Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, de Biblioteconomia, Documentació i Programa de Pós-Graduação en Ciência da Comunicació Audiovisual Informação. Melcior de Palau, 140 Florianópolis, SC, Brazil. 08014 Barcelona, Spain [email protected] [email protected] Marta Somoza-Fernández Josep-Manuel Rodríguez-Gairín https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4769-9010 https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8375-7911 Universitat de Barcelona, Departament Universitat de Barcelona, Departament de Biblioteconomia, Documentació i de Biblioteconomia, Documentació i Comunicació Audiovisual Comunicació Audiovisual Melcior de Palau, 140 Melcior de Palau, -

POETICS Journal of Empirical Research on Culture, the Media and the Arts

POETICS Journal of Empirical Research on Culture, the Media and the Arts AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Audience p.2 • Impact Factor p.2 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 0304-422X DESCRIPTION . Poetics is an interdisciplinary journal of theoretical and empirical research on culture, the media and the arts. Particularly welcome are papers that make an original contribution to the major disciplines - sociology, psychology, media and communication studies, and economics - within which promising lines of research on culture, media and the arts have been developed. Poetics would be pleased to consider, for example, the following types of papers: • Sociological research on participation in the arts; media use and consumption; the conditions under which makers of cultural products operate; the functioning of institutions that make, distribute and/ or judge cultural products, arts and media policy; etc. • Psychological research on the cognitive processing of cultural products such as literary texts, films, theatrical performances, visual artworks; etc. • Media and communications research on the globalization of media production and consumption; the role and performance of journalism; the development of media and creative industries; the social uses of media; etc. • Economic research on the funding, costs and benefits of commercial and non-profit organizations in the fields of art and culture; choice behavior of audiences analysed from the viewpoint of the theory of lifestyles; the impact of economic institutions on the production or consumption of cultural goods; etc. The production and consumption of media, art and culture are highly complex and interrelated phenomena. -

Ohiolink Librarians and Google Scholar Over Time: a Longitudinal Analysis of Attitudes and Uses

University of Dayton eCommons Roesch Library Faculty Publications Roesch Library 8-20-2020 OhioLINK Librarians and Google Scholar Over Time: A Longitudinal Analysis of Attitudes and Uses David Luftig Washington State University Joan Plungis University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/roesch_fac Part of the Scholarly Communication Commons eCommons Citation David Luftig and Joan Plungis (2020). OhioLINK Librarians and Google Scholar Over Time: A Longitudinal Analysis of Attitudes and Uses. Reference Services Review. , https://ecommons.udayton.edu/roesch_fac/67 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Roesch Library at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Roesch Library Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Page 1 of 34 Reference Services Review 1 2 3 4 5 6 OhioLINK Librarians and Google Scholar Over Time: A Longitudinal 7 8 9 Analysis of Attitudes and Uses 10 11 This study provides a longitudinal analysis of the opinions and uses of Google Scholar 12 Reference Services Review 13 by members of the OhioLINK consortium of libraries. Using survey data collected in 2007, 14 15 2014, and 2019 via the OhioLINK Listserv, this study explores how librarians use and 16 17 18 promote Google Scholar within their library instruction sessions and how Google Scholar 19 20 and its Library Links feature are promoted on library websites. This information is then 21 22 analyzed across the three date ranges. The results of this research suggested that there 23 24 were significant changes in the use and opinions of Google Scholar between 2007 and 25 26 2014 with more normalization of uses and opinions occurring between 2014 and 2019. -

Journal of Informetrics

JOURNAL OF INFORMETRICS AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Impact Factor p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.1 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.3 ISSN: 1751-1577 DESCRIPTION . Journal of Informetrics (JOI) publishes rigorous high-quality research on quantitative aspects of information science. The main focus of the journal is on topics in bibliometrics, scientometrics, webometrics, patentometrics, altmetrics and research evaluation. Contributions studying informetric problems using methods from other quantitative fields, such as mathematics, statistics, computer science, economics and econometrics, and network science, are especially encouraged. JOI publishes both theoretical and empirical work. In general, case studies, for instance a bibliometric analysis focusing on a specific research field or a specific country, are not considered suitable for publication in JOI, unless they contain innovative methodological elements. IMPACT FACTOR . 2020: 5.107 © Clarivate Analytics Journal Citation Reports 2021 ABSTRACTING AND INDEXING . CSA Database LISA (Library and Information Science Abstracts) EBSCOhost Current Abstracts Scopus PubMed/Medline PubMed/Medline Current Contents Social Sciences Citation Index Web of Science Computers & Applied Sciences Complete TOC Premier INSPEC AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK 28 Sep 2021 www.elsevier.com/locate/joi 1 EDITORIAL BOARD . Editor-in-Chief Mu-Hsuan Huang, National Taiwan University Department of Library and Information Science, No. 1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Road, 10617, Taipei, Taiwan Founding Editor Leo Egghe, Hasselt University, Belgium Associate Editor Jiang Li, Nanjing University School of Information Management, China Editorial Board Members Peter van den Besselaar, VU Amsterdam, Netherlands Dar-Zen Chen, National Taiwan University, Department of Mechanical Engineering and Institute of Industrial Engineering, Taiwan Juan Gorraiz, University of Vienna, Austria Robin Haunschild, Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research, Germany Hamid R. -

What Happens When a Journal Converts to Open Access? a Bibliometric Analysis

What happens when a journal converts to Open Access? A bibliometric analysis Fakhri Momeni1*, Philipp Mayr1,2*, Nicholas Fraser 3* and Isabella Peters4 1 [email protected] GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, Unter Sachsenhausen 6-8, 50667 Cologne (Germany) [email protected] Institute of Computer Science, University of Göttingen, (Germany) 3 [email protected], [email protected] ZBW – Leibniz Information Centre for Economics, Düsternbrooker Weg 120, 24105 Kiel (Germany) * Correspondence: [email protected], [email protected] and [email protected] Abstract In recent years, increased stakeholder pressure to transition research to Open Access has led to many journals converting, or ‘flipping’, from a closed access (CA) to an open access (OA) publishing model. Changing the publishing model can influence the decision of authors to submit their papers to a journal, and increased article accessibility may influence citation behaviour. In this paper we aimed to understand how flipping a journal to an OA model influences the journal’s future publication volumes and citation impact. We analysed two independent sets of journals that had flipped to an OA model, one from the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) and one from the Open Access Directory (OAD), and compared their development with two respective control groups of similar journals. For bibliometric analyses, journals were matched to the Scopus database. We assessed changes in the number of articles published over time, as well as two citation metrics at the journal and article level: the normalised impact factor (IF) and the average relative citations (ARC), respectively. -

Social Science & Medicine

SOCIAL SCIENCE & MEDICINE AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Audience p.2 • Impact Factor p.2 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.6 ISSN: 0277-9536 DESCRIPTION . Social Science & Medicine provides an international and interdisciplinary forum for the dissemination of social science research on health. We publish original research articles (both empirical and theoretical), reviews, position papers and commentaries on health issues, to inform current research, policy and practice in all areas of common interest to social scientists, health practitioners, and policy makers. The journal publishes material relevant to any aspect of health from a wide range of social science disciplines (anthropology, economics, epidemiology, geography, policy, psychology, and sociology), and material relevant to the social sciences from any of the professions concerned with physical and mental health, health care, clinical practice, and health policy and organization. We encourage material which is of general interest to an international readership. The journal publishes the following types of contribution: 1) Peer-reviewed original research articles and critical analytical reviews in any area of social science research relevant to health and healthcare. These papers may be up to 9000 words including abstract, tables, figures, references and (printed) appendices as well as the main text. Papers below this limit are preferred. 2) Systematic reviews and literature reviews of up to 15000 words including abstract, tables, figures, references and (printed) appendices as well as the main text. 3) Peer-reviewed short communications of findings on topical issues or published articles of between 2000 and 4000 words.