LSE IDEAS Geopolitics of Eurasian Economic Intergration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preventing Deglobalization: an Economic and Security Argument for Free Trade and Investment in ICT Sponsors

Preventing Deglobalization: An Economic and Security Argument for Free Trade and Investment in ICT Sponsors U.S. CHAMBER OF COMMERCE FOUNDATION U.S. CHAMBER OF COMMERCE CENTER FOR ADVANCED TECHNOLOGY & INNOVATION Contributing Authors The U.S. Chamber of Commerce is the world’s largest business federation representing the interests of more than 3 million businesses of all sizes, sectors, and regions, as well as state and local chambers and industry associations. Copyright © 2016 by the United States Chamber of Commerce. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form—print, electronic, or otherwise—without the express written permission of the publisher. Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 6 Part I: Risks of Balkanizing the ICT Industry Through Law and Regulation ........................................................................................ 11 A. Introduction ................................................................................................. 11 B. China ........................................................................................................... 14 1. Chinese Industrial Policy and the ICT Sector .................................. 14 a) “Informatizing” China’s Economy and Society: Early Efforts ...... 15 b) Bolstering Domestic ICT Capabilities in the 12th Five-Year Period and Beyond ................................................. 16 (1) 12th Five-Year -

Selecting Import Products and Suppliers 409

Chapter 17 SelectingSelecting Import Import Products andProducts Suppliers and Suppliers TYPES OF PRODUCTS FOR IMPORTATION One of the most important import decisions is the selection of the proper product that serves the market need. In the absence of the latter, one is left with a warehouse full of merchandise with no one interested in buying it. Nevertheless, importing can become a successful and profitable venture so long as sufficient effort and time is invested in selecting the right product for the target market. How does one find the right product to import? The following are differ- ent types of products to consider. Unique Products Products that are unique and different can be appealing to customers be- cause they are a welcome change from the standardized and identical prod- ucts sold in the domestic market. The fact that a product is imported and different is in itself sufficient for many people to purchase the item. However, some studies indicate product uniqueness in terms of cultural appeal to be a relatively less important variable in the purchasing decision of import man- agers (Ghymn, 1983). Less Expensive Products It is quite common to find imports that perform identically to the competi- tor’s product but can be sold at a much lower price. As customers quickly switch allegiance to buy the imported item, it is quite possible to capture a substantial share of the domestic market. Export-Import Theory, Practices, and Procedures, Second Edition 407 408 EXPORT-IMPORT THEORY, PRACTICES, AND PROCEDURES For firms selling in mature markets where there is little or no product dif- ferentiation, cost reduction provides a competitive advantage (Shippen, 1999). -

The Outsourcing Handbook a Guide to Outsourcing

The Outsourcing Handbook A guide to outsourcing Version 2.0 To start a new section, hold down the apple+shift keys and click to release this object and type the section title in the box below. Contents Introduction 4 Provides a brief overview of what outsourcing is, and describes Deloitte’s approaches to Outsourcing Advisory Services (OAS). 1 Phase 1 – Assess 10 The first phase of the process where requirements are defined and which vendors to engage with are reviewed. 2 Phase 2 – Prepare 16 The second phase of the process where initial vendor selection is undertaken and an RFP produced. 3 Phase 3 – Evaluate 22 The third phase of the process where vendor proposals are evaluated and a short-list of vendors for commercial negotiation is selected. 4 Phase 4 – Commit 30 The fourth phase of the process where contracts are negotiated and a deal agreed. 5 Phase 5 – Transition and Transform 38 The fifth phase of the process where the work and resources are transitioned to the successful vendor. 6 Phase 6 – Optimise 44 The final phase of the process covering the steady-state management of the outsourcing arrangement. To start a new section, hold down the apple+shift keys and click to release this object and type the section title in the box below. Foreword Love it or loathe it, outsourcing is now a permanent feature of business life. As companies search for cheaper and more effective ways of working, handing over non-core functions to lower cost specialists can be an alluring prospect. But before you bring in third parties to run parts of your business, it is worth pausing to consider the risks. -

Service Offshoring and Productivity

Service Offshoring and Productivity: Evidence from the US∗ Mary Amiti Federal Reserve Bank of New York and CEPR Shang-Jin Wei International Monetary Fund, CEPR and NBER Abstract The practice of sourcing service inputs from overseas suppliers has been growing in response to new technologies that have made it possible to trade in some business and computing services that were previously considered non-tradable. This paper estimates the effects of offshoring on productivity in US manufacturing industries between 1992 and 2000. It finds that service offshoring has a significant positive effect on productivity in the US, accounting for around 10 percent of labor productivity growth during this period. Offshoring material inputs also has a positive effect on productivity, but the magnitude is smaller accounting for approximately 5 percent of productivity growth. Keywords: offshoring, outsourcing, services, productivity JEL Classification: F1 F2 ∗International Research, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 33 Liberty Street, New York, NY 10045, email [email protected]; [email protected]. We would like to thank John Romalis, Caroline Freund, Gordon Hanson, Simon Johnson, Jozef Konings, Aart Kraay, Anna Maria Mayda, Christopher Pissarides, Raghu Rajan, Tony Venables, and seminar participants at the IMF, Georgetown University, the US International Trade Commission and the EIIE conference in Lubljana, Slovenia 2005, for helpful comments. We thank Yuanyuan Chen, Jungjin Lee and Evelina Mengova for excellent research assistance. The views expressed in this Working Paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Federal Reserve System or the IMF. 1. -

Outsourcing Tariff Evasion: a New Explanation for Entrepot Trade

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES OUTSOURCING TARIFF EVASION: A NEW EXPLANATION FOR ENTREPOT TRADE Raymond Fisman Peter Moustakerski Shang-Jin Wei Working Paper 12818 http://www.nber.org/papers/w12818 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 January 2007 * Associate Professor, 823 Uris Hall, Graduate School of Business, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027, phone: (212) 854-9157; fax: (212) 854-9895; email:[email protected]. **Senior Associate, Booz Allen Hamilton, 101 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10178, phone: (212) 551-6798, fax: (212) 551-6732, email: [email protected] *** Assistant Director and Chief of the Trade and Investment Division, Research Department, IMF, 700 19th Street NW, Washington, DC 20431, and Research Associate and Director of the Working Group on the Chinese Economy, National Bureau of Economic Research, phone: 202/797-6023, fax: 202/797-6181, [email protected]. www.nber.org/~wei. We thank Jahangir Aziz, Lee Branstetter, Mihir Desai, Martin Feldstein, Wensheng Peng, John Romalis, and participants at NBER and CEPR conferences and a World Bank-IMF joint seminar for helpful comments and Yuanyuan Chen for able research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2007 by Raymond Fisman, Peter Moustakerski, and Shang-Jin Wei. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Outsourcing Tariff Evasion: A New Explanation for Entrepot Trade Raymond Fisman, Peter Moustakerski, and Shang-Jin Wei NBER Working Paper No. -

Outsourcing Tariff Evasion: a New Explanation for Entrepôt Trade

WP/05/102 Revised: 6/3/05 Outsourcing Tariff Evasion: A New Explanation for Entrepôt Trade Raymond Fisman, Peter Moustakerski, and Shang-Jin Wei © 2005 International Monetary Fund WP/05/102 Revised: 6/3/05 IMF Working Paper Research Department Outsourcing Tariff Evasion: A New Explanation for Entrepôt Trade Prepared by Raymond Fisman, Peter Moustakerski, and Shang-Jin Wei1 May 2005 Abstract This Working Paper should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed in this Working Paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy. Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to further debate. Traditional explanations for indirect trade carried out through an entrepôt have focused on savings in transport costs and on the role of specialized agents in processing and distribution. We provide an alternative perspective based on the possibility that entrepôts may facilitate tariff evasion. Using data on direct exports to mainland China and indirect exports to it via Hong Kong SAR, we find that the indirect export rate rises with the Chinese tariff rate, even though there is no legal tax advantage to sending goods via Hong Kong SAR. We undertake a number of extensions to rule out plausible alternative hypotheses. JEL Classification Numbers: H2, F1 Keywords: Tax Evasion, Indirect Trade, Corruption Author(s) E-Mail Address: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 1 The authors would like to thank Jahangir Aziz, John Romalis, Lee Branstetter, and participants in a National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) conference and a World Bank-IMF joint seminar for helpful comments and Yuanyuan Chen for able research assistance. -

Customs Compliance Procedures

Since 2014, Irish Traders are required to provide customs CUSTOMS COMPLIANCE authorities with information, by way of an Electronic Manifest Declaration, of all vessels/aircraft PROCEDURES carrying goods into and out of Ireland, both Community and non- Community. The Union Customs Code is in place from May 2016. Penalties have been introduced in the 2011 Finance Act which focuses attention on the administration responsibilities for correct submission of SAD returns. Failure to make correct declarations also brings closer the possibility of a Customs audit. Authorised Economic Operator (AEO) certifications have achieved substantial take up across Europe. Mutual Recognition has been agreed between AEO and CTPAT in the USA. However Ireland AEO certification is lagging far behind other EU countries. Lack of AEO certification may encounter delays in clearance by Customs. Course Objectives Feedback from This two day course provides the Exporting, Importing and our participants Logistics companies with a has been valuable update to International Trade excellent in Documentation, Customs, VIES 11 Merrion Square - & INTRASTAT Procedures. Dublin 2 - Ireland assisting them with their Target Audience [email protected] This course is a must for Brexit issues. those management and operational personnel needing +353 (1) 676 6894 to become familiar with Austin Rutledge Customs developments. www.export-edge.com CEO / Educational Course Benefit Director Assurance A detailed review of your customs and trade issues will take place with a pre-course -

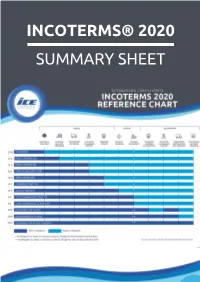

INCOTERMS® 2020 SUMMARY SHEET Note That Clause a Still Excludes Coverage in a Range of Circumstances, Such As War and Strikes

INCOTERMS® 2020 SUMMARY SHEET Note that Clause A still excludes coverage in a range of circumstances, such as war and strikes. Further, all cargo insurance generally excludes coverage for consequential loss (flow-on effects such as loss of profit or loss of opportunity as a result of lost or damaged goods, for example). Is it worth increasing costs with higher premiums for wider coverage? Or is better to expose your cargo to further risk at a more affordable premium? Consider which cargo insurance policy is more appropriate for your business goals. INCLUSION OF SECURITY REQUIREMENTS Incoterms® 2020 makes security obligations more prominent. Screening of containers in certain circumstances is now compulsory. New provisions in Incoterms® 2020 distribute security responsibilities between vendor and purchaser, so it is critical to review where each party is responsible and what measures must be introduced. MOVEMENT OF GOODS BY OWN TRANSPORTATION Incoterms® 2020 now enable that parties to use their own transport for carrying goods, rather than outsourcing transport to a third-party carrier (which had been assumed in Incoterms® 2010). The FCA, DAP, DPU and DDP have been updated to reflect this clarification. CHANGING THE WORDING OF THE INCOTERMS DOCUMENT Incoterms® 2020 have been reworded to make it more relevant and more easily understood. Now there are explanatory notes outlining the fundamental nature of each of the Incoterms®. Costs are better presented, creating an easy list of costs all in one place. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS It’s really important that both importers and exporters pay close attention their contract of sale. The Incoterm used needs to align with all the other terms used in the contract which deal with things like transportation and finance. -

The Benefits and Costs of Outsourcing Jobs

The Park Place Economist Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 10 March 2008 Opinion: The Benefits and Costs of Outsourcing Jobs George Coontz '04 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/parkplace Recommended Citation Coontz '04, George (2004) "Opinion: The Benefits and Costs of Outsourcing Jobs," The Park Place Economist: Vol. 12 Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/parkplace/vol12/iss1/10 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Opinion: The Benefits and Costs of Outsourcing Jobs This article is available in The Park Place Economist: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/parkplace/vol12/iss1/10 Opinion: The Benefits and Costs of Outsourcing Jobs George Coontz With today’s consumer stretching the dollar try, then this country possesses the comparative ad- further and further, tremendous competitive pres- vantage. This country should elect to produce this sure has been put on U.S. companies trying to com- good or service, while the other country should pro- pete with foreign companies. -

Pre-Empting Protectionism in Services: the Gats and Outsourcing

3B2 Version 8.07i/W (Oct 12 2004) J:/3B2/Oxford University Press/Journals/JIEL/Vol 7-4/002Mattoo.3d Journal of International Economic Law 7(4), 765–800 pre-empting protectionism in services: the gats and outsourcing Aaditya Mattoo* and Sacha Wunsch-Vincent** abstract Cross-border trade in services is growing rapidly, with both developed and developing countries among the most dynamic exporters. Despite the substantial global benefits from such trade, the adjustment pressures created in importing countries could provoke a protectionist backlash – some signs of which are already visible in procurement and regulatory restrictions. The current negotiations under the Doha Development Agenda offer an opportunity to lock in current openness and pre-empt protectionism. This note describes how a bold initiative under the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) can help secure openness. introduction Cross-border trade in business services, especially the so-called ‘IT-enabled services’, is today among the fastest growing areas of international trade.1 While the industrial countries are the largest exporters of such services, some of the most dynamic exporters are developing countries. Three factors are responsible for this phenomenon. First, advances in technology have made cross-border trade possible in a number of services that were previously only tradeable through the movement of providers. Second, substantial investment in education in a number of developing countries has created a relative abundance of skilled labor, and the absence of commensurate employment opportunities has ensured its availability at a relatively low wage. Finally, * Lead Economist, World Bank, 1818 H St NW, Washington, DC, USA; [email protected] ** Economist, OECD/Visiting Fellow Institute for International Economics, OECD – STI, Informa- tion, Computer and Communications Policy (ICCP), 2 rue Andre´ Pascal, F-75775 Paris Cedex 16; [email protected]. -

Overview of the Activities Performed by EUGBC in 2014 and Plans in 2015

Overview of the activities performed by EUGBC in 2014 and plans in 2015 EUGBC was engaged to accomplish following dimensions during 2014: EUGBC Members meeting with Georgian Government Officials: 7 February: Alex Petriashvili, State Minister for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration 11 March: Tamar Beruchashvili, Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister 2 June: Mikheil Janelidze, Deputy Minister of Economy 30 July: Mikheil Janelidze, Deputy Minister of Economy 5 September: Ioseb Nanobashvili, Director, Department for International Economic Relations, MFA 22 October: Giorgi Kvirikashvili, Vice Prime Minister and Minister of Economy 17 December: David Bakradze, State Minister for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration 23 December: Gigi Gigiadze, Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister EUGBC Members meeting with the EU officials: 22 January: Dirk Schuebel, Head of Division, Eastern Partnership Bilateral, European External Action Service (Tbilisi) 26 March: Philippe Cuisson, EU Chief Negotiator of DCFTA with Georgia (Tbilisi) 7 May: Gunnar Wiegand, Director Russia, Eastern Partnership, Central Asia, Regional Cooperation and OSCE, European External Action Service (Brussels) 7 May: Gunther Sleeuwagen, Director Eastern, Central and South Eastern Europe, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Belgium (Brussels) 7 May: Magdalena Grono, Member of Cabinet of ENP Commissioner (Brussels) 16 September: Andrzej Adamczyk, the President of the EESC Eastern European Neighbors Follow-up Committee, European Economic and Social Committee (Tbilisi) 25 November: Nele Eichhorn, Member -

Countering Information War – Lessons Learned from NATO and Partner Countries”

“Countering Information War – Lessons Learned from NATO and Partner Countries” Expert Workshop in Tbilisi September 27 – 28, 2016 Venue: NATO Liaison Office in Georgia, Tsinamdzgvrishvili street No. 162 DAY 0, MONDAY, 26 SEPTEMBER Arrival of participants 20:00 – 23:00 WELCOME DINNER (IN THE SHADOW OF METEKHI, 29A QUEEN KETEVAN AVE) DAY 1, TUESDAY, 27 SEPTEMBER 9:30 – 10:00 REGISTRATION OF PARTICIPANTS 10:00 – 10:30 OFFICIAL OPENING KETEVAN CHACHAVA, Director, Information Center on NATO and EU, Georgia WILLIAM LAHUE, Head of the NATO Liaison Office in Georgia/ NATO Liaison Officer in South Caucasus, Georgia DANIEL MILO, Head of Strategic Communication Initiative, GLOBSEC Policy Institute, Slovak Republic 10:30 – 11:30 SESSION 1: CONVENTIONAL WAR: INTERNATIONAL CONTROL OF NARRATIVE What are the lessons learned from recent armed conflicts when it comes to their information war components? How was propaganda used to influence the perception of good and evil in the armed conflict by the public at the national and international levels? What needs to be done to improve our resilience from illicit propaganda narratives, especially in the early phases of the armed conflict? COLONEL AIVAR JAESKI, Deputy Director, NATO Center of Excellence for Strategic Communication in Riga, Latvia TORNIKE NOZADZE, Head of the Strategic Communication Department, State Ministry of Georgia for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration Led by: BRIAN WHITMORE, Senior Russia Analyst, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Prague 11:30 – 12:00 COFFEE BREAK 12:00 – 13:30 SESSION