Agency in Photographic Self-Portraits: Charles Lutwidge Dodgson and the Exposure of the Camera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Victorian Photography

THE ART OF VICTORIAN Dr. Laurence Shafe [email protected] PHOTOGRAPHY www.shafe.uk The Art of Victorian Photography The invention and blossoming of photography coincided with the Victorian era and photography had an enormous influence on how Victorians saw the world. We will see how photography developed and how it raised issues concerning its role and purpose and questions about whether it was an art. The photographic revolution put portrait painters out of business and created a new form of portraiture. Many photographers tried various methods and techniques to show it was an art in its own right. It changed the way we see the world and brought the inaccessible, exotic and erotic into the home. It enabled historic events, famous people and exotic places to be seen for the first time and the century ended with the first moving images which ushered in a whole new form of entertainment. • My aim is to take you on a journey from the beginning of photography to the end of the nineteenth century with a focus on the impact it had on the visual arts. • I focus on England and English photographers and I take this title narrowly in the sense of photographs displayed as works of fine art and broadly as the skill of taking photographs using this new medium. • In particular, • Pre-photographic reproduction (including drawing and painting) • The discovery of photography, the first person captured, Fox Talbot and The Pencil of Light • But was it an art, how photographers created ‘artistic’ photographs, ‘artistic’ scenes, blurring, the Pastoral • The Victorian -

“The Two Ways of Life” Progetto a Cura Di Elisa Mantovani 3°F Tecnico Grafico A.S

“The two ways of life” Progetto a cura di Elisa Mantovani 3°F Tecnico Grafico a.s. 2016/17 Oscar Gustave Rejlander è stato uno dei personaggi più bizzarri e controversi fra quelli che hanno assistito in prima persona alla scoperta della fotografia, ma soprattutto fra coloro che hanno praticato, sperimentato e vissuto questa nuova forma di espressione. Nasce in Svezia, probabilmente nel 1813, figlio di uno scalpellino che è anche ufficiale dell’esercito svedese; viene a Roma per studiare arte e a partire dal 1840 si stabilisce nella città inglese di Lincoln. Si avvicina alla neonata fotografia durante la seconda metà degli anni Quaranta, in circostanze non del tutto chiarite, pare attraverso la conoscenza di uno degli assistenti di William Henry Fox Talbot. Ciò lo porta ad abbandonare progressivamente la pittura per dedicarsi alla nuova arte ed apre uno studio fotografico a Wolverhampton. Nel corso dei primi anni Cinquanta apprende la tecnica del collodio umido, iniziando a produrre immagini ancora poco convenzionali per l’epoca, alcune di contenuto esplicitamente erotico, nelle quali sono ritratti anche ragazzi di strada e giovanissime prostitute. Nel 1855 partecipa con alcune fotografie all’Esposizione Universale di Parigi, ma la notorietà arriva nel 1857 con l’opera per la quale è più conosciuto, The Two Ways of Life. Rejlander era stato uno dei primi a sperimentare la tecnica del fotomontaggio ed è appunto in tal modo che realizza questo suo lavoro, un’immagine di 30 x 16 pollici, (cm 76 x 40 circa), ottenuta dalla stampa di 32 diversi negativi; si tratta di una composizione chiaramente ispirata dal dipinto di Raffaello “La scuola di Atene”, nella quale vengono raffigurati due diversi modi di vita: da un lato la saggezza, la religione, l’operosità e la virtù, dall’altro il gioco d’azzardo, il vino, la dissolutezza e la sensualità. -

Photography and the Art of Chance

Photography and the Art of Chance Photography and the Art of Chance Robin Kelsey The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, En gland 2015 Copyright © 2015 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First printing Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Kelsey, Robin, 1961– Photography and the art of chance / Robin Kelsey. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-74400-4 (alk. paper) 1. Photography, Artistic— Philosophy. 2. Chance in art. I. Title. TR642.K445 2015 770— dc23 2014040717 For Cynthia Cone Contents Introduction 1 1 William Henry Fox Talbot and His Picture Machine 12 2 Defi ning Art against the Mechanical, c. 1860 40 3 Julia Margaret Cameron Transfi gures the Glitch 66 4 Th e Fog of Beauty, c. 1890 102 5 Alfred Stieglitz Moves with the City 149 6 Stalking Chance and Making News, c. 1930 180 7 Frederick Sommer Decomposes Our Nature 214 8 Pressing Photography into a Modernist Mold, c. 1970 249 9 John Baldessari Plays the Fool 284 Conclusion 311 Notes 325 Ac know ledg ments 385 Index 389 Photography and the Art of Chance Introduction Can photographs be art? Institutionally, the answer is obviously yes. Our art museums and galleries abound in photography, and our scholarly jour- nals lavish photographs with attention once reserved for work in other media. Although many contemporary artists mix photography with other tech- nical methods, our institutions do not require this. Th e broad affi rmation that photographs can be art, which comes after more than a century of disagreement and doubt, fulfi lls an old dream of uniting creativity and industry, art and automatism, soul and machine. -

Shires Final for Print.Pdf (3.955Mb)

VICTORIAN CRITICAL INTERVENTIONS Donald E. Hall, Series Editor Shires_Final for Print.indb 1 6/22/2009 3:43:07 PM Shires_Final for Print.indb 2 6/22/2009 3:43:07 PM PERSPECTIVES Modes of Viewing and Knowing in Nineteenth-Century England Linda M. Shires THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PREss Columbus Shires_Final for Print.indb 3 6/22/2009 3:43:08 PM Copyright © 2009 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shires, Linda M., 1950– Perspectives : modes of viewing and knowing in nineteenth-century England / Linda M. Shires. p. cm. — (Victorian critical interventions) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1097-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1097-X (cloth : alk. paper) 1. English poetry—19th century—History and criticism—Theory, etc. 2. Literature and society—England—History—19th century. 3. Optics in literature. 4. Photography in lit- erature. 5. Subjectivity in literature. 6. Objectivity in literature. I. Title. PR595.O6P47 2009 821'.8093552—dc22 2008051411 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1097-0) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9193-1) Cover design by Dan O'Dair. Text design and typesetting by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Type set in Adobe Palatino. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Shires_Final for Print.indb 4 6/22/2009 3:43:08 PM For U. -

Report Case Study 25

Case 13, 2014-15: The Rejlander Album Expert adviser’s statement Reviewing Committee Secretary’s note: Please note that any illustrations referred to have not been reproduced on the Arts Council England Website EXECUTIVE SUMMARY An album containing seventy portrait and figurative albumen print photographs by Oscar Rejlander, taken between c.1856 and 1866. The prints are mounted on gilt-edged card leaves in an album with gilt and tooled black morocco bindings. Sitters include Rejlander himself, his wife, Mary, Sir Henry Taylor, Hallam Tennyson (son of Lord Alfred Tennyson), John and Minnie Constable and other, so-far unidentified, subjects. Oscar Gustav Rejlander (1813-1875), sometimes known as ‘The Father of Art Photography’, was born in Sweden and studied art in Rome, settling in England in the 1840s. He lived in Lincoln and later Wolverhampton, working as an artist and portrait miniaturist. He took an active interest in photography, seeing its potential for assisting artists and in 1853 attended lessons in the London studio of Nicolaas Henneman. This inspired him to develop his own techniques experimenting with portraiture, although it is his pioneering work in combination printing - combining several negatives to form one image - that brought him wider renown. In 1856 Rejlander became a member of the Photographic Society (later the Royal Photographic Society). He wrote extensively for photographic journals and his work was frequently shown in exhibitions. In 1862 Rejlander moved to London where he built a photographic studio designed to make the best use of natural light for his subjects. During his work he came into contact with other prominent contemporary photographers, including Julia Margaret Cameron, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll), Clementina, Lady Hawarden and Charles Darwin. -

Annual Report for 2016/17

ART FUND IN 2016/ 17 We know these are difficult times for UK museums and that, for many, the future looks uncertain. Over the past year our work – not just as a funder, but also as an advocate of and ally to arts organisations – has never seemed more important, or more crucial. Art Fund is an independent charity and does not receive government funding. In 2016 our income totalled £15.2m (up from £14.8m in 2015) and so, rather than cutting back, we began investing in activities to extend our membership and increase the funds we raise. This will mean we are able to do even more to support museums in the years ahead. In 2016 we gave over £4.7m in acquisition grants to help museums build their collections, 75% of which were awarded to organisations outside CONTENTS London. We have seen our support have a real impact. The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, for example, became the first UK museum to own a work by a Czech Surrealist, Toyen’s The Message of the Forest, while the Bowes Museum acquired a rare and important picture from the workshop of the pioneering painter Dieric Bouts the Elder that would have otherwise been sold to a buyer abroad. Page 2 BUILDING COLLECTIONS We also continued to fund development opportunities for curators across The acquisitions we support the UK, fulfilling a need that many museum budgets cannot meet. This year we helped curators travel to six of the seven continents to carry out Page 18 DEVELOPING TALENT 3 vital research for their exhibitions or collections through our Jonathan 4 Ruffer Curatorial Grants programme. -

L-G-0002933919-0005511874.Pdf

Victorian Literature Wiley Blackwell Anthologies Editorial Advisers Rosemary Ashton, University of London; Gillian Beer, University of Cambridge; Gordon Campbell, University of Leicester; Terry Castle, Stanford University; Margaret Ann Doody, Vanderbilt University; Richard Gray, University of Essex; Joseph Harris, Harvard University; Karen L. Kilcup, University of North Carolina, Greensboro; Jerome J. McGann, University of Virginia; David Norbrook, University of Oxford; Tom Paulin, University of Oxford; Michael Payne, Bucknell University; Elaine Showalter, Princeton University; John Sutherland, University of London. Wiley Blackwell Anthologies is a series of extensive and comprehensive volumes designed to address the numerous issues raised by recent debates regarding the literary canon, value, text, context, gender, genre, and period. While providing the reader with key canonical writings in their entirety, the series is also ambitious in its coverage of hitherto marginalized texts, and flex- ible in the overall variety of its approaches to periods and movements. Each volume has been thoroughly researched to meet the current needs of teachers and students. Old and Middle English c.890–c.1450: Victorian Women Poets: An Anthology An Anthology. Third Edition edited by Angela Leighton and Margaret Reynolds edited by Elaine Treharne Victorian Literature: An Anthology Medieval Drama: An Anthology edited by Victor Shea and William Whitla edited by Greg Walker Modernism: An Anthology Chaucer to Spenser: An Anthology of edited by Lawrence Rainey English Writing 1375–1575 The Literatures of Colonial America: edited by Derek Pearsall An Anthology Renaissance Literature: An Anthology edited by Susan Castillo and of Poetry and Prose. Second Edition Ivy T. Schweitzer edited by John C. Hunter African American Literature: Volume 1, 1746–1920 Renaissance Drama: An Anthology edited by Gene Andrew Jarrett of Plays and Entertainments. -

Press Release

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: January 28, 2019 MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Alexandria Sivak Getty Communications (310) 440-6473 [email protected] GETTY MUSEUM PRESENTS FIRST MAJOR EXHIBITION OF THE WORK OF OSCAR G. REJLANDER Oscar Rejlander: Artist Photographer explores the life and work of one of the most influential photographers of the 19th century At the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center March 12–June 9, 2019 LEFT: Eh!, negative about 1854 - 1855; print about 1865, Oscar Gustave Rejlander (British, born Sweden, 1813 - 1875). Albumen silver print. Image: 8.9 × 5.9 cm (3 1/2 × 2 5/16 in.). 84.XM.845.14. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles CENTER: Poor Jo, negative before 1862; print after 1879, Oscar Gustave Rejlander (British, born Sweden, 1813 - 1875). Carbon print. Image: 20.3 × 15.7 cm (8 × 6 3/16 in.). EX.2019.5.5. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Purchased 1993 (37076). National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Photo: NGC. RIGHT: Enchanted by a Parrot, about 1860, Oscar Gustave Rejlander (British, born Sweden, 1813 - 1875). Albumen silver print. Image (approx.): 50 × 30 cm (19 11/16 × 11 13/16 in.). William T. Hillman Collection, New York. Photo: Hans P. Kraus, Jr., New York LOS ANGELES – Oscar G. Rejlander (British, born Sweden, 1813-1875) was one of the 19th century’s greatest innovators in the medium of photography, counting Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, Charles Darwin, Lewis Carroll and Julia Margaret Cameron among his devotees. Nevertheless, the extent of Rejlander’s work and career has often been overlooked. -

A Photographer Develops: Reading Robinson, Rejlander, and Cameron

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-5-2014 12:00 AM A Photographer Develops: Reading Robinson, Rejlander, and Cameron Jonathan R. Fardy The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Sharon Sliwinski The University of Western Ontario Joint Supervisor Helen Fielding The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Theory and Criticism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Jonathan R. Fardy 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Fardy, Jonathan R., "A Photographer Develops: Reading Robinson, Rejlander, and Cameron" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2486. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2486 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PHOTOGRAPHER DEVELOPS: READING ROBINSON, REJLANDER, AND CAMERON (Thesis format: Monograph) by Jonathan R. Fardy Graduate Program in Theory and Criticism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Jonathan R. Fardy 2014 i Abstract This study examines the historical emergence of the photographer by turning to the writings of three important photographers of the nineteenth century: Henry Peach Robinson (1830-1901), Oscar Gustave Rejlander (1813-1875), and Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879). The photographic works of each of these photographers has been the subject of much historical and interpretive analysis, but their writings have yet to receive significant scholarly attention. -

Maker List This Alphabetized List Includes the Names and Life Dates of All Photographers Whose Work Is Represented in the Collection of the J

Department of Photographs Maker List This alphabetized list includes the names and life dates of all photographers whose work is represented in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum as of December 2006. The number in bold following each maker’s name indicates the number of works by that maker currently held in the collection. To inquire whether a particular photograph is available for viewing in the Photographs Study Room in the Department of Photographs in the J. Paul Getty Museum, please call (310) 440-6589 or send a fax to (310) 440-7743. A–Z Index A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A A. & J. Bool (British, active 1870s) 1 Aalborg (Danish, active about 1909) 1 and Berenice Abbott (American, 1898–1991) 31 Abdullah Frères (Turkish, active Beyazit, Pera, and Cario, 1850s–1900s) 7 Mione Abel (French, active Paris, France about 1896–1920) 2 Abell & Priest (active 1870–1890) 1 Ansel Adams (American, 1902–1984) 39 Eddie Adams (American, 1933–2004) 3 Mac Adams (American, born 1943) 1 Marcus Adams (British, 1875–1959) 1 Robert Adams (American, born 1937) 93 Antoine Samuel Adam-Salomon (French, 1818–1881) 2 Prescott Adamson (American, active Philadelphia, Pennsylvania about 1900) 1 and Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821–1848) 1 J. Adcock (British, active Bath, England about 1903) 1 Robert (Bob) Adelman (American, born 1930) 5 Mehemed Fehmy Agha (American, born Russia, 1896–1978) 3 Comte Olympe Aguado (French, 1827–1894) 13 Onèsipe Aguado (Vicomte) (French, 1831–1893) 1 Alicia Ahumada (Mexican, born 1956) 1 Franz J. -

XRP Box List for PDF ER and DC Edits

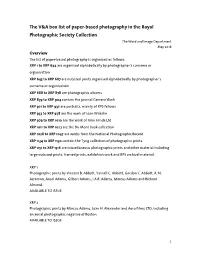

The V&A box list of paper-based photography in the Royal Photographic Society Collection The Word and Image Department May 2018 Overview The list of paper-based photography is organised as follows: XRP 1 to XRP 644 are organised alphabetically by photographer’s surname or organisation XRP 645 to XRP 687 are outsized prints organised alphabetically by photographer’s surname or organisation XRP 688 to XRP 878 are photographic albums XRP 879 to XRP 904 contain the journal Camera Work XRP 921 to XRP 932 are portraits, mainly of RPS fellows XRP 933 to XRP 978 are the work of Joan Wakelin XRP 979 to XRP 1010 are the work of John Hinde Ltd XRP 1011 to XRP 1027 are the Du Mont book collection XRP 1028 to XRP 1047 are works from the National Photographic Record XRP 1134 to XRP 1150 contain the Tyng collection of photographic prints XRP 1151 to XRP 1516 are miscellaneous photographic prints and other material including large outsized prints, framed prints, exhibition work and RPS archival material. XRP 1 Photographic prints by Vincent B. Abbott, Yarnall C. Abbott, Gordon C. Abbott, A. N. Acraman, Ansel Adams, Gilbert Adams, J.A.R. Adams, Marcus Adams and Richard Almond. AVAILABLE TO ISSUE XRP 2 Photographic prints by Marcus Adams, Joan H. Alexander and Aero Films LTD, including an aerial photographic negative of Boston. AVAILABLE TO ISSUE 1 XRP 3 Photographic prints by John. H. Ahern, Rao Sahib Aiyar, G.S. Akaksu, W.A. Alcock, R.F. Alderton, L.E. Aldous, Edward Alenius, B. Alfieri (snr), B. -

A New Form of Expression: Julia Margaret Cameron's Photographic Illustrations of Alfred Lord Tennyson's Poetry Hannah Sother

A New Form of Expression: Julia Margaret Cameron’s Photographic Illustrations of Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Poetry Hannah Sothern Abstract This article considers how the early British photographer Julia Margaret Cameron used the aesthetic language of the Pre-Raphaelites to illustrate Tennyson’s Idylls of the King and Other Poems, and looks at how Tennyson’s poem The Lady of Shalott had a vast impact on visual culture of the time. Since the advent of photography, interesting debates have arisen about its place within the hierarchy of the arts in the Victorian era. Figure 1. Julia Margaret Cameron, The Parting of Lancelot and Guinevere (1874). Albumen silver print from glass, 33.2 × 28.8cm. David Hunter McAlpin Fund, 1952. © Metropolitan Museum of Art OASC permissions. 53 Vides III 2015 Taking their cue from Ruskin and the developing art of photography, the Pre-Raphaelites can be seen to capture nuances and detail in their paintings. In turn, their art affected photographers who looked for structure and subject matter for this new medium, thus a dialogue was formed between these two forms of art, meaning the traditional approach to making pictures was completely overturned.1 It is important to consider this connection as it reveals how the two art forms merged and interacted with one another, as well as challenging the narrative we are told about modern art. Pre-Raphaelitism is often perceived as a ‘literary’ art form, and indeed the movement was greatly influenced by contemporary poets such as Shelley, Keats and Tennyson, in addition to medieval manuscripts and Arthurian legend.