Philosophy and the Professional Image of Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy and the Black Experience

APA NEWSLETTER ON Philosophy and the Black Experience John McClendon & George Yancy, Co-Editors Spring 2004 Volume 03, Number 2 elaborations on the sage of African American scholarship is by ROM THE DITORS way of centrally investigating the contributions of Amilcar F E Cabral to Marxist philosophical analysis of the African condition. Duran’s “Cabral, African Marxism, and the Notion of History” is a comparative look at Cabral in light of the contributions of We are most happy to announce that this issue of the APA Marxist thinkers C. L. R. James and W. E. B. Du Bois. Duran Newsletter on Philosophy and the Black Experience has several conceptually places Cabral in the role of an innovative fine articles on philosophy of race, philosophy of science (both philosopher within the Marxist tradition of Africana thought. social science and natural science), and political philosophy. Duran highlights Cabral’s profound understanding of the However, before we introduce the articles, we would like to historical development as a manifestation of revolutionary make an announcement on behalf of the Philosophy practice in the African liberation movement. Department at Morgan State University (MSU). It has come to In this issue of the Newsletter, philosopher Gertrude James our attention that MSU may lose the major in philosophy. We Gonzalez de Allen provides a very insightful review of Robert think that the role of our Historically Black Colleges and Birt’s book, The Quest for Community and Identity: Critical Universities and MSU in particular has been of critical Essays in Africana Social Philosophy. significance in attracting African American students to Our last contributor, Dr. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... The Habits of Racism: A Phenomenology of the Lived Experience of Racism and Racialised Embodiment. A Dissertation Presented by Helen Ngo to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy Stony Brook University May 2015 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Helen Ngo We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Anne O'Byrne – Dissertation Co-Advisor Associate Professor of Philosophy, Department of Philosophy Edward S. Casey – Dissertation Co-Advisor Distinguished Professor of Philosophy, Department of Philosophy Eduardo Mendieta – Chairperson of Defense Professor of Philosophy, Department of Philosophy Alia Al-Saji – External Reader Associate Professor of Philosophy, Department of Philosophy (McGill University) George Yancy – External Reader Professor of Philosophy, Department of Philosophy (Duquesne University) This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation The Habits of Racism: A Phenomenology of the Lived Experience of Racism and Racialised Embodiment. by Helen Ngo Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy Stony Brook University 2015 This dissertation examines some of the complex questions raised by the phenomenon and experience of racism. My inquiry is twofold: First, drawing on the resources of Merleau-Ponty, I argue that the conceptual reworking of habit as bodily orientation helps us to identify the more subtle but fundamental workings of racism, to catch its insidious, gestural expressions, as well as its habitual modes of racialised perception. -

Philosophy News • Spring 2016 Duq.Edu/Philosophy

Duquesne Graduate Philosophy News • Spring 2016 duq.edu/philosophy Department of Philosophy 600 Forbes Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15282 PhilosophyDepartment GRADUATE NEWS • SPRING 2017 VOLUME 9, ISSUE 1 Department News This has been another successful and stimulating year for the secured a Diversity Project Grant from Hypatia: a feminist philosophy Philosophy Department. We are happy to announce the promotion journal in support of the D-WiP conference. of Dr. Jennifer Bates to Professor in Fall 2016, and in Spring 2017, the promotion of Dr. Jay Lampert to Professor and Dr. Tom Eyers to Our recent alumni have also had a busy year. Associate Professor. Jim Bahoh, Ph.D. ’16, was awarded a prestigious VolkswagenStiftung/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Renowned philosopher Dr. Simon Critchley (New School for Social Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of Bonn. GRADUATE NEWS continued from inside Research) visited Duquesne University on November 17–18 to give There, he will work on a new research project with a seminar for the Simon Silverman Phenomenology Center’s 35th the heading, “The Critique of Representation in JACOB GREENSTINE, “Diverging Ways: The Trajectories of MARTIN KRAHN, “The Structure of Logical and Natural Concepts Annual Symposium “Life, Death and Play: Philosophy in Literature, German Idealism: The Historical and Systematic Ground of Recent Ontology in Parmenides, Aristotle, and Deleuze,” Contemporary in Hegel’s System,” October 14. Sport and Psychoanalysis.” Ontologies of ‘Events.’” More specifically, this project will examine Encounters with Ancient Metaphysics, ed. Jacob Greenstine and TREY WEISE, “Reading Wordsworth’s ‘Prelude’ with Adorno’s the relation between Heidegger and Deleuze’s theories of events on Ryan Johnson, 2017. -

Decolonizing the White Colonizer? by Cecilia Cissell Lucas a Dissertation

Decolonizing the White Colonizer? By Cecilia Cissell Lucas A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Patricia Baquedano-López, Chair Professor Zeus Leonardo Professor Ramón Grosfoguel Professor Catherine Cole Fall 2013 Decolonizing the White Colonizer? Copyright 2013 Cecilia Cissell Lucas Abstract Decolonizing the White Colonizer? By Cecilia Cissell Lucas Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Berkeley Professor Patricia Baquedano-López, Chair This interdisciplinary study examines the question of decolonizing the white colonizer in the United States. After establishing the U.S. as a nation-state built on and still manifesting a colonial tradition of white supremacy which necessitates multifaceted decolonization, the dissertation asks and addresses two questions: 1) what particular issues need to be taken into account when attempting to decolonize the white colonizer and 2) how might the white colonizer participate in decolonization processes? Many scholars in the fields this dissertation draws on -- Critical Race Theory, Critical Ethnic Studies, Coloniality and Decolonial Theory, Language Socialization, and Performance Studies -- have offered incisive analyses of colonial white supremacy, and assume a transformation of white subjectivities as part of the envisioned transformation of social, political and economic relationships. However, in regards to processes of decolonization, most of that work is focused on the decolonization of political and economic structures and on decolonizing the colonized. The questions pursued in this dissertation do not assume a simplistic colonizer/colonized binary but recognize the saliency of geo- and bio-political positionalities. -

Philosophy Catalog August 2013

Philosophy Catalog August 2013 Windows Booksellers 199 West 8th Ave., Suite 1 Eugene, OR 97401 USA Phone: (800) 779-1701 or (541) 485-0014 * Fax: (541) 465-9694 Email and Skype: [email protected] Website: http://www.windowsbooks.com Monday - Friday: 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM, Pacific time (phone & in-store); Saturday: Noon to 3:00 PM, Pacific time (in-store only- sorry, no phone). Our specialty is used and out-of-print academic books in the areas of theology, church history, biblical studies, and western philosophy. We operate an open shop and coffee house in downtown Eugene. Please stop by if you're ever in the area! When ordering, please reference our book number (shown in brackets at the end of each listing). Prepayment required of individuals. Credit cards: Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Discover; or check/money order in US dollars. Books will be reserved 10 days while awaiting payment. Purchase orders accepted for institutional orders. Shipping charge is based on estimated final weight of package, and calculated at the shipper's actual cost, plus $1.00 handling per package. We advise insuring orders of $100.00 or more. Insurance is available at 5% of the order's total, before shipping. Uninsured orders of $100.00 or more are sent at the customer's risk. Returns are accepted on the basis of inaccurate description. Please call before returning an item. __American Catholic Philosophical Association, 40th Annual Meeting, Scholasticism in the Modern World, Statler Hilton Hotel, Washington, D.C., April 11-13, 1966__. 1966. Pamphlet. 60pp. Stapled booklet. -

PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT Pittsburgh, Pa 15282

DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY DUQUESNE UNIVERSITY 600 FORBES AVENUE PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT PITTSBURGH, PA 15282 CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED 3 0 3 DUQUESNE GRADUATE PHILOSOPHY NEWS 2009 • Volume 2, Issue 1 FEATURED GRADUATE STUDENT FACULTY Kamal Shlbei is a doctoral student from Libya. He studied SCHOLARSHIP engineering in Libya, and worked in a cement factory for 10 years, then decided to study philosophy at Elmergib University, one of Libya’s three major universities, specializing in the Dr. Jennifer Bates’ manuscript humanities. He completed a master’s degree there, writing his Hegel and Shakespeare thesis, which has subsequently been published, on the priority on Moral Imagination was of existence over essence in the work of Mulla Sadra. He then accepted for publication by taught philosophy and logic for three years at Asmarya University, State University of New York which provided a grant for doctoral study. Press. Shlbei, his wife and four young children moved to the United Dr. Fred Evans’ monograph States early last year. After ESL study in Oklahoma City, he The Multi-Voiced Body: Society applied to Duquesne. At present, Shlbei is the only Libyan and Communication in the studying graduate philosophy in the United States. Age of Diversity was published by Columbia University Press. He plans to continue working on the problem of existence, particularly in postmodern In addition, Dr. Evans gave thought. In addition, Shlbei is a published poet, with one collection in Arabic entitled a keynote address for the Musica Teptehege Be (Music Enjoys Me). Sixteenth Annual Graduate Philosophy Conference at Kent State University. OINTS OF NTEREST P I Dr. -

APA NEWSLETTER on Philosophy and the Black Experience

NEWSLETTER | The American Philosophical Association Philosophy and the Black Experience SPRING 2020 VOLUME 19 | NUMBER 2 FROM THE EDITORS Stephen C. Ferguson II and Dwayne Tunstall SUBMISSION GUIDELINES AND INFORMATION FOOTNOTES TO HISTORY Joyce Mitchell Cook (1933–2014) ARTICLES Anwar Uhuru Textual Mysticism: Reading the Sublime in Philosophical Mysticism Alfred Frankowski and Michael L. Thomas Spectacle Lynching, Sovereignty, and Genocide: A Dialog with Al Frankowski Leonard Harris Purdue University and President Mitch Daniels: Confession of a Rare Creature VOLUME 19 | NUMBER 2 SPRING 2020 © 2020 BY THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL ASSOCIATION ISSN 2155-9708 APA NEWSLETTER ON Philosophy and the Black Experience STEPHEN C. FERGUSON II AND DWAYNE TUNSTALL, CO-EDITORS VOLUME 19 | NUMBER 2 | SPRING 2020 FROM THE EDITORS For this issue, we begin with our annual “Footnotes to Stephen C. Ferguson II History” spotlighting Joyce Mitchell Cook—the first African NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIVERSITY American woman professional philosopher—who passed away in 2014. Next, we have a contribution from Anwar Dwayne Tunstall Uhuru (Monmouth University). Uhuru’s essay-review of GRAND VALLEY STATE UNIVERSITY Anthony Neal’s 2019 book Howard Thurman’s Philosophical Mysticism: Love against Fragmentation explores Neal’s As co-editors of the newsletter, it is with a deep sense reading of Thurman’s philosophical mysticism and its of sadness that we announce the death of the Black place in African American philosophical history. Next, philosopher Kenneth Allen Taylor (1954–2019), the Henry we have a philosophical dialogue between Michael L. Waldgrave Stuart Professor of Philosophy at Stanford Thomas and Alfred Frankowsi on the relationship between University. -

Lauren Freeman

Lauren Freeman Department of Philosophy • University of Louisville • [email protected] AREAS OF Phenomenology, Bioethics, Feminist Philosophy SPECIALIZATION AREAS OF Philosophy of Emotion, Applied Ethics, History of Philosophy (Ancient) COMPETENCE EDUCATION 2010 Ph.D., Philosophy, Boston University Dissertation: “Ethical Dimensions in Martin Heidegger’s Early Thinking” Committee: Prof. Daniel O. Dahlstrom (director), Charles Griswold, C. Allen Speight, Robert Bernasconi (external reader) 2002 M.A., Arts & Social Sciences, University of Chicago Thesis: “The Failed Quest for Unity in Fichte’s Subjective Idealism and Schelling’s Objective Idealism: Epistemological and Ontological Questions” Committee: Robert Pippin (director), Robert Richards 2001 B.A., Classics, Contemporary Studies; University of King’s College, Halifax, Canada EMPLOYMENT 2013- Assistant Professor, University of Louisville, Department of Philosophy 2010-2013 Assistant Professor (Limited Term), Concordia University, Department of Philosophy 2009-2010 Visiting Assistant Professor, Duquesne University, Department of Philosophy PUBLICATIONS Edited Collections The Phenomenology and Science of Emotions, Special Issue of Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences; Guest Editor (with Andreas Elpidorou) (forthcoming 2014) Refereed JournAl Articles And Book ChApters “Langweile” [Boredom], to appear in The Heidegger Lexicon. Edited by Mark Wrathall; Cambridge University Press (forthcoming 2015) “Defending a Heideggerian Account of Mood.” to appear in Philosophy of Mind -

LSE Review of Books: Book Review: on Race: 34 Conversations in a Time of Crisis Edited by George Yancy Page 1 of 3

LSE Review of Books: Book Review: On Race: 34 Conversations in a Time of Crisis edited by George Yancy Page 1 of 3 Book Review: On Race: 34 Conversations in a Time of Crisis edited by George Yancy In On Race: 34 Conversations in a Time of Crisis, George Yancy brings together scholars to reflect on how race and racism have shaped their careers and intellectual work. The collection is a great example of how scholarly dialogue can contribute to pressing public debate, writes Leonardo Custódio, building bridges between personal experiences of racism and philosophical reflections on race and racism’s implications for everyday life, politics and social relations. On Race: 34 Conversations in a Time of Crisis. George Yancy (ed.). Oxford University Press. 2018. Find this book: As an intellectual activist and a public scholar, the African American philosopher George Yancy has a prolific publication record. In addition to dozens of scholarly books and articles, Yancy regularly engages in public debate by writing outside of traditional academic platforms. Most notably, he has frequently published essays and interviews as part of the column, ‘The Stone’, at the New York Times. His recent book On Race: 34 Conversations in a Time of Crisis follows up some of the intellectual dialogues started at ‘The Stone’. As someone trying to balance research and activism in my own work, I believe Yancy’s book is a great example of how scholarly dialogue can contribute to high-quality public debates, especially about essentially contested concepts and topics such as race and racism. As a Brazilian academic researcher leading a new international activist-research project on anti-racism media activism in Finland and abroad, I am often amazed by how public debates on race and racism tend to be similarly contentious in very different contexts. -

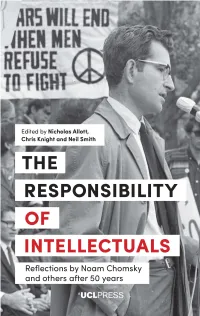

The Responsibility of Intellectuals

The Responsibility of Intellectuals EthicsTheCanada Responsibility and in the FrameAesthetics ofofCopyright, TranslationIntellectuals Collections and the Image of Canada, 1895– 1924 ExploringReflections the by Work Noam of ChomskyAtxaga, Kundera and others and Semprún after 50 years HarrietPhilip J. Hatfield Hulme Edited by Nicholas Allott, Chris Knight and Neil Smith 00-UCL_ETHICS&AESTHETICS_i-278.indd9781787353008_Canada-in-the-Frame_pi-208.indd 3 3 11-Jun-1819/10/2018 4:56:18 09:50PM First published in 2019 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.ucl.ac.uk/ucl-press Text © Contributors, 2019 Images © Copyright holders named in captions, 2019 The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as authors of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non-derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Allott, N., Knight, C. and Smith, N. (eds). The Responsibility of Intellectuals: Reflections by Noam Chomsky and others after 50 years. London: UCL Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.14324/ 111.9781787355514 Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons license unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. -

Black Experience

APA Newsletters Volume 02, Number 2 Spring 2003 NEWSLETTER ON PHILOSOPHY AND THE BLACK EXPERIENCE FROM THE EDITORS, JOHN MCCLENDON & GEORGE YANCY ARTICLES JOHN H. MCCLENDON “Introduction to Drs. Anton Wilhelm Amo and Charles Leander Hill” CHARLES LEANDER HILL “William Ladd, the Black Philosopher from Guinea: A Critical Analysis of His Dissertation on Apathy” GEORGE YANCY “Gilbert Haven Jones as an Early Black Philosopher and Educator” JAMES G. SPADY AND GILES R. WRIGHT “Jean Harvey Slappy’s Philosophy and the Tradition of Marcus Garvey and Thomas W. Harvey” JOHN MCCLENDON “On Assessing the Ideological Impact of Garveyism on Nkrumaism: Political Symbolism Contra Theoretical Substance” STEPHEN C. FERGUSON II “C. L. R. James, Marxism, and Political Freedom” J. EVERET GREEN “Philosophy Born of Struggle Conference Series 1993-2003” BOOK REVIEWS Clarence Shole Johnson: Cornel West & Philosophy REVIEWED BY FLOYD W. H AYES III George Yancy, Ed.: The Philosophical i: Personal Reflections on Life in Philosophy REVIEWED BY DAN WARNER Rodney C. Roberts, Ed.: Injustice and Rectification REVIEWED BY NAOMI ZACK Smokey D. Fontaine and Earl Simmons: E.A.R.L.: The Autobiography of DMX REVIEWED BY JAMES G. SPADY © 2002 by The American Philosophical Association ISSN: 1067-9464 APA NEWSLETTER ON Philosophy and the Black Experience John McClendon & George Yancy, Co-Editors Spring 2003 Volume 02, Number 2 world, and the powerful influences of her great-grandmother ROM THE DITORS and her father, Thomas W. Harvey. John McClendon’s article, F E “On Assessing the Ideological Impact of Garveyism on Nkrumaism: Political Symbolism Contra Theoretical Substance” explores the philosophical divergences between Nkrumah and The editors would like to express their thanks for all of the Garvey’s respective philosophies of Pan-Africanism. -

2016 This Course Proposal Has the Department’S Approval

FIRST-YEAR SEMINAR COURSE PROPOSAL UNIVERSITY OF MARY WASHINGTON Use this form to submit FSEM 100 topics courses for review or any other existing course that you wish to have designated to meet the first-year seminar requirement. COURSE NUMBER: COURSE TITLE: THE STONE: RACISM AND CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PHILOSOPHY SUBMITTED BY: Craig Vasey, Leah Cox DATE: Jan 26 2016 This course proposal has the department’s approval. (Put a check in the box to the right.) X COURSE DESCRIPTION. In the space below, provide a one- to two-sentence description of this course. The description will be entered in Banner and will also be used in other publications about the first-year seminar program (such as the “Eagle Essentials” booklet). This course uses the recent series of interviews with contemporary American philosophers about racism (The Stone, New York Times blog), to explore the current social situation in the US, from color-blindness to “Black Lives Matter.” Students will do research into the theory and practice of ten important contemporary US thinkers. RATIONALE. Include short statement addressing how this course meets the FSEM’s basic components, explaining specifically how it will meet the common FSEM student learning outcomes (see FSEM call above), and arguing why this course should be approved to meet the FSEM General Education requirement. Please point to specific readings, assignments, and exercises and show how they will meet the learning outcomes. In the first week, the students will read the Encyclopedia of Virginia.org documents on eugenics legislation in the 1920’s, which will provide context for appreciating the history of “race,” the problematizing of “race,” the relevance of the Civil Rights Movement, and the intellectual/ academic advances of the last two decades.