The Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Fall Quarter 2018 (October - December) 1 A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

Chopin Day in Rapperswil Organised by the Arthur Rubinstein International Music Foundation, Lodz in Cooperation with the Polish Museum in Rapperswil

Chopin Day in Rapperswil Organised by the Arthur Rubinstein International Music Foundation, Lodz in cooperation with the Polish Museum in Rapperswil “Chopin Day in Rapperswil” will take place in Rapperswil’s medieval castle, which for almost 140 years has housed the Polish Museum. The event, a cultural collaboration between the Rubinstein Foundation and the Polish Museum, marks the 160th anniversa- ry of the death of Frederic Chopin (Paris, 17/10/1849) and the coming 140th anniversary of the founding of the first polish museum – the Polish National Museum in Rapperswill (23/10/1870). We would like raise the profile of Poland’s rich culture in Europe, and we are going to stage the Year of Chopin 2010, which will celebrate the 200th anniversary of Chopin’s birth (Żelazowa Wola, 01/03/1810). We will also celebrate the greatest Polish ‘Chopinist’ (interpreter of Chopin’s works) of the 20th century, Arthur Rubinstein, who was born in Lodz in 1887 and died in Switzerland in 1982, and whose portrait can be seen in the Polish Museum’s Gallery of Distinguished Poles. A week before (17th October 2009) – on the 160th anniversary of Chopin’s death – the foundation is organising “Chopin Day in Lodz”, consisting of a mass, concert and exhibition held in Lodz Cathedral. Please contact the organisers to reserve places and to receive invitations for the events. In inviting everybody to the celebrations and events, we urge those willing to help out finan- cially or with expertise to contact the Rubinstein Foundation. For more information please visit www.arturrubinstein.pl and www.muzeum-polskie.org Town square in front of entrance to castle courtyard, Rapperswil (May 2009, fot. -

Digital Concert Hall

Digital Concert Hall Streaming Partner of the Digital Concert Hall 21/22 season Where we play just for you Welcome to the Digital Concert Hall The Berliner Philharmoniker and chief The coming season also promises reward- conductor Kirill Petrenko welcome you to ing discoveries, including music by unjustly the 2021/22 season! Full of anticipation at forgotten composers from the first third the prospect of intensive musical encoun- of the 20th century. Rued Langgaard and ters with esteemed guests and fascinat- Leone Sinigaglia belong to the “Lost ing discoveries – but especially with you. Generation” that forms a connecting link Austro-German music from the Classi- between late Romanticism and the music cal period to late Romanticism is one facet that followed the Second World War. of Kirill Petrenko’s artistic collaboration In addition to rediscoveries, the with the orchestra. He continues this pro- season offers encounters with the latest grammatic course with works by Mozart, contemporary music. World premieres by Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Olga Neuwirth and Erkki-Sven Tüür reflect Brahms and Strauss. Long-time compan- our diverse musical environment. Artist ions like Herbert Blomstedt, Sir John Eliot in Residence Patricia Kopatchinskaja is Gardiner, Janine Jansen and Sir András also one of the most exciting artists of our Schiff also devote themselves to this core time. The violinist has the ability to capti- repertoire. Semyon Bychkov, Zubin Mehta vate her audiences, even in challenging and Gustavo Dudamel will each conduct works, with enthusiastic playing, technical a Mahler symphony, and Philippe Jordan brilliance and insatiable curiosity. returns to the Berliner Philharmoniker Numerous debuts will arouse your after a long absence. -

A Study of Select World-Federated International Piano Competitions: Influential Actf Ors in Performer Repertoire Choices

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 2020 A Study of Select World-Federated International Piano Competitions: Influential actF ors in Performer Repertoire Choices Yuan-Hung Lin Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Lin, Yuan-Hung, "A Study of Select World-Federated International Piano Competitions: Influential actF ors in Performer Repertoire Choices" (2020). Dissertations. 1799. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1799 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY OF SELECT WORLD-FEDERATED INTERNATIONAL PIANO COMPETITIONS: INFLUENTIAL FACTORS IN PERFORMER REPERTOIRE CHOICES by Yuan-Hung Lin A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Music at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved by: Dr. Elizabeth Moak, Committee Chair Dr. Ellen Elder Dr. Michael Bunchman Dr. Edward Hafer Dr. Joseph Brumbeloe August 2020 COPYRIGHT BY Yuan-Hung Lin 2020 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT In the last ninety years, international music competitions have increased steadily. According to the 2011 Yearbook of the World Federation of International Music Competitions (WFIMC)—founded in 1957—there were only thirteen world-federated international competitions at its founding, with at least nine competitions featuring or including piano. One of the founding competitions, the Chopin competition held in Warsaw, dates back to 1927. -

Helmuth Rilling to Conduct Bach Choral Masterworks

holiday 2006-2007 vol xv · no 4 music · worship · arts Prismyale institute of sacred music common ground for scholarship and practice Helmuth Rilling to Conduct Bach Choral Masterworks Helmuth Rilling, the world renowned conductor, teacher, and Bach scholar, will present a series of lecture/concerts, culminating in a full performance of several choral masterworks of J.S. Bach. The series, entitled Reflections on Bach: Music for Christmas Day 1723, will be presented over three days. The lecture/concerts will consist of talks with musical illustrations, followed by a performance of the work. Part I (Christen, ätzet diesen Tag) will take place on Thursday, January 18 at 8 pm at Sprague Memorial Hall, 470 College St., in New Haven, with Part II (Magnificat in Eb) the following evening (Friday, January 19) at 8pm, also at Sprague Memorial Hall. Tickets for the lecture/concerts are free, and available at 203-432-4158. On Saturday, January 20, there will be a concert performance at 8 pm at Woolsey Hall, corner College and Grove. The concert is free and open to the public; no tickets are required. Helmuth Rilling is known internationally for his lecture/ concerts, as well as for his more than 100 recordings on the Vox, Nonesuch, Columbia, Nippon, CBS, and Turnabout labels. He now records exclusively for Hänssler, for whom he has recorded the complete works of J.S. Bach on 172 CDs. Rilling is the founder of the acclaimed Gächinger Kantorei, the Oregon Bach Festival, the International Bach Academy (Stuttgart), which has been awarded the UNESCO Music Prize, and academies in Buenos Aires, Cracow, Prague, Moscow, Budapest, Santiago de Compostela, and Tokyo. -

Included Services: CHOPIN EXCLUSIVE TOUR / Tour CODE A

Included services: CHOPIN EXCLUSIVE TOUR / Tour CODE A-6 • accommodation at Sofitel Victoria, 5* hotel - Warsaw [4 nights including buffet breakfast] Guaranteed Date 2020 • transportation by deluxe motor coach (up to 49pax) or minibus (up to 19 pax) throughout all the tour • English speaking tour escort throughout all the tour Starting dates in Warsaw Ending dates in Warsaw • Welcome and farewell dinner (3 meals with water+ coffee/tea) Wednesday Sunday • Lunch in Restaurant Przepis na KOMPOT • local guide for a visits of Warsaw October 21 October 25 • Entrance fees: Chopin Museum, Wilanow Palace, POLIN Museum, Żelazowa Wola, Nieborow • Chopin concert in the Museum of Archdiocese • Chocolate tasting • Concert of Finalists of Frederic Chopin Piano Competition • Ballet performance or opera at the Warsaw Opera House Mazurkas Travel Exclusive CHOPIN GUARANTEED DEPARTURE TOUR OCTOBER 21-25 / 2020 Guaranteed Prices 2020 Price per person in twin/double room EUR 992 Single room supplement EUR 299 Mazurkas Travel T: + 48 22 536 46 00 ul. Wojska Polskiego 27 www.mazurkas.com.pl 01-515 Warszawa [email protected] October 21 / 2020 - Wednesday October 22 / 2015 - Thursday October 23 / 2020 - Friday October 24 / 2020 - Saturday WARSAW WARSAW WARSAW WARSAW-ZELAZOWA WOLA- WARSAW (Welcome dinner) (Breakfast) (Breakfast) (Breakfast, lunch & farEwell dinner) After arrival, you will be met and transferred to your hotel in See the Krasinski Palace with the Chopin Drawing Room Morning visit to one of the most splendid residence of Drive to Zelazowa Wola. This is where on February 22, 1810 the heart of the city. where Chopin performed his etudes, some polonaises, and Warsaw, the Wilanow Palace and Royal Gardens. -

Cantus in Choro a GLOBAL VIEW of CHORAL SINGING

Cantus in Choro A GLOBAL VIEW OF CHORAL SINGING The Schola Cantorum performs with Yale Collegium Players All photos courtesy of Yale institute of Sacred Music hen aspiring young singers consider mainstay of European musical life a century ago. Malcolm Bruno visits Wformal musical training, they might look But neither then nor until very recently was there to a college specialising in music or to the music a serious alternative for the professional non- Yale University to find department of a large university, where academic operatic singer. research, performance and music-education could Established in 2004, Yale University’s Schola out about its new be united; though the sine qua non for many still Cantorum is in many ways the template degree remains the conservatoire or Hochschule, those programme for a singer seeking a high-level option Schola Cantorum hallmarks of musical excellence from Naples to to the traditional conservatoire course. I was Paris, Moscow to London and on to New York. delighted, therefore, to be invited recently by its But as we now know them – though tend to forget – director, Simon Carrington, to experience the fruits these conservatories are largely a 19th-century of his two years’ hard labour. ‘I was teaching at invention, designed in an era obsessed with the New England Conservatory in Boston,’ he explains, child protégé, whose principal raison d’être was the ‘when I received a letter from the Yale Institute of fostering of solo as well as rank-and-file talent for Sacred Music announcing its intent to establish a the burgeoning orchestras and opera houses at the new chamber choir specialising in music before A high-level option Choir & Organ November/December 2006 27 ‘For a young aspiring professional the competition for this incredible opportunity increases each year’ 1750 and after 1900 and asking for suggestions of produced able choirs and choir directors, there was someone to develop such a choir as professor of no institution which placed an emphasis on the choral conducting. -

Week 23 Andris Nelsons Music Director

bernard haitink conductor emeritus seiji ozawa music director laureate 2014–2015 Season | Week 23 andris nelsons music director season sponsors Table of Contents | Week 23 7 bso news 13 on display in symphony hall 14 bso music director andris nelsons 16 the boston symphony orchestra 19 casts of character: the symphony statues by caroline taylor 26 this week’s program Notes on the Program 28 The Program in Brief… 29 Dmitri Shostakovich 43 Ludwig van Beethoven 55 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artist 61 Christian Tetzlaff 64 sponsors and donors 80 future programs 82 symphony hall exit plan 83 symphony hall information the friday preview talk on april 3 is given by bso director of program publications marc mandel. program copyright ©2015 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. program book design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photo by Stu Rosner cover design by BSO Marketing BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Symphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, MA 02115-4511 (617)266-1492 bso.org andris nelsons, ray and maria stata music director bernard haitink, lacroix family fund conductor emeritus seiji ozawa, music director laureate 134th season, 2014–2015 trustees of the boston symphony orchestra, inc. William F. Achtmeyer, Chair • Paul Buttenwieser, President • Carmine A. Martignetti, Vice-Chair • Arthur I. Segel, Vice-Chair • Stephen R. Weber, Vice-Chair • Theresa M. Stone, Treasurer David Altshuler • George D. Behrakis • Ronald G. Casty • Susan Bredhoff Cohen, ex-officio • Richard F. Connolly, Jr. • Diddy Cullinane • Cynthia Curme • Alan J. Dworsky • William R. Elfers • Thomas E. Faust, Jr. • Michael Gordon • Brent L. Henry • Susan Hockfield • Barbara W. Hostetter • Charles W. -

Season 2010 Season 2010-2011

Season 20102010----20112011 The Philadelphia Orchestra Thursday, January 6, at 8:00 Friday, January 77,, at 2:00 Saturday, January 88,, at 8:00 Sunday, January 99,, at 2:00 Yannick NézetNézet----SéguinSéguin Conductor Lucy Crowe Soprano Birgit Remmert Mezzo-soprano James Taylor Tenor Andrew FosterFoster----WilliamsWilliams Bass-baritone The Philadelphia Singers Chorale David Hayes Music Director Debussy Nocturnes I. Clouds II. Festivals III. Sirens Intermission Mozart/completed Süssmayr Requiem, K. 626 I. Introitus: Requiem II. Kyrie III. Sequentia 1. Dies irae 2. Tuba mirum 3. Rex tremendae 4. Recordare 5. Confutatis 6. Lacrimosa IV. Offertorium 1. Domine Jesu 2. Hostias V. Sanctus VI. Benedictus VII. Agnus Dei VIII. Communio: Lux aeterna This program runs approximately 1 hour, 45 minutes. The January 6 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. The January 8 concert is sponsored by Ballard Spahr LLP. Since his European conducting debut in 2004, Yannick Nézet-Séguin has become one of the most sought-after conductors on today’s international classical music scene, widely praised by audiences, critics, and artists alike for his musicianship, dedication, and charisma. A native of Montreal, he made his Philadelphia Orchestra debut in 2008 and last June was named the Orchestra’s next music director, a post he takes up with the 2012-13 season. Artistic director and principal conductor of Montreal’s Orchestre Métropolitain since 2000, he became music director of the Rotterdam Philharmonic and principal guest conductor of the London Philharmonic in 2008. Recent engagements have included concerts with the Vienna and Los Angeles philharmonics, the Boston Symphony, the Dresden Staatskapelle, the Orchestre National de France and, earlier this month, a tour with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe and his Berlin Philharmonic debut. -

December 2018 WILL-TV TM Patterns Membership Hotline: 800-898-1065 December 2018 Volume XLVI, Number 6 WILL AM-FM-TV: 217-333-7300 Campbell Hall 300 N

FRIENDS OF WILL MEMBERSHIP MAGAZINE december 2018 WILL-TV TM patterns Membership Hotline: 800-898-1065 december 2018 Volume XLVI, Number 6 WILL AM-FM-TV: 217-333-7300 Campbell Hall 300 N. Goodwin Ave., Urbana, IL 61801-2316 Mailing List Exchange Donor records are proprietary and confidential. WILL does not sell, rent or trade its donor lists. Patterns Friends of WILL Membership Magazine Editor/Art Designer: Sarah Whittington Art Director: Kurt Bielema Printed by Premier Print Group. Printed with SOY INK on RECYCLED, TM Trademark American Soybean Assoc. RECYCLABLE paper. Radio 90.9 FM: A mix of classical music and NPR information programs, including local news. (Also with live streaming on will.illinois.edu.) See pages 4-5. 101.1 FM and 90.9 FM HD2: Locally produced music programs and classical music from C24. (101.1 is available in the Champaign-Urbana area.) See page 6. This time of year often brings about feelings of 580 AM: News and information, NPR, BBC, news, nostalgia for home. We gather with family and agriculture, talk shows. (Also heard on 90.9 FM HD3 with live streaming on will.illinois.edu.) See page 7. friends as we celebrate holidays and the close of another year. The spirit of home surrounds our Television festivities, reminding us of the traditions and WILL-HD values that built our foundations and guide us All your favorite PBS and local programming, in high definition when available. 12.1; Contact your cable or through the coming year. satellite provider for channel information. See pages People often speak to me of the same nostalgia 9-16. -

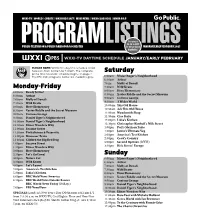

Program Listings

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 See pages 25-30 in CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSfor our program JANUARY/EARLY FEBRUARY 2021 highlights! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE JANUARY/EARLY FEBRUARY PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete Saturday prime time television schedule begins on page 2. The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 8:00am 6:00am Ready Jet Go! Hero Elementary 8:30am 6:30am Arthur Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 9:00am 7:00am Molly of Denali Curious George 9:30am 7:30am Wild Kratts A Wider World 10:00am 8:00am Hero Elementary This Old House 10:30am 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum Ask This Old House 11:00am 9:00am Curious George Woodsmith Shop 11:30am 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Ciao Italia 12:00pm 10:00am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Lidia’s Kitchen 12:30pm 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street 1:00pm 11:00am Sesame Street Pati’s Mexican Table 1:30pm 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific Jamie’s Ulitmate Veg 2:00pm 12:00pm Dinosaur Train America’s Test Kitchen 2:30pm 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog Cook’s Country 3:00pm (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street Second Opinion 3:30pm 1:30pm Elinor Wonders Why Rick Steves’ Europe 2:00pm Hero Elementary 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! Sunday 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:30pm Wild Kratts 6:30am Arthur 4:00pm Let’s Learn! 7:00am Molly of Denali 5:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 7:30am Wild Kratts 5:30pm Lidia’s Kitchen 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:00pm BBC Wold News America 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 6:30pm BBC World News Outside Source 9:00am Curious George BBC World News Today (Fridays) 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 7:00pm PBS NewsHour 10:00am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood SPECIALS: London’s New Year’s Day Celebration 2021 airs 1/1 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why from 7-9:30 a.m. -

Summer 2013 Boston Symphony Orchestra

boston symphony orchestra summer 2013 Bernard Haitink, LaCroix Family Fund Conductor Emeritus, Endowed in Perpetuity Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 132nd season, 2012–2013 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Edmund Kelly, Chairman • Paul Buttenwieser, Vice-Chairman • Diddy Cullinane, Vice-Chairman • Stephen B. Kay, Vice-Chairman • Robert P. O’Block, Vice-Chairman • Roger T. Servison, Vice-Chairman • Stephen R. Weber, Vice-Chairman • Theresa M. Stone, Treasurer William F. Achtmeyer • George D. Behrakis • Jan Brett • Susan Bredhoff Cohen, ex-officio • Richard F. Connolly, Jr. • Cynthia Curme • Alan J. Dworsky • William R. Elfers • Thomas E. Faust, Jr. • Nancy J. Fitzpatrick • Michael Gordon • Brent L. Henry • Charles W. Jack, ex-officio • Charles H. Jenkins, Jr. • Joyce G. Linde • John M. Loder • Nancy K. Lubin • Carmine A. Martignetti • Robert J. Mayer, M.D. • Susan W. Paine • Peter Palandjian, ex-officio • Carol Reich • Arthur I. Segel • Thomas G. Stemberg • Caroline Taylor • Stephen R. Weiner • Robert C. Winters Life Trustees Vernon R. Alden • Harlan E. Anderson • David B. Arnold, Jr. • J.P. Barger • Leo L. Beranek • Deborah Davis Berman • Peter A. Brooke • John F. Cogan, Jr. • Mrs. Edith L. Dabney • Nelson J. Darling, Jr. • Nina L. Doggett • Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick • Thelma E. Goldberg • Mrs. Béla T. Kalman • George Krupp • Mrs. Henrietta N. Meyer • Nathan R. Miller • Richard P. Morse • David Mugar • Mary S. Newman • Vincent M. O’Reilly • William J. Poorvu • Peter C. Read • Edward I. Rudman • Richard A. Smith • Ray Stata • John Hoyt Stookey • Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. • John L. Thorndike • Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas Other Officers of the Corporation Mark Volpe, Managing Director • Thomas D.