When They See Us: a Case Study Exploring Culturally Responsive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

HBO, Sky's 'Chernobyl' Leads 2020 Baftas with 14 Nominations

HBO, Sky's 'Chernobyl' Leads 2020 BAFTAs with 14 Nominations 06.04.2020 HBO and Sky's Emmy-winning limited series Chernobyl tied Killing Eve's record, set last year, of 14 nominations at the 2020 BAFTA TV awards. That haul helped Sky earn a total of 25 nominations. The BBC led with a total of 79, followed by Channel 4 with 31. The series about the nuclear disaster that befell the Russian city was nominated best mini-series, with Jared Harris and Stellan Skarsgård nommed best lead and supporting actor, respectively. Other limited series to score nominations were ITV's Confession, BBC One's The Victim and Channel 4's The Virtues. Netflix's The Crown, produced by Left Bank Pictures, was next with seven total nominations, including best drama and acting nominations for Oscar-winner Olivia Colman, who played Queen Elizabeth, and Helena Bonham Carter, who played Princess Margaret. Also nominated best drama were Channel 4 and Netflix's The End of the F***ig World, HBO and BBC One's Gentleman Jack and BBC Two's Giri/Haji. Besides Colman, dramatic acting nominations went to Glenda Jackson for BBC One's Elizabeth Is Missing, Emmy winner and last year's BAFTA winner Jodie Comer for BBC One's Killing Eve, Samantha Morton for Channel 4's I Am Kirsty and Suranne Jones for Gentleman Jack. Besides Harris, men nominated for lead actor include Callum Turner for BBC One's The Capture, Stephen Graham for The Virtues and Takehiro Hira for Giri/Haji. And besides Carter, other supporting actress nominations went to Helen Behan for The Virtues, Jasmine Jobson for Top Boy and Naomi Ackie for The End of the F***ing World. -

Through the Lens of Critical Race Theory

AN ANALYSIS OF DUVERNAY’S “WHEN THEY SEE US” THROUGH THE LENS OF CRITICAL RACE THEORY by Uwode Ejiro Favour A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Major Subject: Communication West Texas A&M University Canyon, TX May 2020 APPROVED: ___________________________ Date: _____________________ Chairperson, Thesis Committee ___________________________ Date: _______________________ Member, Thesis Committee ___________________________ Date: _______________________ Member, Thesis Committee _________________________________ Date: ___________________ Head, Major Department _________________________________ Date: ___________________ Dean, Graduate School ABSTRACT The film series, When They See Us, has been the most popular four part mini- series on Netflix since its release in 2019. It was produced and directed by Ava DuVernay and it touches upon true events that happened in 1989 at Central Park. The series presents the story of five black and brown boys and their brutal experiences in the hands of the American justice system. Kevin Richardson, Korey Wise, Raymond Santana, Yusef Salam, and Antron McCray were all fourteen to sixteen years old when they were accused of raping and brutalizing Trisha Meili at Central Park. DuVernay crafts scenes that are raw and horrifying but points to the lived experiences of people of color in America. The purpose of this thesis was to explore Ava DuVernay’s movie, When They See Us and its portrayal of the bias nature of the criminal justice system in America against people of color. This study sought to explore the connection of microaggressions and racism to police brutality against people of color in the United States. By using both critical race theory and standpoint theory, the study analyzes the experiences of the men of color in the movie as it relates to racism and judicial inequality, and how this directly reflects the experiences of people of color within the American society. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Running on Empty

RUNNING ON EMPTY RUNNING on EMPTY S.E. Durrant Holiday House New York Text copyright © 2018 by S. E. Durrant Cover art copyright © 2018 by Oriol Vidal First published in the UK in 2018 by Nosy Crow Ltd, London First published in the USA in 2018 by Holiday House, New York All Rights Reserved HOLIDAY HOUSE is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Printed and Bound in July 2018 at Maple Press, York, PA, USA www.holidayhouse.com First American Edition 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Durrant, S. E., author. Title: Running on empty / by S. E. Durrant. Description: First American edition. | New York : Holiday House, 2018. Originally published: London : Nosy Crow Ltd, 2018. | Summary: After his grandfather dies, eleven-year-old AJ, a talented runner, assumes new responsibilities including taking care of his intellectually- challenged parents and figuring out how bills get paid. Identifiers: LCCN 2017035204 | ISBN 9780823438402 (hardcover) Subjects: | CYAC: Family life—England—Fiction. | People with mental disabilities—Fiction. | People with disabilities—Fiction. | Running— Fiction. | Death—Fiction. | Responsibility—Fiction. England—Fiction. Classification: LCC PZ7.1.D875 Run 2018 | DDC [Fic]—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017035204 “It’s no use going back to yesterday, because I was a different person then.” Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll CENTER OF THE UNIVERSE The most amazing thing I ever saw was Usain Bolt winning the 100 meters at the London Olympics. I was there with my mum, dad, and grandad and we were high up in the stadium and I was seven years old and I felt like I was at the center of the universe. -

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020 1 7 Anti-Racist Books Recommended by Educators and Activists from the New York Magazine https://nymag.com/strategist/article/anti-racist-reading- list.html?utm_source=insta&utm_medium=s1&utm_campaign=strategist By The Editors of NY Magazine With protests across the country calling for systemic change and justice for the killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade, many people are asking themselves what they can do to help. Joining protests and making donations to organizations like Know Your Rights Camp, the ACLU, or the National Bail Fund Network are good steps, but many anti-racist educators and activists say that to truly be anti-racist, we have to commit ourselves to the ongoing fight against racism — in the world and in us. To help you get started, we’ve compiled the following list of books suggested by anti-racist organizations, educators, and black- owned bookstores (which we recommend visiting online to purchase these books). They cover the history of racism in America, identifying white privilege, and looking at the intersection of racism and misogyny. We’ve also collected a list of recommended books to help parents raise anti-racist children here. Hard Conversations: Intro to Racism - Patti Digh's Strong Offer This is a month-long online seminar program hosted by authors, speakers, and social justice activists Patti Digh and Victor Lee Lewis, who was featured in the documentary film, The Color of Fear, with help from a community of people who want and are willing to help us understand the reality of racism by telling their stories and sharing their resources. -

Wrongful Conviction Documentaries: Influences of Crime Media Exposure on Mock Juror Decision-Making

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2020 Wrongful Conviction Documentaries: Influences of Crime Media Exposure on Mock Juror Decision-Making Patricia Y. Sanchez The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3939 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 WRONGFUL CONVICTION DOCUMENTARIES: INFLUENCES OF CRIME MEDIA EXPOSURE ON MOCK JUROR DECISION-MAKING by PATRICIA Y. SANCHEZ A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York. 2020 ii © 2020 PATRICIA Y. SANCHEZ All Rights Reserved iii Wrongful Conviction Documentaries: Influences of Crime Media Exposure on Mock Juror Decision-Making by Patricia Y. SancheZ This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in the Psychology program to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______Saul Kassin_______________________ ___________________ _______________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _______Richard Bodnar___________________ ___________________ _______________________________________ Date Executive Officer ________Saul -

9:42 / 9:42 #CNN #News Officer Disputes Netflix Portrayal of Central Park Five Case 360.611 Weergaven •15 Jun

9:42 / 9:42 #CNN #News Officer disputes Netflix portrayal of Central Park Five case 360.611 weergaven •15 jun. 2019 2,3K5,8KDELENOPSLAAN CNN 10,7 mln. abonnees ABONNEREN The Netflix limited series "When They See Us" tells the story of five teen boys of color who were wrongfully convicted in 1990 of raping and leaving a white female jogger for dead in New York City's Central Park. CNN's Michael Smerconish talks with a former NYPD officer who made arrests in the case. #CNN #News MEER WEERGEVEN 9.560 reacties SORTEREN OP Voeg een openbare reactie toe… travisti1 jaar geleden (bewerkt) If they we're so convincingly guilty? Why were they awarded the money by the state? 237 BEANTWOORDEN 68 antwoorden bekijken ——————11 maanden geleden I’m impressed cnn even had this guy on. Whatever actually happened, this doesn’t fit with the cnn narrative. 158 BEANTWOORDEN 47 antwoorden bekijken ms_Coco Spice2 maanden geleden In Korey Wise's "confession tape" at 29:39 you can clearly hear the scream of another boy saying "Stop, you're breaking my arm" look it up! They're not old enough to smoke, drink or vote but can sign away their right to legal counsel and be questioned for hours without their parents?? There's a special place in hell for all the grown people involved in violating these kids 9 BEANTWOORDEN Officer disputes Netflix portrayal of Central Park Five case 1 2 antwoorden bekijken Y B1 jaar geleden (bewerkt) 5:19 "Kevin Richardson had a scratch on his face" 9:13 "If you look at those pictures not one of them has a scratch on them" LIAR! 111 BEANTWOORDEN 14 antwoorden bekijken Don Genio1 jaar geleden I believe that every single one of those boys would have mentioned Reyes if I could help them get out of trouble, but not one of them ever brought him up! all lies from the cops! 3 BEANTWOORDEN Monica S.1 jaar geleden It’s 2019, you can stop lying now. -

Read, Listen, Watch, ACT BECOMING an ANTI-RACIST EDUCATOR

Read, Listen, Watch, ACT BECOMING AN ANTI-RACIST EDUCATOR “In a racist society, it is not enough to be non-racist, we must be anracist.” --Angela Davis Curated Resources Jusce in June dRworksBook - Home (Dismantling Racism resources) This List Of Books, Films And Podcasts About Racism Is A Start, Not A Panacea Books to read on racism and white privilege in the US Understanding and Dismantling Racism: A Booklist for White Readers People Are Marching Against Racism. They’re Also Reading About It. Books to Read to Educate Yourself About An-Racism and Race An-Racist Allyship Starter Pack Black History Library An-Racism Resource List: quesons, definions, resources, people, & organizaons RESOURCES- -Showing Up for Racial Jusce Read “You want weapons? We’re in a library! Books! Best weapons in the world! This room’s the greatest arsenal we could have. Arm yourself!” ― T he Doctor David Tennant Books and arcles related to anracism (general): A More Perfect Reunion: Race, Integraon, and the Future of America, Calvin Baker Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower, Briany Cooper How to Be an Anracist , Ibram X. Kendi Me and White Supremacy, Layla F. Saad Racism without Racists: Colorblind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva So You Want to Talk about Race , Ijeoma Oluo The New Jim Crow , Michelle Alexander This Book Is An-Racist: 20 Lessons on How to Wake Up, Take Acon, and Do The Work , Tiffany Jewell and Aurelia Durand Waking Up White, White Rage; the Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide , Carol Anderson White Awake: An Honest Look at What It Means to Be White , Daniel Hill hps://blacklivesmaer.com/what-we-believe/ What the data say about police shoongs What the data say about police brutality and racial bias — and which reforms might work Police Violence Calls for Measures Beyond De-escalaon Training Books and arcles related to anracism in educaon: An-Racism Educaon: Theory and Pracce, George J. -

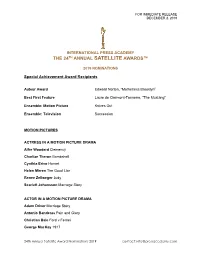

2019 IPA Nomination 24Th Satelilite FINAL 12-2-2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DECEMBER 2, 2019 INTERNATIONAL PRESS ACADEMY THE 24TH ANNUAL SATELLITE AWARDS™ 2019 NOMINATIONS Special Achievement Award Recipients Auteur Award Edward Norton, “Motherless Brooklyn” Best First Feature Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre, “The MustanG” Ensemble: Motion Picture KnIves Out Ensemble: Television Succession MOTION PICTURES ACTRESS IN A MOTION PICTURE DRAMA Alfre Woodard Clemency Charlize Theron Bombshell Cynthia Erivo Harriet Helen Mirren The Good LIar Renee Zellweger Judy Scarlett Johansson MarriaGe Story ACTOR IN A MOTION PICTURE DRAMA Adam Driver MarriaGe Story Antonio Banderas PaIn and Glory Christian Bale Ford v FerrarI George MacKay 1917 24th Annual Satellite Award Nominations 2019 contact: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DECEMBER 2, 2019 Joaquin Phoenix Joker Mark Ruffalo Dark Waters ACTRESS IN A MOTION PICTURE, COMEDY OR MUSICAL Awkwafina The Farewell Ana De Armas KnIves Out Constance Wu Hustlers Julianne Moore GlorIa Bell ACTOR IN A MOTION PICTURE, COMEDY OR MUSICAL Adam Sandler Uncut Gems Daniel Craig KnIves Out Eddie Murphy DolemIte Is My Name Leonardo DiCaprio Once Upon a Time In Hollywood Taron Egerton Rocketman Taika Waititi Jojo RabbIt ACTRESS IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Jennifer Lopez Hustlers Laura Dern MarrIaGe Story Margot Robbie Bombshell Penelope Cruz PaIn and Glory Nicole Kidman Bombshell Zhao Shuzhen The Farewell ACTOR IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Anthony Hopkins The Two Popes Brad Pitt Once Upon a Time In Hollywood Joe Pesci The IrIshman Tom Hanks A BeautIful Day In The NeiGhborhood 24th Annual Satellite Award Nominations 2019 contact: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DECEMBER 2, 2019 Willem Dafoe The LIGhthouse Wendell Pierce BurnInG Cane MOTION PICTURE, DRAMA 1917 UnIversal PIctures Bombshell Lionsgate Burning Cane Array ReleasinG Ford v Ferrari TwentIeth Century Fox Joker Warner Bros. -

Download Download

Katixa Agirre Streaming Minority Languages: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3842-3917 [email protected] The Case of Basque Language Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea Cinema on Netflix Submitted January 9th, 2020 Abstract Approved February 15th, 2021 This article explores the way Basque language cinema is adapting to streaming platforms, focusing on the case of the three Basque language films that have made it to Netflix: Loreak (2014), Handia © 2021 Communication & Society (2017) and Errementari (2018). Firstly, it explains Netflix ISSN 0214-0039 particularities and its emphasis on diversity, among other reasons E ISSN 2386-7876 that could explain the platform’s interest in these particular films. doi: 10.15581/003.34.3.103-115 www.communication-society.com Secondly, it describes the way these aforementioned films have landed on Netflix and the impact this exhibition has had. I base my research on in-depth interviews with directors Jon Garaño and 2021 – Vol. 34(3) pp. 103-115 Paul Urkijo as well as producer Xabi Berzosa to know the insights of the process. More broadly, the article discusses the impact that becoming available on Netflix and other SVOD platforms might How to cite this article: Agirre, K. (2021). Streaming have for Basque cinema, especially when it comes to production Minority Languages: The Case of and transnational distribution. On the other hand, I will also point Basque Language Cinema on at the challenges that this new landscape poses for the Basque Netflix. Communication & Society, 34 (3), 103-115. audiovisual industry, and non-hegemonic languages in general. The streaming revolution, of which Netflix is currently the epitome, is changing the production, distribution, exhibition and consumption model globally, and policy makers and Basque institutions should take this transformation seriously. -

When They See Us Stephen Mccloskey

When They See Us Stephen McCloskey When They See Us (2019) [Television Drama], directed by Ava DuVernay, US: Netflix. For more information visit: https://www.netflix.com/gb/title/80200549 (accessed 1 July 2019). On 19 April 1989, a 28 year-old investment banker, Trisha Meili, went for her regular jog in Central Park at 9.00pm. In the course of her run, she was hit over the head, dragged 300 feet, viciously raped and beaten, and left for dead by her assailant. At the same time, around 30 Black and Latino teenagers streamed into the park from East Harlem, five of whom were arrested for the assault on Trisha Meili who, at the time, seemed likely to succumb to her injuries. What followed has become a national scandal; a miscarriage of justice that revealed the New York Police Department and District Attorney’s Office to be guilty of racial profiling and a fundamental disregard for legal and human rights. The five boys - Raymond Santana (14), Kevin Richardson (14), Antron McCray (15), Yusef Salaam (15) and Korey Wise (16) - were catapulted into a nightmarish and brutalising experience at the hands of racist police officers orchestrated by Lead Prosecutor, Linda Fairstein. Rather than prosecuting suspects on the basis of physical evidence, Fairstein immediately decided on the Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review 169 |P a g e boys’ guilt and worked from that premise to secure their convictions at any cost. The arrest, trials, incarceration and, ultimate, exoneration of the five has been recreated in a gripping four-part television drama, When They See Us (Netflix, 2019a), directed by Ava DuVernay, who received an Academy Award nomination for Selma (2015) and went on to make 13th (2016), a documentary about the United States’ (US) judicial system and what it tells us about racial inequality.