The Fall of Former Shu in 925: an Eyewitness Account

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-936) and Later Jin (936-947) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh- Century Sources

Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-936) and Later Jin (936-947) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh- century Sources Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München vorgelegt von Maddalena Barenghi Aus Mailand 2014 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans van Ess Zweitgutachter: Prof. Tiziana Lippiello Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 31.03.2014 ABSTRACT Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-36) and Later Jin (936-47) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh-century Sources Maddalena Barenghi This thesis deals with historical narratives of two of the Northern regimes of the tenth-century Five Dynasties period. By focusing on the history writing project commissioned by the Later Tang (923-936) court, it first aims at questioning how early-tenth-century contemporaries narrated some of the major events as they unfolded after the fall of the Tang (618-907). Second, it shows how both late- tenth-century historiographical agencies and eleventh-century historians perceived and enhanced these historical narratives. Through an analysis of selected cases the thesis attempts to show how, using the same source material, later historians enhanced early-tenth-century narratives in order to tell different stories. The five cases examined offer fertile ground for inquiry into how the different sources dealt with narratives on the rise and fall of the Shatuo Later Tang and Later Jin (936- 947). It will be argued that divergent narrative details are employed both to depict in different ways the characters involved and to establish hierarchies among the historical agents. Table of Contents List of Rulers ............................................................................................................ ii Aknowledgements .................................................................................................. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 310 3rd International Conference on Culture, Education and Economic Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2019) “Pipa in the Period of Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms” in Music Pictures Xiao Wang College of Music Sichuan Normal University Chengdu, China Abstract—This paper tries to analyze the music images of the kingdoms tend to uphold the concept of "keeping the people at five dynasties and Ten Kingdoms through the combination of ease" and "emphasizing agriculture and suppressing military historical facts, from the angle of the music images, and briefly Force", kingdoms were basically at peace, and encouraged and discusses the characteristics of the five dynasties and ten urged farmers to plant mulberry trees and raise silkworms, kingdoms pipa. This paper probes into the scope of application, built and repaired water conservancy, attracted business travel. form, playing method in the image data of five dynasties and ten kingdoms, and the position of pipa in the instrumental music of Later, the leader of the northern regime — Taizu of the five dynasties and ten kingdoms post-Zhou Dynasty led the troops to destroy the Han Dynasty and establish the kingdom, and after the succession of Shizong Keywords—Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms; pipa; music Chai Rong, in the course of his subsequent development, he picture ; "Han Xizai’s Night Banquet Picture"; "Chorus Picture"; perfected the law and economic and political system, and Gile stone carving of the Seven Treasure Pagodas in Shanxi constantly expanded the territory of his rule, China, which had Pingshun Dayun Temple; Wang Jian's tomb of former-Shu been divided for a long time, begun to show a trend of reunification. -

Places of Interest in Chengdu

Places of Interest in Chengdu Here is a brief list of interesting places in Chengdu. You can visit them conveniently by taking a taxi and showing their Chinese name to the driver. All places are also connected by metro and bus routes for you to explore. 1. 熊熊熊+++úúú000 (Xiong Mao Ji Di) Panda Base Cute pandas and beautiful environment. The house at the end has baby pandas. 2. 金金金沙沙沙WWW@@@ (Jin Sha Yi Zhi) Jinsha Site Museum Archaeological site of ancient Shu civilization (∼1000BC), where the gold ornament with sun bird is found. 3. 888uuu (Yong Ling) Yong Royal Tomb Tomb of Wang Jian who founded the kingdom of Former Shu (∼900AD). Inside there is a sculpture of the king and carvings of musicians with high artistic value. 4. \\\+++III堂堂堂 (Du Fu Cao Tang) Du Fu Thatched Cottage Residence of Du Fu, a famous poet who lived in Tang dynasty (∼700AD). Most buildings are rebuilt after Ming dynasty (∼1500AD). The Sichuan Provincial Museum is also nearby. 5. fff¯¯¯``` (Wu Hou Ci) Wu Hou Shrine Shrine of Zhuge Liang, a famous prime minister of the kingdom of Shu (∼200AD). Most buildings are rebuilt after Qing dynasty (∼1600AD). The tomb of Liu Bei who founded the kingdom of Shu is at the same site. The Jinli Folk Street is also nearby. 6. RRR羊羊羊««« (Qing Yang Gong) Green Goat Temple Taoist temple established in Tang dynasty (∼700AD). Most buildings are rebuilt after Qing dynasty (∼1600AD). Inside there is a bronze goat which is said to bring good fortune. Its restaurant serves vegetarian food (following Taoist standards). -

Chinese Language Program Sichuan University

Chinese Language Program Sichuan University As one of the national key universities directly under the State Ministry of Education (MOE) as well as one of the State “211 Project” and 985 Project” universities enjoying privileged construction in the Ninth Five-Year Plan period, the present Sichuan University (SCU) was first incorporated in April, 1994 with Chengdu University of Science and Technology (CUST), then a national key university under the MOE, and then reincorporated again in Sept, 2000 with the West China University of Medical Science (WCUMS), a key university directly under the State Ministry of Health in 2000. The former Sichuan University was one of the earliest institutes of higher learning in China, with a history dating back to Sichuan Zhong-Xi Xuetang (Sichuan Chinese and Western School), established in 1896. The predecessor of CUST is Chengdu Engineering College, set up in 1954 as the result of the nation-wide college and department adjustment. WCUMS originated from the private Huaxi Xiehe University (West China Union University), established in 1910 by five Christian missionary groups from U.S.A., UK and Canada. Over the course of its long history, SCU has acquired a profound cultural background and a solid foundation in its operation. The university motto “The sea is made great by accepting hundreds of rivers”, and university spirit of “rigorousness, diligence, truth-seeking, and innovation” are at the core of SCU’s raison d’etre. At present, Sichuan University is a first class comprehensive research university in Western China. The University has established 30 Colleges, a College of Graduate Studies, a School of Overseas Education and two independent colleges, Jin Cheng and Jin Jiang College. -

The Great Kingdom of Eternal Peace: Buddhist Kingship in Tenth-Century Dali

buddhist kingship in tenth-century dali Asia Major (2019) 3d ser. Vol. 32.1: 87-111 megan bryson The Great Kingdom of Eternal Peace: Buddhist Kingship in Tenth-Century Dali abstract: Tenth-century China’s political instability extended beyond Tang territorial bound- aries to reach the Dali region of what is now Yunnan province. In Dali, the void left by the fallen Nanzhao kingdom (649–903) was filled by a series of short-lived regimes, the longest of which was Da Changhe guo (903–927), or “The Great King- dom of Eternal Peace.” Though studies of the “Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms” omit Changhe, its rulers’ diplomatic strategies, and particularly their representa- tions of Buddhist kingship, aligned with the strategies of contemporaneous regimes. Like their counterparts to the east, Changhe rulers depicted themselves as heirs of the Tang emperors as well as the Buddhist monarchs Liang Wudi and Aªoka. This article uses understudied materials, including a 908 subcommentary to the Scripture for Humane Kings (Renwang jing) only found in Dali, to argue that Changhe belongs in discussions of religion and politics in tenth-century China, and tenth-century East Asia. keywords: Dali, Yunnan, Changhe kingdom, Scripture for Humane Kings, Buddhism, Five Dynas- ties and Ten Kingdoms, tenth century INTRODUCTION tudies of tenth-century East Asia have long recognized the limita- S tions of Ouyang Xiu’s 歐陽修 (1007–1072) “Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms” model, which took the Song dynastic viewpoint. However, scholarship on this time period continues to apply its focus on the re- gional politics that was of interest to the Song court and its officials.1 This has had the effect of erasing the short-lived regimes in modern- day Yunnan from the period’s overall religious, cultural, and political Megan Bryson, Dept. -

A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture

A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture Edited by Antje Richter LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Acknowledgements ix List of Illustrations xi Abbreviations xiii About the Contributors xiv Introduction: The Study of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture 1 Antje Richter PART 1 Material Aspects of Chinese Letter Writing Culture 1 Reconstructing the Postal Relay System of the Han Period 17 Y. Edmund Lien 2 Letters as Calligraphy Exemplars: The Long and Eventful Life of Yan Zhenqing’s (709–785) Imperial Commissioner Liu Letter 53 Amy McNair 3 Chinese Decorated Letter Papers 97 Suzanne E. Wright 4 Material and Symbolic Economies: Letters and Gifts in Early Medieval China 135 Xiaofei Tian PART 2 Contemplating the Genre 5 Letters in the Wen xuan 189 David R. Knechtges 6 Between Letter and Testament: Letters of Familial Admonition in Han and Six Dynasties China 239 Antje Richter For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV vi Contents 7 The Space of Separation: The Early Medieval Tradition of Four-Syllable “Presentation and Response” Poetry 276 Zeb Raft 8 Letters and Memorials in the Early Third Century: The Case of Cao Zhi 307 Robert Joe Cutter 9 Liu Xie’s Institutional Mind: Letters, Administrative Documents, and Political Imagination in Fifth- and Sixth-Century China 331 Pablo Ariel Blitstein 10 Bureaucratic Influences on Letters in Middle Period China: Observations from Manuscript Letters and Literati Discourse 363 Lik Hang Tsui PART 3 Diversity of Content and Style section 1 Informal Letters 11 Private Letter Manuscripts from Early Imperial China 403 Enno Giele 12 Su Shi’s Informal Letters in Literature and Life 475 Ronald Egan 13 The Letter as Artifact of Sentiment and Legal Evidence 508 Janet Theiss 14 Infijinite Variations of Writing and Desire: Love Letters in China and Europe 546 Bonnie S. -

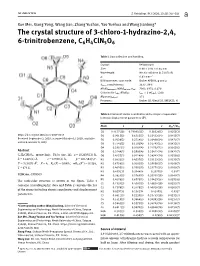

The Crystal Structure of 3-Chloro-1-Hydrazino-2, 4, 6

Z. Kristallogr. NCS 2020; 235(2): 317–318 Xue Mei, Xiang Yong, Wang Jian, Zhang Yushan, Yao Yuehua and Wang Jianlong* The crystal structure of 3-chloro-1-hydrazino-2,4, 6-trinitrobenzene, C6H4ClN5O6 Table 1: Data collection and handling. Crystal: Yellow block Size: 0.08 × 0.06 × 0.04 mm Wavelength: Mo Kα radiation (0.71073 Å) µ: 0.43 mm−1 Diffractometer, scan mode: Bruker APEX-II, φ and ω θmax, completeness: 26.4°, 99% N(hkl)measured, N(hkl)unique, Rint: 7003, 1974, 0.070 Criterion for Iobs, N(hkl)gt: Iobs > 2 σ(Iobs), 1268 N(param)refined: 171 Programs: Bruker [1], Olex2 [2], SHELX [3, 4] Table 2: Fractional atomic coordinates and isotropic or equivalent isotropic displacement parameters (Å2). Atom x y z Uiso*/Ueq Cl1 0.61771(8) 0.79091(15) 0.50526(5) 0.0355(3) https://doi.org/10.1515/ncrs-2019-0647 O1 0.9015(2) 0.6515(5) 0.55432(14) 0.0455(7) Received September 2, 2019; accepted October 17, 2019; available O2 0.9138(2) 0.2714(5) 0.56408(14) 0.0475(7) online November 8, 2019 O3 0.7745(2) −0.1102(4) 0.31743(15) 0.0432(7) O4 0.5901(2) −0.0182(4) 0.22709(13) 0.0365(6) Abstract O5 0.3144(2) 0.5900(4) 0.35412(14) 0.0421(7) C6H4ClN5O6, monoclinic, P21/n (no. 14), a = 10.2139(13) Å, O6 0.4257(2) 0.9114(4) 0.34942(14) 0.0358(6) b = 5.6835(6) Å, c = 17.597(2) Å, β = 106.484(4)°, N1 0.8632(3) 0.4537(5) 0.53113(16) 0.0335(7) 3 2 V = 979.6(2) Å , Z = 4, Rgt(F) = 0.0497, wRref(F ) = 0.1138, N2 0.6758(3) 0.0201(5) 0.29058(17) 0.0308(7) T = 173 K. -

455911 1 En Bookfrontmatter 1..22

Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering 209 Editorial Board Ozgur Akan Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey Paolo Bellavista University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy Jiannong Cao Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Geoffrey Coulson Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK Falko Dressler University of Erlangen, Erlangen, Germany Domenico Ferrari Università Cattolica Piacenza, Piacenza, Italy Mario Gerla UCLA, Los Angeles, USA Hisashi Kobayashi Princeton University, Princeton, USA Sergio Palazzo University of Catania, Catania, Italy Sartaj Sahni University of Florida, Florida, USA Xuemin Sherman Shen University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Canada Mircea Stan University of Virginia, Charlottesville, USA Jia Xiaohua City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong Albert Y. Zomaya University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/8197 Qianbin Chen • Weixiao Meng Liqiang Zhao (Eds.) Communications and Networking 11th EAI International Conference, ChinaCom 2016 Chongqing, China, September 24–26, 2016 Proceedings, Part I 123 Editors Qianbin Chen Liqiang Zhao Post and Telecommunications Xidian University Chongqing University Xi’an Chongqing China China Weixiao Meng Harbin Institute of Technology (HIT) Harbin China ISSN 1867-8211 ISSN 1867-822X (electronic) Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering ISBN 978-3-319-66624-2 ISBN 978-3-319-66625-9 -

The Dreaming Mind and the End of the Ming World

The Dreaming Mind and the End of the Ming World The Dreaming Mind and the End of the Ming World • Lynn A. Struve University of Hawai‘i Press Honolulu © 2019 University of Hawai‘i Press This content is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means that it may be freely downloaded and shared in digital format for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. Commercial uses and the publication of any derivative works require permission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Creative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. The open-access version of this book was made possible in part by an award from the James P. Geiss and Margaret Y. Hsu Foundation. Cover art: Woodblock illustration by Chen Hongshou from the 1639 edition of Story of the Western Wing. Student Zhang lies asleep in an inn, reclining against a bed frame. His anxious dream of Oriole in the wilds, being confronted by a military commander, completely fills the balloon to the right. In memory of Professor Liu Wenying (1939–2005), an open-minded, visionary scholar and open-hearted, generous man Contents Acknowledgments • ix Introduction • 1 Chapter 1 Continuities in the Dream Lives of Ming Intellectuals • 15 Chapter 2 Sources of Special Dream Salience in Late Ming • 81 Chapter 3 Crisis Dreaming • 165 Chapter 4 Dream-Coping in the Aftermath • 199 Epilogue: Beyond the Arc • 243 Works Cited • 259 Glossary-Index • 305 vii Acknowledgments I AM MOST GRATEFUL, as ever, to Diana Wenling Liu, head of the East Asian Col- lection at Indiana University, who, over many years, has never failed to cheerfully, courteously, and diligently respond to my innumerable requests for problematic materials, puzzlements over illegible or unfindable characters, frustrations with dig- ital databases, communications with publishers and repositories in China, etcetera ad infinitum. -

Governing Those Who Live an “Ignoble Existence”: Frontier Administration and the Impact of Native Tribesmen Along the Tang D

Governing those who live an “ignoble existence”: Frontier administration and the impact of native tribesmen along the Tang dynasty’s southwestern frontier, 618-907 A.D. by Cameron R. Stutzman A.S., Johnson & Wales University, 2008 B.A., Colorado State University, 2011 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2018 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. David A. Graff Copyright © Cameron R. Stutzman 2018. Abstract As the Tang dynasty rose to power and expanded into the present-day provinces of Sichuan and Yunnan, an endemic problem of troublesome frontier officials appeared along the border prefectures. Modern scholars have largely embraced Chinese historical scholarship believing that the lawlessness and remoteness of these southwestern border regions bred immoral, corrupt, and violent officials. Such observations fail to understand the southwest as a dynamic region that exposed assigned border officials to manage areas containing hardship, war, and unreceptive aboriginal tribes. Instead, the ability to act as an “effective” official, that is to bring peace domestically and abroad, reflected less the personal characteristics of an official and rather the relationship these officials had with the local native tribes. Evidence suggests that Tang, Tibetan, and Nanzhao hegemony along the southwestern border regions fluctuated according to which state currently possessed the allegiance of the native tribesmen. As protectors and maintainers of the roads, states possessing the allegiance of the local peoples possessed a tactical advantage, resulting in ongoing attacks and raids into the border prefectures by China’s rivals. -

I US-China Transpacific Foundation & Chinese People's Lnsti~Te of Foreign Affairs

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/20/2018 10:07:42 PM I. I US-China Transpacific Foundation & Chinese People's lnsti~te of Foreign Affairs Congressional Staff Delegation to China August2018 Briefing Book - Part t This m·aterial is distribUted by Capitol Counsel LLC on behalf of.U.S.-Chinci Transpacific Foundation. AddJttorial ii:,fonii~ti~I'.' is 8v~_ila_ble a! ,he ~p3rtni¢nt of J_uSt_ice, Washington,. DC. Received by NSD/F ARA Registration Unit 07/20/2018 10:07 :42 PM Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/20/2018 10:07:42 PM. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK This material is distributed. by Capitol C_ounsel LU~ cin behalf of (J_.S.~C_hina Transp_acific Fo~ndBition. Additional information is·available at the Department of Justice. Washington, DC. · Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/20/2018 10:07:42 PM Received by NSDIFARA Registration Unit . 07/20/2018 10:07:42 PM Dnnlllll'llt -----'----------------- Sou~(l'_______________ P,lgl'_ Introduction ltitiera·~ Chinese Pe"0Ple'S·1nstitiit'e ·of FiirE!iPn-Aff.ifrs. -5 Citv Information Wikipedia 7 Preface.Docuinellts __ . _ - -- - - - ·-· The· Siiliiiilill'itv·cif China' Henrv Kissinaer ron Chinal 27 Understandin2 China's Rise Under Xi Jinping The Honorable Kevin Rudd 55 - - -- - . - - -- U.S.-/ Chhta Rtl.itio1islilP - - China vs. America: Man.:il!'iOg the Ne,tt Clash of Civilizations Graham A11ison fForeiRn Affairs l 75 The Crowe Memoranduin He"rii'v Kis·sille:"ei-, fOii. Chiiial . -- - 83 HoW Chiria VieWs-tliC Uiiited·states·an.<1 th-e World. De"ilfl Chell Ii fHeritalie FoundatiOn l 101 The.China Reckonimz: Kurt Campbell & Ely Ratner [Forehm Affairs l 105 - . -

The Price of Orthodoxy: Issues of Legitimacy in the Later Liang and Later Tang*

臺大歷史學報第 35 期 BIBLID1012-8514(2005)35p.55-84 2 0 0 5 年6 月,頁 5 5 ~8 4 2005.5.16 收稿,2005.6.22 通過刊登 The Price of Orthodoxy: Issues of Legitimacy in the Later Liang and Later Tang* Fang, Cheng-hua** Abstract After the decline of the Tang imperial authority in the late ninth century, a number of local warlords competed to erect autonomous regimes by force, gradually establishing their own dynasties. The first two dynasties after the end of the Tang, the Later Liang and the Later Tang, grew out of the rival regimes established by Zhu Wen and Li Keyong. Both Zhu and Li were bellicose generals, but who increasingly came to realize the importance of legitimacy in the process of building their national regimes. To legitimize his power, Zhu Wen claimed that the Tang orthodox authority had been transmitted to him. In contrast, Li Keyong and his son legitimized their fight against Zhu by claiming that they carried the standard of Tang restoration. Although adopting different approaches, both two military-oriented regimes turned to civil issues, such as organizing the bureaucracy and performing rituals. From a cultural perspective, the political leaders’ interest in civil affairs preserved and promoted Confucian tradition under violent conditions. Their claims to orthodoxy before they effectively controlled all of China, however, retarded the military actions of these two regimes, because the attention of their rulers was diverted from the battlefield to civil affairs. This article will analyze the relationship between military expansion and the management of legitimation in both the Later Liang and the Later Tang.