550533-34 Bk Mahler EU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shostakovich (1906-1975)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Born in St. Petersburg. He entered the Petrograd Conservatory at age 13 and studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev and composition with Maximilian Steinberg. His graduation piece, the Symphony No. 1, gave him immediate fame and from there he went on to become the greatest composer during the Soviet Era of Russian history despite serious problems with the political and cultural authorities. He also concertized as a pianist and taught at the Moscow Conservatory. He was a prolific composer whose compositions covered almost all genres from operas, ballets and film scores to works for solo instruments and voice. Symphony No. 1 in F minor, Op. 10 (1923-5) Yuri Ahronovich/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Overture on Russian and Kirghiz Folk Themes) MELODIYA SM 02581-2/MELODIYA ANGEL SR-40192 (1972) (LP) Karel Ancerl/Czech Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Symphony No. 5) SUPRAPHON ANCERL EDITION SU 36992 (2005) (original LP release: SUPRAPHON SUAST 50576) (1964) Vladimir Ashkenazy/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15, Festive Overture, October, The Song of the Forest, 5 Fragments, Funeral-Triumphal Prelude, Novorossiisk Chimes: Excerpts and Chamber Symphony, Op. 110a) DECCA 4758748-2 (12 CDs) (2007) (original CD release: DECCA 425609-2) (1990) Rudolf Barshai/Cologne West German Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1994) ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 6324 (11 CDs) (2003) Rudolf Barshai/Vancouver Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphony No. -

Culture and the Arts Bring Meaning to Our Lives

Culture and the Arts bring meaning to our lives. Culture and the Arts make us the human beings we are and give structure and sense to the society we create; they provide us with real values and fulfil our mental and emotional existence. In the most difficult days of the history of humanity, alongside the most dramatic events, the most devastating wars and epidemics, the Arts, and perhaps especially music, enhanced the spirit. Music became a symbol of resilience, heroism and ultimately our belief in ourselves, from Josef Haydn’s ‘Mass in Time of War’ to Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony. We are at war now and we musicians are desperate to join in in the battle to help society, help people to improve their mental health, fire their spirit and give comfort during this most isolated, most lonely time in our modern history. But we can’t. We are prevented from performing in live spaces, prevented from reaching the eyes and ears and hearts of our public, prevented from sharing with them our love, our passion, our belief. It is becoming more and more apparent that orchestras, opera companies and other musical institutions in the UK, a truly world-leading country in all forms of culture, are in grave danger of being lost forever, if urgent action is not taken. Many of us have had great support through the Job Retention Scheme, and we are really grateful to the Government for that. But we need also to look to the coming months, and even years, and discuss what the impact of this closure, and of contained social distancing remaining, means for the performing arts. -

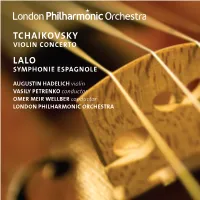

Vasily PETRENKO Conductor

Vasily PETRENKO Conductor Vasily Petrenko was born in 1976 and started his music education at the St Petersburg Capella Boys Music School – the oldest music school in Russia. He then studied at the St Petersburg Conservatoire and has also participated in masterclasses with such major figures as Ilya Musin, Mariss Jansons, and Yuri Temirkanov. Following considerable success in a number of international conducting competitions including the Fourth Prokofiev Conducting Competition in St Petersburg (2003), First Prize in the Shostakovich Choral Conducting Competition in St Petersburg (1997) and First Prize in the Sixth Cadaques International Conducting Competition in Spain, he was appointed Chief Conductor of the St Petersburg State Academic Symphony Orchestra from 2004 to 2007. Petrenko is Chief Conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra (appointed in 2013/14), Chief Conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra (a position he adopted in 2009 as a continuation of his period as Principal Conductor which commenced in 2006), Chief Conductor of the European Union Youth Orchestra (since 2015) and Principal Guest Conductor of the State Academic Symphony Orchestra of Russia (since 2016). Petrenko has also served as Principal Conductor of the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain from 2009-2013, and Principal Guest Conductor of the Mikhailovsky Theatre (formerly the Mussorgsky Memorial Theatre of the St Petersburg State Opera and Ballet) where he began his career as Resident Conductor from 1994 to 1997. Petrenko has worked with many of the world’s most prestigious orchestras including the London Symphony Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Philharmonia, Russian National Orchestra, Orchestre National de France, Czech Philharmonic, Finnish Radio Symphony, NHK Symphony Tokyo and Sydney Symphony. -

An Analytical and Educational Survey of Kenneth Hesketh's Vranjanka

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 5-2008 An Analytical and Educational Survey of Kenneth Hesketh's Vranjanka Alisha Marie Wooley Columbus State University Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Education Commons Recommended Citation Wooley, Alisha Marie, "An Analytical and Educational Survey of Kenneth Hesketh's Vranjanka" (2008). Theses and Dissertations. 14. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/14 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/analyticaleducatOOwool The undersigned, appointed by the Schwob School of Music at Columbus State University, have examined the Graduate Music Project titled AN ANALYTICAL AND EDUCATIONAL SURVEY OF KENNETH HESKETFLS VRANJANKA presented by Alisha Marie Wooley a candidate for the degree of Master of Music in Music Education and hereby certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. Columbus State University AN ANALYTICAL AND EDUCATIONAL SURVEY OF KENNETH HESKETH'S VRANJANKA By Alisha Marie Wooley A MASTERS THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of Columbus State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Education Columbus, Georgia -

RACHMANINOV Piano Concerto No

RACHMANINOV Piano Concerto No. 2 Études-tableaux, Op. 33 Boris Giltburg, Piano Royal Scottish National Orchestra Carlos Miguel Prieto Sergey Rachmaninov (1873–1943): Piano Concerto No. 2 • Études-tableaux, Op. 33 clarinets and hardly the soft violin pizzicatos, as those are been removed, until nothing but a clear and concise Fritz Kreisler (1875–1962): Liebesleid · Franz Behr (1837–1898): Lachtäubchen, ‘Polka de W.R.’ too delicate to carry a long distance. Finally, the clarinets musical idea remains. often can’t hear the pianist clearly, as most of the piano’s Those miniatures were written between August and To play the opening of Rachmaninov’s Second Piano movement (finally the piano gets to play a melody too!) sound also projects into the hall. The resulting danger of September 1911, exactly one year after Rachmaninov Concerto is a singularly powerful experience. You wait for and the slightly exotic second theme of the finale, which this acoustic triangle is that the clarinets and the piano composed the 13 Préludes, Op. 32, thus completing his silence – the piano starts on its own, there’s no need to returns in triumphant splendour at the very end of the may drift apart. It’s a problem which can be solved, but cycle of 24 preludes. Both opuses were composed at maintain eye contact with anyone – and when the hall movement as the ‘point’ of the entire concerto, with a one which we almost always encounter during the first Ivanovka, a country estate some 450 km south-east of seems to have disappeared, you let the first chord sound, huge sound produced by all, a drenched pianist, and the rehearsal. -

Musicweb International August 2020 RETROSPECTIVE SUMMER 2020

RETROSPECTIVE SUMMER 2020 By Brian Wilson The decision to axe the ‘Second Thoughts and Short Reviews’ feature left me with a vast array of part- written reviews, left unfinished after a colleague had got their thoughts online first, with not enough hours in the day to recast a full review in each case. This is an attempt to catch up. Even if in almost every case I find myself largely in agreement with the original review, a brief reminder of something you may have missed, with a slightly different slant, may be useful – and, occasionally, I may be raising a dissenting voice. Index [with page numbers] Malcolm ARNOLD Concerto for Organ and Orchestra – see Arthur BUTTERWORTH Johann Sebastian BACH Concertos for Harpsichord and Strings – Volume 1_BIS [2] Johann Sebastian BACH, Georg Philipp TELEMANN, Carl Philipp Emanuel BACH The Father, the Son and the Godfather_BIS [2] Sir Arnold BAX Morning Song ‘Maytime in Sussex’ – see RUBBRA Amy BEACH Piano Quintet (with ELGAR Piano Quintet)_Hyperion [9] Sir Arthur BLISS Piano Concerto in B-flat – see RUBBRA Benjamin BRITTEN Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings, etc._Alto_Regis [15, 16] Arthur BUTTERWORTH Symphony No.1 (with Ruth GIPPS Symphony No.2, Malcolm ARNOLD Concerto for Organ and Orchestra)_Musical Concepts [16] Paul CORFIELD GODFREY Beren and Lúthien: Epic Scenes from the Silmarillion - Part Two_Prima Facie [17] Sir Edward ELGAR Symphony No.2_Decca [7] - Sea Pictures; Falstaff_Decca [6] - Falstaff; Cockaigne_Sony [7] - Sea Pictures; Alassio_Sony [7] - Violin Sonata (with Ralph VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Violin Sonata; The Lark Ascending)_Chandos [9] - Piano Quintet – see Amy BEACH Gerald FINZI Concerto for Clarinet and Strings – see VAUGHAN WILLIAMS [10] Ruth GIPPS Symphony No.2 – see Arthur BUTTERWORTH Alan GRAY Magnificat and Nunc dimittis in f minor – see STANFORD Modest MUSSORGSKY Pictures from an Exhibition (orch. -

Tchaikovsky Lalo

TCHAIKOVSKY VIOLIN CONCERTO LALO SYMPHONIE ESPAGNOLE AUGUSTIN HADELICH violin VASILY PETRENKO conductor OMER MEIR WELLBER conductor LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA TCHAIKOVSKY VIOLIN coNCErto IN D major If there is a sense of awakening at the start Of the pieces Tchaikovsky and Kotek played of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, it is only through, one that particularly impressed the appropriate. Days before he started composing composer with its ‘freshness’ and ‘musical it in March 1878 he had been picking at a new beauty’ was Édouard Lalo’s new Symphonie piano sonata, with scant success: ‘Am I played espagnole for violin and orchestra. The out?’, he wrote in a letter. ‘I have to squeeze unassuming formal simplicity of Lalo’s out of myself weak and worthless ideas and approach also found its way into Tchaikovsky’s ponder every bar.’ He was writing from the Concerto, though this is not to say that it is house at Clarens near Lake Geneva, where he without craft. The first movement is a sonata was staying as part of his six-month escape form with an elegant introduction and two from Russia following the personal disaster clearly discernible big melodies amid some and mental breakdown provoked by his ill- more fleeting themes, all bound together by considered marriage the previous year. In that subtly glinting thematic connections. ‘Musical period of wandering he had completed both beauty’ is also present; like Mendelssohn in the Fourth Symphony and the opera Eugene his Violin Concerto, Tchaikovsky manages Onegin, but begun very little that was new in effortlessly to make natural partners of lyrical itself. -

Music Catalogue 2021

SUMMARY ELECTRONIC MUSIC p.04 CONTEMPORARY DANCE p.06 JAZZ p.12 OPERA p.14 CLASSICAL p.25 MUSIC DOCUMENTARY p.37 WORLD MUSIC p.40 4K CONCERTS p.42 3 4 The Sonar Festival ZSAMM ISAAC DELUSION LENGTH: LENGTH: 50’ 53’ DIRECTOR: DIRECTOR: SÉBASTIEN BERGÉ ERIC MICHAUD PRODUCER: PRODUCER: Les Films Jack Fébus Les Films Jack Fébus COPRODUCER: COPRODUCER: ARTE France M_Media COPYRIGHT: COPYRIGHT: 2018 2018 Live concert Live concert ARTIST NATIONALITY: ARTIST NATIONALITY: Slovenia, Austria France 27.10.22 07.09.22 Watch the video Watch the video 5 6 Contemporary dance MONUMENTS IN MOTION MONUMENTS IN MOTION SCREWS AND STONES I REMEMBER SAYING GOODBYE LENGTH: LENGTH: 11’ 11’ DIRECTOR: DIRECTOR: GAËTAN CHATAIGNER TOMMY PASCAL PRODUCER: PRODUCER: Les Films Jack Fébus Les Films Jack Fébus COPRODUCERS: COPRODUCERS: Centre des mouve- Centre des mouve- ments nationaux ments nationaux COPYRIGHT: COPYRIGHT: 2020 2019 LANGUAGE AVAILABLE: LANGUAGE AVAILABLE: Live concert Live concert 18.02.29 11.06.24 Watch the video Watch the video Choreography by Alexander Vantournhout Choreography by Christian and François Ben Aïm From the SCREWS performance At the Sainte Chapelle at La Conciergerie de Paris. Performers: Music : Nils Frahm Christien Ben Aïm Dancers : Josse De Broeck, Petra Steindl, Emmi François Ben Aïm Väisänen, Hendrik Van Maele, Alexander Vantournhout, Louis Gillard Felix Zech Piers Faccini (musician) 7 Contemporary dance MONUMENTS IN MOTION 3X10’ SCENA MADRE* LENGTH: LENGTH: 3x10’ 63’ DIRECTOR: DIRECTOR: YOANN GAREL, JULIA GAT, GAËTAN CHATAIGNER THOMAS -

Mardi 3 Octobre Ensemble Intercontemporain Ensemble Inte

Jean-Philippe Billarant, Président du Conseil d’administration Laurent Bayle, Directeur général Mardi 3 octobre Ensemble intercontemporain Dans le cadre du cycle Londres Du mercredi 20 septembre au jeudi 5 octobre 2006 di 3 octobre Mar Vous avez la possibilité de consulter les notes de programme en ligne, 2 jours avant chaque concert, à l’adresse suivante : www.cite-musique.fr Ensemble intercontemporain Ensemble Cycle Londres DU MERCREDI 20 SEPTEMBRE AU JEUDI 5 OCTOBRE Londres : la ville de Purcell, de Haydn, de Britten, mais aussi l’un des berceaux MERCREDI 20 SEPTEMBRE, 20h de la pop, des Beatles à Marianne Faithfull et au-delà. Autour de l’intégrale des douze symphonies dites londoniennes de Haydn, Intégrale des Symphonies un instantané musical de la capitale anglaise, entre humour et solennité, londoniennes I tradition et modernité… Joseph Haydn Nombre de symphonies de Haydn portent des titres imagés, donnés après coup Symphonie no 103 par les chroniqueurs en référence à un motif de l’œuvre ou à un événement Symphonie no 102 qui en a marqué l’exécution. Les symphonies londoniennes ne font pas exception. Symphonie no 104 Toutefois, au-delà des anecdotes qu’elles ont pu susciter, c’est au sein de la grande histoire des formes musicales que ces pages ont laissé leur empreinte. Orchestra of the Age C’est de Londres, où il séjourna de 1791 à 1795, que Haydn rapporta un livret of Enlightenment qui avait d’abord été destiné à Haendel. Ce livret deviendra celui de La Création, Frans Brüggen, direction sans doute son œuvre la plus célèbre. -

Kenneth Hesketh in Ictu Oculi – Orchestral Works

kenneth hesketh in ictu oculi – orchestral works paladino music bbc national orchestra of wales christoph-mathias mueller Kenneth Hesketh (*1968) In Ictu Oculi 01 Knotted Tongues 14:56 02 Of Time and Disillusionment – 1. Fragmented Escapements 03:10 03 Of Time and Disillusionment – 2. Ritornelli 03:10 04 Of Time and Disillusionment – 3. Notturni per i defunti 07:27 05 Of Time and Disillusionment – 4. Corrupted Dances (Geistertänze) 05:04 06 Of Time and Disillusionment – 5. Regulated Escapements 01:49 07 In Ictu Oculi – Three Meditations 19:04 TT 54:42 BBC National Orchestra of Wales Christoph-Mathias Mueller, conductor 2 Knotted Tongues (2012 rev. 2014) Commissioned and premiered by the Seattle Sym- Whence the title? It is a reference to Benson phony Orchestra under Ludovic Morlot, Knotted Bobrick‘s book on the history (often barbaric) and Tongues forms a link in the continuation of a treatment of stammering, the fear of which the latent cycle of works that contemplates the idea author summarises by the memorable phrase “the of the “unreliable machine”, itself based on the anticipation of the glottal catastrophe”. theory of the “beast-machine” by René Descartes (1637) which expounds the idea that the body is no more than a wonderfully complex machine. Most bodies are likely to malfunction, fracture and decay through some self-initiated internal change or mutation, and are, therefore, unreliable. Taking this idea into the musical domain, the formal shape of the work progresses via musical “states” or blocks that rupture, rather than by organic, motivically- related development. The debris of exhausted states forms or allows a subsequent state to arise. -

Recording Master List.Xls

UPDATED 11/20/2019 ENSEMBLE CONDUCTOR YEAR Bartok - Concerto for Orchestra Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop 2009 Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra Rafael Kubelik 1978L BBC National Orchestra of Wales Tadaaki Otaka 2005L Berlin Philharmonic Herbert von Karajan 1965 Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra Ferenc Fricsay 1957 Boston Symphony Orchestra Erich Leinsdorf 1962 Boston Symphony Orchestra Rafael Kubelik 1973 Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa 1995 Boston Symphony Orchestra Serge Koussevitzky 1944 Brussels Belgian Radio & TV Philharmonic OrchestraAlexander Rahbari 1990 Budapest Festival Orchestra Iván Fischer 1996 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Fritz Reiner 1955 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Georg Solti 1981 Chicago Symphony Orchestra James Levine 1991 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Pierre Boulez 1993 Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra Paavo Jarvi 2005 City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Simon Rattle 1994L Cleveland Orchestra Christoph von Dohnányi 1988 Cleveland Orchestra George Szell 1965 Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam Antal Dorati 1983 Detroit Symphony Orchestra Antal Dorati 1983 Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra Tibor Ferenc 1992 Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra Zoltan Kocsis 2004 London Symphony Orchestra Antal Dorati 1962 London Symphony Orchestra Georg Solti 1965 London Symphony Orchestra Gustavo Dudamel 2007 Los Angeles Philharmonic Andre Previn 1988 Los Angeles Philharmonic Esa-Pekka Salonen 1996 Montreal Symphony Orchestra Charles Dutoit 1987 New York Philharmonic Leonard Bernstein 1959 New York Philharmonic Pierre -

In Conversation with a Principal Conductor

In conversation with a Principal Conductor LJMU Roscoe Lecture series welcomes Vasily Petrenko To book a press pass, please contact LJMU Press Officer Clare Coombes on 0151 231 3004 or [email protected] Time: 5.15pm-5.45pm (Event begins at 6pm) Wednesday 14 May 2014 Location: Liverpool Philharmonic Hall I 12 May 2014: Vasily Petrenko, Chief Conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and Liverpool John Moores University Honorary Fellow, will deliver the University’s 119th Roscoe Lecture in conversation with Darren Henley OBE, Managing Director of Classic FM, at Liverpool Philharmonic Hall on 14th May. Vasily Petrenko was appointed Principal Conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra in September 2006; in September 2009 he became Chief Conductor. He is now the Orchestra’s longest serving conductor since Sir Charles Groves, who was principal conductor from 1963 – 1977. He has helped boost audience numbers for concerts by the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and they are now 17% higher than when he first took up the baton. Petrenko received an Honorary Fellowship from LJMU in 2012 for his outstanding contribution to Liverpool and the arts. He has also received Honorary Doctorates from the University of Liverpool and Liverpool Hope University. His other awards include German Echo Klassik Awards 2012 Newcomer of the Year for the recording of Rachmaninov’s Symphony No. 3 with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra (EMI Classics), the Classic BRIT Awards Male Artist of the Year in 2012 and 2010 and the Classic FM/Gramophone Awards Young Artist of the Year 2007. He is also Principal Conductor of the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain, Chief Conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra and Principal Guest Conductor of the Mikhailovsky Theatre in St Petersburg, his native city and where his professional career began in the mid-1990s.