Bois De Boulogne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Vincennes S Ain T-Mand É 16 Et 18, Avenue Aubert Sortie Sortie Bois De Vincennes B Érault Place Du Général Leclerc Fort Neuf a Sortie Venue R De L Av

V incennes Avenue F och Sortie Château-de-Vincennes FONTENAY-SOUS-BOIS Porte de Vincennes S ain t-Mand é 16 et 18, Avenue Aubert Sortie Sortie Bois de Vincennes B érault Place du Général Leclerc Fort Neuf A Sortie venue R de l Av. du Général De Gaulle o a Da u Hôpital Bégin me t Ave Bla e nue de e nche Nogent r d è e i n la i p T GARE 6 é o Aven P ue du u x ROUTIÈRE B u a el- r l A e e i a r l e n l h e CHATEA U d Fontenay-sous-Bois VINCENNES c u DE é e a r u J a n VINCENNES e e M v CHALET DU LAC R t A o r s u t o e e d d P s u r G s r a a l de A r e Lac de S aint-Mandé n venue Fort de Vincennes i d d u M e t s Minim aréc e es o o hal d C b a y e S t a u n s A A o e R e ve e ou v n t t R e de d ue n l n R Ro i 'Esplanad e de o e e n o u N o t t u og F e m e u e u e n d ESPLANADE t e t u L o d d e L R GR 14 A u a te ST-LOUIS e d c ou R u e s n d e C e v g A T A h n S a ve r ê a e n n t i n m A u e E t e v ' - b s l M d e e l a R a n e e s Bois l n y u o l M d e d u u é il in e n t R d a s im e e é e o G e m u s l u d t LA CHESNAIE s a e s a e PARC FLORAL D e d u B e d l DU ROY e a u l e a Jardin botanique de Paris a n Quartier l h l r e la e v T é C A P G o Carnot n y Lac de s Minime s a é u ra e b G r m d r e i a u e VINCENNES l i d c l l d l e R e s . -

Rapport D'activité 2019 Musées D'orsay Et De L'orangerie

Rapport d’activité 2019 Musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie Rapport d’activité 2019 Établissement public des musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie Sommaire Partie 1 Partie 3 Les musées d’Orsay Le public, au cœur de la politique et de l’Orangerie : des collections de l’EPMO 57 exceptionnelles 7 Un musée ouvert à tous 59 La vie des collections 9 L’offre adulte et grand public 59 Les acquisitions 9 L’offre de médiation famille et jeune Le réaccrochage des collections permanentes 9 public individuel 60 Les inventaires 10 L’offre pour les publics spécifiques 63 Le récolement 22 L’éducation artistique et culturelle 64 Les prêts et dépôts 22 Les outils numériques 65 La conservation préventive et la restauration 23 Les sites Internet 65 Le cabinet d’arts graphiques et de photographies 25 Les réseaux sociaux 65 Les accrochages d’arts graphiques Les productions audiovisuelles et numériques 66 et de photographies 25 Le public en 2019 : des visiteurs venus L’activité scientifique 30 en nombre et à fidéliser 69 Bibliothèques et documentations 30 Des records de fréquentation en 2019 69 Le pôle de données patrimoniales digitales 31 Le profil des visiteurs 69 Le projet de Centre de ressources La politique de fidélisation 70 et de recherche 32 Les activités de recherche et la formation des stagiaires 32 Partie 4 Les colloques et journées d’étude 32 L’EPMO, Un établissement tête de réseau : l’EPMO en région 33 un rayonnement croissant 71 Les expositions en région 33 Les partenariats privilégiés 34 Un rayonnement mondial 73 Orsay Grand Département 34 Les expositions -

P22 445 Index

INDEXRUNNING HEAD VERSO PAGES 445 Explanatory or more relevant references (where there are many) are given in bold. Dates are given for all artists and architects. Numbers in italics are picture references. A Aurleder, John (b. 1948) 345 Aalto, Alvar (1898–1976) 273 Automobile Club 212 Abadie, Paul (1812–84) 256 Avenues Abaquesne, Masséot 417 Av. des Champs-Elysées 212 Abbate, Nicolo dell’ (c. 1510–71) 147 Av. Daumesnil 310 Abélard, Pierre 10, 42, 327 Av. Foch 222 Absinthe Drinkers, The (Edgar Degas) 83 Av. Montaigne 222 Académie Française 73 Av. de l’Observatoire 96 Alexander III, Pope 25 Av. Victor-Hugo 222 Allée de Longchamp 357 Allée des Cygnes 135 B Alphand, Jean-Charles 223 Bacon, Francis (1909–92) 270 American Embassy 222 Ballu, Théodore (1817–85) 260 André, Albert (1869–1954) 413 Baltard, Victor (1805–74) 261, 263 Anguier, François (c. 1604–69) 98, Balzac, Honoré de 18, 117, 224, 327, 241, 302 350, 370; (statue ) 108 Anguier, Michel (1614–86) 98, 189 Banque de France 250 Anne of Austria, mother of Louis XIV Barrias, Louis-Ernest (1841–1905) 89, 98, 248 135, 215 Antoine, J.-D. (1771–75) 73 Barry, Mme du 17, 34, 386, 392, 393 Apollinaire, Guillaume (1880–1918) 92 Bartholdi, Auguste (1834–1904) 96, Aquarium du Trocadéro 419 108, 260 Arc de Triomphe 17, 220 Barye, Antoine-Louis (1795–1875) 189 Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel 194 Baselitz, Georg (b. 1938) 273 Arceuil, Aqueduct de 372 Bassin du Combat 320 Archipenko, Alexander (1887–1964) Bassin de la Villette 320 267 Bastien-Lepage, Jules (1848–84) 89, Arènes de Lutèce 60 284 Arlandes, François d’ 103, 351 Bastille 16, 307 Arman, Armand Fernandez Bateau-Lavoir 254 (1928–2005) 270 Batignolles 18, 83, 234 Arp, Hans (Jean: 1886–1966) 269, 341 Baudelaire, Charles 31, 40, 82, 90, 96, Arras, Jean d’ 412 108 Arsenal 308 Baudot, Anatole de (1834–1915) 254 Assemblée Nationale 91 Baudry, F. -

Highlights of a Fascinating City

PARIS HIGHLIGHTS OF A FASCINATING C ITY “Paris is always that monstrous marvel, that amazing assem- blage of activities, of schemes, of thoughts; the city of a hundred thousand tales, the head of the universe.” Balzac’s description is as apt today as it was when he penned it. The city has featured in many songs, it is the atmospheric setting for countless films and novels and the focal point of the French chanson, and for many it will always be the “city of love”. And often it’s love at first sight. Whether you’re sipping a café crème or a glass of wine in a street café in the lively Quartier Latin, taking in the breathtaking pano- ramic view across the city from Sacré-Coeur, enjoying a romantic boat trip on the Seine, taking a relaxed stroll through the Jardin du Luxembourg or appreciating great works of art in the muse- ums – few will be able to resist the charm of the French capital. THE PARIS BOOK invites you on a fascinating journey around the city, revealing its many different facets in superb colour photo- graphs and informative texts. Fold-out panoramic photographs present spectacular views of this metropolis, a major stronghold of culture, intellect and savoir-vivre that has always attracted many artists and scholars, adventurers and those with a zest for life. Page after page, readers will discover new views of the high- lights of the city, which Hemingway called “a moveable feast”. UK£ 20 / US$ 29,95 / € 24,95 ISBN 978-3-95504-264-6 THE PARIS BOOK THE PARIS BOOK 2 THE PARIS BOOK 3 THE PARIS BOOK 4 THE PARIS BOOK 5 THE PARIS BOOK 6 THE PARIS BOOK 7 THE PARIS BOOK 8 THE PARIS BOOK 9 ABOUT THIS BOOK Paris: the City of Light and Love. -

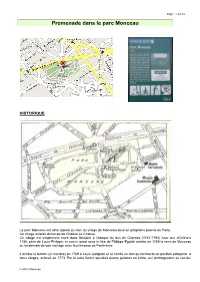

Promenade Dans Le Parc Monceau

Page : 1 sur 16 Promenade dans le parc Monceau HISTORIQUE Le parc Monceau est ainsi appelé du nom du village de Monceau situé en périphérie proche de Paris. Ce village existait du temps de Charles Le Chauve. Ce village est simplement entré dans l’histoire à l’époque du duc de Chartres (1747-1793) futur duc d’Orléans 1785, père de Louis-Philippe, et connu aussi sous le titre de Philippe Egalité achète en 1769 la terre de Monceau au lendemain de son mariage avec la princesse de Penthièvre. Il achète le terrain (un hectare) en 1769 à Louis Colignon et lui confie en tant qu’architecte un pavillon octogonal, à deux étages, achevé en 1773. Par la suite furent ajoutées quatre galeries en étoile, qui prolongeaient au rez-de- Le Parc Monceau Page : 2 sur 16 chaussée quatre des pans, mais l'ensemble garda son unité. Colignon dessine aussi un jardin à la française c’est à dire arrangé de façon régulière et géométrique. Puis, entre 1773 et 1779, le prince décida d’en faire construire un autre plus vaste, dans le goût du jour, celui des jardins «anglo-chinois» qui se multipliaient à la fin du XVIIIe siècle dans la région parisienne notamment à Bagatelle, Ermenonville, au Désert de Retz, à Tivoli, et à Versailles. Le duc confie les plans à Louis Carrogis dit Carmontelle (1717-1806). Ce dernier ingénieur, topographe, écrivain, célèbre peintre et surtout portraitiste et organisateur de fêtes, décide d'aménager un jardin d'un genre nouveau, "réunissant en un seul Jardin tous les temps et tous les lieux ", un jardin pittoresque selon sa propre formule. -

Angkor Redux: Colonial Exhibitions in France

Angkor Redux: Colonial Exhibitions in France Dawn Rooney offers tantalising glimpses of late 19th-early 20th century exhibitions that brought the glory of Angkor to Europe. “I saw it first at the Paris Exhibition of 1931, a pavilion built of concrete treated to look like weathered stone. It was the outstanding feature of the exhibition, and at evening was flood-lit F or many, such as Claudia Parsons, awareness of the with yellow lighting which turned concrete to Angkorian kingdom and its monumental temples came gold (Fig. 1). I had then never heard of Angkor through the International Colonial Exhibitions held in Wat and thought this was just a flight of fancy, France in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries a wonder palace built for the occasion, not a copy of a temple long existent in the jungle of when French colonial presence in the East was at a peak. French Indo-China. Much earlier, the Dutch had secured domination over Indonesia, the Spanish in the Philippines, and the British But within I found photographs and read in India and Burma. France, though, did not become a descriptions that introduced me to the real colonial power in Southeast Asia until the last half of the Angkor and that nest of temples buried with it nineteenth century when it obtained suzerainty over Cam- in the jungle. I became familiar with the reliefs bodia, Vietnam (Cochin China, Tonkin, Annam) and, lastly, and carved motifs that decorated its walls, Laos. Thus, the name ‘French Indochina’ was coined not and that day I formed a vow: Some day . -

Le Paris D'haussmann

56 57 DÉMOLITIONS ET EXPROPRIATIONS le pAris La démolition des quartiers anciens entraîne l’expropriation* d’une partie de la population, qui doit quitter Paris pour s’installer en périphérie. Démolition des habitations Une grande partie de la cité médiévale disparaît du quartier de l’Opéra sous les coups de pioche, tandis que des immeubles afin de réaliser une avenue. aux façades uniformes s’alignent le long d’HAussmAnn des nouveaux boulevards. Poursuivant l’œuvre de ses prédécesseurs, le baron Haussmann, préfet de Paris de 1853 à 1870, modifie radicalement le paysage de la capitale. LES OBJECTIFS Le nouvel empereur, Napoléon III, demande Vue depuis le toit de l’Opéra de Paris Vue depuis le toit de l’Opéra de Paris montrant l’avenue au nouveau préfet, Haussmann, de poursuivre la avant le percement de l’avenue. de l’Opéra et le nouveau quartier aux immeubles bien alignés. modernisation de la ville commencée par Rambuteau. Il faut relier les gares entre elles, créer de larges avenues offrant de belles perspectives sur les monuments et faciliter les déplacements de l’armée en cas d’émeutes. Façade d’un immeuble haussmannien. « Du boulevard du Temple à la barrière du Trône, une entaille ; puis, de ce côté, une autre entaille, de la Madeleine à la plaine Monceau ; et une troisième entaille dans ce sens, une autre dans Caricature du baron Haussmann celui-ci, une entaille là, une entaille plus loin, Sur ce plan le tracé en noir du prolongement en bâtisseur- de la rue de Rivoli vers l’hôtel de ville. des entailles partout. -

LE BOIS DE BOULOGNE Candidature De Paris Pour Les Jeux Olympiques De 2012 Et Plan D’Aménagement Durable Du Bois À L’Horizon 2012

ATELIER PARISIEN D’URBANISME - 17, BD MORLAND – 75004 PARIS – TÉL : 0142712814 – FAX : 0142762405 – http://www.apur.org LE BOIS DE BOULOGNE Candidature de Paris pour les Jeux Olympiques de 2012 et plan d’aménagement durable du bois à l’horizon 2012 Convention 2005 Jeux Olympiques de 2012 l’héritage dans les quartiers du noyau ouest en particulier dans le secteur de la porte d’Auteuil ___ Document février 2005 Le projet de jeux olympiques à Paris en 2012 est fondé sur la localisation aux portes de Paris de deux noyaux de sites de compétition à égale distance du village olympique et laissant le coeur de la capitale libre pour la célébration ; la priorité a par ailleurs été donnée à l'utilisation de sites existants et le nombre de nouveaux sites de compétition permanents a été réduit afin de ne répondre qu'aux besoins clairement identifiés. Le projet comprend : - le noyau Nord, autour du stade de France jusqu’à la porte de la Chapelle ; - le noyau Ouest, autour du bois de Boulogne tout en étant ancré sur les sites sportifs de la porte de Saint Cloud ; - à cela s’ajoutent un nombre limité de sites de compétition « hors noyaux » en région Ile de France et en province, en particulier pour les épreuves de football, ainsi que 2 sites dans le centre de Paris (Tour Eiffel et POPB). Sur chaque site, le projet s’efforce de combiner deux objectifs : permettre aux jeux de se dérouler dans les meilleures conditions pour les sportifs, les visiteurs et les spectateurs ; mais également apporter en héritage le plus de réalisations et d’embellissements pour les sites et leurs habitants. -

Romantic Paris

EXPERT GUIDE ROMANTIC PARIS ACTIVITIES - HOTELS - RESTAURANTS & MORE 2 Table of Contents If you’re wondering how to plan the perfect romantic holiday in Paris, INSIDR has got you covered. This Expert Guide compiles everything we know about seeing Paris through rose-colored lenses. Our Romantic Paris guide will present to you all the reasons why so many artists, poets, and people around the world associate romance with the City of Light. With amazing restaurants, countless romantic spots, and an array of idyllic attractions like the Eiffel Tower and the Moulin Rouge, there are so many ways to experience a memorable romantic time in Paris with your partner. This guide shares the most romantic hotels to stay at, the best Michelin star restaurants to dine at, the most special activities you and your loved-one can’t do anywhere else and of course, our INSIDR Tips! Romantic Activities .................................................................... 3-12 Romantic Accommodation ................................................... 13-15 Romantic Restaurants .............................................................. 16-20 Romantic Bars ............................................................................... 21-23 Sweet Treats ................................................................................... 24 Romantic Day Trips .................................................................... 26-27 Romantic Overnight Stays ...................................................... 27-28 Valentine’s Day in Paris .......................................................... -

Paintings, Photographs, Prints, and Drawings from the Col/Ection of the Art Institute of Chicago, December 9, T989· March T 1990 in Gallery 14

his critical response to the annual» The hie 01 our city is rich In poetiC and marvelous subjects We are enveloped and Sleeped as though If! an Ion exhibition of 1846, french poet Charles atmosphere oj the marvelous, but we do not notice it ,. CH~Rl15 S.~VO[L)IRf ·S,IJ.O~ D( 1&\6' Baudelaire lamented the number of nudes and mythotcgical and historical scenes, which out· numbered paintings that celebrated "the pageant of fashionable life and the thousands of floating existences" of modern Paris. In his view, the quick pace of the city, the bustling of crinolined skirts, and the stop and go of horse-<lrawn om· nibuses were the truths of contemporary life and the onty worthwhile subjects for the modern artist. Whereas in the decade aOer Baudelaire's n oma~ the conet",,, of the pronouncement, the painter's brush may have bicentennial of the french Revolution. been abte to give the impression of urban life, The Art Institute of Chicago has se· the photographer's camera required long expo lected .....orks from its collections of sures, making it difficult to capture the move· Twentieth.(entury Painting. European ment and rich detail of the boulevard parade. It Painting. Photography, Prints and would be two more decades before photography Drawings, and Architecture that cele· could stop the motion of the man on the street. brate france, her land and landmarks. The rising popularity of photographic imagery and her people. The pictures in this was the focus of Baudelaire's famous diatribe of e ~ hib i tion are by artists who .....ere. -

Jean-Charles-Adolphe Alphand Et Le Rayonnement Des Parcs Publics De L’École Française E Du XIX Siècle

Jean-Charles-Adolphe Alphand et le rayonnement des parcs publics de l’école française e du XIX siècle Journée d’étude organisée dans le cadre du bi-centenaire de la naissance de Jean-Charles-Adolphe Alphand par la Direction générale des patrimoines et l’École Du Breuil 22 mars 2017 ISSN : 1967-368X SOMMAIRE Introduction et présentation p. 4 Carine Bernède, directice des espaces verts et de l’environnement de la Ville de Paris « De la science et de l’Art du paysage urbain » dans Les Promenades de Paris (1867-1873), traité de l’art des jardins publics p. 5 Chiara Santini, docteur en histoire (EHESS-Université de Bologne), ingénieur de recherche à l’École nationale supérieure de paysage de Versailles-Marseille Jean-Pierre Barillet-Deschamps, père fondateur d’une nouvelle « école paysagère » p. 13 Luisa Limido, architecte et journaliste, docteur en géographie Édouard André et la diffusion du modèle parisien p. 19 Stéphanie de Courtois, historienne des jardins, enseignante à l’École nationale supérieure d’architecture de Versailles Les Buttes-Chaumont : un parc d’ingénieurs inspirés p. 27 Isabelle Levêque, historienne des jardins et paysagiste Les plantes exotiques des parcs publics du XIXe siècle : enjeux et production aujourd’hui p. 36 Yves-Marie Allain, ingénieur horticole et paysagiste DPLG Le parc de la Tête d’Or à Lyon : 150 ans d’histoire et une gestion adaptée aux attentes des publics actuels p. 43 Daniel Boulens, directeur des Espaces Verts, Ville de Lyon ANNEXES Bibliographie p. 51 -2- Programme de la journée d’étude p. 57 Présentation des intervenants p. -

Mission Relative a La Gestion Des Sites Classes Du Bois De Boulogne Et Du Bois De Vincennes

n° 006777-01 Novembre 2009 MISSION RELATIVE A LA GESTION DES SITES CLASSES DU BOIS DE BOULOGNE ET DU BOIS DE VINCENNES MINISTÈRE DE L’ÉCOLOGIE, DE L’ÉNERGIE, DU DÉVELOPPEMENT DURABLE ET DE LA MER en charge des Technologies vertes et des Négociations sur le climat CONSEIL GÉNÉRAL DE L'ENVIRONNEMENT ET DU DÉVELOPPEMENT DURABLE N° 006777-01 PLAN GENERAL DE LA VILLE DE PARIS COMPRENANT LES BOIS DE BOULOGNE ET DE VINCENNES, SOUS LA DIRECTION D'ALPHAND, 1878 MISSION RELATIVE À LA GESTION DES SITES CLASSÉS DU BOIS DE BOULOGNE ET DU BOIS DE VINCENNES par Michel BRODOVITCH Gilles ROUQUES Inspecteur général Ingénieur général de l'administration du développement durable des ponts, des eaux et des forêts NOVEMBRE 2009 - 1 - RÉSUMÉ La multiplication des projets de constructions et d'installations provisoires dans les Bois de Boulogne et de Vincennes ont amené le ministre chargé des sites a s'interroger sur l'évolution de ces deux sites classés. Le rapport expose la situation des deux bois et présente les actions positives qui y sont menées par la ville de Paris. En tenant compte de la vocation de promenade publique conférée aux deux bois au 19ème siècle, le rapport propose une grille de lecture des projets, complémentaire des principes de gestion de ces sites définis par la Commission supérieure des sites, perspectives et paysages. Cette grille est appliquée à quelques projets en cours. oOo - 2 - MISSION RELATIVE À LA GESTION DES SITES CLASSÉS DU BOIS DE BOULOGNE ET DU BOIS DE VINCENNES SOMMAIRE RÉSUMÉ .................................................................................................................... page 2 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... page 5 1 LES CHARTES D'AMÉNAGEMENT ET LA GOUVERNANCE .........................