Easter 1916 in Poetry and Prose (Dublin)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Fenians: the Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE 8-2014 Making Fenians: The Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876 Timothy Richard Dougherty Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Modern Languages Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dougherty, Timothy Richard, "Making Fenians: The Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876" (2014). Dissertations - ALL. 143. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/143 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the constitutive rhetorical strategies of revolutionary Irish nationalists operating transnationally from 1858-1876. Collectively known as the Fenians, they consisted of the Irish Republican Brotherhood in the United Kingdom and the Fenian Brotherhood in North America. Conceptually grounded in the main schools of Burkean constitutive rhetoric, it examines public and private letters, speeches, Constitutions, Convention Proceedings, published propaganda, and newspaper arguments of the Fenian counterpublic. It argues two main points. First, the separate national constraints imposed by England and the United States necessitated discursive and non- discursive rhetorical responses in each locale that made -

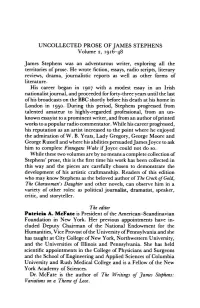

UNCOLLECTED PROSE of JAMES STEPHENS Volume 2, 1916-48

UNCOLLECTED PROSE OF JAMES STEPHENS Volume 2, 1916-48 James Stephens was an adventurous writer, exploring all the territories of prose. He wrote fiction, essays, radio scripts, literary reviews, drama, journalistic reports as well as other forms of literature. His career began in 1907 with a modest essay in an Irish nationalist journal, and proceeded for forty-three years until the last of his broadcasts on the BBC shortly before his death at his home in London in 1950. During this period, Stephens progressed from talented amateur to highly-regarded professional, from an un known essayist to a prominent writer, and from an author of printed works to a popular radio commentator. While his career progi-essed, his reputation as an artist increased to the point where he enjoyed the admiration ofW. B. Yeats, Lady Gregory, George Moore and George Russell and where his abilities persuaded James Joyce to ask him to complete Finnegans Wake if Joyce could not do so. While these two volumes are by no means a complete collection of Stephens' prose, this is the first time his work has been collected in this way and the pieces are carefully chosen to demonstrate the development of his artistic craftmanship. Readers of this edition who may know Stephens as the beloved author of The Crock oJGold, The Charwoman's Daughter and other novels, can observe him in a variety of other roles: as political journalist, dramatist, speaker, critic, and storyteller. The editor Patricia A. McFate is President of the American-Scandinavian Foundation in New York. Her previous appointments have in cluded Deputy Chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, Vice Provost of the University of Pennsylvania and she has taught at City College of New York, Northwestern University, and the Universities of Illinois and Pennsylvania. -

The Great War in Irish Poetry

Durham E-Theses Creation from conict: The Great War in Irish poetry Brearton, Frances Elizabeth How to cite: Brearton, Frances Elizabeth (1998) Creation from conict: The Great War in Irish poetry, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5042/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Creation from Conflict: The Great War in Irish Poetry The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Frances Elizabeth Brearton Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D Department of English Studies University of Durham January 1998 12 HAY 1998 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the impact of the First World War on the imaginations of six poets - W.B. -

![[Jargon Society]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3505/jargon-society-283505.webp)

[Jargon Society]

OCCASIONAL LIST / BOSTON BOOK FAIR / NOV. 13-15, 2009 JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS 790 Madison Ave, Suite 605 New York, New York 10065 Tel 212-988-8042 Fax 212-988-8044 Email: [email protected] Please visit our website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers These and other books will be available in Booth 314. It is advisable to place any orders during the fair by calling us at 610-637-3531. All books and manuscripts are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. 1. ALGREN, Nelson. Somebody in Boots. 8vo, original terracotta cloth, dust jacket. N.Y.: The Vanguard Press, (1935). First edition of Algren’s rare first book which served as the genesis for A Walk on the Wild Side (1956). Signed by Algren on the title page and additionally inscribed by him at a later date (1978) on the front free endpaper: “For Christine and Robert Liska from Nelson Algren June 1978”. Algren has incorporated a drawing of a cat in his inscription. Nelson Ahlgren Abraham was born in Detroit in 1909, and later adopted a modified form of his Swedish grandfather’s name. He grew up in Chicago, and earned a B.A. in Journalism from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in 1931. In 1933, he moved to Texas to find work, and began his literary career living in a derelict gas station. A short story, “So Help Me”, was accepted by Story magazine and led to an advance of $100.00 for his first book. -

SNL05-NLI WINTER 06.Indd

NEWS Number 26: Winter 2006 2006 marked the centenary of the death of the Norwegian poet and playwright Henrik Ibsen. In September, the Library, along with cultural institutions in many countries around the world participated in the international centenary celebration of this hugely influential writer with a number of Ibsen-related events including Portraits of Ibsen, an exhibition of a series of 46 oil paintings by Haakon Gullvaag, one of Norway’s leading contemporary artists, and Writers in Conversation an event held in the Library’s Seminar Room at which RTÉ broadcaster Myles Dungan interviewed the acclaimed Norwegian writer Lars Saabye Christensen. During both September and October, the Library hosted a series of lunchtime readings by the Dublin Lyric Players exploring themes in Ibsen’s writings, and drawing on his Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann poetry and prose as well as his plays. A series of lunchtime lectures looked at Ibsen’s influence on Irish writers and his impact upon aspects of the Irish Revival. National Library of Ireland The Portraits of Ibsen exhibition coincided with the 4-day State Visit to Ireland by Their Majesties King Harald V and Queen Sonja of Norway. On 19 September, Her Majesty Queen Sonja visited the Library to officially open the Portraits of Ibsen NUACHT exhibition, to visit Yeats: the life and works of William Butler Yeats and also to view a number of Ibsen-related exhibits from the Library’s collections; these included The Quintessence of Ibsenism by George Bernard Shaw (1891), Ibsen’s New Drama by James Joyce (1900); Padraic Colum’s copy of the Prose Dramas of Ibsen, given as a gift to WB Yeats, and various playbills for Dublin performances of Ibsen. -

“Am I Not of Those Who Reared / the Banner of Old Ireland High?” Triumphalism, Nationalism and Conflicted Identities in Francis Ledwidge’S War Poetry

Romp /1 “Am I not of those who reared / The banner of old Ireland high?” Triumphalism, nationalism and conflicted identities in Francis Ledwidge’s war poetry. Bachelor Thesis Charlotte Romp Supervisor: dr. R. H. van den Beuken 15 June 2017 Engelse Taal en Cultuur Radboud University Nijmegen Romp /2 Abstract This research will answer the question: in what ways does the poetry written by Francis Ledwidge in the wake of the Easter Rising reflect a changing stance on his role as an Irish soldier in the First World War? Guy Beiner’s notion of triumphalist memory of trauma will be employed in order to analyse this. Ledwidge’s status as a war poet will also be examined by applying Terry Phillips’ definition of war poetry. By remembering the Irish soldiers who decided to fight in the First World War, new light will be shed on a period in Irish history that has hitherto been subjected to national amnesia. This will lead to more complete and inclusive Irish identities. This thesis will argue that Ledwidge’s sentiments with regards to the war changed multiple times during the last year of his life. He is, arguably, an embodiment of the conflicting loyalties and tensions in Ireland at the time of the Easter Rising. Key words: Francis Ledwidge, Easter Rising, First World War, Ireland, Triumphalism, war poetry, loss, homesickness Romp /3 Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Chapter 1 History and Theory ................................................................................................... -

Irish Identity in the Union Army During the American Civil War Brennan Macdonald Virginia Military Institute

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Proceedings of the Ninth Annual MadRush MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference Conference: Best Papers, Spring 2018 “A Country in Their eH arts”: Irish Identity in the Union Army during the American Civil War Brennan MacDonald Virginia Military Institute Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush MacDonald, Brennan, "“A Country in Their eH arts”: Irish Identity in the Union Army during the American Civil War" (2018). MAD- RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference. 1. http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush/2018/civilwar/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 MacDonald BA Virginia Military Institute “A Country in Their Hearts” Irish Identity in the Union Army during the American Civil War 2 Immigrants have played a role in the military history of the United States since its inception. One of the most broadly studied and written on eras of immigrant involvement in American military history is Irish immigrant service in the Union army during the American Civil War. Historians have disputed the exact number of Irish immigrants that donned the Union blue, with Susannah Ural stating nearly 150,000.1 Irish service in the Union army has evoked dozens of books and articles discussing the causes and motivations that inspired these thousands of immigrants to take up arms. In her book, The Harp and the Eagle: Irish American Volunteers and the Union Army, 1861-1865, Susannah Ural attributes Irish and specifically Irish Catholic service to “Dual loyalties to Ireland and America.”2 The notion of dual loyalty is fundamental to understand Irish involvement, but to take a closer look is to understand the true sense of Irish identity during the Civil War and how it manifested itself. -

YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares Beside the Edmund Dulac Memorial Stone to W

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/194 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 3-8, 10-11, 13 Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS AND WOMEN: YEATS ANNUAL No. 9: A Special Number Edited by Deirdre Toomey THAT ACCUSING EYE: YEATS AND HIS IRISH READERS YEATS ANNUAL No. 12: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould and Edna Longley YEATS AND THE NINETIES YEATS ANNUAL No. 14: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS’S COLLABORATIONS YEATS ANNUAL No. 15: A Special Number Edited by Wayne K. Chapman and Warwick Gould POEMS AND CONTEXTS YEATS ANNUAL No. 16: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould INFLUENCE AND CONFLUENCE: YEATS ANNUAL No. 17: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares beside the Edmund Dulac memorial stone to W. B. Yeats. Roquebrune Cemetery, France, 1986. Private Collection. THE LIVING STREAM ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF A. NORMAN JEFFARES YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 A Special Issue Edited by Warwick Gould http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Gould, et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text. -

James Stephens - Poems

Classic Poetry Series James Stephens - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive James Stephens(9 February 1882 - 26 December 1950) James Stephens was an Irish novelist and poet. James Stephens produced many retellings of Irish myths and fairy tales. His retellings are marked by a rare combination of humor and lyricism (Deirdre, and Irish Fairy Tales are often especially praise). He also wrote several original novels (Crock of Gold, Etched in Moonlight, Demi-Gods) based loosely on Irish fairy tales. "Crock of Gold," in particular, achieved enduring popularity and was reprinted frequently throughout the author's lifetime. Stephens began his career as a poet with the tutelage of "Æ" (<a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/george-william-a-e-russell-2/">George William Russel</a>l). His first book of poems, "Insurrections," was published during 1909. His last book, "Kings and the Moon" (1938), was also a volume of verse. During the 1930s, Stephens had some acquaintance with <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/james-joyce/">James Joyce</a>, who found that they shared a birth year (and, Joyce mistakenly believed, a birthday). Joyce, who was concerned with his ability to finish what later became Finnegans Wake, proposed that Stephens assist him, with the authorship credited to JJ & S (James Joyce & Stephens, also a pun for the popular Irish whiskey made by John Jameson & Sons). The plan, however, was never implemented, as Joyce was able to complete the work on his own. During the last decade of his life, Stephens found a new audience through a series of broadcasts on the BBC. -

Austin Clarke Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 83 Austin Clarke Papers (MSS 38,651-38,708) (Accession no. 5615) Correspondence, drafts of poetry, plays and prose, broadcast scripts, notebooks, press cuttings and miscellanea related to Austin Clarke and Joseph Campbell Compiled by Dr Mary Shine Thompson 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 Abbreviations 7 The Papers 7 Austin Clarke 8 I Correspendence 11 I.i Letters to Clarke 12 I.i.1 Names beginning with “A” 12 I.i.1.A General 12 I.i.1.B Abbey Theatre 13 I.i.1.C AE (George Russell) 13 I.i.1.D Andrew Melrose, Publishers 13 I.i.1.E American Irish Foundation 13 I.i.1.F Arena (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.G Ariel (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.H Arts Council of Ireland 14 I.i.2 Names beginning with “B” 14 I.i.2.A General 14 I.i.2.B John Betjeman 15 I.i.2.C Gordon Bottomley 16 I.i.2.D British Broadcasting Corporation 17 I.i.2.E British Council 17 I.i.2.F Hubert and Peggy Butler 17 I.i.3 Names beginning with “C” 17 I.i.3.A General 17 I.i.3.B Cahill and Company 20 I.i.3.C Joseph Campbell 20 I.i.3.D David H. Charles, solicitor 20 I.i.3.E Richard Church 20 I.i.3.F Padraic Colum 21 I.i.3.G Maurice Craig 21 I.i.3.H Curtis Brown, publisher 21 I.i.4 Names beginning with “D” 21 I.i.4.A General 21 I.i.4.B Leslie Daiken 23 I.i.4.C Aodh De Blacam 24 I.i.4.D Decca Record Company 24 I.i.4.E Alan Denson 24 I.i.4.F Dolmen Press 24 I.i.5 Names beginning with “E” 25 I.i.6 Names beginning with “F” 26 I.i.6.A General 26 I.i.6.B Padraic Fallon 28 2 I.i.6.C Robert Farren 28 I.i.6.D Frank Hollings Rare Books 29 I.i.7 Names beginning with “G” 29 I.i.7.A General 29 I.i.7.B George Allen and Unwin 31 I.i.7.C Monk Gibbon 32 I.i.8 Names beginning with “H” 32 I.i.8.A General 32 I.i.8.B Seamus Heaney 35 I.i.8.C John Hewitt 35 I.i.8.D F.R. -

A League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

THE ROLE OF THE GAELIC LEAGUE THOMAS MacDONAGH PATRICK PEARSE EOIN MacNEILL A League of extraordinary gentlemen Gaelic League was breeding ground for rebels, writes Richard McElligott EFLECTING on The Gaelic League was The Gaelic League quickly the rebellion that undoubtedly the formative turned into a powerful mass had given him nationalist organisation in the movement. By revitalising the his first taste of development of the revolutionary Irish language, the League military action, elite of 1916. also began to inspire a deep R Michael Collins With the rapid decline of sense of pride in Irish culture, lamented that the Easter Rising native Irish speakers in the heritage and identity. Its wide was hardly the “appropriate aftermath of the Famine, many and energetic programme of time for memoranda couched sensed the damage would be meetings, dances and festivals in poetic phrases, or actions irreversible unless it was halted injected a new life and colour DOUGLAS HYDE worked out in similar fashion”. immediately. In November 1892, into the often depressing This assessment encapsulates the Gaelic scholar Douglas Hyde monotony of provincial Ireland. the generational gulf between delivered a speech entitled ‘The Another significant factor participation in Gaelic games. cursed their memory”. Pearse the romantic idealism of the Necessity for de-Anglicising for its popularity was its Within 15 years the League had was prominent in the League’s revolutionaries of 1916 and the Ireland’. Hyde pleaded with his cross-gender appeal. The 671 registered branches. successful campaign to get Irish military efficiency of those who fellow countrymen to turn away League actively encouraged Hyde had insisted that the included as a compulsory subject would successfully lead the Irish from the encroaching dominance female participation and one Gaelic League should be strictly in the national school system. -

James Stephens at Colby College

Colby Quarterly Volume 5 Issue 9 March Article 5 March 1961 James Stephens at Colby College Richard Cary. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 5, no.9, March 1961, p.224-253 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Cary.: James Stephens at Colby College 224 Colby Library Quarterly shadow and symbolize death: the ship sailing to the North Pole is the Vehicle of Death, and the captain of the ship is Death himself. Stephens here makes use of traditional motifs. for the purpose of creating a psychological study. These stories are no doubt an attempt at something quite distinct from what actually came to absorb his mind - Irish saga material. It may to my mind be regretted that he did not write more short stories of the same kind as the ones in Etched in Moonlight, the most poignant of which is "Hunger," a starvation story, the tragedy of which is intensified by the lucid, objective style. Unfortunately the scope of this article does not allow a treat ment of the rest of Stephens' work, which I hope to discuss in another essay. I have here dealt with some aspects of the two middle periods of his career, and tried to give significant glimpses of his life in Paris, and his .subsequent years in Dublin. In 1915 he left wartime Paris to return to a revolutionary Dub lin, and in 1925 he left an Ireland suffering from the after effects of the Civil War.