In the Spirit of Harambee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Digital Fundraising in Kenya a Case Study with M-Changa Acknowledgements

Understanding Digital Fundraising in Kenya A Case Study with M-Changa Acknowledgements M-Changa Busara Center for Behavioral Economics Kyai Mullei Nikhil Ravichandar Ben Chege Leah Kiwara Allan Koskei Alessandro Nava Pauline Adisa Gloria Kurere Matt Roberts-Davies James Vancel Benson Njogu Changa Labs Gideon Too Dave Mark Simon Muthusi Dr. Sibel Kusimba Jane Atieno Dave Kim Sarah Swanson Ignacio Mas Caroline Martin Carrie Ngongo Pascal Weinberger African Crowdfunding Association Marina Malkevich Patrick Scofield CGAP FSD Kenya Maria Fernandez Vidal Digital Frontiers Institute ThinkPlace Sheila Kwamboka Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Dean Johnson Carlyn James Aga Khan Foundation Sarah Hassanen Graphics and layout Traci Yoshiyama Table of Contents Introduction 4-5 1 Background 6-8 1.1 Global context 6 1.2 M-Changa history 6 1.3 Methodology and partners 7 1.4 Behavioral biases and 8 fundraising 2 Fundraising & Donations in 9-21 Kenya 2.1 Overview 9 2.2 Locally-relevant research 11 2.3 Why do Kenyans donate? 13 2.3.1 Literature review 13 2.3.2 Findings from our 14 research 2.4 Fundraising trends with 15 M-Changa 2.5 What predicts successful 21 fundraising with M-Changa? 3 Making Fundraising More 22-30 Efficient 3.1 Treatment designs 23 3.1.1 Incentives 25 3.1.2 Anchoring 26 3.1.4 Patrons 27 3.1.5 Top-ups 28 3.2 In summary 29 4 Conclusion - Understanding 31 Digital Charitable Giving in Kenya 5 Appendix 32-46 Understanding Digital Fundraising in Kenya 4 Introduction Introduction Harambee (meaning to ‘all pull together’ in Swahili) is an important aspect of Kenyan culture. -

Kenyan Somali Islamist Radicalisation

Policy Briefing Africa Briefing N°85 Nairobi/Brussels, 25 January 2012 Kenyan Somali Islamist Radicalisation tant government positions. The coalition government has I. OVERVIEW created a ministry to spearhead development in the region. A modest affirmative action policy is opening opportuni- Somalia’s growing Islamist radicalism is spilling over in- ties in higher education and state employment. To most to Kenya. The militant Al-Shabaab movement has built a Somalis this is improvement, if halting, over past neglect. cross-border presence and a clandestine support network But the deployment of troops to Somalia may jeopardise among Muslim populations in the north east and Nairobi much of this modest progress. Al-Shabaab or sympathisers and on the coast, and is trying to radicalise and recruit have launched small but deadly attacks against government youth from these communities, often capitalising on long- and civilian targets in the province; there is credible fear a standing grievances against the central state. This prob- larger terror attack may be tried elsewhere to undermine lem could grow more severe with the October 2011 deci- Kenyan resolve and trigger a security crackdown that could sion by the Kenyan government to intervene directly in drive more Somalis, and perhaps other Muslims, into the Somalia. Radicalisation is a grave threat to Kenya’s securi- movement’s arms. Accordingly, the government should: ty and stability. Formulating and executing sound counter- radicalisation and de-radicalisation policies before it is too recognise that a blanket or draconian crackdown on late must be a priority. It would be a profound mistake, Kenyan Somalis, or Kenyan Muslims in general, would however, to view the challenge solely through a counter- radicalise more individuals and add to the threat of terrorism lens. -

Kenyan Somali Islamist Radicalisation

Policy Briefing Africa Briefing N°85 Nairobi/Brussels, 25 January 2012 Kenyan Somali Islamist Radicalisation tant government positions. The coalition government has I. OVERVIEW created a ministry to spearhead development in the region. A modest affirmative action policy is opening opportuni- Somalia’s growing Islamist radicalism is spilling over in- ties in higher education and state employment. To most to Kenya. The militant Al-Shabaab movement has built a Somalis this is improvement, if halting, over past neglect. cross-border presence and a clandestine support network But the deployment of troops to Somalia may jeopardise among Muslim populations in the north east and Nairobi much of this modest progress. Al-Shabaab or sympathisers and on the coast, and is trying to radicalise and recruit have launched small but deadly attacks against government youth from these communities, often capitalising on long- and civilian targets in the province; there is credible fear a standing grievances against the central state. This prob- larger terror attack may be tried elsewhere to undermine lem could grow more severe with the October 2011 deci- Kenyan resolve and trigger a security crackdown that could sion by the Kenyan government to intervene directly in drive more Somalis, and perhaps other Muslims, into the Somalia. Radicalisation is a grave threat to Kenya’s securi- movement’s arms. Accordingly, the government should: ty and stability. Formulating and executing sound counter- radicalisation and de-radicalisation policies before it is too recognise that a blanket or draconian crackdown on late must be a priority. It would be a profound mistake, Kenyan Somalis, or Kenyan Muslims in general, would however, to view the challenge solely through a counter- radicalise more individuals and add to the threat of terrorism lens. -

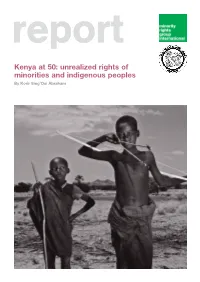

Kenya at 50: Unrealized Rights of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples

report Kenya at 50: unrealized rights of minorities and indigenous peoples By Korir Sing’Oei Abraham Two young Turkana herders near the village of Kache Imeri in Turkana District, northern Kenya. Frederic Courbet / Panos. Acknowledgements also currently represents other minority groups in ongoing This document has been produced with strategic litigation and was a leading actor in the the financial assistance of the European development and drafting of Kenya’s constitutional Union. The contents of this document provisions on minority groups and marginalization. are the sole responsibility of Minority Rights Group International and can Minority Rights Group International under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the Minority Rights Group International (MRG) is a position of the European Union. MRG's local implementation nongovernmental organization (NGO) working to secure the partner is the Ogiek Peoples Development Programme rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and (OPDP). indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation and understanding between communities. Our activities are Commissioning Editor: Beth Walker, Production Coordinator: focused on international advocacy, training, publishing and Jasmin Qureshi, Copy editor: Sophie Richmond, outreach. We are guided by the needs expressed by our Typesetter: Kavita Graphics. worldwide partner network of organizations, which represent minority and indigenous peoples. The Author Korir Sing’Oei Abraham is a co-founder of the Centre for MRG works with over 150 organizations in nearly 50 Minority Rights Development. He is a human rights attorney countries. Our governing Council, which meets twice a year, and an advocate of the High Court of Kenya. For more than has members from 10 different countries. -

ANNUAL REPORT & Financial Statements 2010-2011

ANNUAL REPORT & Financial Statements 2010-2011 © KHRC 2011 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Message from the Chair 6 Foreword 7 .0. Introduction to Report 0 .. About the KHRC 0 .2. Context of the Year 0 .3. Introduction 2 2.0. Annual Report 4 2.. Building Social Movements 4 2.2. People’s Manifesto and Scorecard Initiative 7 2.3. Regional Advocacy Initiatives 2 2.4. Monitoring, Documenting and Responding to Human Rights Violations 23 2.5. Constitutional Reform 25 2.6. Transitional Justice 26 2.7. Business, Trade and Human Rights 29 2.8. Communication, Media and Publicity 3 2.9. Equality and Anti-Discrimination Campaign 33 2.0. Kenya Human Rights Institute 34 2.. Sustainability and Programme Effectiveness 34 3.0. Thank You 36 Winning Team 37 Financial Statements 38 • Kenya Human Rights Commission Pamoja Tutetee Haki 2 LisT of Abbreviations 0-20 ALPS Accountability, Learning and Planning System CADL Comprehensive Anti Discrimination Law CBO Community Based Organisation CDF Constituency Development Fund CDF Constituency Development Funds CIC Commission for the Implementation of the Constitution CIOC Constitutional Implementation Oversight Committee CoE Committee of Experts CRECO Constitution and Reform Education Consortium EPAs Economic Partnership Agreements FBOs Faith Based Organisations FCO Foreign and Commonwealth Office FIDA-Kenya Federation of Women Lawyers, Kenya GoK Government of Kenya HRDs Human Rights Defenders HURINETs Human Rights Networks Annual Report and Financial Statements 20 ICC International Criminal Court ICJ-Kenya -

KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis

REPUBLIC OF KENYA KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis Published by the Government of Kenya supported by United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) P.O. Box 48994 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-271-1600/01 Fax: +254-20-271-6058 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ncpd-ke.org United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce P.O. Box 30218 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-76244023/01/04 Fax: +254-20-7624422 Website: http://kenya.unfpa.org © NCPD July 2013 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors. Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used inconjunction with commercial purposes or for prot. KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS JULY 2013 KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS i ii KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................iv FOREWORD ..........................................................................................................................................ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..........................................................................................................................x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................xi -

Directory of Public Elementary and Secondary Education Agencies, 2000-2001

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 472 649 EA 032 306 AUTHOR McDowell, Lena M.; Sietsema, John P. TITLE Directory of Public Elementary and Secondary Education Agencies, 2000-2001. INSTITUTION National Center for Education Statistics (ED), Washington, DC. REPORT NO NCES-2003-310 PUB DATE 2002-11-00 NOTE 410p.; For the 1999-2000 Directory, see ED 464 396. AVAILABLE FROM ED Pubs, P.O. Box 1398, Jessup, MD 20794-1398. Tel: 877 -433- 7827 (Toll Free). For full text: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2003/2003310.pdf. PUB TYPE Numerical/Quantitative Data (110) Reference Materials Directories /Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Elementary Secondary Education; Enrollment; Government Publications; *Public Agencies; *Public Schools; *School Districts; School Personnel; School Statistics; State Departments of Education IDENTIFIERS Grade Span Configuration ABSTRACT This directory lists all public elementary and secondary education agencies in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, five outlying areas, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the Department of Defense, as reported from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Common Core of Data (CCD) Local Education Agency Universe data collection of spring 2001. In the introduction, several tables summarizing the file contents are provided. The seven types of agencies listed include regular school districts, supervisory union components, supervisory union administrative centers, regional educational service agencies, state-operated agencies, federally operated agencies, and other agencies that cannot be appropriately classified using another CCD designation. The directory provides up to 12 items of information for each public elementary and secondary agency listed: state, name of agency, mailing address, telephone number, name of county, metropolitan status code, grade span, total student membership, number of regular high school graduates for the 1999-2000 school year, number of students with an individualized education program (IEP), number of teachers, and number of schools. -

"DO DOGS APE?" OR "DO APES DOG?" and DOES Rr MATTER? BROADENING and DEEPENING COGNITIVE ETHOLOGY

"DO DOGS APE?" OR "DO APES DOG?" AND DOES rr MATTER? BROADENING AND DEEPENING COGNITIVE ETHOLOGY By MA~c BEKOFF4' "Certainlyit seems like a dirty double-cross to enter into a relationshipof trust and affection with any creaturethat can enter into such a relationship, and then to be a party to'its premeditated and premature destruction."1 I. RAiN WrrHouT TmmDER, ANimAS Wrrour MINDS In Rain Without Thunder, Gary Francione raises numerous impor- tant issues and takes on many important people.2 The phrase "rain with- out thunder" made me think about the notion of animals without minds- animals without thoughts or feelings. This idea is troublesome for the nonhuman animals (hereafter animals) to whom it is attributed because it is much easier for humans to exploit animals when we believe that they don't have thoughts or feelings. I have been privileged to study various aspects of animal behavior for over 25 years, including animal cognition3 (cognitive ethology), and have attempted to learn more about how the study of animal cognition can aid discussions of animal protection. 4 As a * Professor of Biology, University of Colorado, Boulder;, A.B. and PILD., Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri; Guggenheim Fellow and Fellow of the Animal Behavior Soci- ety; Correspondence: Marc Bekoff, 296 Canyonside Drive, Boulder, Colorado 80302; Emaih [email protected] 1 LAWRENCE E. JoHNsoN, A MORALLY DEEP WoRLD: AN E.sxe*ON MORAL SIGNIFICANCE AND ENvmonwNAL ETmcs 122 (1991). 2 GARY L. FPNtcioNE, RAiN WmoUr TnuDER TIE IDEOLOGY OF mm.EAn,,AL RPiurrs MovmiErr (1996). 3 INTERPRrrATION AND EXPLANATION IN T-E STUDY OF Amm- Bcsxion (Marc Bekoff & Dale Jamieson eds., 1990); READINGS 1N AmAL COGNMON (Marc Bekoff & Dale Jamieson eds., 1996); Marc Bekoff & Colin Allen, Cognitive Ethology: Slayers, Skeptics, and Propo- nents, in ANmRoPoiORPmS.e ANscDoTE, ANzmms: TuE EMpERiO's NEW CLOTnts? 313 (Rob- ert W. -

The Diplomatic Gaffe That Could Sour Relations Between Kenya and Somalia,Why Directive on SGR Cargo Could Kill Kenya's Small T

Trump, Ukraine, and the Whistleblower: Why Reporting Wrongdoing Remains a Perilous Activity By Rasna Warah “I think we will not understand what is happening in our society until we listen to the tears, the screams, the pain, and horror of those who have crossed a boundary they did not even know exists. To be a whistleblower is to step outside the Great Chain of Being, to join not just another religion, but another world. Sometimes this other world is called the margins of society, but to the whistleblower it feels like outer space.” – C. Fred Alford, Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power (2001). President Donald Trump’s thinly veiled attacks against the anonymous whistleblower who reported his shady dealings with the President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky, have once again highlighted what a dangerous activity whistleblowing can be. The US president is reported to have stated: “I want to know who’s the person who gave the whistleblower the information because that’s close to a spy. You know what we used to do in the old days when we were smart? Right? With spies and treason, right? We used to handle them a little differently than we do now.” By equating whistleblowing with treason, Trump is doing exactly what many people in power do when confronted with a revelation that shows them in a bad light – they shoot the messenger by accusing him of being disloyal – a traitor – or of having damaged an organisation’s reputation. For this, the whistleblower is either fired, ridiculed or psychologically tortured. (In the case of Trump, he would prefer that the Ukraine scandal whistleblower be hanged.) What most people don’t understand is that no one wakes up one day and decides to blow the whistle on their employer. -

Assessing the Impact of Kenya's Trade and Investment Policies and Agreements on Human Rights - 5 the Republic of Kenya: Key Facts

In cooperation with the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OR HUMAN RIGHTS? Assessing the Impact of Kenya’s Trade and Investment Policies and Agreements on Human Rights International Fact-Finding Mission Article 1 : All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one ano- ther in a spirit of brotherhood. Article 2 : Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or terri- tory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or un- der any other limitation of sovereignty. n°506a October 2008 2 Table of contents I. Introducing the Mission........................................................................................................4 Map of Kenya.........................................................................................................................5 The Republic of Kenya: Key Facts........................................................................................6 II. The Human Rights Framework..........................................................................................7 1. Identification of duty holders.............................................................................................7 -

Kenya National Human Rights Book 2011 EDITED2

THE THIRD ST THE THIRD STATE OF In the world of Human Rights Protection and enforcement, there are few issues as important as monitoring and accountability, hence a report such as this plays a crucial function in providing a snapshot- a bird’s eye view - HUMAN RIGHTS A of the state of human rights in Kenya in 2010. TE OF HUMAN RIGHTS REPOR REPORT Prof. J Oloka-Onyango, Director of the Human Rights & Peace Centre (HURIPEC) and former Dean of Law at Makerere University, Uganda. It is laudable that this report devotes significant attention to economic and social rights. In Kenya public and policy discussions on access to electricity, water, education, food, health and housing are still not sufficiently linked to T - the discourse on human rights. KNCHR will have made an important A Human Rights Assessment of contribution to the promotion of human rights in Kenya if it succeeds in reshaping the discussions on these rights. Dr. Willy Mutunga Senior Counsel, Regional Representative, Eastern Africa Office, A HUMAN RIGHTS ASSESSMENT Ford Foundation. OF KENYA VISION 2030 K January 2008 - June 2010 eny a V ision 2030 Published by Kenya National Commission on Human Rights Ist Floor, CVS Plaza, Lenana Road P. O. Box 74359 - 00200, Nairobi Kenya Tel: +254 020 2717900/08 Fax: +254 020 271616 Email: [email protected] © Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, 2011 The Third State of Human Rights Report A Human Rights Assessment of Kenya Vision 2030 Published by Kenya National Commission on Human Rights P.O. Box 74359 - 00200 Nairobi Kenya. © Kenya National commission on Human Rights, 2011 Excerpts from this report may be reproduced, provided that there is an acknowledgement to the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights THE THIRD STATE OF HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT AA HumanHuman RightsRights AssessmentAssessment OfOf KenyaKenya VisionVision 20302030 JanuaryJanuary 20082008 -- JuneJune 20102010 Kenya National Commission on Human Rights The Third State of Human Rights Report FOREWORD The KNCHR is to be commended for producing its Third State of Human Rights Report. -

Collegian 2007 04 25.Pdf (15.00Mb)

College avenue hits raCks today! THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN Fort Collins, Colorado COLLEGIAN Volume 115 | No. 149 wednesday, april 25, 2007 www.collegian.com THE STUDENT VOICE OF COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1891 the LIMELIGHT GOING VetHOME delivers mercy By Brandon lowrey contacts The Rocky Mountain Collegian • For grief counselors at the Argus In stitute at the CSU Veterinary Teaching Hospital: LOVELAND — Joni O’Neill runs a hand (970) 217-7069 along her black Labrador’s coat. • Home to Heaven: (970) 412-6212 Jonah, lying down on a mat in the O’Neill family’s country-style home, answers excit- edly by wagging his tail. And if dogs grin, he’s grinning. sic. Her dark blue Toyota van fills with silence, His tongue shoots out to score a few quick and the silence fills with focus. kisses on O’Neill’s face. She manages to smile. She’s not religious, but she prays — a rem- But for a few moments too long, Jonah’s nant of her Catholic upbringing. old eyes stare up into hers. O’Neill finally Let it be a peaceful passing. Let everything looks away as tears and a stifled sob betray go well. her feelings. “It’s almost like a superstitious thing, This is how she wants it to end. now,” she says. “I wanted to put him down with a smile on Cooney recently performed her his face,” she said. “I put one down suffering 103rd euthanasia — about 30 procedures in before, and...” April, alone — unthinkable if she felt guilty, She trails off. even for a moment.