Castle Bytham Colour.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Groundwater in Jurassic Carbonates

Groundwater in Jurassic carbonates Field Excursion to the Lincolnshire Limestone: Karst development, source protection and landscape history 25 June 2015 Tim Atkinson (University College London) with contributions from Andrew Farrant (British Geological Survey) Introduction 1 The Lincolnshire Limestone is an important regional aquifer. Pumping stations at Bourne and other locations along the eastern edge of the Fens supply water to a large population in South Lincolnshire. Karst permeability development and rapid groundwater flow raise issues of groundwater source protection, one of themes of this excursion. A second theme concerns the influence of landscape development on the present hydrogeology. Glacial erosion during the Middle Pleistocene re-oriented river patterns and changed the aquifer’s boundary conditions. Some elements of the modern groundwater flow pattern may be controlled by karstic permeability inherited from pre-glacial conditions, whereas other flow directions are a response to the aquifer’s current boundary conditions. Extremely high permeability is an important feature in part of the confined zone of the present-day aquifer and the processes that may have produced this are a third theme of the excursion. The sites to be visited will demonstrate the rapid groundwater flow paths that have been proved by water tracing, whereas the topography and landscape history will be illustrated by views during a circular tour from the aquifer outcrop to the edge of the Fenland basin and back. Quarry exposures will be used to show the karstification of the limestone, both at outcrop and beneath a cover of mudrock. Geology and Topography The Middle Jurassic Lincolnshire Limestone attains 30 m thickness in the area between Colsterworth and Bourne and dips very gently eastwards. -

Danelaw Way 5 Castle Bytham to Stamford.Pdf

Section 5 Castle Bytham to Stamford Section 5 Castle Bytham to Stamford ______________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________ CASTLE BYTHAM to STAMFORD (Via Tolethorpe, Ryhall and Belmesthorpe) Route Description: (12½ miles) Commencing the walk from outside the Castle Inn turn LEFT up 22 Church Lane, passing church on left. Continue ahead past old school Walk Outline: (1907), then LEFT in front of the cemetery entrance to follow path around cemetery. At the corner pass through the kissing gate then RIGHT over This final section has a dramatic walk high above the Holywell Quarry disused railway bridge. At the next gate two waymarks point in similar followed by a route through Pickworth Great Wood, reputed to be the quietest directions to the left. A few yards beyond the path divides. Take the LEFT fork place in all England and then across John Clare country along The Drift, an old (initially straight ahead) and maintain a southerly direction then south/south drove road. Our reconnaissance groups could not agree which was the best east to arrive at a finger post on the roadside at gap in hedge. Cross over the route into Stamford and therefore we decided to publish both routes, one via road to another finger post to continue direction down to the field bottom, Ryhall and Belmsthorpe and the other direct to Stamford from Tolethorpe. then up the slope to pass dilapidated farm buildings left, shown on map as Whichever route you choose it will be a fitting end to a magnificent School Farm. Ahead to power post with waymark then FORWARD to cross recreational walk through some wonderful countryside. -

Callconnect 4 Stamford-Grantham Callconnect 4 Stamford-Grantham

CallConnect 4 Stamford-Grantham Mondays to Fridays (from 19 July 2021) service no. 4 4 4 4 4 4 notes NSch Sch Stamford, Bus Station Bay 1 0835 1135 1305 1505 1505 1725 Stamford, Morrisons Car Park 0841 1141 1311 1511 - 1731 Stamford, Rutland Road 0844 1144 1314 1514 - 1734 Stamford, Peterhouse Close - - - - 1510 - Ryhall, Coppice Road 0849 1149 1319 1519 1518 1739 Essendine, Village Hall - - - - 1521 - Carlby, High Street - - - - 1523 - Careby, Station Road 0856 1156 1326 1526 1531 1746 Holywell, Home Farm House 0859 1159 1329 1529 1534 1749 Castle Bytham, Castle Inn 0907 1207 1337 1537 1543 1757 Little Bytham, The Mallard 0915 1215 1345 1545 1551 1805 Creeton, Counthorpe Road 0919 1219 1349 1549 1555 1809 Swinstead, Croake Hill 0923 1223 1353 1553 1559 1813 Corby Glen, Fighting Cocks Inn 0927 1227 1357 1557 1603 1817 Burton le Coggles, Demand Responsive Area 0932a1232a - - - 1822a Bitchfield, The Crown 0936 1236 - - - 1826 Boothby Pagnell, Letter Box 0941 1241 - - - 1831 Old Somerby, Fox & Hounds 0945 1245 - - - 1835 Grantham, Prince William Barracks 0949 1249 - - - 1839 Grantham, Bus Station Stand 6 0955 1255 - - - 1845 Swayfield, Demand Responsive Area - - 1402a1602a1608a - Explanation of notes: NSch this journey runs during school holidays only Sch this journey runs on schooldays only a all journeys to or from these points must be prebooked at least two hours before travelling on 0345 234 3344 CallConnect 4 Stamford-Grantham Saturdays (from 19 July 2021) service no. 4 4 4 4 notes Stamford, Bus Station Bay 1 0905 1105 1235 1535 - Stamford, -

TRADES L>IRECTORY. Baicplrs Continued

TRADES l>IRECTORY. 325 BAicPlRs continued. Lowe E. Sibsey, Boston Quincey J. Stanbow lane, Boston Harrison T. & Son, West street, Boston Lowe J. Billinghay, Sleaford Quipp J. Market place, Brig~ Harrison G. Far street, Horncastle Lowe J. Morton, Bourn Quipp R. 261 High street, Lmcoln Harri!!on T. Tetford, Horncastle Lowe W. Billinghay, Sleaford Ranby W. Donington, Spalding Harrison W. Spilsby Loweth J. All Saints' street, Stamford Rastall T. Swineshead, Spalding Harrison William, Princess street, 16 Lowther J. 16 Melville street, & Norman Ray R. Mablethorpe, Alford Bailgate, & Burton road, Lincoln street, Lincoln Rayner H. Kirton end, Kirton, Boston Heaton W. Bridge street, Horncastle Lunn W. Welton, Lincoln Read 1\Iiss M. A. High street, .Boston Henson T. Uffington, Stamford Lynn T. 13 Strait, Lincoln ReedJ. Billingborough, Falkingham HibbertThomas,36&37 8incilst.Lincoln Mager C. Firsby, Spilsby Reeson R. Kirton, Boston Hickman J. Long Sutton Major Mrs. F. Mesl!ingham, Kirton-in- Revell W. Hacconby, Bourn Higgins W. Albert street, Spalding Lindsey Rhoades J. Orby, Spilsby Hill Mrs. A.South Ormsby-cum-Ketsby, Marriott J. W estlode street, Spalding Richards J. Whaplode drove, Crowland Alford Mat'Shall J. Market f.lace, Horncastle Richards J. North street, Stamford Hill E. Epworth Martin H. East Kea, Spilsby Rippon E. Donington, Stalding Hill J. Reform street, Crowland ~Iartin W. Butterwick, Boston Robinson J. 30 Steep bil, Lincoln HillS.Herringbdg. Pinchbeck,Spalding Matthews J. A. Trusthorpe, Alford Robson T. Lincoln lane, Boston Hill W. Pointon, Folkingham Mawer John, Partney, Spilsby Rogers W. Bassingbam, Newark HirdS. Bardney, Wraghy Meniman G. Churchgate, Spalding RolfeJ. High street, Boston Hobson J. -

C. Public Transport Information (Map and Timetable Information)

C. Public Transport Information (Map and Timetable Information) Proposed Development Site, Bridge End, Colsterworth Project Number: CIV15366-100 Document Reference: 001 – v.2 Final K:\Projects\CIV15366 - 100 Main St Colsterworth\Reports\CIV15366-100-001 - v.2 - Final Transport Statement Report.doc Lincolnshire Cty Map Side_Lincolnshire M&G 31/03/2014 15:23 Page 1 A Scunthorpe B C HF to Hull D GRIMSBY Grimsby E Cleethorpes FG Scunthorpe Brocklesby 3 HF 9811 HF Cleethorpes 100.101 Keelby 100 161 Brigg HF 103.161 HF HF 3.21.25 101 28.50.51 103 Brigg HF Laceby 50 NORTH 21 NORTH Great 28 Grasby Limber 3 Irby LINCOLNSHIRE 161 51 1 Messingham 9811 Swallow NORTH EAST 1 103 161 161 3 LINCOLNSHIRE Holton 25 le Clay Cherry Park Information correct to September 2013 Caistor 51 Hibaldstow North Kelsey Cabourne 50 50 Scotter Tetney 161 Grainsby North Cotes Kirton in Lindsey 161 Nettleton Marshchapel 161 25 East Ferry 100 9811 Moortown Rothwell East North 38 Croxby Ravendale Thoresby 50 101 Scotton Kirton in South 3 Lindsey Kelsey 21 Laughton 161 38 Grainthorpe North 11A Thorganby 28 Fulstow Somercotes 0 12 3 4 5 miles Waddingham Holton-le-Moor 51 Grayingham Brookenby 38 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 kilometres East Ludborough 50 Blyton 103 38 Stockwith Snitterby Claxby Binbrook 38.50 96/97 to Retford 100 161 Utterby Saltfleet 101 Willoughton 161 25 398 to Belton Bishop Osgodby 3 3X see Gainsborough Norton Morton Town Map for details Tealby Kirmond 3X 2 in this area Le Mire Fotherby 21 Corringham 11A 3L.3X 3X 28 Alvingham Saltfleetby 95.95A Hemswell Hemswell 3 9 106 9811 161 3X 25 51 51M 96/97 Cliff Glentham PC23 161 1 398 GAINSBOROUGH 28 2 West Middle 51M 1 28 Central MARKET RASEN 3L 1.9 1 Rasen Rasen 3L 3X 3X see Louth Town Map 9 51M 106 Glentworth Bishopsbridge for details in this area Theddlethorpe Ludford 38 Lea Road Market North 25 LOUTH Grimoldby St. -

})Ost OFFIC~ Ti~Colnslttlt

})oSt OFFIC~ ti~COLNslttlt HuTcH:Ims~tintied. Walton G. 'S\Vinegate, Grantbam Bray H. East street, Horncastlt\ Smith T. New road, Spalding Wand C. Castlegate, Grantharn Brown John, Victoria street west, Gft\at Smith W. Braceborough, Stamford Wand R. Commercial road, Grtmtham Grimsby Sneath 0. Westgate, Grantham Wand W. Watergate, Grantbam Burtchby J. Crowle Snowden R. Eastgate, Louth Wand W. j u n. Little Gonerby, G:nl.n tham Butters J. East street, 1Io'l.'nc'astle Southwell W. A. York street, Boston Ward R. W elby street, Grantpam Button J. CaiStor Spa.fford J. tJaypole, Newark Warner E. Kirton, Boston. Button Thomas, Spring gardehs, 'Gam~- Sparrow G. Glentham, Market Rnsen Warwick G. Market street, Barton-on- borough Speed R. Fiskerton, Lincoln Humber Clark J. Rosegarth street, Bostcm Spencer T. Osboumby, Falkingham Warwick G. M. West street, Ci'owland Clark W. Crescent gardens, Spaldiug Spencer W. M~therin~aih Waterfield W. W. St. Peter's street, Colam William,jun. Lee street, Louth Spratt J. High street, Homeastle Stamford Collings T. Bridge street, Gain~ borough Squier W. Falkingham Watmough W. Ilaxey Copeland E. Heckington, Sleaford Squire W. Pinchbeck, Spalding Watson & Son, Caistor Copping T. C. High etreet, 8palding Squires J. Long Bennington, Gratitham Watson D. Laceby, Great Grimsby Coulam W. H. Eastgate, .Louth Stainthorpe J. Bull ring, Horncnstle Watson D. Moulton, Holbeach Cowling J. Crowle Stan~ell A. Market strtJet,., Gainsboro' Watson T. Tallington> Stamford Cranwell B. St. Peter's bill, Granthttm Stanewell W. Epworth Webster J. Walkergate, Louth Darlow A. South street, New Sleaford Stanton J. Castle Bytham., Stamford Wedd A. -

Lawnwood, Bottleneck and Jackson's

wood consisting mainly of oak and ash, with field maple, OS: 130 • GR: SK 993 193 • 12.2ha midland hawthorn and the (30.20 acres) • Freehold 1993 scarce wild service tree. The Habitat type: Woodland/Meadows ground flora includes species The reserve is situated north-east of of old woodland, such as wood Castle Bytham and is reached from an anemone, woodruff and early- unclassified road (Counthorpe Lane) purple orchid. Fallow and red linking Castle Bytham and Creeton. deer are frequently to be seen Limited parking is available on the verge in the wood and meadows. near a bend in the road. Please do not The meadows are sometimes cut for obstruct the farm track with vehicles. hay in July, and the aftermath is grazed Follow the track on foot about 250 m to by sheep or cattle. In the wood, the entrance. The entrance (GR: SK 996 thinning operations are designed to 193) is through a gate or stile. restore a varied ground flora. Parts are coppiced, while the ride system has been extended to provide edge habitat The meadows were given to the Trust in for birds and butterflies. The boundary 1993 by Mrs Mary Harris as a memorial between the wood and the meadows to her husband, David Harris. Lawn provides particularly important habitat, Wood was purchased in 1995. which is being carefully looked after in order to retain and extend the scrubby The reserve consists of two meaows, margins. named Bottleneck and Jackson’s Paddock, and the adjoining Lawn Wood. The name Bottleneck aptly describes the shape of the first field, which lies to the north-west of Lawn Wood. -

183 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

183 bus time schedule & line map 183 Corby Glen View In Website Mode The 183 bus line (Corby Glen) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Corby Glen: 2:25 PM - 4:40 PM (2) Great Casterton: 7:20 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 183 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 183 bus arriving. Direction: Corby Glen 183 bus Time Schedule 34 stops Corby Glen Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 2:25 PM - 4:40 PM Monday 2:25 PM - 4:40 PM Morrison Car Park, Stamford Tuesday 2:25 PM - 4:40 PM Stamford & Rutland Hospital, Stamford Wednesday 2:25 PM - 4:40 PM Stamford College, Stamford Thursday 2:25 PM - 4:40 PM Stamford Free Church, Stamford Friday 2:25 PM - 4:40 PM 169 Kesteven Road, Stamford Saturday 2:25 PM - 4:40 PM Green Lane, Stamford Welland Academy, Stamford Selwyn Road, Stamford 183 bus Info Direction: Corby Glen Charles Road, Stamford Stops: 34 Trip Duration: 66 min Charles Road, Stamford Line Summary: Morrison Car Park, Stamford, Trinity Road, Stamford Stamford & Rutland Hospital, Stamford, Stamford College, Stamford, Stamford Free Church, Stamford, 169 Kesteven Road, Stamford, Welland Academy, Lambeth Walk, Stamford Stamford, Selwyn Road, Stamford, Charles Road, Lambeth Walk, Stamford Stamford, Trinity Road, Stamford, Lambeth Walk, Stamford, Radcliffe Road, Stamford, Beverley Radcliffe Road, Stamford Gardens, Stamford, Waverley Gardens, Stamford, Caledonian Road, Stamford, Ayr Close, Stamford, Beverley Gardens, Stamford Belvoir Close, Stamford, Arran Road (North End), Casterton Road, -

Mapping the Cult of St James the Great in England During the Middle Ages: from the Second Half of the 11Th Century Until the Middle of the 14Th Century1

MARTA AMEIJEIRAS BARROS Mapping the cult of St James the Great in England… Mapping the cult of St James the Great in England during the Middle Ages: from the second half of the 11th century until the middle of the 14th century1 Marta Ameijeiras Barros The University of Edinburgh Trazando el culto de Santiago el Mayor en Inglaterra durante la Edad Media: desde mediados del siglo XI hasta mediados del siglo XIV Resumen: Este estudio es el resultado de la investigación del impacto que el culto a Santiago el Mayor y la peregrinación a Compostela tuvieron en el paisaje arquitectónico de Inglaterra durante la Edad Media y la relación de las dedicaciones jacobeas inglesas con las vías de comunicación existentes en aquel momento. La cronología en la que se enmarca este trabajo, de la segunda mitad del siglo XI a me- diados del siglo XIV, no significa una acotación exacta, ya que se han tenido en cuenta las fundaciones jacobeas del período anterior, y las fechas de muchos de los edificios estudiados resultan confusas. Los principales objetivos de esta investigación son demostrar de una manera visual la existencia de una devoción compostelana consolidada ya desde época temprana y, además, servir como herramienta que ayude a visualizar los posibles itinerarios de los peregrinos jacobeos a través de la Inglaterra medieval. Palabras clave: Santiago el Mayor, arquitectura, dedicaciones, Inglaterra, Edad Media, mapa, rutas de peregrinaje. 1 This paper is based on a section of my current PhD dissertation at the University of Edinburgh under the supervision of Dr Heather Pulliam and Prof Manuel Castiñeiras. -

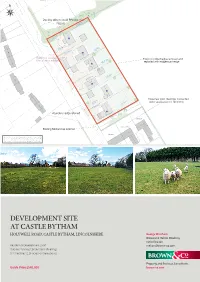

Development Site at Castle Bytham

43 N 45 T4 Bytham Quarry site In-principle support for residential development: S14/3097 S T A T I O N R O A D D The Corner House, consented under B Y T H A M R O A applications ref:S11/3071 & S14/0168 L I T T L E The Old Rectory The Corner House Russet Place H O L Y W E L L The Rectory R O A D 2 R O A + D T3 + T2 + + C L I P S H A M Dwelling siting to avoid RPA (see tree Report) + 23.0 m + T1 + 4.74 m 1 12 + 3 16.5 m 18.8m 16 21.8 m Visibility in excess of 2.4m x Existing conifer hedge removed and 43m at each entrance point replaced with indigenous hedge R E G A L 16.7 m 2 G A R D E N S 25.8m 16 1 6 Three new build dwellings consented under application ref: S00/0537 20.0m 5 10 24 27.9 m 13.6 m T4 Boundary hedge retained G3 T5 Oakhouse 9 Churchfield House 14 Existing field access retained Pine View This Plan is based upon the Ordnance Survey Map with the sanction of the Controller of H.M. Stationery Office. Crown Copyright reserved. (ES100005264). This Plan is published for the convenience of Purchasers only. Its accuracy is not guaranteed and it is expressly excluded from any contract. NOT TO SCALE. 15 H O L Y W E L L R O A Glebe Cottage 9 The Barns D B Y T H A M H E I G H T S 15 Rosewell Shiatsu Centre 21 19 DEVELOPMENT SITE 30mph speed limit AT CASTLE BYTHAM 25 HOLYWELL ROAD, CASTLE BYTHAM, LINCOLNSHIRE George Watchorn Brown&Co Melton Mowbray 01664 502120 Residential Development Land [email protected] Outline Planning Consent for 6 dwellings 0.47 hectares (1.16 acres) or thereabouts Property and Business Consultants Guide Price £540,000 brown-co.com LOCATION METHOD OF SALE The land is situated to the south-east of Castle Bytham. -

TRANSPORT 2020 Route Finder Stamford College Transport Guide Stamford College Transport Guide Route Finder

Stamford College TRANSPORT 2020 Route Finder Stamford College Transport Guide Stamford College Transport Guide Route Finder Lower Benefield ..............................................1 Thorney ...............................................................4 ROUTE FINDER Manton ................................................................ 8 Thurlby ..............................................................PS Market Deeping .........................................PS Tickencote ....................................................... 14 Market Overton ........................................... 14 Tinwell .................................................................. 8 Ailsworth ............................................................4 Dunsby .............................................................PS Maxey ..................................................................12 Toft .......................................................................PS Alwalton ...............................................................3 Easton on the Hill ...........................................1 Moulton ............................................................. 10 Uffington .........................................................PS Apethorpe ...........................................................1 Edith Weston................................................... 8 Moulton Chapel ............................................12 Upper Benefield .............................................1 Aslackby ...........................................................PS -

1G Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

1G bus time schedule & line map 1G Grantham View In Website Mode The 1G bus line (Grantham) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Grantham: 7:25 AM - 6:25 PM (2) Little Bytham: 8:00 AM - 6:00 PM (3) Lobthorpe: 9:00 AM (4) South Witham: 7:00 AM - 3:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 1G bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 1G bus arriving. Direction: Grantham 1G bus Time Schedule 54 stops Grantham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:25 AM - 6:25 PM Demand Responsive Area, Little Bytham Tuesday 7:25 AM - 6:25 PM Demand Responsive Area, Castle Bytham Wednesday 7:25 AM - 6:25 PM Demand Responsive Area, Creeton Thursday 7:25 AM - 6:25 PM Demand Responsive Area, Swinstead Friday 7:25 AM - 6:25 PM Croake Hill, Swinstead Civil Parish Saturday 7:30 AM - 5:25 PM Demand Responsive Area, South Witham Demand Responsive Area, Lobthorpe Demand Responsive Area, Swayƒeld 1G bus Info High Street, Swayƒeld Civil Parish Direction: Grantham Stops: 54 Demand Responsive Area, Corby Glen Trip Duration: 237 min Laxton Lane, Corby Glen Civil Parish Line Summary: Demand Responsive Area, Little Bytham, Demand Responsive Area, Castle Bytham, Demand Responsive Area, Irnham Demand Responsive Area, Creeton, Demand Responsive Area, Swinstead, Demand Responsive Demand Responsive Area, Folkingham Area, South Witham, Demand Responsive Area, Lobthorpe, Demand Responsive Area, Swayƒeld, Chapel Lane, Folkingham Civil Parish Demand Responsive Area, Corby Glen, Demand Demand Responsive Area, Walcot