The Language of Exile: Language and Memory In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turkmen of Iraq

Turkmen of Iraq By Mofak Salman Kerkuklu 1 Mofak Salman Kerkuklu Turkmen of Iraq Dublin –Ireland- 2007 2 The Author Mofak Salman Kerkuklu graduated in England with a BSc Honours in Electrical and Electronic Engineering from Oxford Brookes University and completed MSc’s in both Medical Electronic and Physics at London University and a MSc in Computing Science and Information Technology at South Bank University. He is also a qualified Charter Engineer from the Institution of Engineers of Ireland. Mr. Mofak Salman is an author of a book “ Brief History of Iraqi Turkmen”. He is the Turkmeneli Party representative for both Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom. He has written a large number of articles that were published in various newspapers. 3 Purpose and Scope This book was written with two clear objectives. Firstly, to make an assessment of the current position of Turkmen in Iraq, and secondly, to draw the world’s attention to the situation of the Turkmen. This book would not have been written without the support of Turkmen all over the world. I wish to reveal to the world the political situation and suffering of the Iraqi Turkmen under the Iraqi regime, and to expose Iraqi Kurdish bandits and reveal their premeditated plan to change the demography of the Turkmen-populated area. I would like to dedicate this book to every Turkmen who has been detained in Iraqi prisons; to Turkmen who died under torture in Iraqi prisons; to all Turkmen whose sons and daughters were executed by the Iraqi regime; to all Turkmen who fought and died without seeing a free Turkmen homeland; and to the Turkmen City of Kerkuk, which is a bastion of cultural and political life for the Turkmen resisting the Kurdish occupation. -

Soft Power Or Illusion of Hegemony: the Case of the Turkish Soap Opera “Colonialism”

International Journal of Communication 7 (2013), 2361-2385 1932–8036/20130005 Soft Power or Illusion of Hegemony: The Case of the Turkish Soap Opera “Colonialism” ZAFER YÖRÜK PANTELIS VATIKIOTIS Izmir University of Economics The article develops two simultaneous arguments; one is theoretical, and the other is analytic. The theoretical argument is based on an assessment of the utility of the concept of “soft power” in comparison to the Gramscian concept of hegemony in understanding the developments in the recent regional power games in the geographical area consisting of Eastern Europe and the near and Middle East. The analytic argument examines the popularity of Turkish soap operas, both among a cross-cultural audience and within the wider context of cultural, economic, and political influences, and in so doing, it points out challenges and limits for Turkey’s regional power. Introduction This article notes the recent boom in the popularity of Turkish soap operas in the Middle East, the Balkans, and some (predominantly “Turkic”) former Soviet Republics in Asia, and examines the discourse of Turkish “soft power” that has developed upon this cultural development. The research focuses here on the analysis of two case studies—of the Middle East and Greece— where the Turkish series are very popular. Both cases are able to contribute different perspectives and explanations of this “cultural penetration” across both sides of a geographical area containing Eastern Europe and the near and Middle East, evaluating Turkey’s “influence” accordingly.1 1 In this regard, the limits of the analysis of the present study are set. Although a general framework of the perception of the Turkish series is provided along both case studies (popularity; aspirations and identifications), further research is needed in order to provide a detailed account of the impact of Turkish series on the related societies. -

A Rhetorical History of the British Constitution of Israel, 1917-1948

A RHETORICAL HISTORY OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION OF ISRAEL, 1917-1948 by BENJAMIN ROSWELL BATES (Under the Direction of Celeste Condit) ABSTRACT The Arab-Israeli conflict has long been presented as eternal and irresolvable. A rhetorical history argues that the standard narrative can be challenged by considering it a series of rhetorical problems. These rhetorical problems can be reconstructed by drawing on primary sources as well as publicly presented texts. A methodology for doing rhetorical history that draws on Michael Calvin McGee's fragmentation thesis is offered. Four theoretical concepts (the archive, institutional intent, peripheral text, and center text) are articulated. British Colonial Office archives, London Times coverage, and British Parliamentary debates are used to interpret four publicly presented rhetorical acts. In 1915-7, Britain issued the Balfour Declaration and the McMahon-Hussein correspondence. Although these documents are treated as promises in the standard narrative, they are ambiguous declarations. As ambiguous documents, these texts offer opportunities for constitutive readings as well as limiting interpretations. In 1922, the Mandate for Palestine was issued to correct this vagueness. Rather than treating the Mandate as a response to the debate between realist foreign policy and self-determination, Winston Churchill used epideictic rhetoric to foreclose a policy discussion in favor of a vote on Britain's honour. As such, the Mandate did not account for Wilsonian drives in the post-War international sphere. After Arab riots and boycotts highlighted this problem, a commission was appointed to investigate new policy approaches. In the White Paper of 1939, a rhetoric of investigation limited Britain's consideration of possible policies. -

Middle East Brief 9

Brandeis University Crown Center for Middle East Studies Mailstop 010 Waltham, Massachusetts 02454-9110 781-736-5320 781-736-5324 Fax www.brandeis.edu/centers/crown/ Middle East Brief Are Former Enemies Becoming Allies? Turkey’s Changing Relations with Syria, Iran, and Israel Since the 2003 Iraqi War Dr. Banu Eligr Turkey’s relations with Syria and Iran were strained for almost two decades. This was primarily because both countries had supported the Kurdish separatist terrorist organization the PKK (the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, also known as Kongra- Gel) since the organization launched its war against Turkey in 1984. But these relations have completely changed in the aftermath of the 2003 Iraqi war. Turkey has been enhancing its ties with Syria and Iran, at a time when the United States has been trying to isolate those countries. This has occurred because Turkey, Syria, and Iran are all concerned about potential Iraqi territorial disintegration in the future, which might produce a Kurdish state in the North. This, in turn, might lead to irredentist claims on the Kurdish-populated sectors of all three countries, which would threaten their territorial integrity. Since the Iraqi war, the PKK, after renouncing a unilateral cease-fire in the summer of 2004, has resumed its terrorist attacks in Turkey; 1,007 Turkish citizens have been killed or wounded as a result of terrorist attacks.1 In August 2005, the PKK also launched a campaign of violence in Syria and Iran.2 Because of the continued presence of the PKK in the American-controlled region of northern Iraq and the mistreatment of Turkmens in Telafer and Kirkuk, Turkey has been deeply questioning the extent to which the United States can continue to be considered a trustworthy ally.3 Anti-Americanism is on the rise August 2006 in Turkey. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ILL-FATED’ SONS OF THE ‘NATION’: OTTOMAN PRISONERS OF WAR IN RUSSIA AND EGYPT, 1914-1922 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Yucel Yarukdag. -

Abigail Jacobson, Ph.D. Contact Information

Abigail Jacobson Abigail Jacobson, Ph.D. Contact Information: 49 Green Street #4 Brookline MA 02446 USA Email: [email protected] Education Ph.D., 2006 Department of History, the University of Chicago, Title of Dissertation: From Empire to Empire: Jerusalem in the Transition between Ottoman and British Rule, 1912-1920. Ph.D. Supervisors: Rashid Khalidi, Holly Shissler, Leora Auslander M.A., 2000 (Cum Laude) Department of Middle Eastern and African History, Tel Aviv University B.A., 1997 Department of Middle Eastern and African History, Sociology (double major), Tel Aviv University Academic Employment 2012-2014 Lecturer, Department of History, MIT Fall 2013 Lecturer, Department of History, Boston University Fall 2012 Visiting Research Fellow, Elie Wiesel Center for Judaic Studies, Boston University 2011-2012 Junior Research Fellow, The Crown Center for Middle East Studies, Brandeis University 2010-2011 Lecturer, NYU-Tel Aviv Program 2010 Lecturer, Summer School in Comparative Conflict Studies, Belgrade, Serbia 2006-2011 Lecturer, Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Israel, School for Government and International Program (RRIS) 2007-2008 Post-Doctoral Fellow, Tel Aviv University 2006-2008 Lecturer, Department of Middle Eastern and African History, Tel Aviv University 1999- 2000 Teaching assistant, Department of Middle Eastern and African History, Tel Aviv University 1 Abigail Jacobson Publications Books From Empire to Empire: Jerusalem between Ottoman and British Rule (Syracuse University Press, 2011). Advanced Contract Jews from Middle Eastern Countries and Jewish-Arab Relations in Mandatory Palestine (provisional title), co-authored with Tammy Razi and Moshe Naor (University Press of New England) Peer-Review Articles “When a City Changes Hands: Jerusalem in the Transition between Ottoman and British Rule,” Zmanim (Forthcoming, 2014) “American "Welfare Politics": American Involvement in Jerusalem During World War I,” Israel Studies, Vol. -

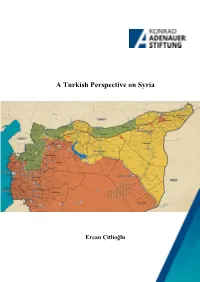

A Turkish Perspective on Syria

A Turkish Perspective on Syria Ercan Çitlioğlu Introduction The war is not over, but the overall military victory of the Assad forces in the Syrian conflict — securing the control of the two-thirds of the country by the Summer of 2020 — has meant a shift of attention on part of the regime onto areas controlled by the SDF/PYD and the resurfacing of a number of issues that had been temporarily taken off the agenda for various reasons. Diverging aims, visions and priorities of the key actors to the Syrian conflict (Russia, Turkey, Iran and the US) is making it increasingly difficult to find a common ground and the ongoing disagreements and rivalries over the post-conflict reconstruction of the country is indicative of new difficulties and disagreements. The Syrian regime’s priority seems to be a quick military resolution to Idlib which has emerged as the final stronghold of the armed opposition and jihadist groups and to then use that victory and boosted morale to move into areas controlled by the SDF/PYD with backing from Iran and Russia. While the east of the Euphrates controlled by the SDF/PYD has political significance with relation to the territorial integrity of the country, it also carries significant economic potential for the future viability of Syria in holding arable land, water and oil reserves. Seen in this context, the deal between the Delta Crescent Energy and the PYD which has extended the US-PYD relations from military collaboration onto oil exploitation can be regarded both as a pre-emptive move against a potential military operation by the Syrian regime in the region and a strategic shift toward reaching a political settlement with the SDF. -

The Iraqi Turkmen (1921-2005)

THE IRAQI TURKMEN (1921-2005) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by A. Gökhan KAYILI In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA August 2005 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. Asst. Prof. Nur Bilge Criss Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. Asst. Prof. Türel Yılmaz Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. Asst. Prof. Hasan Ünal Examining Committee Member Approval of the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT THE IRAQI TURKMEN (1921-2005) Kayılı, A.Gökhan M.I.R, Department of International Relations Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Nur Bilge Criss August 2005 This thesis evaluates the situation of the Iraqi Turkmen between 1921-2005 in terms of the important developments in Iraq. The Iraqi Turkmen could not organize politically due to the oppressive Iraqi regimes in the period between 1921-1991. They started to carry out political activities openly after the Gulf War II in Northern Iraq. The Turkmen who are the third largest ethnic population in Iraq, pursue the policy of keeping the integrity of Iraqi territory, enjoying the same equal rights as the other ethnic groups and being a founding member in the constitution. -

Secularism and Foreign Policy in Turkey New Elections, Troubling Trends

Secularism and Foreign Policy in Turkey New Elections, Troubling Trends Soner Cagaptay Policy Focus #67 | April 2007 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2007 by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy Published in 2007 in the United States of America by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050, Washington, DC 20036. Design by Daniel Kohan, Sensical Design and Communication Front cover: Turkish prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinezhad speak through a translator during a meeting in Tehran, December 3, 2006. The photos above them depict the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and current Supreme Leader Ali Hossein Khamenei. Copyright AP Wide World Photos/Vahid Salemi. About the Author Soner Cagaptay is a senior fellow and director of The Washington Institute’s Turkish Research Program. His extensive writings on U.S.-Turkish relations and related issues have appeared in numerous scholarly journals and major international print media, including Middle East Quarterly, Middle Eastern Studies, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Reuters, Guardian, Der Spiegel, and La Stampa. He also appears regularly on Fox News, CNN, NPR, Voice of America, al-Jazeera, BBC, CNN-Turk, and al-Hurra. His most recent book is Islam, Secularism, and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who Is a Turk? (Routledge, 2006). A historian by training, Dr. -

The U.S.-Turkey-Israel Triangle

ANALYSIS PAPER Number 34, October 2014 THE U.S.-TURKEY-ISRAEL TRIANGLE Dan Arbell The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined by any donation. Copyright © 2014 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 www.brookings.edu Acknowledgements I would like to thank Haim and Cheryl Saban for their support of this re- search. I also wish to thank Tamara Cofman Wittes for her encouragement and interest in this subject, Dan Byman for shepherding this process and for his continuous sound advice and feedback, and Stephanie Dahle for her ef- forts to move this manuscript through the publication process. Thank you to Martin Indyk for his guidance, Dan Granot and Clara Schein- mann for their assistance, and a special thanks to Michael Oren, a mentor and friend, for his strong support. Last, but not least, I would like to thank my wife Sarit; without her love and support, this project would not have been possible. The U.S.-Turkey-Israel Triangle The Center for Middle East Policy at BROOKINGS ii About the Author Dan Arbell is a nonresident senior fellow with Israel’s negotiating team with Syria (1993-1996), the Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings, and later as deputy chief of mission at the Israeli and a scholar-in-residence with the department of Embassy in Tokyo, Japan (2001-2005). -

French Postcolonial Nationalism and Afro-French Subjectivities

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 9-2011 French Postcolonial Nationalism and Afro-French Subjectivities Yasser A. Munif University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Munif, Yasser A., "French Postcolonial Nationalism and Afro-French Subjectivities" (2011). Open Access Dissertations. 479. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/479 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! FRENCH POSTCOLONIAL NATIONALISM AND AFRO-FRENCH SUBJECTIVITIES A Dissertation Presented by YASSER A. MUNIF Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SEPTEMBER 2011 SOCIOLOGY ! ! ! © Copyright by Yasser A. Munif 2011 All Rights Reserved ! ! ! FRENCH POSTCOLONIAL NATIONALISM AND AFRO-FRENCH SUBJECTIVITIES A Dissertation Presented by YASSER A. MUNIF Approved as to style and content by: __________________________________________ Agustin Lao-Montes, Chair __________________________________________ Joya Misra, Member __________________________________________ Millie Thayer, Member -

Media-Watch-On-Hate-Speech-May

Media Watch on Hate Speech & Discriminatory Discourse May - August 2014 Report Hrant Dink Foundation Halaskargazi Cad. Sebat Apt. No. 74 D. 1 Osmanbey-Şişli 34371 İstanbul/TÜRKİYE Tel: 0212 240 33 61 Faks: 0212 240 33 94 E-posta: [email protected] www.hrantdink.org www.nefretsoylemi.org Media Watch on Hate Speech Project Team İrem Az Nuran Gelişli Rojdit Barak Zeynep Arslan Part I: Hate Speech in National and Local Press in Turkey İdil Engindeniz Şahan Part II: Discriminatory Discourse in Print Media Rita Ender Translator Bürkem Cevher Media Watch on Hate Speech Project is funded by Friedrich Naumann Foundation, Global Dialogue and MyMedia/Niras. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders. CONTENTS MONITORING HATE SPEECH IN THE MEDIA 1 MONITORING HATE SPEECH IN THE NATIONAL AND LOCAL PRESS IN TURKEY 2 PART I: HATE SPEECH IN PRINT MEDIA 6 FINDINGS 7 NEWS ITEMS SELECTED DURING THE MAY – AUGUST 2014 PERIOD 19 EXAMPLES BY CATEGORY 36 1) BLASPHEMY/ INSULT/ DENIGRATION WOULD YOU LIKE TO TAKE BLOOD PRESSURE PILLS? - Nusret Çiçek 36 PHOTOGRAPH OF DISGRACE 38 2) ENMITY / WAR DISCOURSE WHERE IS THIS TAYYIP/TRAITORS RAVAGED AGAIN - Dogan News Agency (DHA) 40 SYRIAN CRISIS SPREADS ACROSS TURKEY – Yeni Çağ News Center 42 3) EXAGGERATION / ATTRIBUTION / DISTORTION ANGEL - DEVIL 44 “YOUNG AND HANDSOME MEHMET” and “KAVAK CIVIL REGISTRIES". /3 - Ali Kayıkçı 48 4) SYMBOLIZATION ALEVI REACTION TO IMPERTINENT HANS - Muhammet Erdoğan 49 YOU SHOULD NOT HAVE PLAYED POLITICS WITH TEARS! - Akın Aydın 50 OTHER DISADVANTAGED