Using Comedy to Build Community in Local Churches: How Laughing Together Can Bring People Together Jason T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Apostasy

The Great Apostasy R. J. M. I. By The Precious Blood of Jesus Christ; The Grace of the God of the Holy Catholic Church; The Mediation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Good Counsel and Crusher of Heretics; The Protection of Saint Joseph, Patriarch of the Holy Family and Patron of the Holy Catholic Church; The Guidance of the Good Saint Anne, Mother of Mary and Grandmother of God; The Intercession of the Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael; The Intercession of All the Other Angels and Saints; and the Cooperation of Richard Joseph Michael Ibranyi To Jesus through Mary Júdica me, Deus, et discérne causam meam de gente non sancta: ab hómine iníquo, et dolóso érue me Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam 2 “I saw under the sun in the place of judgment wickedness, and in the place of justice iniquity.” (Ecclesiastes 3:16) “Woe to you, apostate children, saith the Lord, that you would take counsel, and not of me: and would begin a web, and not by my spirit, that you might add sin upon sin… Cry, cease not, lift up thy voice like a trumpet, and shew my people their wicked doings and the house of Jacob their sins… How is the faithful city, that was full of judgment, become a harlot?” (Isaias 30:1; 58:1; 1:21) “Therefore thus saith the Lord: Ask among the nations: Who hath heard such horrible things, as the virgin of Israel hath done to excess? My people have forgotten me, sacrificing in vain and stumbling in their way in ancient paths.” (Jeremias 18:13, 15) “And the word of the Lord came to me, saying: Son of man, say to her: Thou art a land that is unclean, and not rained upon in the day of wrath. -

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES in ISLAM

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES IN ISLAM Editiorial Board Baderin, Mashood, SOAS, University of London Fadil, Nadia, KU Leuven Goddeeris, Idesbald, KU Leuven Hashemi, Nader, University of Denver Leman, Johan, GCIS, emeritus, KU Leuven Nicaise, Ides, KU Leuven Pang, Ching Lin, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Platti, Emilio, emeritus, KU Leuven Tayob, Abdulkader, University of Cape Town Stallaert, Christiane, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Toğuşlu, Erkan, GCIS, KU Leuven Zemni, Sami, Universiteit Gent Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century Benjamin Nickl Leuven University Press Published with the support of the Popular Culture Association of Australia and New Zealand University of Sydney and KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). © Benjamin Nickl, 2020 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non-Derivative 4.0 Licence. The licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non- commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: B. Nickl. 2019. Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment: Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Further details about Creative Commons licences -

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By STUDIO)

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by STUDIO) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Female Studio Title Female + Signatory Company Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A+E Studios, LLC Knightfall 2 0 0% 2 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC Six 8 4 50% 4 50% 1 13% 3 38% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC UnReal 10 4 40% 6 60% 0 0% 2 20% 2 20% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC Lifetime Alameda Productions, LLC Love 12 4 33% 8 67% 0 0% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0 Alameda Productions, LLC Netflix Alcon Television Group, Expanse, The 13 2 15% 11 85% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Expanding Universe Syfy LLC Productions, LLC Amazon Hand of God 10 5 50% 5 50% 2 20% 3 30% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon I Love Dick 8 7 88% 1 13% 0 0% 7 88% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow Streaming Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Just Add Magic 26 7 27% 19 73% 0 0% 4 15% 1 4% 0 2 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Kicks, The 9 2 22% 7 78% 0 0% 0 0% 2 22% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Man in the High Castle, 9 1 11% 8 89% 0 0% 0 0% 1 11% 0 0 Reunion MITHC 2 Amazon Prime The Productions Inc. -

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

The Aesthetic Sensibility of Indie TV

The Aesthetic Sensibility of Indie TV Graig Uhlin, Oklahoma State University The 2008 financial crisis helped to usher in the end of the Sundance-Miramax era of American independent filmmaking by collapsing its funding model. Investment capital dried up, financing through advanced sales to foreign markets remained available only to select filmmakers, and a number of studio specialty divisions closed their doors. Television and streaming services stepped into this gap to provide indie film personnel more stable sources of distribution and exhibition. If we adhere to a definition of “indie” based on economics, then this transition has been a relatively smooth one: television productions have found ways to successfully translate the practices of indie film to successful shows. Take, for an example, the TBS series Search Party. Its creators Sarah-Violet Bliss and Charles Rogers previously directed the 2014 indie film Fort Tilden, a caustic take on the vapid elements of Brooklyn hipster culture, then were recruited to television by writer-producer Michael Showalter. Search Party is the first self-financed project from Jax Media, founded in 2011, and newly purchased by Imagine Entertainment. Jax is known for its auteur comedies – among them, Broad City and Difficult People – and its success partly stems from utilizing indie film’s small-scale budgeting strategies. Jax guarantees creative autonomy to marketable talent by keeping production costs low (typically $750,000 per episode). It limits shooting days and writing staffs, and incentivizes talent by funneling unspent budget back into the show. This streamlined approach is directly modeled on indie film (the Search Party producers routinely raise this comparison), demonstrating how indie film personnel have adapted to a shifting media landscape, in the absence of viable paths to stable work in filmmaking. -

THTR 474 Intro to Standup Comedy Spring 2021—Fridays (63172)—10Am to 12:50Pm Location: ONLINE Units: 2

THTR 474 Intro to Standup Comedy Spring 2021—Fridays (63172)—10am to 12:50pm Location: ONLINE Units: 2 Instructor: Judith Shelton OfficE: Online via Zoom OfficE Hours: By appointment, Wednesdays - Fridays only Contact Info: You may contact me Tuesday - Friday, 9am-5pm Slack preferred or email [email protected] I teach all day Friday and will not respond until Tuesday On Fridays, in an emergency only, text 626.390.3678 Course Description and Overview This course will offer a specific look at the art of Standup Comedy and serve as a laboratory for creating original standup material: jokes, bits, chunks, sets, while discovering your truth and your voice. Students will practice bringing themselves to the stage with complete abandon and unashamed commitment to their own, unique sense of humor. We will explore the “rules” that facilitate a healthy standup dynamic and delight in the human connection through comedy. Students will draw on anything and everything to prepare and perform a three to four minute set in front of a worldwide Zoom audience. Learning Objectives By the end of this course, students will be able to: • Implement the comic’s tools: notebook, mic, stand, “the light”, and recording device • List the elements of a joke and numerous joke styles • Execute the stages of standup: write, “get up”, record, evaluate, re-write, get back up • Identify style, structure, point of view, and persona in the work we admire • Demonstrate their own point of view and comedy persona (or character) • Differentiate audience feedback (including heckling) -

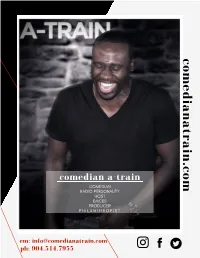

Comedian A-Train M COMEDIAN RADIO PERSONALITY HOST EMCEE PRODUCER P H I L a N T H R O P I S T

c o m e d i a n a t r a i n . c o comedian a-train m COMEDIAN RADIO PERSONALITY HOST EMCEE PRODUCER P H I L A N T H R O P I S T em: [email protected] ph: 904.514.7955 COMEDIAN A-TRAIN as seen and heard on bio Comedian A-Train, seen on WEtv’s Braxton Family Values, The Low Down with James Yon, River City Live, First Coast Living, and The Chat, is host of Yo Daddy’ Nem Podcast—iHeart Radio’s #1 Podcast in Duval, former co-host of Jacksonville’s #1 morning show, on 107.9 and Jacksonville’s #1 drive-time radio show on 103.7. He's a clean, traveling, stand-up, and corporate comedian, host and emcee. He tours with Original King of Comedy D. L. Hughley, and has toured with Kountry Wayne. He has featured for the biggest names in clean comedy, Michael Jr., viral sensation KevonStage, Dave Coulier (Uncle Joey on Full House), and Preacher Lawson (AGT). He's performed with Pete Lee (Jimmy Fallon and VH1’s Best Week Ever), Comedienne Dominique (Last Comic Standing), Bill Bellamy (Who's Got Jokes and Ladies Night Out), Ali Siddiq (Bring the Funny and Comedy Central), Loni Love (The Real), Deon Cole (Blackish and Grownish), Ronnie Jordan (Bossip), Huggy Low Down and Chris Paul (Tom Joyner Morning Show), and many others. Comedian A-Train has hosted the Zora Neal Hurston Festival, Orlando Jazz Festival, Steel City Jazz Festival— Birmingham, and Jacksonville Jazz Festival—the second largest in the country where he’s the first and only comedian to host in the city’s 40-year history. -

Exploring Racial Interpellation Through Political Satire Mahrukh Yaqoob

Exploring Racial Interpellation through Political Satire Mahrukh Yaqoob Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Masters of Arts in Criminology Department of Criminology Faculty of Social Science University of Ottawa © Mahrukh Yaqoob, Ottawa, Canada, 2020 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Professor Eduardo González Castillo for his guidance, encouragement, and support throughout this whole process. Thank you for your patience, kind words, and faith in me. I would like to express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to Professor Eduardo for being a great mentor and for always taking the time to listen and prioritize my work. I feel extremely fortunate to have worked with you and could not have completed this without your guidance and support. Above all, thank you for believing in my ability to succeed. I am truly honoured to have worked with you! Thank you to my family, especially my parents for all the sacrifices you made and for encouraging me to pursue opportunities that come my way. To my sisters, thank you for always being a shoulder to lean on. Lastly, thank you to my friends for always being there and for providing me with laughter and support. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………………………...ii Table of Contents ……………………………………………………………………………….iii Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………………….iv Introduction & Overview………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter 1: Theoretical Framework …………………………………………………………....7 1.1 -

Program Book

[FRONT COVER] Don’t Miss Silk Road Rising’s Next Show! [Image: Ultra American Poster] 2 016 DECEMBER 01-23 CHRISTMAS AT CHRISTINE’S THE WORLD PREMIERE Written and Performed by Azhar Usman | Directed by Aaron Todd Doug- las Written & Performed by September 6 - 25, 2016 Christine Bunuan Directed by J.R. Sullivan www.UltraAmerican.org [Image: Silk Road Rising Logo w Tagline] [Image: ComEd This new holiday musical revue puts a Silk Road spin on the Christmas season. Logo] [Image: NEA Logo] Chicago favorite Christine Bunuan invites you into her world with Christmas at Season Sponsor Production Sponsor___________ Christine’s. Journey from California to Chicago to the Philippines to a Catholic- September 6-25, 2016 Jewish household, as Christine sings her way through the holiday songbook and a lifetime of yuletide memories. THE WORLD PREMIERE Starring AZHAR USMAN TICKETS AND MORE INFORMATION AT Directed by AARON TODD DOUGLAS www.SilkRoadChristmas.org © www.UltraAmerican.org Season Sponsor Production Sponsor TEAM BIOS Azhar Usman is a standup comedian, actor, writer, and producer from Chicago. He was called “America’s Funniest Muslim” by CNN A World Premiere and was named among the “500 Most Influential Muslims in the Written & Performed by AZHAR USMAN World” by Georgetown University. Formerly an attorney, he has Directed by AARON TODD DOUGLAS worked as a performing artist and entertainment industry professional for over a decade. During that time, as co-creator of the internationally- acclaimed standup revue Allah Made Me Funny–The Official Muslim PRODUCTION TEAM Comedy Tour, he has toured over twenty-five countries, as well as comedy clubs, campuses, and theaters all over the United States. -

The 5Th Annual Desi Comedy Fest Lisa Geduldig, Publicist

The 5th Annual Desi Comedy Fest Lisa Geduldig, Publicist Cell: (415) 205-6515 • [email protected] • www.desicomedyfest.com For Immediate Release Contact: Lisa Geduldig – [email protected] June 8, 2018 (415) 205-6515 - Please don’t publish The Times of India Group Presents… The 5th Annual Desi Comedy Fest The biggest South Asian Comedy Festival in the US 11 days: August 9-19, 2018 9 Northern California cities: San Francisco, Berkeley, Mill Valley, Santa Cruz, Santa Clara, San Mateo, Milpitas, Dublin, and Mountain View Info/Tickets: www.desicomedyfest.com Facebook event page: www.facebook.com/desicomedyfest • Twitter: @desicomedyfest Press page: www.desicomedyfest.com/press Festival trailer: www.youtube.com/watch?v=V4Ew6b-1aBc San Francisco, CA… Bay Area-based Indian-born comedians, Samson Koletkar and Abhay Nadkarni, and The Times of India Group Present The 5th Annual Desi Comedy Fest, an 11- day South Asian stand up comedy extravaganza touring comedy clubs and theaters in 9 Northern California cities: San Francisco, Berkeley, Mill Valley, Santa Cruz, Santa Clara, San Mateo, Milpitas, Dublin, and Mountain View. The festival, the largest of its kind in the US, runs August 9-19 this year and features over 30 South Asian comedians from all over the US, with diverse ethnic (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Iranian, Syrian-Mexican, Libyan, Japanese, and Filipino) and religious backgrounds (Muslim, Jewish, Sikh, and Catholic). Last year’s festival boasted an attendance of 2700: up from 700 in 2014, the first year of the festival. 4000 attendees are expected this year. What’s new this year? This year, Koletkar and Nadkarni are partnering with The Times of India Group, India's largest media conglomerate, that just completed The Gaana Music Festival, the largest ever Indian music festival in America. -

Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two

########## Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two AU 9Gem AU 9Go! AU 9Life AU ABC AU ABC Comedy/ABC Kids NSW AU ABC Me AU ABC News AU ACCTV AU Al Jazeera AU Channel 9 AU Food Network AU Fox Sports 506 HD AU Fox Sports News AU M?ori Television NZ AU NITV AU Nine Adelaide AU Nine Brisbane AU Nine GO Sydney AU Nine Gem Adelaide AU Nine Gem Brisbane AU Nine Gem Melbourne AU Nine Gem Perth AU Nine Gem Sydney AU Nine Go Adelaide AU Nine Go Brisbane AU Nine Go Melbourne AU Nine Go Perth AU Nine Life Adelaide AU Nine Life Brisbane AU Nine Life Melbourne AU Nine Life Perth AU Nine Life Sydney AU Nine Melbourne AU Nine Perth AU Nine Sydney AU One HD AU Pac 12 AU Parliament TV AU Racing.Com AU Redbull TV AU SBS AU SBS Food AU SBS HD AU SBS Viceland AU Seven AU Sky Extreme AU Sky News Extra 1 AU Sky News Extra 2 AU Sky News Extra 3 AU Sky Racing 1 AU Sky Racing 2 AU Sonlife International AU Te Reo AU Ten AU Ten Sports AU Your Money HD AU ########## Crna Gora MNE ########## RTCG 1 MNE RTCG 2 MNE RTCG Sat MNE TV Vijesti MNE Prva TV CG MNE Nova M MNE Pink M MNE Atlas TV MNE Televizija 777 MNE RTS 1 RS RTS 1 (Backup) RS RTS 2 RS RTS 2 (Backup) RS RTS 3 RS RTS 3 (Backup) RS RTS Svet RS RTS Drama RS RTS Muzika RS RTS Trezor RS RTS Zivot RS N1 TV HD Srb RS N1 TV SD Srb RS Nova TV SD RS PRVA Max RS PRVA Plus RS Prva Kick RS Prva RS PRVA World RS FilmBox HD RS Filmbox Extra RS Filmbox Plus RS Film Klub RS Film Klub Extra RS Zadruga Live RS Happy TV RS Happy TV (Backup) RS Pikaboo RS O2.TV RS O2.TV (Backup) RS Studio B RS Nasha TV RS Mag TV RS RTV Vojvodina -

Pga01a36 Layout 1

Includes Family DVD section! Spring/Summer 2013 More Than 14,000 CDs and 210,000 Music Downloads Available at Christianbook.com! DVD— page A1 CD— CD— page 3 page 40 Christianbook.com 1–800–CHRISTIAN® New Releases THE BIBLE: MUSIC INSPIRED BY THE EPIC MINISERIES Table of Contents Discover songs that have been Accompaniment Tracks . .14, 15 inspired by the History Channel’s Bargains . .2, 38 epic miniseries! Includes “In Your Eyes” (Francesca Battis t elli); Collections . .4, 5, 7–9, 18–27, 33, 36, 37, 39 “Live Like That” (Sidewalk Proph - Contemporary & Pop . .28–31, back cover ets); “This Side of Heaven” (Chris August); “Love Come to Life” (Big Fitness Music DVDs . .21 Daddy Weave); “Crave” (For King Folios & Songbooks . .16, 17 & Country); “Home” (Dara MacLean); “Wash Me Away” (Point of Grace); “Starting Line” (Jason Castro); and more. Gifts . .back cover $ 00 Hymns . .24–27 WRCD88876 Retail $9.99 . .CBD Price 5 Inspirational . .12, 13 Instrumental . .22, 23 Kids’ Music . .18, 19 sher in the springtime season of renewal with Messianic . .10 Umusic and movies that will rejuvenate your spir- it! Filled with new items, bestsellers, and customer Movie DVDs . .A1–A36 favorites, these pages showcase great gifts to New Releases . .3–5, back cover treasure for yourself, as well as share with friends and family. And we offer our best prices possible— Praise & Worship . .6–9, back cover every day! Rock & Alternative . .32, 33, back cover Worship Jesus through song with new releases from Michael English (page 5) and Kari Jobe (back Scenic Music DVDs . .20 cover); keep on track with your healthy living goals Southern Gospel, Country & Bluegrass .