Winter Ecology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Foucauldian Analysis of Black Swan

Introduction In the 2010 movie Black Swan , Nina Sayers is filmed repeatedly practicing a specific ballet turn after her teacher mentioned her need for improvement earlier that day. Played by Natalie Portman, Nina is shown spinning in her room at home, sweating with desperation and determination trying to execute the turn perfectly. Despite the hours of gruesome rehearsal, Nina must nail every single aspect of this particular turn to fully embody the role she is cast in. After several attempts at the move, she falls, exhausted, clutching her newly twisted ankle in agony. Perfection, as shown in this case, runs hand in hand with pain. Crying to herself, Nina holds her freshly hurt ankle and contemplates how far she will go to mold her flesh into the perfectly obedient body. This is just one example in the movie Black Swan in which the main character Nina, chases perfection. Based on the demanding world of ballet, Darren Aronofsky creates a new-age portrayal of the life of a young ballet dancer, faced with the harsh obstacles of stardom. Labeled as a “psychological thriller” and horror film, Black Swan tries to capture Nina’s journey in becoming the lead of the ever-popular “Swan Lake.” However, being that the movie is set in modern times, the show is not about your usual ballet. Expecting the predictable “Black Swan” plot, the ballet attendees are thrown off by the twists and turns created by this mental version of the show they thought they knew. Similarly, the attendees for the movie Black Swan were surprised at the risks Aronofsky took to create this haunting masterpiece. -

Kingdom Principles

KINGDOM PRINCIPLES PREPARING FOR KINGDOM EXPERIENCE AND EXPANSION KINGDOM PRINCIPLES PREPARING FOR KINGDOM EXPERIENCE AND EXPANSION Dr. Myles Munroe © Copyright 2006 — Myles Munroe All rights reserved. This book is protected by the copyright laws of the United States of America. This book may not be copied or reprinted for commercial gain or profit. The use of short quotations or occasional page copying for personal or group study is permitted and encouraged. Permission will be granted upon request. Unless other- wise identified, Scripture quotations are from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNA- TIONAL VERSION Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (NKJV) are taken form the New King James Version. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Please note that Destiny Image’s publishing style capitalizes certain pronouns in Scripture that refer to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and may differ from some publishers’ styles. Take note that the name satan and related names are not capitalized. We choose not to acknowledge him, even to the point of violating grammatical rules. Cover photography by Andy Adderley, Creative Photography, Nassau, Bahamas Destiny Image® Publishers, Inc. P.O. Box 310 Shippensburg, PA 17257-0310 “Speaking to the Purposes of God for this Generation and for the Generations to Come.” Bahamas Faith Ministry P.O. Box N9583 Nassau, Bahamas For Worldwide Distribution, Printed in the U.S.A. ISBN 10: 0-7684-2373-2 Hardcover ISBN 13: 978-0-7684-2373-0 ISBN 10: 0-7684-2398-8 Paperback ISBN 13: 978-0-7684-2398-3 This book and all other Destiny Image, Revival Press, MercyPlace, Fresh Bread, Destiny Image Fiction, and Treasure House books are available at Christian bookstores and distributors worldwide. -

The Department of Children and Families Early Childhood Practice Guide for Children Aged Zero to Five

The Department of Children and Families Early Childhood Practice Guide for Children Aged Zero to Five The Department of Children and Families Early Childhood Practice Guide for Children Aged Zero to Five TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Title Page Introduction 3 Very Young Children in Child Welfare 4 Understanding the Importance of Attachment in Early Years 4 The Impact of Trauma on Early Childhood Development 10 Child Development 14 Social and Emotional Milestones (Charts) 17 Assessing Safety and Risk for Children 0‐5 – Intake and Ongoing Services 26 Quality Early Education and Care 38 Parents with Disabilities 39 Parents Who were in DCF Care as Children 43 Early Childhood – Adolescent Services 45 Visitation 46 The Role of Supervision in Early Childhood (Ages zero to five) 48 Consults 50 Foster Care: Focusing on Children Entering and In‐Care‐Birth to Age 5 51 DCF’s Teaming Continuum 53 Appendices 55 Appendices Index Page Introduction 56 The Impact of Trauma on Early Childhood Development 57 Child Development 61 Developmental Milestones 65 Attachment 70 Resources – Children’s Social and Emotional Competence 74 Cultural Considerations 75 Assessing Home Environment 76 Assessing Parenting and Parent/Child Relationship 78 Assessing Parental Capacity 78 Assessment of the Parent’s Perception of Child 79 Failure To Thrive 80 Abusive Head Trauma (Shaken Baby) 80 Foster Care 81 Fatherhood Initiative Programs at CJTS 82 Resources by Region (Separate Document) See “Resources” April 1, 2016 (New) 2 | Page The Department of Children and Families Early Childhood Practice Guide for Children Aged Zero to Five INTRODUCTION The Department of Children and Families supports healthy relationships, promotes safe and healthy environ‐ ments and assures that the social and emotional needs of all children are met. -

Deliver Me: Pregnancy, Birth, and the Body in the British Novel, 1900-1950

DELIVER ME: PREGNANCY, BIRTH, AND THE BODY IN THE BRITISH NOVEL, 1900-1950 BY ERIN M. KINGSLEY B.A., George Fox University, 2001 M.A., University of Colorado at Denver, 2006 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English 2014 This thesis, entitled: Deliver Me: Pregnancy, Birth, and the Body in the British Novel, 1900-1950 written by Erin M. Kingsley has been approved for the Department of English _______________________________________ Jane Garrity, Committee Chair _______________________________________ Laura Winkiel, Committee Member Date:_______________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. HRC protocol #__________________ iii ABSTRACT Kingsley, Erin (Ph.D., English, English Department) Deliver Me: Pregnancy, Birth, and the Body in the British Novel, 1900-1950 Thesis directed by Associate Professor Jane Garrity Deliver Me: Pregnancy, Birth, and the Body in the British Novel, 1900-1950 explores three ways British novels engage with the rise of the “culture of pregnancy,” an extreme interest in reproduction occurring during the modernist movement. This culture of pregnancy was intimately facilitated by the joint explosion of dailies and periodicals and the rise of “experts,” ranging from doctors presiding over the birthing chamber to self-help books dictating how women should control their birth-giving. In response to this culture of pregnancy, some modernist writers portray the feminine reproductive body as a suffering entity that can be saved by an alignment with traditionally- coded masculine aspects of the mind. -

Greek God Pantheon.Pdf

Zeus Cronos, father of the gods, who gave his name to time, married his sister Rhea, goddess of earth. Now, Cronos had become king of the gods by killing his father Oranos, the First One, and the dying Oranos had prophesied, saying, “You murder me now, and steal my throne — but one of your own Sons twill dethrone you, for crime begets crime.” So Cronos was very careful. One by one, he swallowed his children as they were born; First, three daughters Hestia, Demeter, and Hera; then two sons — Hades and Poseidon. One by one, he swallowed them all. Rhea was furious. She was determined that he should not eat her next child who she felt sure would he a son. When her time came, she crept down the slope of Olympus to a dark place to have her baby. It was a son, and she named him Zeus. She hung a golden cradle from the branches of an olive tree, and put him to sleep there. Then she went back to the top of the mountain. She took a rock and wrapped it in swaddling clothes and held it to her breast, humming a lullaby. Cronos came snorting and bellowing out of his great bed, snatched the bundle from her, and swallowed it, clothes and all. Rhea stole down the mountainside to the swinging golden cradle, and took her son down into the fields. She gave him to a shepherd family to raise, promising that their sheep would never be eaten by wolves. Here Zeus grew to be a beautiful young boy, and Cronos, his father, knew nothing about him. -

Benjamin Hood

Ice Whizz whizz my ice skates shoot over the cold hard ice. I hit a hairpin turn my feet fly out from under me I’m flying WUMP I land on the unforgiving ice. Ice is fun and playful but sometimes it takes is fun too far and womps you on the head Benjamin Hood Snow-boarding I love snow-boarding. I do it in all weathers. Snow or rain, sometimes in below zero. The reason I like snow-boarding is because I feel so alive. I fly by people. As I hit a jump I feel the air between my board and the ground. It’s very steep. I don’t stop, I keep going. I yell with freedom “woohoo!” I hit another jump. When I get to the bottom I go get something to eat. Then I sit by the fire. The warmth melts the cruel frost off my bones. Then I leave. Bradley Thane Ice skating Ice skating I haven’t been in two years. Snow, all over the ice. In the beginning I was scared, of falling and hurting myself All of a sudden… I fell, thud, onto the ice. My tooth went into my lip My Mom asked me I wanted my skates off, I said no. Two minutes later I was back on the ice. After that, It was like butter, the crinch, crunch under my skates, the slap of the hockey stick against the puck. It was the best night I ever had. By the end, the snow on the ice was gone. -

Your-Pregnancy.Pdf

Your Pregnancy excitement baby expectations dad boy mom birthfamily Henry Ford Health System welcomes you to our Women’s Health Services Department. The goal of our health care team is to make sure that you receive the very best care for you and your baby. The main purpose of prenatal care is to have a healthy mom and baby. Therefore, our approach is research-based and revolves around what has been proven to help both mom and baby through the pregnancy process. This is an exciting time for you and your family. We are committed partners in this process and have compiled this book as a resource of what to expect. In addition to this book, we have online resources that are available to you. We suggest you read through both of these resources and talk to your provider if you have questions or concerns. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. BABY & ME Baby and me - 40 weeks of growth and bonding ...................... 7 2. NUTRITION & EXERCISE Nutrition in pregnancy ......................................... 13 What should I eat? ............................................ 15 Vitamin D .................................................. 16 Anemia .................................................... 16 Staying healthy while pregnant .................................. 18 Safety precautions during pregnancy .............................. 20 3. TESTING Testing during pregnancy ....................................... 23 What to expect at your obstetric ultrasound ........................ 24 4. GENERAL HELP Common discomforts of pregnancy .............................. -

The Shattered Mirror: Identity, Authority, and Law, 58 Wash

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 58 | Issue 1 Article 3 Winter 1-1-2001 The hS attered Mirror: Identity, Authority, and Law Lawrence M. Friedman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence M. Friedman, The Shattered Mirror: Identity, Authority, and Law, 58 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 23 (2001), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol58/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Shattered Mirror: Identity, Authority, and Law Lawrence M. Friedman* At Stanford Law School, there are a stunning number of student organiza- tions. Some of them have been around for a while. Others come and go. We have or have had organizations of black students, Hispanic students, Native American students, Asian and Pacific Islander students, gay and lesbian students, Jewish students, Christian students, women students, older students, students interested in high technology, students interested in entertainment law. Most of these groups are identity groups. A few are groups organized around some field of law. When I went to law school, almost fifty years ago, there were (ifI am remembering correctly) none of these organizations. To be sure, there were very few women or minority students in law school at that time. -

Birth Settings in America: Outcomes, Quality, Access, and Choice (2020)

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/25636 SHARE Birth Settings in America: Outcomes, Quality, Access, and Choice (2020) DETAILS 265 pages | 6 x 9 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-66982-5 | DOI 10.17226/25636 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Susan Scrimshaw and Emily P. Backes, Editors; Committee on Assessing Health Outcomes by Birth Settings; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; FIND RELATED TITLES National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2020. Birth Settings in America: Outcomes, Quality, Access, and Choice . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25636. Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Birth Settings in America: Outcomes, Quality, Access, and Choice Prepublication Copy Uncorrected Proofs BIRTH SETTINGS IN AMERICA: OUTCOMES, QUALITY, ACCESS, AND CHOICE Committee on Assessing Health Outcomes by Birth Settings Susan Scrimshaw and Emily P. Backes, Editors Board on Children, Youth, and Families Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education Health and Medicine Division A Consensus Study Report of Copyright National Academy of Sciences. -

Becoming the Monstrous-Feminine: Sex, Death and Transcendence in Darren Aronofsky’S Black Swan

!" " Becoming the Monstrous-Feminine: Sex, Death and Transcendence in Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan Olivia Efthimiou Murdoch University [email protected] Abstract Black Swan (2010) makes its mark as a significant text in queer cinema. It artfully illustrates the complexities of femininity and the obliteration of conventional boundaries between masculine and feminine. This article discusses the application of Barbara Creed’s monstrous-feminine in the film and its importance for the queer monster of horror. Darren Aronofsky’s ballet dancer reveals the various incarnations of the monstrous-feminine. In particular, the figure of the Black Swan is explored as an expression of the female vampire. Natalie Portman’s character attempts to master the art of performing and being a woman, illustrating the conflation between life, performance and suffering through her ‘monstrous- in-process’. Her progressive de/trans-formation is defined by ‘sexual-becoming-towards- death’. Orgasm and abjection become signposts by which the artist achieves her ultimate goal of transcendence, producing a haunting representation of the monstrous sublime in the process. Key words: Queer cinema, horror film, vampire horror, gender theory, sublime Title Image: Production still taken from Black Swan (Aronofsky, 2010). IM 8:Masculine/Feminine < Monstrous-Feminine in Black Swan><O.Efthimiou>©IM/NASS 2012. ISSN 1833-0533" #" " Becoming the Monstrous-Feminine: Sex, Death and Transcendence in Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan Black Swan is the story of Nina Sayers, an introverted ballet dancer who wins the main part in a New York production of Swan Lake. Her role demands the successful portrayal of both the fragile White Swan and the dark temptress Black Swan. -

Developing Birth–Kindergarten Collections • Bilingual Books

Childrenthe journal of the Association for Library Service to Children &LibrariesVolume 7 Number 3 Winter 2009 ISSN 1542-9806 Developing Birth–Kindergarten Collections • Bilingual Books Library–School Collaboration: A Success Story • Celebrating Día PERMIT NO. 4 NO. PERMIT Change Service Requested Service Change HANOVER, PA HANOVER, Chicago, Illinois 60611 Illinois Chicago, PAID 50 East Huron Street Huron East 50 U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Association for Library Service to Children to Service Library for Association NONPROFIT ORG. NONPROFIT Table Contents● ofVolume 7, Number 3 Winter 2009 Notes 38 Bilingual Books For ESL Students . and Beyond 2 Editor’s Note Dawn Jeffers Sharon Verbeten 42 Latino Outreach 2 Executive Director’s Note Making Día a Fiesta of Family Literacy Aimee Strittmatter Mandee Kuglin 47 One School, One Book Features One Successful School–Library Collaboration 3 Award Acceptance Speeches Jan Bates and Nancy R. Webster Mildred L. Batchelder Award Fostering Moribito Arthur A. Levine and Cheryl Klein Departments Pura Belpré Author Award 7 Call for Referees The Soul of a Book Margarita Engle 51 Managing Children’s Services Pura Belpré Illustrator Award Flying with the Phoenixes An Ongoing Love of Colors and Stories Avoiding Job Burnout as a Librarian and a Manager Yuyi Morales Anitra Steele and the ALSC Managing Children’s Services Committee Arbuthnot Honor Lecture 53 Children and Technology The Geography of the Heart Beyond the Book Walter Dean Myers Literacy in the Digital Age Christopher Borawski and the ALSC Children and Technology 17 Early Essentials Committee Developing and Sustaining Birth- Kindergarten Library Collections 55 Special Collections Alan R. -

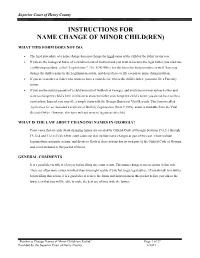

Instructions for Name Change of Minor Child(Ren)

Superior Court of Henry County INSTRUCTIONS FOR NAME CHANGE OF MINOR CHILD(REN) WHAT THIS FORM DOES NOT DO: • The legal procedure of a name change does not change the legal status of the child or the father in any way. • If you are the biological father of a child born out of wedlock and you want to become the legal father, you must use a different procedure, called “Legitimation.” The ADR Office has the forms for that procedure as well. You may change the child’s name in the Legitimation action, and do not have to file a separate name change petition. • If you are a mother or father who wants to have a court decide who is the child’s father, you must file a Paternity action. • If you are the natural parents of a child born out of wedlock in Georgia, and you have not married each other and want to change the child’s birth certificate to show the father and change the child’s name, you do not have to file a court action. Instead, you may file a simple form with the Georgia Bureau of Vital Records. This form is called Application for an Amended Certificate of Birth by Legitimation (form # 3929), and it is available from the Vital Records Office. However, this form will not serve to legitimate the child. WHAT IS THE LAW ABOUT CHANGING NAMES IN GEORGIA? Court cases that are only about changing names are covered by Official Code of Georgia Sections 19-12-1 through 19-12-4 and 31-10-23(d).