Poverty and Level of Human Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banking & Financial Statistics

Banking & Financial Statistics (Monthly) (Provisional) Deposit Credit 3800 3,668 3,697 3,614 3,561 3,565 3600 3,475 3,443 3,445 3,354 3,356 3400 3,333 3,210 3200 3,268 3,255 3,223 3,165 3,189 3000 3,090 3,038 3,056 2,977 Rs in in Billion Rs 2,920 2800 2,889 2,914 2600 2400 Mid Jun Mid Jul Mid Aug Mid Sep Mid Oct Mid Nov Mid Dec Mid Jan Mid Feb Mid Mar Mid Apr Mid May 2019 2019 2019 2019 2019 2019 2019 2020 2020 2020 2020 2020 Nepal Rastra Bank Banks & Financial Institution Regulation Department 2077 Baisakh Mid-May, 2020 Contents Page 1. Explanatory Notes 1 2. Major Financial Indicators 2 3. Statement of Assets & Liabilities of Banks & Financial Institutions 3 4. Profit & Loss Account of Banks & Financial Institutions 7 5. Statement of Sector wise, Product wise and Security wise Credit 11 6. Statement of Assets and Liabilities a. Commercial Banks 15 b. Development Banks 17 c. Finance Companies 22 7. Profit & Loss Account a. Commercial Banks 23 b. Development Banks 25 c. Finance Companies 28 8. Sector- wise, product-wise and security-wise credit a. Commercial Banks 31 b. Development Banks 33 c. Finance Companies 36 9. Micro-credit Development Banks a. Major Financial Indicators 39 b. Statement of Assets and Liabilities 39 c. Profit & Loss Account 39 39 10. Districtwise Branch List 40 11. Interest Rate Structure of Commercial Banks 42 Annexure 1. List of Bank and Financial Institutions with Short Name Annex 1 Explanatory Notes "Banking and Financial Statistics, Monthly" contains statistical information of NRB licensed 1 Banks and Financial Institutions (BFIs). -

Calendar Explanation

Calendar Explanation ॐ वक्रतुं ड महाकाय कोटिसूययसमप्रभ टिटवयघ्िुं क रु मे देव सवयकायेष सवयदा॥ rules. For example Ganesha Chaturthi has to be oserved when the Chaturthi Tithi is observed during the वटिष्ठ॥ यटममि ् पक्षे यत्र काले येि दृग्गटितै啍यम।् दृ�यते तेि पक्षेि क यायटिथ्याटदटििय म॥् 8th/15th part of the dinmana. The dinmana is the difference between local Sunset and Sunrise. If Chaturthi is not prevailing during that period then take the second day. भामकराचायय॥ यात्राटववाहोत्सवजातकादौ खेिैैः मफ िैरेवफलमफ ित्वम।् मयात्प्रो楍यते तेि िभश्चरािा ुं मफ िटक्रया दृग्गटितै啍यकृ द्या॥ For example, if one Tithi is observed at moonrise in India it may or may not exist during moonrise on the We are pleased to release the 2012 calendar based on Hindu dharma shastra and drika siddhanta. This same day in a different part of the world. If you are in America then it will be observed on previous day or calendar is specially prepared for the Greater Nadi, Fiji area, and it may not be applicable in other parts of the next day if you are in Japan, Fiji, Australia and other countries. For example if a total lunar eclipse is the world. All time presented here is adjusted for Daylight Saving Time. visible in India at 5:00 AM it will happen on the previous day in the USA. For these reasons Indian People usually align the Hindu festivals with the English dates based on the Indian calendar. -

Daan and Other Giving Traditions in India-Final.Qxd

Daan and Other Giving Traditions in India THE FORGOTTEN POT OF GOLD SANJAY AGARWAL Daan and Other Giving Traditions in India THE FORGOTTEN POT OF GOLD SANJAY AGARWAL Dedicated to Sh. Shekhar Agarwal, my brother, Guru, guardian, and friend, who first showed me the path of daan Published by AccountAidTM India 55-B, Pocket C, Siddharth Extension, New Delhi - 110014, India Phone No.: +91-11-2634 3852, +91-11-2634 3128 [email protected] www.accountaid.net First Edition: Delhi, 2010 Copyright © Sanjay Agarwal Price: `500 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the copyright owner of this book. While the greatest care has been taken in writing this book, no responsibility can be accepted by the publisher for the accuracy of the information presented. Daan and Other Giving Traditions in India ISBN 978-81-910854-0-2 Design and Layout: Moushumi De Illustrations: Mridula Sharma Printed at: PRINTWORKS, F-25, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase 1, New Delhi Contents at a Glance Foreword 09 Preface 14 I. Introduction 18 II. Daan and Utsarg (Hindu) 21 III. Sadaqa and Zakaat (Islam) 63 IV. Charity and Tithe (Christian) 71 V. Sewa and Daswandh (Sikh) 78 VI. Daan (Bauddh) 80 VII. Daan (Jain) 97 VIII. Other Traditions 102 IX. Leveraging Traditional Giving 106 Appendices 111 Works Cited 168 Notes 177 Index 229 Detailed Contents Foreword by Priya Viswanath 09 Foreword by Mark Sidel 12 Preface 14 Acknowledgements 16 I. -

Bamboo Garden 2013 Hindu Calendar

ॐ वक्रतुं ड महाकाय कोटिसूययसमप्रभ टिटवयघ्िुं क रु मे देव सवयकायेष सवयदा॥ Chaturthi Tithi is observed during the 8th/15th part of the dinmana. The dinmana is the difference between वटिष्ठ॥ यटममि ् पक्षे यत्र काले येि दृग्गटितै啍यम।् दृ�यते तेि पक्षेि क यायटिथ्याटदटििय म॥् local Sunset and Sunrise. If Chaturthi is not prevailing during that period then take the second day. भामकराचायय॥ यात्राटववाहोत्सवजातकादौ खेिैैः मफ िैरेवफलमफ ित्वम।् मयात्प्रो楍यते तेि िभश्चरािा ुं मफ िटक्रया दृग्गटितै啍यकृ द्या॥ For example, if one Tithi is observed at moonrise in India it may or may not exist during moonrise on the We are pleased to release the 2013 calendar based on Hindu dharma shastra and drika siddhanta. This same day in a different part of the world. If you are in America then it will be observed on previous day or calendar is specially prepared for the Greater Seattle area, and it may not be applicable in other parts of the the next day if you are in Japan, Fiji, Australia and other countries. For example if a total lunar eclipse is world. All time presented here is adjusted for Daylight Saving Time. visible in India at 5:00 AM it will happen on the previous day in the USA. For these reasons Indian Panchangam you bring from India cannot be used outside of India. People usually align the Hindu festivals with the English dates based on the Indian calendar. -

Nepal – NPL38943 – Malkabang – Myagdi

Country Advice Nepal Nepal – NPL38943 – Malkabang – Myagdi – Bikram Sambat – Nepali Calendar – Rashtriya Prajatantra Party-Nepal (RPP-N) – State Protection – Young Communist League – Police Protection 1 July 2011 1. Please provide a map of Myagdi region showing Malkabang village; Map 1: Location of Malkabang, Myagdi District1 2. Please provide information about the Nepali calendar, including (i) a method of conversion of dates from the Gregorian calendar to the Nepali calendar and vice versa, 1 „The Chantyal Language & People‟ (undated), University of Wisconsin website https://pantherfile.uwm.edu/noonan/www/Chantyal.html – Accessed 4 May 2011 – Attachment 1 Page 1 of 11 (ii) the Nepali dates for the following dates in the Gregorian calendar: January 2009 and 27 January 2009; and (iii) the dates in the Gregorian calendar which are equivalent to 2053 and 2054 in the Nepali calendar. (i) The Nepali calendar, known as Bikram Sambat, is approximately 56 years and 8½ months ahead of the Gregorian calendar. The Nepalese New Year falls in the middle of April. Unlike Gregorian months, the lengths of Nepali months are not predetermined, and change from year to year, varying from 29 days to 32 days.2 (ii) The Gregorian date 1 January 2009 is equivalent to 17/09/2065 in the Nepali Calendar The Gregorian date 27 January 2009 is equivalent to 14/10/2065 in the Nepali Calendar The ninth month of the Nepali calendar is Poush, which is equivalent to mid- December to mid-January. Mid-January to mid-February is known as Magh. Gregorian Bikram Sambat -

Nepali Calendar Nepali Calendar 2075 Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2075 Tihar 2075 Chath 2075 Teej 2075

nepalicalendar.rat32.com Nepali Calendar Nepali Calendar 2075 Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2075 Tihar 2075 Chath 2075 Teej 2075 Baisakh 2075 Nepali Calendar 2075 Baisakh Month rat32.com nepalicalendar.rat32.com Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2075 Tihar 2075 Chath 2075 Teej 2075 Jestha 2075 Nepali Calendar 2075 Jestha Month rat32.com nepalicalendar.rat32.com Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2075 Tihar 2075 Chath 2075 Teej 2075 Ashad 2075 Nepali Calendar 2075 Ashad Month rat32.com nepalicalendar.rat32.com Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2075 Tihar 2075 Chath 2075 Teej 2075 Shrawan 2075 Nepali Calendar 2075 Shrawan Month rat32.com nepalicalendar.rat32.com Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2075 Tihar 2075 Chath 2075 Teej 2075 Bhadra 2075 Nepali Calendar 2075 Bhadra Month rat32.com nepalicalendar.rat32.com Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2075 Tihar 2075 Chath 2075 Teej 2075 Ashoj 2075 Nepali Calendar 2075 Ashwin Month rat32.com nepalicalendar.rat32.com Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2075 Tihar 2075 Chath 2075 Teej 2075 Kartik 2075 Nepali Calendar 2075 Kartik Month rat32.com nepalicalendar.rat32.com Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan -

Academic Calendar 2076-2077 B.S

An associate of O V E R 1 0 Y E A R S O F A C A D E M I C E X C E L L E N C E NEPAL EDUCATION FOUNDATION-CONSORTIUM OF COLLEGES, NEPAL AITM Asian Institute of Technology & Management AITM NEPAL EDUCATION FOUNDATION-CONSORTIUM OF COLLEGES, NEPAL SUN MON TUE AsianW EInstituteD THU RofS FRI SAT Technology & Management Our Programs International Program Bachelor in Hotel Management (IMI) ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2076-2077 B.S. (2019-2020 A.D.) National Programs Bachelor in Civil Engineering AITM FOR ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE AND TOTAL PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT B. Tech in Biotechnology Satdobato, Khumaltar, Lalitpur, Nepal | Tel : +977-1-5548314, 5537852 | Email+2 : [email protected] & Management | URL : www.aitm.edu.np An associate of O V E R 1 0 Y E A R S O F A C A D E M I C E X C E L L E N C E AITM Asian Institute of Technology & Management NEPAL EDUCATION FOUNDATION-CONSORTIUM OF COLLEGES, NEPAL SUN MON TUE WED THURS FRI SAT Satdobato, Khumaltar, Lalitpur, Nepal | Tel : +977-1-5548314, 5537852 | Email : [email protected] | URL : www.aitm.edu.np An associate of O V E R 1 0 Y E A R S O F A C A D E M I C E X C E L L E N C E AITM Asian Institute of APR / MAY 2019 Technology & Management a}zfv @)&^ NEPAL EDUCATION FOUNDATION-CONSORTIUM OF COLLEGES, NEPAL SUN MON TUE WED THURS FRI SAT 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 28 29 30 May 1 2 3 4 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 29 30 31 12 13 14 Baishak 1 (Apr 14) Baishak 8-10 (Apr 21-23) Baishak 15 (May 28) Baishak 30 (May 13) New Year 2076 -

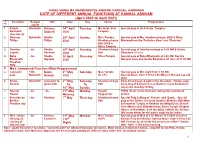

DATE of DIFFERENT ANNUAL FUNCTIONS at KANHAL ASHRAM (April 2020 to April 2021) S

SHREE SHREE MA ANANDAMAYEE ASHRAM, KANKHAL, HARIDWAR DATE OF DIFFERENT ANNUAL FUNCTIONS AT KANHAL ASHRAM (April 2020 to April 2021) S. Functions Bengali Tithi Date Day Venue Programmes No. month 1 Pahela Baishakh Krishna 14th April Tuesday Ma, Giriji, Shiv Special puja at all Ashram Temples Baishakh Saptami 2020 Temples (Nav Varsh) 2 Akshaya Baishakh Shukla 26th April Sunday Ma's Temple, Special puja of Ma, Shankaracharya, Giriji & Baba Tritiya Tritiya 2020 Shankaracharya Bholanath on the 'Pratistha divas' and 'Ghat-dan' Hall, Giriji & Shiva Temples 3 Shankar - do - Shukla 28th April Tuesday Shankaracharya Special puja of Shankaracharya at 9.00 AM & Sadhu Jayanti Panchmi 2020 Hall Bhandara (11 nos) 4 Baba - do - Shukla 30 April Thursday Shiva Temple Special puja of Baba Bholanath at 8.00 AM, Daridra Bholanath Saptami 2020 Narayan Seva and Sadhu Bhandara (21 nos) at 11.00 AM Tirodhan Tithi 5 Ma's Janmotsab Function (Main Programmes) a Janmadin 19th Sukla 2nd May Saturday Ma's Temple Special puja at Mid night from 2.30 AM. puja Baishakh Navami 2020 (A.J.P.) Special Maun from 3.15 to 3.45 AM and Akhand Jap will start. b Shata- Baishakh Janmadin to 2nd May Saturday Shankaracharya Daily Chandi puja & path in the forenoon. Hawan, puja Chandi janma tithi To To Hall & feeding of Kumari (9 nos), Batuk (1 no) & Sadhava (1 10th May Sunday no) on the last day 10 May c Special - do - - do - 11th May Monday Gayatri 10000 'Ahuti' in the forenoon duirng the Janmotsab Hawan Morning Yagyashala period. e Function on - do - Purnima 7th May Thursday Shankaracharya Special Puja & Bhog of Kumari and Batuk . -

Draft Report Should Be Submitted by Latest 1St March 2010 and a Final Report by 10Th March 2010

Understanding Childhood Vulnerability in Poverty A Qualitative Appraisal of Situation in Mymensingh & Netrakona Save the Children in Bangladesh March 2010 Save the Children WE ARE the world’s leading independent organisation for children. OUR VISION is a world in which every child attains the right to survival, protection, development and participation. OUR MISSION is to inspire breakthroughs in the way the world treats children, and to achieve immediate and lasting change in their lives © Save the Children, 2010 This publication has been produced with the support of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. The views presented in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Save the Children or the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. Author: INCIDIN Bangladesh ii Acknowledgement First and foremost the study team owes to the children and their parents who had made time and had the patience of sharing their opinions and experience in the midst of the busy schedule. SUF and the project team of SARA have been most generous in linking the study team with the children, parents and other key informants at the grassroots level. We are deeply indebted to them for their supports. Niels Bentzen Country Representative and Shamsul Alam Bokul Deputy Country Representative of Save the Children Sweden-Denmark have been extremely supportive to the team. Shahida Begum Director, Education and Youth Employment program of SCSD has aptly guided the study process by ensuring coordination and conceptual clarities. Atik Anwar Chowdhury Program Coordinator (Social Protection) Education and Youth Employment Program of SCSD has offered the study team with continual supports and accompanied the study team from field level data collection to finalization of the report. -

Nepali Calendar Nepali Calendar 2077 Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2077 Tihar 2077 Chath 2077 Teej 2077

nepalicalendar.rat32.com Nepali Calendar Nepali Calendar 2077 Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2077 Tihar 2077 Chath 2077 Teej 2077 Baisakh 2077 Nepali Calendar 2077 Baisakh Month rat32.com nepalicalendar.rat32.com Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2077 Tihar 2077 Chath 2077 Teej 2077 Jestha 2077 Nepali Calendar 2077 Jestha Month rat32.com nepalicalendar.rat32.com Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2077 Tihar 2077 Chath 2077 Teej 2077 Ashad 2077 Nepali Calendar 2077 Ashad Month rat32.com nepalicalendar.rat32.com Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2077 Tihar 2077 Chath 2077 Teej 2077 Shrawan 2077 Nepali Calendar 2077 Shrawan Month rat32.com nepalicalendar.rat32.com Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2077 Tihar 2077 Chath 2077 Teej 2077 Bhadra 2077 Nepali Calendar 2077 Bhadra Month rat32.com nepalicalendar.rat32.com Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2077 Tihar 2077 Chath 2077 Teej 2077 Ashoj 2077 Nepali Calendar 2077 Ashwin Month rat32.com nepalicalendar.rat32.com Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan Bhadra Ashoj Kartik Mangshir Poush Magh Falgun Chaitra Dashain 2077 Tihar 2077 Chath 2077 Teej 2077 Kartik 2077 Nepali Calendar 2077 Kartik Month rat32.com nepalicalendar.rat32.com Baisakh Jestha Ashad Shrawan -

Household Livelihood Security Assessments

Household Livelihood Security Assessments A Toolkit for Practitioners July, 2002 Prepared by: TANGO International Inc. Tucson, Arizona Prepared for: CARE USA, PHLS Unit 151 Ellis Street, Atlanta, Georgia 30303 This document was made possible in part Copies of this document can be through support provided by the Office of obtained from: Food for Peace, US Agency for International Development under the terms of CARE’s CARE USA, PHLS Unit, 151 Ellis Institutional Support Assistance Award Street, Atlanta, Georgia, 30303-2440 FAO-A-00-98-00055-00. The opinions Tel: 404-979-9127 expressed herein are those of CARE and do Fax: 404-589-2625 not necessarily reflect the views of the US Agency for International Development. It or may be reproduced, if credit is given to CARE. M. Katherine McCaston Household Livelihood Security Coordinator, CARE USA, PHLS Recommended citation: Unit, [email protected] CARE (electronic copies only) Household Livelihood Security Assessments: A Toolkit for Practitioners, Prepared for the PHLS Unit by: TANGO International Inc., Tucson, Arizona 2002 Authors: Timothy R. Frankenberger, TANGO International Inc. Kristina Luther, TANGO International Inc. James Becht, TANGO International Inc. M. Katherine McCaston, CARE USA Acknowledgments: This document, compiled and drafted by TANGO International, is the result of the work of many CARE staff. Household Livelihood Security Assessment work has benefited and evolved over the years due to the experimentation, testing, and refinement of diagnostic methods by key individuals in CARE as well as CARE Country Offices. The PHLS Unit would particularly like to thank Tim Frankenberger and Michael Drinkwater for their efforts to develop HLS Assessment conceptual models, tools, and methods. -

Embassy of Nepal, Tel Aviv नेपाली राजदतू ावास, तेल अबिि, इजरायल

Embassy of Nepal, Tel Aviv नेपाली राजदतू ावास, तेल अबिि, इजरायल Nepal’s Public Holidays for Nepalese Calendar 2069 B.S. (April 13, 2012 – April 13, 2013 A.D.) 1. April 13, 2012 (2069, Baishakh 01) Friday New Year’s Day 2. May 01, (Baishakh 19) Tuesday Workers’ Day (May Day) 3. May 06, (Baishakh 24) Sunday Gautam Buddha’s Birthday, Buddha Poornima (Ubhauli: Kirant, Rai, Limbu) 4. May 28, (Jestha 15) Monday Republic Day 5. August 02, (Shrawan 18) Thursday Janai Poornima/Raksha Bandhan 6. August 09, (Shrawan 25) Thursday Shrikrishna Janmashtami/Gaura Parba 7. September 18, (Ashwin 02) Tuesday Haritalika Teej- Festival (For women only) 8. September 20, (Ashwin 04) Thursday Rishi Panchami (For women only) 9. October 16, (Aswin 30) Tuesday Ghatasthapana - Dashain Festival 10. October 21, (Kartik 05) Sunday Phulpati - Dashain Festival 11. October 22, (Kartik 06) Monday Maha Ashtami - Dashain Festival 12. October 23, (Kartik 07) Tuesday Maha Nawami - Dashain Festival 13. October 24, (Kartik 08) Wednesday Bijaya Dashami - Dashain Festival 14. October 25, (Kartik 09) Thursday Ekadashi - Dashain Festival 15. October 26, (Kartik 10) Friday Dwadashi- Dashain Festival 16. October 29, (Kartik 13) Monday Kojagrat Poornima- Dashain Festival 17. November 13, (Kartik 28) Tuesday Laxmi Pooja/Deepawali - Tihar Festival 18. November 14, (Kartik 29) Wednesday Gobardhan /Mha Pooja/ Nepal Sambat- Tihar Festival 19. November 15, (Kartik 30) Thursday Bhai Tika (Brother’s Festival) - Tihar Festival 20. November 19, (Mangshir 04) Monday Chhath- Festival 21. December 25, (Paush 10) Tuesday Christmas Day 22. December 28, (Paush 13) Friday Udhauli Pooja/Mangsir Poornima/Yomari Punhi 23.