The Next Wave of the Suit-Era – a Forecasting Model of the Men’S Suit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charitably Chic Lynn Willis

Philadelphia University Spring 2007 development of (PRODUCT) RED, a campaign significantly embraced by the fashion community. Companies working with Focus on . Alumni Focus on . Industry News (PRODUCT) RED donate a large percentage of their profits to the Global Fund to fight Lynn Willis Charitably Chic AIDS. For example, Emporio Armani’s line donates 40 percent of the gross profit By Sara Wetterlin and Chaisley Lussier By Kelsey Rose, Erin Satchell and Holly Ronan margin from its sales and the GAP donates Lynn Willis 50 percent. Additionally, American Express, Trends in fashion come and go, but graduated perhaps the first large company to join the fashions that promote important social from campaign, offers customers its RED card, causes are today’s “it” items. By working where one percent of a user’s purchases Philadelphia with charitable organizations, designers, University in goes toward funding AIDS research and companies and celebrities alike are jumping treatment. Motorola and Apple have also 1994 with on the bandwagon to help promote AIDS a Bachelor created red versions of their electronics and cancer awareness. that benefit the cause. The results from of Science In previous years, Ralph Lauren has the (PRODUCT) RED campaign have been in Fashion offered his time and millions of dollars to significant, with contributions totaling over Design. Willis breast cancer research and treatment, which $1.25 million in May 2006. is senior includes the establishment of health centers Despite the fashion industry’s focus on director for the disease. Now, Lauren has taken image, think about what you can do for of public his philanthropy further by lending his someone else when purchasing clothes relations Polo logo to the breast cancer cause with and other items. -

Overview of Fashion

Chapter01 vrv Overview of Fashion 1.1 UNDERSTANDING FASHION: INTRODUCTION AND DEFINITION Fashion has become an integral part of contemporary society. It is an omnipresent aspect of our lives and is one of the focal topics of the print and electronic media, television and internet, advertisements and window displays in shops and malls, movies, music and modes of entertainment etc. Fashion is a statement that signifies societal preferences created by individual and collective identities. The key to its core strength lies in its aspiration value, which means that people aspire to be fashionable. Fashion travels across geographical boundaries, history influencing and in turn, influenced by society. Though the term 'fashion' is often used synonymously with garment, it actually has a wider connotation. A garment is not fashion merely because it is worn. To become fashion, a garment has to reflect the socio-cultural ethos of the time. As a generic term, fashion includes all products and activities related to a 'lifestyle' - clothes, accessories, products, cuisine, furniture, architecture, mode of transportation, vacations, leisure activities etc. Fig 1.1 Evening gowns by Sanjeev Sahai Creative Director of Amethysta Viola Fashion has emerged as a globally relevant area of academic study which includes various aspects of fashion design, fashion technology and fashion management. Due to the wide range of human and social aspects within its ambit, it is also a topic of scholarly study by sociologists, psychologists and anthropologists. 1 01 v r v Its multi-faceted nature leads to numerous interpretations. For an average person, fashion could generally refer to a contemporary and trendy style of dressing being currently 'in' and which is likely to become 'out' by the next season or year. -

The Use of Trend Forecasting in the Product Development Process

THE USE OF TREND FORECASTING IN THE PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT PROCESS C TWINE PhD 2015 THE USE OF TREND FORECASTING IN THE PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT PROCESS CHRISTINE TWINE A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Apparel / Hollings Faculty the Manchester Metropolitan University 2015 Acknowledgements The completion of this research project owes a great deal of support and encouragement of my supervisory team, Dr. David Tyler, Dr. Tracy Cassidy as my adviser and the expert guidance of my Director of Studies Dr. Ji-Young Ruckman and Dr. Praburaj Venkatraman. Their experience and commitment provided inspiration and guidance throughout those times when direction was much needed. I am also indebted to all those who participated in the interviewing process which aided the data collection process and made this research possible. These included personnel from the trend forecasting agencies Promostyl, Mudpie, Trend Bible and the senior trend researchers from Stylesight, and Trendstop. The buyers and designers from the retailers Tesco, Shop Direct, Matalan, River Island, Mexx, Puma, Bench, Primark, H&M, ASOS and Boohoo. Thank you to my lovely family, David and Florence for their support and encouragement when I needed it most. i Declaration No portion of the work referred to in this thesis has been submitted in support of an application for another degree or qualification of this or any other university or institution of learning. Copyright© 2014 All rights reserved No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the author. -

2017 Xarisma Catalog-White Label

DIRECTORY CONTENT DIRECTORY 2 - 3 Welcome & Content Directory 4 Premium Blade Flag 5 Premium Teardrop Flag 6 Premium 90 Flag 7 Premium Shark Fin Flag 8 - 9 Premium Ad Flag Accessories 10 - 11 Traditional Ad Flags 12 - 13 Custom Flag 14 - 15 Euro Flag 16 Attention and Message Traditional Ad Flag 17 Attention and Message Blade Flag 18 - 19 Attention and Message Flags 20 - 21 Teardrop Specialty Flags 22 - 23 Golf and Stick Flags 24 - 25 Run Through Banner and Spirit Flag 26 Car Flag and Tailgating Flag Pole 27 5M Flag and Promo Flag 28 - 29 Garden Flags and House Pole Kits 30 - 31 Lollipop Sign and Drive-Thru Display 32 - 33 Taut N Tight Spike, Door Frame Display and Trek Retractor 34 - 35 Realty Signs and A-Frames 36 - 37 Yard Signs and Rigid Sign Material 38 - 39 Deluxe Signicade® and Roll N’ Go Sign 40 - 41 Textile Aframes, Human Directionals and Sidewalk Display 42 - 43 Sky Dancer and Infatable Displays 44 - 45 Infatable X-Gloo Tent 46 - 47 Infatable Display and Furniture 48 - 49 Custom Banner Materials 50 - 51 Pennant Strings and Step and Repeat Banner Rolls 52 - 53 Window Clings and Floor Adhesives 54 - 55 Custom Wallpaper and Wall Adhesives 56 - 57 Custom Canvas and Free Floating Frames 58 - 59 Silicone Edge Graphic Frames 60 - 61 SEG Tradeshow Kits 62 - 63 Harmony Stretch Stand and Flat Wall Display 64 - 65 Standard and Curved Expandable Pop Ups 66 - 67 Arrow Tip Sign and Promotional Counters 68 - 69 Mini Table Top Displays 70 - 71 Superior and Select Retractable 72 - 73 Basic, Jumbo and SwitchBlade Retractable 74 - 75 X-Stand and Versatile Display 76 - 77 Drape and Box Fitted Table Covers 78 - 79 Stretch Table Cover and Table Runner/Throw 80 - 81 Convertible Table Cover and The Halo Display 82 - 83 Avenue Banners 84 - 85 The Commercial 86 - 87 The PRO Tent 88 - 89 Promo Tent 90 - 91 Tent Accessories and Walls 92 - 93 Patio Umbrellas 94 - 95 Premium Patio Umbrellas PAGE 2 G7 CERTIFIED The G7 Sytem Certifcation Program is a program that evaluates the merits of printing software applications to meet the G7 grayscale defnition. -

Entrepreneuring in Africa's Emerging Fashion Industry

Fashioning the Future Entrepreneuring in Africa’s Emerging Fashion Industry Langevang, Thilde Document Version Accepted author manuscript Published in: The European Journal of Development Research DOI: 10.1057/s41287-016-0066-z Publication date: 2017 License Unspecified Citation for published version (APA): Langevang, T. (2017). Fashioning the Future: Entrepreneuring in Africa’s Emerging Fashion Industry. The European Journal of Development Research, 29(4), 893-910. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-016-0066-z Link to publication in CBS Research Portal General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us ([email protected]) providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Fashioning the Future: Entrepreneuring in Africa’s Emerging Fashion Industry Thilde Langevang Journal article (Accepted version*) Please cite this article as: Langevang, T. (2017). Fashioning the Future: Entrepreneuring in Africa’s Emerging Fashion Industry. The European Journal of Development Research, 29(4), 893-910. DOI: 10.1057/s41287-016-0066-z This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of an article published in The European Journal of Development Research. The final authenticated version is available online at: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-016-0066-z * This version of the article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the publisher’s final version AKA Version of Record. -

The Fashion Runway Through a Critical Race Theory Lens

THE FASHION RUNWAY THROUGH A CRITICAL RACE THEORY LENS A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Sophia Adodo March, 2016 Thesis written by Sophia Adodo B.A., Texas Woman’s University, 2011 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Tameka Ellington, Thesis Supervisor ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Kim Hahn, Thesis Supervisor ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Amoaba Gooden, Committee Member ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Catherine Amoroso Leslie, Graduate Studies Coordinator, The Fashion School ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Linda Hoeptner Poling, Graduate Studies Coordinator, The School of Art ___________________________________________________________ Mr. J.R. Campbell, Director, The Fashion School ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Christine Havice, Director, The School of Art ___________________________________________________________ Dr. John Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... iii CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. -

Techniques of Fashion Earrings Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TECHNIQUES OF FASHION EARRINGS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Deon Delange | 72 pages | 01 Sep 1995 | Eagles View Publishing | 9780943604442 | English | Liberty, Utah, United States Techniques of Fashion Earrings PDF Book These stunning geometric earrings are perfect for a night out on the town or a shopping trip with the girls. And even if you don't go straight over your pencil lines, just kind of go with the flow; let your body feel it as you go. Trends influence what all of us wear to some extent, which is fine. Brendan How to draw human body for fashion design? Do share with us your creations! Two completely different looks, one set of clothe. Spice up some simple silver hoops with this awesome video tutorial for how to make bead earrings. You'll end up losing yourself. My advice? Make a note of the combinations you like if that helps to trigger your memory later. Stringing beads on multiple wires. The days of only wearing one tone of metal is over. When it comes to DIY jewelry, beaded earrings are some of the prettiest patterns out there. As an illustration, one pair of earring contains three hanging flowers: gentle pink, pale purple, and deep purple. Your email address will not be published. Tutorial Features: This beaded Christmas tree pattern will teach you how to make peyote stitch earrings and a peyote stitch necklace. All these bangle styles may be worn in one or each arms relying in your outfit, model and occasion. Eco-friendly jewellery. Try some dangling pearl earrings with a summer print for a fun and flirty look. -

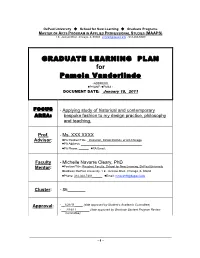

GRADUATE LEARNING PLAN for Pamela Vanderlinde

DePaul University School for New Learning Graduate Programs MASTER OF ARTS PROGRAM IN APPLIED PROFESSIONAL STUDIES (MAAPS) 1 E. Jackson Blvd., Chicago, IL 60604 [email protected] (312-362-8448) GRADUATE LEARNING PLAN for Pamela Vanderlinde •ADDRESS: •PHONE: •EMAIL: DOCUMENT DATE: January 18, 2011 FOCUS - Applying study of historical and contemporary AREA: bespoke fashion to my design practice, philosophy and teaching. Prof. - Ms. XXX XXXX Advisor: •PA Position/Title: _Instructor, Illinois Institute of Art-Chicago •PA Address: _____________________________________ •PA Phone: ______ •PA Email: Faculty - Michelle Navarre Cleary, PhD •Position/Title: Resident Faculty, School for New Learning, DePaul University Mentor: •Address: DePaul University, 1 E. Jackson Blvd., Chicago, IL 60604 •Phone: 312-362-7301______ •Email: [email protected] Cluster: - 86_______ - __1/21/11_____ (date approved by Student’s Academic Committee) Approval: - ___2/18/11________ (date approved by Graduate Student Program Review Committee) - 1 - PART I: Personal/Professional Background & Goals Directions: In Part I, the student provides a context for the Graduate Learning Plan and a rationale for both his/her career direction and choice of the MAAPS Program of study as a vehicle to assist movement in that direction. Specifically, Part I is to include three sections: A. a brief description of the student’s personal and professional history (including education, past/current positions, key interests, etc.); B. an explanation of the three or more years of experience (or equivalent) offered in support of the Graduate Focus Area; C. a brief description/explanation of the student’s personal and professional goals. A. Description of My Personal/Professional History: I have many passions in this world; fashion, teaching, travel, reading, yoga to name a few. -

Cloth, Fashion and Revolution 'Evocative' Garments and a Merchant's Know-How: Madame Teillard, Dressmaker at the Palais-Ro

CLOTH, FASHION AND REVOLUTION ‘EVOCATIVE’ GARMENTS AND A MERCHANT’S KNOW-HOW: MADAME TEILLARD, DRESSMAKER AT THE PALAIS-ROYAL By Professor Natacha Coquery, University of Lyon 2 (France) Revolutionary upheavals have substantial repercussions on the luxury goods sector. This is because the luxury goods market is ever-changing, highly competitive, and a source of considerable profits. Yet it is also fragile, given its close ties to fashion, to the imperative for novelty and the short-lived, and to objects or materials that act as social markers, intended for consumers from elite circles. However, this very fragility, related to fashion’s fleeting nature, can also be a strength. When we speak of fashion, we speak of inventiveness and constant innovation in materials, shapes, and colours. Thus, fashion merchants become experts in the fleeting and the novel. In his Dictionnaire universel de commerce [Universal Dictionary of Trade and Commerce], Savary des Bruslons assimilates ‘novelty’ and ‘fabrics’ with ‘fashion’: [Fashion] […] It is commonly said of new fabrics that delight with their colour, design or fabrication, [that they] are eagerly sought after at first, but soon give way in turn to other fabrics that have the charm of novelty.1 In the clothing trade, which best embodies fashion, talented merchants are those that successfully start new fashions and react most rapidly to new trends, which are sometimes triggered by political events. In 1763, the year in which the Treaty of Paris was signed to end the Seven Years’ War, the haberdasher Déton of Rue Saint-Honoré, Paris, ‘in whose shop one finds all fashionable merchandise, invented preliminary hats, decorated on the front in the French style, and on the back in the English manner.’2 The haberdasher made a clear and clever allusion to the preliminary treaty, signed a year earlier. -

Reading Print Ads for Designer Children's Clothing

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Communication Graduate Student Publication Communication Series October 2009 The mother’s gaze and the model child: Reading print ads for designer children’s clothing Chris Boulton UMass, Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/communication_grads_pubs Part of the Communication Commons Boulton, Chris, "The mother’s gaze and the model child: Reading print ads for designer children’s clothing" (2009). Advertising & Society Review. 5. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/communication_grads_pubs/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Graduate Student Publication Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This audience analysis considers how two groups of mothers, one affluent and mostly white and the other low-income and mostly of color, responded to six print ads for designer children’s clothing. I argue that the gender and maternal affiliations of these women—which coalesce around their common experience of the male gaze and a belief that children’s clothing represents the embodied tastes of the mother—are ultimately overwhelmed by distinct attitudes towards conspicuous consumption, in-group/out-group signals, and even facial expressions. I conclude that, when judging the ads, these mothers engage in a vicarious process referencing their own daily practice of social interaction. In other words, they are auditioning the gaze through which others will view their own children. KEY WORDS advertising, fashion, race, mothers, children BIO Chris Boulton is a doctoral student in Communication at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. -

Looking at the Past and Current Status of Kenya's Clothing and Textiles

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2018 Looking at the Past and Current Status of Kenya’s clothing and textiles Mercy V.W. Wanduara [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Wanduara, Mercy V.W., "Looking at the Past and Current Status of Kenya’s clothing and textiles" (2018). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 1118. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/1118 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings 2018 Presented at Vancouver, BC, Canada; September 19 – 23, 2018 https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/ Copyright © by the author(s). doi 10.32873/unl.dc.tsasp.0056 Looking at the Past and Current Status of Kenya’s clothing and textiles Mercy V. W. Wanduara [email protected] Abstract This paper analyzes and documents traditional textiles and clothing of the Kenyan people before and after independence in 1963. The paper is based on desk top research and face to face interviews from senior Kenyan citizens who are familiar with Kenyan traditions. An analysis of some of the available Kenya’s indigenous textile fiber plants is made and from which a textile craft basket is made. -

The Influence of Clothing on First Impressions: Rapid and Positive Responses

The influence of clothing on first impressions: Rapid and positive responses to minor changes in male attire Keywords: Clothing, first impressions, bespoke, influence, communication The influence of clothing on first impressions: Rapid and positive responses to minor changes in male attire. In a world that is becoming dominated by multimedia, the likelihood of people being judged on snapshots of their appearance is increasing. Social networking, dating websites and online profiles all feature people’s photographs, and subsequently convey a visual message to an audience. Whilst the salience of facial features is well documented, other factors, such as clothing, will also play a role in impression formation. Clothing can communicate an extensive and complex array of information about a person, without the observer having to meet or talk to the wearer. A person’s attire has been shown to convey qualities such as character, sociability, competence and intelligence (Damhorst, 1990), with first impressions being formed in a fraction of a second (Todorov, Pakrashi, and Oosterhof, 2009). This study empirically investigates how the manipulation of small details in clothing gives rise to different first impressions, even those formed very quickly. Damhorst (1990) states that ‘dress is a systematic means of transmission of information about the wearer’ (p. 1). A person’s choice of clothing can heavily influence the impression they transmit and is therefore a powerful communication tool. McCracken (1988) suggests that clothing carries cultural meaning and that this information is passed from the ‘culturally constructed world’ to clothing, through advertising and fashion. Clothes designers can, through branding and marketing, associate a new product or certain designs with an established cultural norm (McCracken, 1988).