Beverly Pepper in Artforum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 5, 1968

l \0 l . '3 e ,r,\. -t.n 0~qob -tel\9:\ e ~ f\'1e_. 10 orcnat' ~ ~ 1. lbblAM 11, IIRAUDE LIBRA.RV " 1..\ ~r,ce 1 '(t4 0 ":. .,. - DF TEMPLE BETH-EL - ' / • 1967 Highlighted By People, '\ Places, Organizations, War (Continued from Last Week) Jewish Theological Seminary of The Miriam Hospital, in its America. new tie with Brown University, Temple Beth Israel dedicated annotmced the joint appointment its new social hall, and the five- of Dr. Robert P. Davis as direc- year-old Barrington Jewish Cen- THE ONLY ENGLISH-JEWISH WEEKLY IN R. /. AND SOUTHEAST MASS. tor of the department of· medicine ter acquired its first full-time and professor of medical science rabbi, Rabbi Richard A. Weiss. at the university. Dr. Fiorindo A. Congregation Ohawe Shalom, VOL. LI, NO. 45 FRIDAY, JANUARY 5, 1968 15¢ PER COPY 16 PAGES Simeone was named di rector of P aw tu ck e t , al so engaged a the department of surgery at the spiritu~l leader, Rabbi Chaim ~r:mm:JP'.3P:J!'lrmrmr~nz1~~~~~~~~ hospital and professor of medical Raizman. science at Brown. Later in the Dr. Sidney Goldstein, chair- Bla•iberg's Daughter French Zionists Now fear year, Jerome R. Sapolsky became man of the Brown University De- Attends Hebrew Class executive director of The Miri- partment of Sociology and An- am. thropology, was named · to a During Transplant Possible Action By Police The first annual concert of l.Jnited Nations Ad Hoc Committee TEL AVIV - Jill Blaiberg · PARJS. -c..Rumors about pos- Israel manifestations of recent Jewish music was presented in of Experts on Urbanization to ad- of South Africa , who came to sible police action against Zionist days, the J ewisl!., Agency in Paris March at Temple Emanu-EI, to vise U Thant on the demographic Israel six months ago as a organizations and the possible clearly wishes to avoid any step mark Jewish Music Month. -

Rice Public Art Announces Four New Works by Women Artists

RICE PUBLIC ART ANNOUNCES FOUR NEW WORKS BY WOMEN ARTISTS Natasha Bowdoin, Power Flower, 2021 (HOUSTON, TX – January 26, 2021) In support of Rice University’s commitment to expand and diversify its public art collection, four original works by leading women artists will be added to the campus collection this spring. The featured artists are Natasha Bowdoin (b. 1981, West Kennebunk, ME), Shirazeh Houshiary (b. 1955, Shiraz, Iran), Beverly Pepper (b. 1922 New York, NY, d. 2020 Todi, Italy), and Pae White (b. 1963, Pasadena, CA). Three of the works are site-specific commissions. The Beverly Pepper sculpture is an acquisition of one of the last works by the artist, who died in 2020. Alison Weaver, the Suzanne Deal Booth Executive Director of the Moody Center for the Arts, said, “We are honored to add these extraordinary works to the Rice public art collection and are proud to highlight innovative women artists. We look forward to the ways these unique installations will engage students, faculty, staff, alumni and visitors in the spaces where they study, learn, live, work, and spend time.” Natasha Bowdoin’s site-specific installation will fill the central hallway of the renovated M.D. Anderson Biology Building, Shirazeh Houshiary’s glass sculpture will grace the lawn of the new Sid Richardson College, Beverly Pepper’s steel monolith will be placed adjacent to the recently completed Brockman Hall for Opera, and Pae White’s hanging sculpture will fill the rotunda of McNair Hall, home to the Jones Graduate School of Business. The four works will be installed in the first four months of the year and be on permanent view beginning May 1, 2021. -

Washington University Record, March 1, 1979

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Washington University Record Washington University Publications 3-1-1979 Washington University Record, March 1, 1979 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/record Recommended Citation "Washington University Record, March 1, 1979" (1979). Washington University Record. Book 129. http://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/record/129 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington University Publications at Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Record by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON Published for the Washington University Community UNIVERSITY i IN ST LOUIS Itoperfy of' Medical Library ■ ■ - j March 1,1979 wu •■■ rITL.1 Travel Policy Because the University does not have a central clearing- Insures house to record each em- WU Employes ploye's travels, Harig said tell- The stock image of univer- ing someone—a wife or hus- sity business is that of a pro- band or department secretary fessor teaching in a class- or chairman—of a trip's busi- room. But a great deal of Uni- ness intent is advised. versity-related business takes There are a number of place away from the cam- exclusions to the policy's pus—whether it is research, coverage. One exclusion in- guest lectures, conferences, volves the leasing of aircraft. policymaking or just errands. According to the travel policy, To insure its journeying em- an employe is not covered in ployes, WU has a travel acci- an aircraft operated by the dent policy that provides a employe, a member of his or $100,000 death benefit as well her household, or in an air- craft leased by the Univer- as benefits for dismember- Theodore V. -

T Magazine Beverly Pepper Profiled in T Magazine Sep 10, 2019

By Megan O’Grady Sept. 10, 2019, 1:00 p.m. ET IT’S EARLY ONE APRIL morning in Todi, Italy, and the installation is already underway: the four sculptures in pieces on a flatbed truck in the deserted piazza; the dawn sky lit a dramatic ombré, like a Giorgio de Chirico painting. Within the hour, the town begins to wake: flocks of schoolchildren, men and women oblivious to the russet-colored steel monoliths — each around 33 feet high and weighing about eight tons — slowly rising in their midst. The artist arrives, observing the scene from a small white car tucked in a corner of the piazza. “I get goose pimples,” she says. “It’s been 40 years.” It’s hard to imagine now, but in 1979, when the American sculptor and environmental artist Beverly Pepper first created the columns for this ancient Umbrian hill town, their presence was controversial. Monumental contemporary sculpture was novel here then, and Todi’s modest square, which dates at least to the 11th century, is itself a sacred space: The evening I arrived, I was met by the face of Christ, his blurry visage projected on the duomo for the town festival. But traditionalists’ attitudes have changed, in large part because of the Brooklyn-born artist herself, who has made her home in Italy since the 1950s and has been an honorary citizen of Todi for a decade. Those Tuderti (as people from Todi are known) old enough to remember the columns’ first appearance speak with reverence for the woman who bends metal like paper, who makes chunks of steel transcendent; their return, they say, feels like a necessary correction. -

Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 By

Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 by Christopher M. Ketcham M.A. Art History, Tufts University, 2009 B.A. Art History, The George Washington University, 1998 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ARCHITECTURE: HISTORY AND THEORY OF ART AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2018 © 2018 Christopher M. Ketcham. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author:__________________________________________________ Department of Architecture August 10, 2018 Certified by:________________________________________________________ Caroline A. Jones Professor of the History of Art Thesis Supervisor Accepted by:_______________________________________________________ Professor Sheila Kennedy Chair of the Committee on Graduate Students Department of Architecture 2 Dissertation Committee: Caroline A. Jones, PhD Professor of the History of Art Massachusetts Institute of Technology Chair Mark Jarzombek, PhD Professor of the History and Theory of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Tom McDonough, PhD Associate Professor of Art History Binghamton University 3 4 Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 by Christopher M. Ketcham Submitted to the Department of Architecture on August 10, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture: History and Theory of Art ABSTRACT In the mid-1960s, the artists who would come to occupy the center of minimal art’s canon were engaged with the city as a site and source of work. -

Artlab Beverly Pepper CUT, CARVE, & SCULPT: Ancient Greek and Egyptian Traditions of Your Own Triad Representing Three Gods As One Entity

ArtLAB Beverly Pepper CUT, CARVE, & SCULPT: ancient Greek and Egyptian traditions of Your Own Triad representing three gods as one entity. Later Have you noticed the change in artworks in her life, Pepper developed sculptures at Westfield UTC mall? This year Museum using highly polished stainless steel with of Contemporary Art San Diego (MCASD) painted interiors. From the very beginning of is excited to present the work of American her career, she created works to be displayed sculptor Beverly Pepper and has designed outdoors--as they are here at the mall. playful artmaking activities for you to make at home. Explore Before you head home, take a closer look at Start exploring. Zeus Triad (1997-99). • What does this sculpture remind you of? About the Artist • How was it made? What do you notice Beverly Pepper (1922–2020) was an about the forms? American artist known for her monumental • How does the title complement the sculptures, land art, and site-specific composition or not? installations. She remained independent from any particular art movement and Are you now ready to create your own experimental in her practice. sculptures, inspired by Beverly Pepper’s Zeus Triad? Pepper created these stand-alone She began her artistic career at the age columns by carving a malleable material of sixteen, not much older than you. She such as wax or clay and then cast it in studied painting, design, and photography in bronze. New York and Paris and traveled extensively. Fun Fact After a trip to Angkor Wat, Cambodia, in Casting is a process in which a liquid material 1960, she was inspired by the temple ruins is usually poured into a mold of the desired surviving beneath the jungle growth. -

James Barron Art Beverly Pepper Octavia, 2015

James Barron Art Beverly Pepper Octavia, 2015 KENT, CT US +1 917 270 8044 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] BEVERLY PEPPER Octavia, 2015 Cor-Ten Steel 136 x 112 x 55 inches Base: 88 x 103 inches Base, signed “B.P. 2015” The corrugated crust-like surface of Octavia was created by dripping melted steel on in layers. This texture is unique to the work. “When you see shadows of it on the ground, it’s like the phases of the moon, and mom did note that. As those circular forms carve across the grass, it’s as if it’s a moon made of sunlight, as opposed to a moon made of moonlight.” Jorie Graham According to Jorie Graham, the executor of the Beverly Pepper Estate, Octavia embraces Pepper’s interest in dichotomies: heavy/light, danger/pleasure, male/female, gravitational/anti-gravitational. The work appears to hover precariously over the ground, despite its immense weight and stability. The tension between movement and stillness activates the work and the space around it. Pepper was also fascinated by sundials and by the phases of the moon; Octavia casts large curved shadows, which shift around the piece as the light changes throughout the day. Jorie Graham, photo © Jeannette Montgomery Barron “Monumental sculpture exists as experiential space. That is, it is neither entirely an external object, nor wholly an internal experience.” Beverly Pepper Bust of Octavia Minor at the Ara Pacis museum in Rome Octavia the Younger (Octavia Minor) was the older sister of Augustus, the first Roman Emperor, and the fourth wife of Mark Antony, prior to his marriage to Cleopatra. -

At 96, the Sculptor Beverly Pepper Is Only Now Getting Credit for Using Cor-Ten Steel Way Before Richard Serra.” Artnet News

Cascone, Sarah. “At 96, the Sculptor Beverly Pepper Is Only Now Getting Credit for Using Cor-Ten Steel Way Before Richard Serra.” Artnet News. 25 February 2019. Web. At 96, the Sculptor Beverly Pepper Is Only Now Getting Credit for Using Cor-Ten Steel Way Before Richard Serra At 96, Beverly Pepper is still making monumental sculptures. Beverly Pepper at the iron factory (2012). Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London. When one thinks of an artist who works with massive, rusted Cor-ten steel, Richard Serra might be the first name to come to mind. But it was actually 96-year-old Beverly Pepper who was the first artist to work with the material, way back in 1964. “I’m the first person—the first artist in America—to use Cor-Ten,” Pepper told the Smithsonian Archives of American Art’s oral history project in 2009. “US Steel said to me—because, you know, they liked me. I was this good-looking kid—’Beverly, why don’t you try this new material we have. It’s Cor-Ten.'” From this simple suggestion sprang a lifetime of work, monumental sculptures that are naturally weather-resistant, with surfaces that oxidize, turning to rich shades of reddish brown, a layer of rust that fends off corrosion and protects the material from moisture. The trademarked steel alloy material that soon became the staple of Pepper’s practice is at the heart of the artist’s new show in New York, “Beverly Pepper: Cor-Ten,” at Marlborough Contemporary through March 23. -

Landmarks Guide for Adolescents

Landmarks Guide for Adolescents Beverly Pepper American, born 1924 Harmonious Triad 1982–83 Cast ductile iron Subject: Harmony and unity Activity: Making a harmonious sculpture Materials: Styrofoam and popsicle sticks or chopsticks Vocabulary: Geometric Abstraction, symbolism, harmony Introduction Beverly Pepper was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1924. Before becoming a sculptor she was a painter. She studied in France and Italy with master sculptors like Fernand Leger, Alexander Calder, and David Smith. At the time, Pepper was one of the few female sculptors who worked in metal, and she was also one of the few sculptors who fabricated their own work (most artists had their large metal works made in factories). Pepper is interested in expressing timeless human experiences and emotions through geometric forms. This is a style called Geometric Abstraction. In Harmonious Triad, she created three columns that are alike but unique. By placing them in a row, these three similar objects create a composition that is interesting and varied, but that still has unity and balance as a whole. Questions What human experiences or emotions How does the title influence our might Pepper be representing in this understanding of the work? work? Why do you think so? Does this piece resemble columns or totems? Where do we usually find columns or totems? What function do these forms usually represent? Beverly Pepper, continued Activity Using styrofoam as a base, insert popsicle sticks or chopsticks into the foam so that they stand vertically. Experiment with arranging them to create a composition that utilizes visual harmony and unity. Try using equal numbers of vertical lines and repetition to achieve the effect. -

Meijer Gardens Announces Landmark Gift from Sculptor Beverly Pepper

EMBARGOED UNTIL TUESDAY, DECEMBER 20 AT 5 AM CONTACT: John VanderHaagen | Public Relations Manager | 616-975-3155 | [email protected] MEIJER GARDENS ANNOUNCES THE LANDMARK GIFT OF BEVERLY PEPPER PRINT AND DRAWING ARCHIVES AND CAREER-SPANNING RETROSPECTIVE IN 2018 Meijer Gardens will become the permanent home to Beverly Pepper’s personal archive of hundreds of drawings, prints, sketchbooks and works on paper. GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. — December 20, 2016 — In conjunction with the 94th birthday of iconic American sculptor Beverly Pepper, Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park is honored to announce the gift of Pepper’s expansive print and drawing archives to its permanent collection. Seven decades of work are included. The extraordinary gift from Pepper, one of the pioneering Contemporary sculptors, includes hundreds of drawings, prints, works on paper and notebooks – many containing sketches of her major sculptural endeavors. Meijer Gardens will become the repository of her two-dimensional legacy spanning her career, beginning in the 1950s. Pepper is world-renowned for her work, which often incorporates industrial metals like iron, bronze, stainless steel and stone into sculptural of a monumental scale, but her vast drawing and print repertoire is lesser known. Although never formally associated with any particular “school”, her concern for abstraction and commitment to materials ran parallel to David Smith with whom she was very close, developing with those of Richard Serra, Mark di Suvero and Richard Hunt. In his recent monograph on Pepper, the noted art historian Robert Hobbs writes, “an American living mainly in Italy since the 1950s and an artist with an enviable reputation beginning in the early 1960s, Beverly Pepper, together with the two “Louises” – Bourgeois and Nevelson- heads the list of outstanding American women sculptors achieving artistic maturity in the mid-twentieth century.” “The enormity of Beverly Pepper’s gift cannot be understated,” states Joseph Antenucci Becherer, Chief Curator and Vice President of Meijer Gardens. -

IL FESTIVAL DELLE ARTI 2021 RENDE OMAGGIO AD ARNALDO POMODORO Todi: 24 Luglio - 26 Settembre

COMUNICATO STAMPA IL FESTIVAL DELLE ARTI 2021 RENDE OMAGGIO AD ARNALDO POMODORO Todi: 24 Luglio - 26 Settembre Todi, 4 Maggio 2021 - Dopo il successo della prima edizione, tenutasi tra Todi, L’Aquila e Venezia in omaggio all’artista statunitense Beverly Pepper, torna in Umbria, per il secondo anno, l’atteso appuntamento con il Festival delle Arti, a cura di Francesca Valente. Promosso dalla Fondazione Progetti Beverly Pepper, l’evento è realizzato in collaborazione con il Comune di Todi, vero e proprio “rifugio” dell’artista dal 1970 anno in cui, affascinata dalla bellezza artistica e monumentale del luogo, vi si stabilì con il marito, lo scrittore e giornalista Curtis Bill Pepper, fino alla sua scomparsa nel Febbraio del 2020. L’edizione 2021 del Festival delle Arti pone le sue solide basi sulla storica amicizia tra Beverly Pepper e uno dei più grandi scultori contemporanei italiani, Arnaldo Pomodoro, al quale l’evento renderà quest’anno un ampio e diffuso omaggio, in collaborazione con la Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro di Milano. Il primo incontro tra Arnaldo Pomodoro e Beverly Pepper risale al 1962, in occasione della mostra Sculture nella città, ideata e curata da Giovanni Carandente per il Festival dei Due Mondi di Spoleto e oggi considerata una pietra miliare nella storia dell’arte del Novecento. Per la prima volta, infatti, l’arte contemporanea viene esposta all’aperto e le sculture di giovani e talentuosi artisti, tra cui la Pepper e Pomodoro, vengono messe a confronto con la città e i suoi spazi pubblici. Quel momento segna tra i due scultori l’inizio di un rapporto professionale e personale di reciproca stima e amicizia, nel comune intento di costruire un linguaggio artistico in dialogo costante con l’ambiente e la natura. -

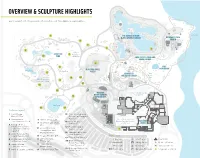

Overview & Sculpture Highlights

OVERVIEW & SCULPTURE HIGHLIGHTS For a complete list of our permanent collection, visit MeijerGardens.org/sculpture 8 THE RICHARD & HELEN Wetlands DeVOS JAPANESE GARDEN MICHIGAN’S FARM GARDEN Nature’s Niches 6 5 The Thicket 4 3 9 Doehne SCULPTURE 7 Wildflower 10 PARK Meadow GWEN FROSTIC WOODLAND The Glen SHADE GARDEN 2 15 FREY DeVOS VAN ANDEL BOARDWALK Waterfalls The Hollow 11 PIAZZA LENA MEIJER Wege CHILDREN’S GARDEN Nature 19 20 Trail Harvey Lemmen 14 Sculpture Gallery 21 12 Cultural Commons 13 East Beltline FREDERIK Volunteer Tribute Garden MEIJER GARDENS Coming Soon 18 AMPHITHEATER The Grove 16 17 Sculpture Legend 1 Tony Cragg, 15 Claes Oldenburg & Bent of Mind Coosje van Bruggen, Plantoir 2 Nina Akamu, 8 Keith Haring, Julia Tassell-Wisner-Bottrall The American Horse 16 Kenneth Snelson, English Perennial Garden WELCOME 9 Alexander Liberman, B-Tree II Coming Soon CENTER 3 George Rickey, Aria Meijer-Shedleski East Recieving Four Open Squares 17 Beverly Pepper, Picnic Pavilion Deliveries Only 10 Louise Nevelson, Horizontal Gyratory- Galileo’s Wedge 1 Tapered Atmosphere and Environment XI 18 Jonathan Borofsky, 4 Andy Goldsworthy, Male/Female Grand Rapids Arch 11 Auguste Rodin, Eve Map Legend 19 Roxy Paine, Neuron 5 Richard Hunt, Column 12 Anthony Caro, Walkways Information Coatroom of the Free Spirit Emma Sail 20 Chakaia Booker, Rendezvous and Boardwalk Eating Area Mobility Center 13 Henry Moore, 6 Jaume Plensa, Urban Excursion I, you, she or he... Bronze Form Stone Path Vending Tornado Shelter 21 Deborah Butterfield, Restrooms Drinking