Remembering Paul Cohen (1934–2007) Peter Sarnak, Coordinating Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LINEAR ALGEBRA METHODS in COMBINATORICS László Babai

LINEAR ALGEBRA METHODS IN COMBINATORICS L´aszl´oBabai and P´eterFrankl Version 2.1∗ March 2020 ||||| ∗ Slight update of Version 2, 1992. ||||||||||||||||||||||| 1 c L´aszl´oBabai and P´eterFrankl. 1988, 1992, 2020. Preface Due perhaps to a recognition of the wide applicability of their elementary concepts and techniques, both combinatorics and linear algebra have gained increased representation in college mathematics curricula in recent decades. The combinatorial nature of the determinant expansion (and the related difficulty in teaching it) may hint at the plausibility of some link between the two areas. A more profound connection, the use of determinants in combinatorial enumeration goes back at least to the work of Kirchhoff in the middle of the 19th century on counting spanning trees in an electrical network. It is much less known, however, that quite apart from the theory of determinants, the elements of the theory of linear spaces has found striking applications to the theory of families of finite sets. With a mere knowledge of the concept of linear independence, unexpected connections can be made between algebra and combinatorics, thus greatly enhancing the impact of each subject on the student's perception of beauty and sense of coherence in mathematics. If these adjectives seem inflated, the reader is kindly invited to open the first chapter of the book, read the first page to the point where the first result is stated (\No more than 32 clubs can be formed in Oddtown"), and try to prove it before reading on. (The effect would, of course, be magnified if the title of this volume did not give away where to look for clues.) What we have said so far may suggest that the best place to present this material is a mathematics enhancement program for motivated high school students. -

Perspective the PNAS Way Back Then

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 94, pp. 5983–5985, June 1997 Perspective The PNAS way back then Saunders Mac Lane, Chairman Proceedings Editorial Board, 1960–1968 Department of Mathematics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637 Contributed by Saunders Mac Lane, March 27, 1997 This essay is to describe my experience with the Proceedings of ings. Bronk knew that the Proceedings then carried lots of math. the National Academy of Sciences up until 1970. Mathemati- The Council met. Detlev was not a man to put off till to cians and other scientists who were National Academy of tomorrow what might be done today. So he looked about the Science (NAS) members encouraged younger colleagues by table in that splendid Board Room, spotted the only mathe- communicating their research announcements to the Proceed- matician there, and proposed to the Council that I be made ings. For example, I can perhaps cite my own experiences. S. Chairman of the Editorial Board. Then and now the Council Eilenberg and I benefited as follows (communicated, I think, did not often disagree with the President. Probably nobody by M. H. Stone): ‘‘Natural isomorphisms in group theory’’ then knew that I had been on the editorial board of the (1942) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 28, 537–543; and “Relations Transactions, then the flagship journal of the American Math- between homology and homotopy groups” (1943) Proc. Natl. ematical Society. Acad. Sci. USA 29, 155–158. Soon after this, the Treasurer of the Academy, concerned The second of these papers was the first introduction of a about costs, requested the introduction of page charges for geometrical object topologists now call an “Eilenberg–Mac papers published in the Proceedings. -

Humanizing Mathematics and Its Philosophy a Review by Joseph Auslander

BOOK REVIEW Humanizing Mathematics and its Philosophy A Review by Joseph Auslander Communicated by Cesar E. Silva Humanizing Mathematics and its Philosophy: he wrote and coauthored with Philip Davis and Vera John- Essays Celebrating the 90th Birthday of Reuben Hersh Steiner several books and developed what he terms a Bharath Sriraman, editor Humanist philosophy of mathematics. He has also been a Birkhäuser, 2017 frequent book reviewer for Notices.1 Hardcover, 363 pages ISBN: 978-3-319-61230-0 Although he was not trained as a philosopher, Reuben Hersh has emerged as a major figure in the philosophy of mathematics. His Humanist view is probably the most cogent expression contrasting the dominant philosophies of Platonism and Formalism. Hersh has had a remarkable career. He was born in the Bronx, to immigrant working class parents. He graduated from Harvard at age nineteen with a major in English and worked for some time as a journalist, followed by a period of working as a machinist. He then attended the Courant Institute from which he obtained a PhD in 1962, under the supervision of Peter Lax. Hersh settled into a conventional academic career as a professor at The University of New Mexico, pursuing research mostly in partial differential equations. But beginning in the 1970s he wrote a number of expository articles, in Scientific American, Mathematical Reuben Hersh with co-author Vera John-Steiner Intelligencer, and Advances in Mathematics. Subsequently, signing copies of their book Loving and Hating Mathematics: Challenging the Myths of Mathematical Life Joseph Auslander is Professor Emeritus of Mathematics at the at the Princeton University Press Exhibit, JMM 2011. -

Prepared to Meet You Where You Are Annual Report 2019 Annual Message We Are Delighted to Present Our 2019 Annual Report

Prepared to Meet You Where You Are Annual Report 2019 Annual Message We are delighted to present our 2019 Annual Report. We must be prepared to meet people where they Finally, our heartfelt thanks go out to our entire Board, Every year, as we “look back,” we are amazed at how are and we’re doing just that. Our short list includes our volunteers and our 500-plus staff members— much CJE offers to the community. It is often hard a focus on the emerging field of digital health and social workers, nurses, care managers, bus drivers, to choose which programs and services to highlight. assistive technology, the highly-anticipated opening cooks, resident care assistants, therapists and a Very few organizations nationwide offer the breadth of of Tamarisk NorthShore, the thoughtful elevation of whole host of hardworking individuals—who provide programs and services that we do to enhance the lives educational programming for the Sandwich Generation services to more than 20,000 older adults and their of older adults in the Jewish and larger community. and the expansion of supportive services to seniors family members each year. With your continued who want to stay in their own homes safely and with support, we can keep moving forward with creativity In this report, we illustrate how CJE’s Continuum dignity. and intention to “meet people” wherever they are on of Care stands without walls—prepared to “meet” CJE’s Continuum of Care. people wherever they might be in life, utilizing any As we move closer to our 50-year milestone, CJE has of our 35-plus programs to address their individual a strong foundation on which to build for the future. -

A Beautiful Mind Christopher D

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons College of the Pacific aF culty Presentations All Faculty Scholarship 4-1-2006 A Beautiful Mind Christopher D. Goff University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facpres Part of the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Goff, C. D. (2006). A Beautiful Mind. Paper presented at Popular Culture Association (PCA) / American Culture Association (ACA) Annual Conference in Atlanta, GA. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facpres/485 This Conference Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the All Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of the Pacific aF culty Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Beautiful Mind: the queering of mathematics Christopher Goff PCA 2006 Atlanta The 2001 film A Beautiful Mind tells the exciting story of real-life mathematical genius John Nash Jr. According to the DVD liner notes, director Ron Howard points out that while “there is a lot of creativity in the story-telling,…we are presenting a real world. We approached this story as truthfully as possible and tried to let authenticity be our guide.” (emphasis in original) Moreover, lead Russell Crowe not only “immersed himself in … Sylvia Nasar’s acclaimed biography” of Nash, but he also suggested that the film be shot in continuity (scenes in sequential order) to imbue the film with even more authenticity. Howard agreed. The film enjoyed huge box office success, earning over $170 million, and collared four Academy Awards, including the ultimate: Best Picture. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Jürgen K. Moser 1928–1999

Jürgen K. Moser 1928–1999 A Biographical Memoir by Paul H. Rabinowitz ©2015 National Academy of Sciences. Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. J Ü RGEN KURT MOSER July 4, 1928–December 17, 1999 Elected to the NAS, 1971 After the death of Jürgen Moser, one of the world’s great mathematicians, the American Mathematical Society published a memorial article about his research. It is well worth beginning here with a lightly edited version of the brief introductory remarks I wrote then: One of those rare people with a gift for seeing mathematics as a whole, Moser was very much aware of its connections to other branches of science. His research had a profound effect on mathematics as well as on astronomy and physics. He made deep and important contributions to an extremely broad range of questions in dynamical systems and celestial mechanics, partial differen- By Paul H. Rabinowitz tial equations, nonlinear functional analysis, differ- ential and complex geometry, and the calculus of variations. To those who knew him, Moser exemplified both a creative scientist and a human being. His standards were high and his taste impeccable. His papers were elegantly written. Not merely focused on his own path- breaking research, he worked successfully for the well-being of math- ematics in many ways. He stimulated several generations of younger people by his penetrating insights into their problems, scientific and otherwise, and his warm and wise counsel, concern, and encouragement. My own experience as his student was typical: then and afterwards I was made to feel like a member of his family. -

The Role of Body Mass Index and Its Covariates in Emotion Recognition

THE ROLE OF BODY MASS INDEX AND ITS COVARIATES IN EMOTION RECOGNITION A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Angela Nicole Roberts Miller August, 2013 Dissertation written by Angela Nicole Roberts Miller A.A.S., Metropolitan Community Colleges, 2001 B.S., Wichita State University, 2003 B.A., University of Missouri- Kansas City, 2007 M.P.H., Wichita State University, 2005 M.A., Kent State University, 2010 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by ___________________________________, Co-Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Joel Hughes ___________________________________, Co-Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee John Gunstad ___________________________________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Katherine Rawson ___________________________________, Scott Olds ___________________________________, Colleen Novak Accepted by _______________________________, Chair, Department of Psychology Maria Zaragoza _______________________________, Associate Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Raymond A. Craig ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................................v LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. vi DEDICATION .................................................................................................................. vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................ -

JMETC Fall-Winter2013 Insides D04 FINAL

Journal of Mathematics Education at Teachers College Fall – Winter 2013 A C!"#$%& '( L!)*!%+,-. -" M)#,!/)#-0+ )"* -#+ T!)0,-"1 © Copyright 2013 by the Program in Mathematics and Education Teachers College Columbia University in the City of New York TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface v Connecting the Disparate Ideas of Mathematical Modeling and Creativity Andrew Sanfratello Articles 6 Mathematical Modeling, Sense Making, and the Common Core State Standards Alan H. Schoenfeld, University of California, Berkeley 18 Mathematical Modelling in European Education Rita Borromeo Ferri, University of Kassel, Germany 25 The Effects of Constraints in a Mathematics Classroom Patricia D. Stokes, Barnard College, Columbia University 32 Developing Creativity Through Collaborative Problem Solving Lillie R. Albert and Rina Kim, Boston College, Lynch School of Education 39 Summer Camp of Mathematical Modeling in China Xiaoxi Tian, Teachers College Columbia University Jinxing Xie, Tsinghua University 44 A Primer for Mathematical Modeling Marla Sole, Eugene Lang College the New School for Liberal Arts 50 Mathematical Creativity, Cohen Forcing, and Evolving Systems: Elements for a Case Study on Paul Cohen Benjamin Dickman, Teachers College Columbia University 60 Model Eliciting Activities: Fostering 21st Century Learners Micah Stohlmann, University of Nevada, Las Vegas 66 Fostering Mathematical Creativity through Problem Posing and Modeling using Dynamic Geometry: Viviani’s Problem in the Classroom José N. Contreras, Ball State University 73 Exploring Mathematical -

From Traditional Set Theory – That of Cantor, Hilbert, Gödel, Cohen – to Its Necessary Quantum Extension

From Traditional Set Theory – that of Cantor, Hilbert, G¨odel, Cohen – to Its Necessary Quantum Extension Edouard BELAGA Institut des Hautes Etudes´ Scientifiques 35, route de Chartres 91440 – Bures-sur-Yvette (France) Juin 2011 IHES/M/11/18 From Traditional Set Theory – that of Cantor, Hilbert, Gödel, Cohen – to Its Necessary Quantum Extension Dr. Edouard Belaga IRMA, Université de Strasbourg IHES, Bures-sur-Yvette June 16, 2011 1 Plan of the talk • Introduction. • Review of traditional set theory. • Summing up the traditional set theory’s results. • Starting anew. • Philosophical context. • New foundations of set theory. • References. 2 Introduction: the main points of the talk • The central theme of the talk. • A brief, suggestive review of traditional set theory and its failure to find a proper place for the Continuum. • Formalism for reviewing the veracity of traditional set theory. • Metaphysical considerations, old and new. • The role of “experimental physics” in processes of definition, understanding, study, and exploitation of the Continuum. • What next ? Enters quantum mechanics of light. • The original purpose of the present study, started with a preprint «On the Probable Failure of the Uncountable Power Set Axiom», 1988, is to save from the transfinite deadlock of higher set theory the jewel of mathematical Continuum — this genuine, even if mostly forgotten today raison d’être of all traditional set-theoretical enterprises to Infinity and beyond, from Georg Cantor to David Hilbert to Kurt Gödel to W. Hugh Woodin to Buzz Lightyear. 3 History of traditional set theory • Georg Cantor’s set theory and its metaphysical ambition, the Continuum Hypothesis, CH: 2!° = !1 (1874-1877). -

The 2011 Noticesindex

The 2011 Notices Index January issue: 1–224 May issue: 649–760 October issue: 1217–1400 February issue: 225–360 June/July issue: 761–888 November issue: 1401–1528 March issue: 361–520 August issue: 889–1048 December issue: 1529–1672 April issue: 521–648 September issue: 1049–1216 2011 Morgan Prize, 599 Index Section Page Number 2011 Report of the Executive Director, State of the AMS, 1006 The AMS 1652 2011 Satter Prize, 601 Announcements 1653 2011 Steele Prizes, 593 Articles 1653 2011–2012 AMS Centennial Fellowship Awarded, 835 Authors 1655 American Mathematical Society Centennial Fellowships, Deaths of Members of the Society 1657 1135 Grants, Fellowships, Opportunities 1659 American Mathematical Society—Contributions, 723 Letters to the Editor 1661 Meetings Information 1661 AMS-AAAS Mass Media Summer Fellowships, 1303 New Publications Offered by the AMS 1662 AMS Announces Congressional Fellow, 843 Obituaries 1662 AMS Announces New Blog for Job Seekers, 1603 Opinion 1662 AMS Congressional Fellowship, 1467 Prizes and Awards 1662 AMS Department Chairs Workshop, 1468 Prizewinners 1665 AMS Epsilon Fund, 1466 Reference and Book List 1668 AMS Holds Workshop for Department Chairs, 844 Reviews 1668 AMS Announces Mass Media Fellowship Award, 843 Surveys 1668 AMS Centennial Fellowships, Invitation for Applications Tables of Contents 1668 for Awards, 1466 AMS Email Support for Frequently Asked Questions, 326 AMS Holds Workshop for Department Chairs, 730 About the Cover AMS Hosts Congressional Briefing, 73 35, 323, 475, 567, 717, 819, 928, 1200, 1262, -

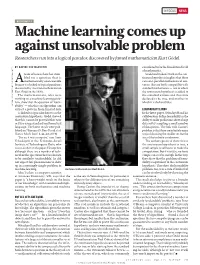

Machine Learning Comes up Against Unsolvable Problem Researchers Run Into a Logical Paradox Discovered by Famed Mathematician Kurt Gödel

IN FOCUS NEWS MATHEMATICS Machine learning comes up against unsolvable problem Researchers run into a logical paradox discovered by famed mathematician Kurt Gödel. BY DAVIDE CASTELVECCHI considered to be the foundation for all of mathematics. team of researchers has stum- Gödel and Cohen’s work on the con- bled on a question that is tinuum hypothesis implies that there mathematically unanswerable can exist parallel mathematical uni- Abecause it is linked to logical paradoxes verses that are both compatible with discovered by Austrian mathematician standard mathematics — one in which Kurt Gödel in the 1930s. the continuum hypothesis is added to The mathematicians, who were the standard axioms and therefore working on a machine-learning prob- declared to be true, and another in lem, show that the question of ‘learn- which it is declared false. ALFRED EISENSTAEDT/LIFE PICTURE COLL./GETTY PICTURE ALFRED EISENSTAEDT/LIFE ability’ — whether an algorithm can extract a pattern from limited data LEARNABILITY LIMBO — is linked to a paradox known as the In the latest paper, Yehudayoff and his continuum hypothesis. Gödel showed collaborators define learnability as the that this cannot be proved either true ability to make predictions about a large or false using standard mathematical data set by sampling a small number language. The latest result were pub- of data points. The link with Cantor’s lished on 7 January (S. Ben-David et al. problem is that there are infinitely many Nature Mach. Intel. 1, 44–48; 2019). ways of choosing the smaller set, but the “For us, it was a surprise,” says Amir size of that infinity is unknown.