Do Melancholic and Atypical Specifiers Reduce Heterogeneity In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dietary Patterns Are Differentially Associated with Atypical and Melancholic Subtypes of Depression

nutrients Article Dietary Patterns Are Differentially Associated with Atypical and Melancholic Subtypes of Depression Aurélie M. Lasserre 1,* , Marie-Pierre F. Strippoli 1 , Pedro Marques-Vidal 2 , Lana J. Williams 3, Felice N. Jacka 3, Caroline L. Vandeleur 1, Peter Vollenweider 2 and Martin Preisig 1 1 Department of Psychiatry, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, 1011 Lausanne, Switzerland; [email protected] (M.-P.F.S.); [email protected] (C.L.V.); [email protected] (M.P.) 2 Department of Medicine, Internal Medicine, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, 1011 Lausanne, Switzerland; [email protected] (P.M.-V.); [email protected] (P.V.) 3 Barwon Health, IMPACT—The Institute for Mental and Physical Health and Clinical Translation, Deakin University, Geelong 3220, Australia; [email protected] (L.J.W.); [email protected] (F.N.J.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-21-314-3552 Abstract: Diet has been associated with the risk of depression, whereas different subtypes of depres- sion have been linked with different cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs). In this study, our aims were to (1) identify dietary patterns with exploratory factor analysis, (2) assess cross-sectional associations between dietary patterns and depression subtypes, and (3) examine the potentially mediating effect of dietary patterns in the associations between CVRFs and depression subtypes. In the first follow-up of the population-based CoLaus|PsyCoLaus study (2009–2013, 3554 participants, 45.6% men, mean age Citation: Lasserre, A.M.; Strippoli, 57.5 years), a food frequency questionnaire assessed dietary intake and a semi-structured interview M.-P.F.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Williams, allowed to characterize major depressive disorder into current or remitted atypical, melancholic, L.J.; Jacka, F.N.; Vandeleur, C.L.; and unspecified subtypes. -

Is Your Depressed Patient Bipolar?

J Am Board Fam Pract: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.18.4.271 on 29 June 2005. Downloaded from EVIDENCE-BASED CLINICAL MEDICINE Is Your Depressed Patient Bipolar? Neil S. Kaye, MD, DFAPA Accurate diagnosis of mood disorders is critical for treatment to be effective. Distinguishing between major depression and bipolar disorders, especially the depressed phase of a bipolar disorder, is essen- tial, because they differ substantially in their genetics, clinical course, outcomes, prognosis, and treat- ment. In current practice, bipolar disorders, especially bipolar II disorder, are underdiagnosed. Misdi- agnosing bipolar disorders deprives patients of timely and potentially lifesaving treatment, particularly considering the development of newer and possibly more effective medications for both depressive fea- tures and the maintenance treatment (prevention of recurrence/relapse). This article focuses specifi- cally on how to recognize the identifying features suggestive of a bipolar disorder in patients who present with depressive symptoms or who have previously been diagnosed with major depression or dysthymia. This task is not especially time-consuming, and the interested primary care or family physi- cian can easily perform this assessment. Tools to assist the physician in daily practice with the evalua- tion and recognition of bipolar disorders and bipolar depression are presented and discussed. (J Am Board Fam Pract 2005;18:271–81.) Studies have demonstrated that a large proportion orders than in major depression, and the psychiat- of patients in primary care settings have both med- ric treatments of the 2 disorders are distinctly dif- ical and psychiatric diagnoses and require dual ferent.3–5 Whereas antidepressants are the treatment.1 It is thus the responsibility of the pri- treatment of choice for major depression, current mary care physician, in many instances, to correctly guidelines recommend that antidepressants not be diagnose mental illnesses and to treat or make ap- used in the absence of mood stabilizers in patients propriate referrals. -

Alteration of Immune Markers in a Group of Melancholic Depressed Patients and Their Response to Electroconvulsive Therapy

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author J Affect Manuscript Author Disord. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2017 February 03. Published in final edited form as: J Affect Disord. 2016 November 15; 205: 60–68. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.035. Alteration of Immune Markers in a group of Melancholic Depressed patients and their Response to Electroconvulsive Therapy Gavin Rush1,*, Aoife O’Donovan2,3,4,5, Laura Nagle1, Catherine Conway1, AnnMaria McCrohan2,3, Cliona O’Farrelly6, James V. Lucey1, and Kevin M. Malone2,3 1St. Patrick’s University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland 2School of Medicine and Medical Sciences, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland 3Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Mental Health Research, St. Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland 4Stress and Health Research Program, San Francisco Veteran’s Affairs Medical Center, San Francisco, California 5Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco, California 6School of Biochemistry and Immunology, University of Dublin Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland Abstract Background—Immune system dysfunction is implicated in the pathophysiology of major depression, and is hypothesized to normalize with successful treatment. We aimed to investigate immune dysfunction in melancholic depression and its response to ECT. Methods—55 melancholic depressed patients and 26 controls participated. 33 patients (60%) were referred for ECT. Blood samples were taken at baseline, one hour after the first ECT session, and 48 hours after ECT series completion. Results—At baseline, melancholic depressed patients had significantly higher levels of the pro- inflammatory cytokine IL-6, and lower levels of the regulatory cytokine TGF-β than controls. A significant surge in IL-6 levels was observed one hour after the first ECT session, but neither IL-6 nor TGF-β levels normalized after completion of ECT series. -

The Contemporary Jewish Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha

t HaRofei LeShvurei Leiv: The Contemporary Jewish Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha Senior Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Prof. Reuven Kimelman, Advisor Prof. Zvi Zohar, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts by Ezra Cohen December 2018 Accepted with Highest Honors Copyright by Ezra Cohen Committee Members Name: Prof. Reuven Kimelman Signature: ______________________ Name: Prof. Lynn Kaye Signature: ______________________ Name: Prof. Zvi Zohar Signature: ______________________ Table of Contents A Brief Word & Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………... iii Chapter I: Setting the Stage………………………………………………………………………. 1 a. Why This Thesis is Important Right Now………………………………………... 1 b. Defining Key Terms……………………………………………………………… 4 i. Defining Depression……………………………………………………… 5 ii. Defining Halakha…………………………………………………………. 9 c. A Short History of Depression in Halakhic Literature …………………………. 12 Chapter II: The Contemporary Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha…………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 d. Depression & Music Therapy…………………………………………………… 19 e. Depression & Shabbat/Holidays………………………………………………… 28 f. Depression & Abortion…………………………………………………………. 38 g. Depression & Contraception……………………………………………………. 47 h. Depression & Romantic Relationships…………………………………………. 56 i. Depression & Prayer……………………………………………………………. 70 j. Depression & -

The History of Depression in Neuroscience Morgan Hellyer

The History of Depression in Neuroscience Morgan Hellyer It is not a far stretch to say that philosophers and scientists have been examining depression for hundreds of years. Since around 400 BC when Hippocrates began using the terms “mania and melancholia to describe” depression, people have been attempting to not only quantify the concept of depression, but to also understand and treat it (1). The passing years have seen the rise of many different explanations for depression as well as many different treatments. To this day, there is still no quantifiable cure for depression. Even though some may argue that “depression is a treatable illness,” that is unfortunately a false hope (2). The history of depression proves that despite years of research and investigation and a multitude of treatments, the cure for depression is still only a passing hope that is simply masked by current treatments that dull the symptoms of depression. In order to understand the complexity of depression, and therefore why it cannot be easily treated, it is important to first try to define the complexity that is depression. Depression has been defined in a multitude of different ways; the ancient Greeks believed depression was due to “an imbalance in the body’s four humors . with too much [black bile] resulting in a melancholic state of mind” (3). In contrast, early Christianity said that depression was to be blamed on “the devil and God’s anger for man’s suffering” (3). Towards the end of the nineteenth century however, depression was seen as either a neurological or a psychological disorder (4). -

Bipolar Disorders 100 Years After Manic-Depressive Insanity

Bipolar Disorders 100 years after manic-depressive insanity Edited by Andreas Marneros Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany and Jules Angst University Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland KLUWER ACADEMIC PUBLISHERS NEW YORK, BOSTON, DORDRECHT, LONDON, MOSCOW eBook ISBN: 0-306-47521-9 Print ISBN: 0-7923-6588-7 ©2002 Kluwer Academic Publishers New York, Boston, Dordrecht, London, Moscow Print ©2000 Kluwer Academic Publishers Dordrecht All rights reserved No part of this eBook may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, without written consent from the Publisher Created in the United States of America Visit Kluwer Online at: http://kluweronline.com and Kluwer's eBookstore at: http://ebooks.kluweronline.com Contents List of contributors ix Acknowledgements xiii Preface xv 1 Bipolar disorders: roots and evolution Andreas Marneros and Jules Angst 1 2 The soft bipolar spectrum: footnotes to Kraepelin on the interface of hypomania, temperament and depression Hagop S. Akiskal and Olavo Pinto 37 3 The mixed bipolar disorders Susan L. McElroy, Marlene P. Freeman and Hagop S. Akiskal 63 4 Rapid-cycling bipolar disorder Joseph R. Calabrese, Daniel J. Rapport, Robert L. Findling, Melvin D. Shelton and Susan E. Kimmel 89 5 Bipolar schizoaffective disorders Andreas Marneros, Arno Deister and Anke Rohde 111 6 Bipolar disorders during pregnancy, post partum and in menopause Anke Rohde and Andreas Marneros 127 7 Adolescent-onset bipolar illness Stan Kutcher 139 8 Bipolar disorder in old age Kenneth I. Shulman and Nathan Herrmann 153 9 Temperament and personality types in bipolar patients: a historical review Jules Angst 175 viii Contents 10 Interactional styles in bipolar disorder Christoph Mundt, Klaus T. -

Exploration of the Meaning of Depression Among Psychologists: a Quantitative and Qualitative Approach

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2010 Exploration of the Meaning of Depression Among Psychologists: A Quantitative and Qualitative Approach Akira Murata University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Counseling Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Murata, Akira, "Exploration of the Meaning of Depression Among Psychologists: A Quantitative and Qualitative Approach" (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 462. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/462 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. EXPLORATION OF THE MEANING OF DEPRESSION AMONG PSYCHOLOGISTS: A QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE APPROACH __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Morgridge College of Education University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Akira Murata August 2010 Advisor: Cynthia McRae ©Copyright by Akira Murata 2010 All Rights Reserved Author: Akira Murata Title: EXPLORATION OF THE MEANING OF DEPRESSION AMONG PSYCHOLOGISTS: A QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE APPROACH Advisor: Cynthia McRae Degree Date: August 2010 Abstract While depression is considered the most common mental illness regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, compared to research on the general population, depression among psychologists has received little attention. However, as they are one of the major mental health care professionals, psychologists’ mental health could greatly affect their clients’ mental health, which raises competency and ethical concerns regarding their work as clinicians. -

Ketamine and Depression: a Review Wesley C

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 33 | Issue 2 Article 6 7-1-2014 Ketamine and Depression: A Review Wesley C. Ryan University of Washington Cole J. Marta University of California, Los Angeles Ralph J. Koek University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychiatry and Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ryan, W. C., Marta, C. J., & Koek, R. J. (2014). Ryan, W. C., Marta, C. J., & Koek, R. J. (2014). Ketamine and depression: A review. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 33(2), 40–74.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 33 (2). http://dx.doi.org/ 10.24972/ijts.2014.33.2.40 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Special Topic Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ketamine and Depression: A Review Wesley C. Ryan University of Washington Seattle, WA, USA Cole J. Marta Ralph J. Koek University of California at Los Angeles University of California at Los Angeles North Hills, CA, USA North Hills, CA, USA Ketamine, via intravenous infusions, has emerged as a novel therapy for treatment-resistant depression, given rapid onset and demonstrable efficacy in both unipolar and bipolar depression. Duration of benefit, on the order of days, varies between these subtypes, but appears longer in unipolar depression. -

The History of Depression in Neuroscience

Sound Neuroscience: An Undergraduate Neuroscience Journal Volume 1 Article 4 Issue 1 Historical Perspectives in Neuroscience 5-7-2013 The iH story of Depression in Neuroscience Morgan Hellyer University of Puget Sound, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/soundneuroscience Part of the Neuroscience and Neurobiology Commons Recommended Citation Hellyer, Morgan (2013) "The iH story of Depression in Neuroscience," Sound Neuroscience: An Undergraduate Neuroscience Journal: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/soundneuroscience/vol1/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sound Neuroscience: An Undergraduate Neuroscience Journal by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hellyer: The History of Depression in Neuroscience The History of Depression in Neuroscience Morgan Hellyer It is not a far stretch to say that philosophers and scientists have been examining depression for hundreds of years. Since around 400 BC when Hippocrates began using the terms “mania and melancholia to describe” depression, people have been attempting to not only quantify the concept of depression, but to also understand and treat it (1). The passing years have seen the rise of many different explanations for depression as well as many different treatments. To this day, there is still no quantifiable cure for depression. Even though some may argue that “depression is a treatable illness,” that is unfortunately a false hope (2). The history of depression proves that despite years of research and investigation and a multitude of treatments, the cure for depression is still only a passing hope that is simply masked by current treatments that dull the symptoms of depression. -

A History of the Concept of Atypical Depression

Jonathan R. T. Davidson A History of the Concept of Atypical Depression Jonathan R. T. Davidson, M.D. The term atypical depression as a preferentially monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI)–responsive state was first introduced by West and Dally in 1959. Further characterization of this syndrome and its responsiveness to antidepressants came to occupy the attention of many psychopharmacologists for the next 30 years. Different portrayals of atypical depression have emerged, for example, nonendoge- nous depression, phobic anxiety with secondary depression, vegetative reversal, rejection-sensitivity, and depression with severe chronic pain. Consistency across or within types has been unimpressive, and no coherent single type of depression can yet be said to be “atypical.” In successfully demonstrat- ing superiority of MAOI drugs to tricyclics, the Columbia (or DSM-IV) criteria have established their utility and become widely adopted, but other criteria have also passed this test. In this “post-MAOI” era, no novel compound or group of drugs has been clearly shown to have good efficacy in atypical depression, leaving the treatment of atypical depression as an unmet need. (J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68[suppl 3]:10–15) DEVELOPING THE CONCEPT drawn from the medication after a few months of treat- OF ATYPICAL DEPRESSION ment. This observation may reflect recovery from brief episodes of depression or possibly a set of patients with The concept of atypical depression with respect to different atypical symptoms than those seen today; it is monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) was first articu- also possible that follow-up was not long enough to lated in 1959 by West and Dally1 upon recognizing a sub- observe relapses. -

A History of the Pharmacological Treatment of Bipolar Disorder

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review A History of the Pharmacological Treatment of Bipolar Disorder Francisco López-Muñoz 1,2,3,4,* ID , Winston W. Shen 5, Pilar D’Ocon 6, Alejandro Romero 7 ID and Cecilio Álamo 8 1 Faculty of Health Sciences, University Camilo José Cela, C/Castillo de Alarcón 49, 28692 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain 2 Neuropsychopharmacology Unit, Hospital 12 de Octubre Research Institute (i+12), Avda. Córdoba, s/n, 28041 Madrid, Spain 3 Portucalense Institute of Neuropsychology and Cognitive and Behavioural Neurosciences (INPP), Portucalense University, R. Dr. António Bernardino de Almeida 541, 4200-072 Porto, Portugal 4 Thematic Network for Cooperative Health Research (RETICS), Addictive Disorders Network, Health Institute Carlos III, MICINN and FEDER, 28029 Madrid, Spain 5 Departments of Psychiatry, Wan Fang Medical Center and School of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, 111 Hsin Long Road Section 3, Taipei 116, Taiwan; [email protected] 6 Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Valencia, Avda. Vicente Andrés, s/n, 46100 Burjassot, Valencia, Spain; [email protected] 7 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Complutense University, Avda. Puerta de Hierro, s/n, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 8 Department of Biomedical Sciences (Pharmacology Area), Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Alcalá, Crta. de Madrid-Barcelona, Km. 33,600, 28871 Alcalá de Henares, Madrid, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: fl[email protected] or [email protected] Received: 4 June 2018; Accepted: 13 July 2018; Published: 23 July 2018 Abstract: In this paper, the authors review the history of the pharmacological treatment of bipolar disorder, from the first nonspecific sedative agents introduced in the 19th and early 20th century, such as solanaceae alkaloids, bromides and barbiturates, to John Cade’s experiments with lithium and the beginning of the so-called “Psychopharmacological Revolution” in the 1950s. -

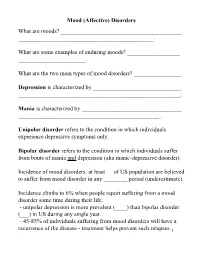

Mood (Affective) Disorders What Are Moods? ______

Mood (Affective) Disorders What are moods? _________________________________________ ______________________________________________. What are some examples of enduring moods? __________________ _______________________. What are the two main types of mood disorders? ________________ Depression is characterized by ______________________________ _______________________________________________________; Mania is characterized by __________________________________ ________________________________________________. Unipolar disorder refers to the condition in which individuals experience depressive symptoms only. Bipolar disorder refers to the condition in which individuals suffer from bouts of mania and depression (aka manic-depressive disorder). Incidence of mood disorders: at least __ of US population are believed to suffer from mood disorder in any ________ period (underestimate). Incidence climbs to 6% when people report suffering from a mood disorder some time during their life. - unipolar depression is more prevalent (____) than bipolar disorder (___) in US during any single year. - 45-85% of individuals suffering from mood disorders will have a recurrence of the disease - treatment helps prevent such relapses.1 Diagnostic criteria for Mania Criterion A - a distinct period of abnormally and persistently ______________ ____________________________. - abnormally here is defined in relation to the person’s normal behavior; - usually lasts _________________. Criterion B (requires 3 of the following symptoms, 4 if the mood is characterized as irritable): 1. __________________________________; 2. ________________________ (e.g., feels rested after only 3 hours of sleep); 3. More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking; 4. ___________ (jumping to a new line of thought before completing the preceding one) or subjective experience that thoughts are racing; 5. ___________ (i.e., attention easily drawn by unimportant stimuli); 6. Increase in goal-directed activity (socially, at work or school, or sexually) or _____________________; 7.