It All Begins with the Concept of Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

<I>Ensemble-Made Chicago</I>

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre (JADT) https://jadt.commons.gc.cuny.edu Ensemble-Made Chicago Ensemble-Made Chicago: A Guide To Devised Theater. Chloe Johnson and Coya Paz Brownrigg. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2019. Pp. 202. Chloe Johnson and Coya Paz Brownrigg’s Ensemble-Made: A Guide to Devised Theater (2019) is a valuable resource for theater educators and practitioners, particularly those who wish to deepen their knowledge of the craft variously known as devised theater, ensemble-based performance, and collective creation. Each short chapter of the book focuses on a distinct Chicago-based theater company (15 in total)—which range from large, nationally-renowned companies such as Lookingglass Theatre and The Second City to smaller, community-based collectives. Each chapter includes a brief history of the company alongside descriptions of games and exercises emblematic of their process and pedagogy. The co-written book also includes an Introduction which places the field of devising in its larger cultural and historical context, as well as a Time Line of the field and List of Exercises By Type, which function as the book’s conclusion. The authors’ methodologies are informed by their own relationship to devised theater in Chicago: Johnson is an ensemble member of the Neo-Futurists and Paz Brownrigg is the Artistic Director of Free Street Theater and cofounder of Teatro Luna—both of which are featured in the book. In this regard, they write as scholars and practitioners of devised theater but also as colleague- critics within the expansive but close-knit network of the Chicago theater community. -

CELEBRATING SIGNIFICANT CHICAGO WOMEN Park &Gardens

Chicago Women’s Chicago Women’s CELEBRATING SIGNIFICANT CHICAGO WOMEN CHICAGO SIGNIFICANT CELEBRATING Park &Gardens Park Margaret T. Burroughs Lorraine Hansberry Bertha Honoré Palmer Pearl M. Hart Frances Glessner Lee Margaret Hie Ding Lin Viola Spolin Etta Moten Barnett Maria Mangual introduction Chicago Women’s Park & Gardens honors the many local women throughout history who have made important contributions to the city, nation, and the world. This booklet contains brief introductions to 65 great Chicago women—only a fraction of the many female Chicagoans who could be added to this list. In our selection, we strived for diversity in geography, chronology, accomplishments, and ethnicity. Only women with substantial ties to the City of Chicago were considered. Many other remarkable women who are still living or who lived just outside the City are not included here but are still equally noteworthy. We encourage you to visit Chicago Women’s Park FEATURED ABOVE and Gardens, where field house exhibitry and the Maria Goeppert Mayer Helping Hands Memorial to Jane Addams honor Katherine Dunham the important legacy of Chicago women. Frances Glessner Lee Gwendolyn Brooks Maria Tallchief Paschen The Chicago star signifies women who have been honored Addie Wyatt through the naming of a public space or building. contents LEADERS & ACTIVISTS 9 Dawn Clark Netsch 20 Viola Spolin 2 Grace Abbott 10 Bertha Honoré Palmer 21 Koko Taylor 2 Jane Addams 10 Lucy Ella Gonzales Parsons 21 Lois Weisberg 2 Helen Alvarado 11 Tobey Prinz TRAILBLAZERS 3 Joan Fujisawa Arai 11 Guadalupe Reyes & INNOVATORS 3 Ida B. Wells-Barnett 12 Maria del Jesus Saucedo 3 Willie T. -

Improvisation for the Theater: a Handbook of Teaching and Directing Techniques Pdf, Epub, Ebook

IMPROVISATION FOR THE THEATER: A HANDBOOK OF TEACHING AND DIRECTING TECHNIQUES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Paul Sills, Viola Spolin | 416 pages | 28 Jul 1999 | Northwestern University Press | 9780810140080 | English | Evanston, United States Improvisation for the Theater: A Handbook of Teaching and Directing Techniques PDF Book Improvisations move through fear, boredom, laziness, and distraction to a sustained awareness of creative options. It then focuses on how we can use creativity, with a particular focus on co-creativity, to pave the way for new visions of the future and innovative solutions, and explores how storytelling can be applied to teamwork and presentations. With 53 specific, usable tools this book will improve your improv coaching, directing or teaching right away. Therefore, you will see the original copyright references, library stamps as most of these works have been housed in our most important libraries around the world , and other notations in the work. Northwestern University Press , - Performing Arts - pages. My improv training has helped me more in my life and my career than most of my formal training. Improvisation acting journal, perfect to wear to acting class at school, during acting exercises and acting games. This in-depth look at the techniques, principles, theory and ideas behind what they do is both authoritative and entertaining. Max Schaefer is a distinguished full-time teacher, actor, programmer, and president of Underdog Educational Software company. The result is both an ideas book and a fascinating exploration of the nature of spontaneous creativity. Sort order. This new edition of a highly acclaimed handbook, last published in and widely used by theater teachers and directors, is sure to be welcomed by members of the theater profession. -

Instructional Materials 2021–22

INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS 2021–22 Arithmetic A SPORK Arithmetic A, SPORK LLC Saxon Math Course 1 ISBN: 159141783X Author: Stephen Hake Title: Saxon Math Course 1 Publisher: Harcourt Achieve, Inc. & Stephen Hake Arithmetic B SPORK Arithmetic B Curriculum, SPORK LLC Civics, History, and Science Foundation • Youtube Videos (https://www.youtube.com/) • Educational Books and Children’s Literature • BrainPop Jr (https://jr.brainpop.com/) • Liberty’s Kids (DIC Entertainment Corporation) • Magic School Bus (Scholastic) Classics • Archaeology Magazine • AIRC (American Institute of Roman Culture) educational videos and other resources • Epic of Gilgamesh Code of Hammurabi • Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey The Republic (Plato) • The Politics (Aristotle) The Melian Dialogues Vergil’s Aeneid • Ovid’s Metamorphoses • The Twelve Tables • Kleiner, Fred S. 2007. A History of Roman art. Victoria: Thomson/Wadsworth Sear, Frank. 1983. Roman architecture. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. • Pedley, John Griffiths. 2007. Greek art and archaeology. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson/Prentice Hall. Connections 1 • YouTube Kids (https://youtubekids.com) • BrainPop Jr (https://jr.brainpop.com) • National Geographic for Kids (https://kids.nationalgeographic.com) Connections 2 • Scholastic (https://www.scholastic.com/home) J • ustbooksreadaloud (https://www.justbooksreadaloud.com/) • Brainpop (https://www.brainpop.com/) • Youtube (https://www.youtube.com/) • National Geographic for Kids (https://ngkidsubs.nationalgeographic.com) Engineering & Technology 1–4 • BrainPopJr: -

Student, Player, Spect-Actor: Learning from Viola Spolin and Augusto Boal: Theatre Practice As Non-Traditional Pedagogy

STUDENT, PLAYER, SPECT-ACTOR: LEARNING FROM VIOLA SPOLIN AND AUGUSTO BOAL: THEATRE PRACTICE AS NON-TRADITIONAL PEDAGOGY by EMILY GAMMON B.A., University of Maine, Orono, 2006 M.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2012 Advisor: Dr. Bud Coleman A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Theatre 2012 This thesis entitled: Student, Player, Spect-actor: Learning from Viola Spolin and Augusto Boal: Theatre Practice as Non-Traditional Pedagogy written by Emily Gammon has been approved for the Department of Theatre and Dance Bud Coleman Oliver Gerland Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Gammon, Emily (M.A., Theatre) Student, Player, Spect-actor: Learning from Viola Spolin and Augusto Boal: Theatre Practice as Non-Traditional Pedagogy Thesis directed by Dr. Bud Coleman This thesis explores the possibility that by adapting a model of disciplined improvisation, the secondary classroom will become an engaging learning environment where a wider variety of student learning preferences and styles will be honored and cultivated. I believe that effective pedagogical theory and structure aligns with that of improvisational theatre models and by examining these models more closely and by comparing them with the theories of predominant educational theorists and psychologists, we will find both commonalities and effective teaching models and strategies. The theory and practice of Viola Spolin and Augusto Boal, supported by the theory of Lev Vygotsky and of Paulo Freire, respectively, provide two examples of non - traditional pedagogy for the secondary classroom. -

One Way to Create Educational Games

International Journal of Role-Playing - Issue 6 One Way to Create Educational Games Popular abstract: Improv games, which are used to train actors in how to do improvisational theatre, may be used to train other professions as well. The games assist in the development of simple skills and also give context for the skills’ use. The director chooses a series of these quick and simple games, tailoring the games to the already existing skills of the students. The skills built through the games may assist with further exercises, which may vary widely depending on the field in which they are taught. Instructions on how to create improv games, and hazards to avoid, are also included, should a teacher or director decide to create some games. Graham MacLean [email protected] Academics often make theoretical connections serious in its potential consequences (Goffman between their own fields, such as sociology, and 1973, 17). Usually people find one or the other more theatre studies (Goffman 1979, 124). So why not take difficult. Improvising well involves cultivating a more than theoretical inspiration and take theatre range of skills to overcome this sort of difficulty training methods as well? Improv games teach how (Berger 2009, 118). When I say skills, I use the word in to socialize better through practicing aspects such its broadest definition, including a range of teachable as talking, manners, observing or listening, without behaviors as well as how to accomplish tasks. These eliminating context (Spolin 1963). As a training skills are taught together, for acting does not lend method, improv games were first designated as itself to isolating individual skills. -

Funny Feminism: Reading the Texts and Performances of Viola

FUNNY FEMINISM: READING THE TEXTS AND PERFORMANCES OF VIOLA SPOLIN, TINA FEY AND AMY POEHLER, AND AMY SCHUMER A Thesis by LYDIA KATHLEEN ABELL Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Chair of Committee, Kirsten Pullen Committee Members, James Ball Kristan Poirot Head of Department, Donnalee Dox May 2016 Major Subject: Performance Studies Copyright 2016 Lydia Kathleen Abell ABSTRACT This study examines the feminism of Viola Spolin, Tina Fey and Amy Poehler, and Amy Schumer, all of whom, in some capacity, are involved in the contemporary practice and performance of feminist comedy. Using various feminist texts as tools, the author contextually and theoretically situates the women within particular feminist ideologies, reading their texts, representations, and performances as nuanced feminist assertions. Building upon her own experiences and sensations of being a fan, the author theorizes these comedic practitioners in relation to their audiences, their fans, influencing the ways in which young feminist relate to themselves, each other, their mentors, and their role models. Their articulations, in other words, affect the ways feminism is contemporarily conceived, and sometimes, humorously and contentiously advocated. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would briefly like to thank my family, especially my mother for her unwavering support during this difficult and stressful process. Her encouragement and happiness, as always, makes everything worth doing. I would also like to thank Paul Mindup for allowing me to talk through my entire thesis with him over the phone; somehow you listening diligently and silently on the other end of the line helped everything fall into place. -

An Improv-Able Legacy: Shining the Composition Spotlight on Viola Spolin’S Improvisational Pedagogy

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2021 An Improv-able Legacy: Shining The Composition Spotlight on Viola Spolin’s Improvisational Pedagogy Cory Richard Chamberlain University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Chamberlain, Cory Richard, "An Improv-able Legacy: Shining The Composition Spotlight on Viola Spolin’s Improvisational Pedagogy" (2021). Doctoral Dissertations. 2562. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2562 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Improv-able Legacy: Shining The Composition Spotlight on Viola Spolin’s Improvisational Pedagogy By CORY CHAMBERLAIN BA, University of North Florida, 2012 MA, University of North Florida, 2014 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In English May 2021 Chamberlain | ii ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ©2021 Cory Chamberlain Chamberlain | iii An Improv-able Legacy: Shining The Composition Spotlight on Viola Spolin’s Improvisational Pedagogy By Cory Chamberlain This dissertation has been examined and approved. Dissertation Director, Dr. Cristy Beemer, Associate Professor of English Dr. Christina Ortmeier-Hooper, Associate Professor of English Dr. Alecia Magnifico, Associate Professor of English Deborah Kinghorn, Professor Emeritus of Theatre and Dance Dr. James Webber, Associate Professor of English, University of Nevada-Reno 3/4/2021 Date Approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

The Second City: Notes on Chicago's Funny Urbanism

The Second City: Notes on Chicago’s Funny Urbanism The story is of how the city of Chicago provided the ground for the development of a style of improvisational comedy, making it a setting, but also a seedbed; the fertile ground for a creative explosion. This is an urban study as cultural history, and also as performance. JOHN MCMORROUGH Cities are funny things, both equation and caprice, they are testaments to, and University of Michigan limit cases of, “big plans,” and nowhere more so than Chicago. Chicago is the Magnificent Mile, the South Side, and the Loop; it is also the ‘Windy City,’ the JULIA MCMORROUGH ‘City of Broad Shoulders,’ and the ‘Second City.’ “Come and show me another city University of Michigan with lifted head singing so proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning.” Published one hundred years ago, this line from Carl Sandburg’s seminal poem “Chicago” speaks to the unique character of the city, borne of equal parts opti- mism and effort. Chicago, like all cities, is a combination of circumstantial facts (the quantities and dispositions of its urban form) and a projective imagination (how it is seen and understood). In Chicago these combinations have been par- ticularly colored by the city’s status as an economic capital; its history is one of money and power, its form one of hyperbolic extrapolation. Whether revers- ing the flow of the Chicago River in 1900, or raising the mean level of the city by physically lifting buildings six feet in the 1850s, Chicago’s answer to the question of what the city is, has always been, in a manner of speaking, funny (both peculiar and amusing). -

Chicken Little Study Guide Summer 2021

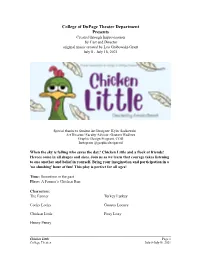

College of DuPage Theater Department Presents Created through Improvisation by Cast and Director original music created by Leo Grabowski-Grant July 8 - July 18, 2021 Special thanks to Student Art Designer: Kyler Sadkowski Art Director/ Faculty Advisor: Gautam Wadhwa Graphic Design Program, COD Instagram @graphicdesigncod When the sky is falling who saves the day? Chicken Little and a flock of friends! Heroes come in all shapes and sizes. Join us as we learn that courage takes listening to one another and belief in yourself. Bring your imagination and participation in a 'no shushing' hour of fun! This play is perfect for all ages! Time: Sometime in the past Place: A Farmer’s Chicken Run Characters: The Farmer Turkey Lurkey Cocky Locky Goosey Loosey Chicken Little Foxy Loxy Henny Penny ________________________________________________________________________ Chicken Little Page 1 College Theater July 8-July18, 2021 The production will have no intermission Director’s Note This production, is an authentic collaboration between many minds and developed through the improvisation and creativity of the actors themselves. After more than a year of working remotely, we were inspired by the ability to work in person with one another. The story of Chicken Little is a cautionary tale about what can happen when we are swayed into choosing which voice to follow. While there is nothing wrong in curiosity, an error in judgement may result in panic; and a manipulative leader might take advantage of those who are directed through fear. The only way to escape this end, is to act with reason and to listen reasonably to one another. -

Making Theater: Developing Plays with Young People. INSTITUTION Teachers and Writers Collaborative, New York, N.Y

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 304 728 CS 506 566 AUTHOR Kohl, Herbert R. TITLE Making Theater: Developing Plays with Young People. INSTITUTION Teachers and Writers Collaborative, New York, N.Y. REPORT NO ISBN-0-915924-17-x PUB DATE 88 NOTE 143p. AVAILABLE FROMTeachers and Writers Collaborative, 5 Union Square West, New York, NY 10003 ($11.95). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MFO1 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Acting; Class Activities; *Drama; Dramatic Play; *Dramatics; Elementary Secondary Education; Playwriting; Skits IDENTIFIERS *Childrens Theater; Improvisation ABSTRACT Intended for teachers who have no particular experience or training in teaching theater, but who have a love of theater and enjoy a good play, this book discusses making theater with children. It explores improvisation, reading and acting with scripts, adapting plays for young actors, and writing plays. The examples presented in the text are appropriate for a wide range of ages (from 5-year-olds to teenagers) and most can be modified to suit students of almost any age. Following an introduction discussing the power of illusion, chapter 1 deals with preparing to do theater. Chapter 2 deals with developing a performance; chapter 3 covers monologues and dialogues. Adapting plays for performance is the topic of chapter 4, and chapter 5 contains some concluding thoughts. Two appendixes contain scripts for two plays developed by the author and his classes: "The Four Alices and Their Sister Susie in Wonderland," and "Antigone." Selected resources are listed on the theory and practice of doing plays, sources for scenes, and Shakespeare. -

Mariachi Girl a Graduate Project Subm

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Teaching Language and Culture With a Musical Play: Mariachi Girl A graduate project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Theatre By Linda Russano December 2018 Signature Page The graduate project of Linda Russano is approved: _________________________________________ ______________ Professor Anamarie Gallardo de Dwyer Date _________________________________________ ______________ Professor Adrián Pérez Boluda, PhD Date _________________________________________ ______________ Professor Matthew Jackson, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Table of Contents Signature Page .................................................................................................................... ii Abstract ............................................................................................................................... v Section 1: Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 Childhood Play and Cultural Curiosity – A Personal Reflection .................................... 1 Mariachi Girl ................................................................................................................... 2 Personal Background and Graduate Project Methodology ............................................. 3 Classroom Experiences - Personal Reflections and Observations .............................. 5 Section 2: Learning through Drama and Theatre ...............................................................