Promoting Synergy Between Cities and Airports for Sustainable Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview and Analysis of the Impacts of Extreme Heat on the Aviation Industry

Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 2 July 2019 An Overview and Analysis of the Impacts of Extreme Heat on the Aviation Industry Brandon T. Carpenter University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Business Analytics Commons, Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Recommended Citation Carpenter, Brandon T. (2019) "An Overview and Analysis of the Impacts of Extreme Heat on the Aviation Industry," Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit/vol9/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit. An Overview and Analysis of the Impacts of Extreme Heat on the Aviation Industry Cover Page Footnote I am deeply appreciative of Dr. Mary Holcomb for her mentorship, encouragement, and advice while working on this research. Dr. Holcomb was my faculty advisor and may be contacted at [email protected] or (865) 974-1658 The research discussed in this article won First Place in the Haslam College of Business as well as the Office of Research and Engagement Silver Award during the 2018 University of Tennessee Exhibition of Undergraduate and Creative Achievement. -

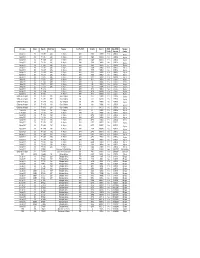

Final AFI RVSM Approvals 05 June 08

Mfr & Type Variant Reg. No. Build Year Operator Acft Op ICAO Serial No Mode S RVSM Date RVSM Operator Yes/No Approval Country Boeing 737 800 7T - VJK 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30203 0A0019 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJL 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30204 0A001A Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJM 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30205 0A001B Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJN 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30206 0A0020 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJQ 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30207 0A0021 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJP 2001 Air Algérie DAH 30208 0A0022 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJR 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30545 0A0025 Yes 01/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJS 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30210 0A0026 Yes 18/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJT 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30546 0A0027 Yes 18/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJU 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30211 0A0028 Yes 06/07/02 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJV 2005 Air Algérie DAH 0644 0A0044 Yes 31/01/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJW 2005 Air Algérie DAH 647 0A0045 Yes 05/03/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJY 2005 Air Algérie DAH 653 0A0047 Yes 20/03/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJX 2005 Air Algérie DAH 650 0A0046 Yes 20/03/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKA Air Algérie DAH 34164 0A0049 Yes 23/07/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKB Air Algérie DAH 34165 0A004A Yes 22/08/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKC Air Algérie DAH 34166 0A004B Yes 24/08/05 Algeria Gulfstream Aerospace SP 7T - VPC 2001 Gouv of Algeria IGA 1418 0A4009 Yes 27/07/05 Algeria Gulfstream Aerospace SP -

Bjets Order Release

News Release Press Contact: Andrew Broom +1.316.676.8674 [email protected] www.hawkerbeechcraft.com Hawker Beechcraft Corporation Receives Order for 20 Hawker Aircraft from Emerging Fractional and Block Charter Company SINGAPORE (Feb. 19, 2008) - Hawker Beechcraft Corporation (HBC), the world’s leading business, special-mission and trainer aircraft manufacturer, announces an order from BJETS for 20 new Hawker business jets (11 Hawker 900XP and nine 850XP jets), with options for an additional 10 aircraft. The total value of the order with options is in excess of $450 million. The aircraft will serve throughout India and Southeast Asia. BJETS is a private company that provides innovative business aviation services to corporations and high net-worth individuals in Asia. Offering their services in India and Southeast Asia, the new company is based in Mumbai, India and Singapore, with a flight operations center based in the new Hyderabad International Airport in India, and focuses on fractional, block charter and aircraft management services. Operations in India are scheduled to begin by the end of the first quarter 2008. BJETS was founded by entrepreneur Bala Ramamoothry and the Tata Group, one of India’s largest and most respected business conglomerates. Mark Baier, a well known and highly experienced leader in the business aircraft industry, will lead BJETS as CEO. “BJETS represents the entrepreneurial spirit that is prevalent in India and Southeast Asia, and we are excited that they will utilize our Hawker aircraft for -

22 the East African Directorate of Civil Aviation

NOT FOR PUBLICATION INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS B- 67 Wsshlngton, D.C. ast Africa High Commission: November 2, 195/ (22) The ast African Directorate of Civil Aviation Mr. Walter S. Roers Institute of Current World Affairs 522 Fifth Avenue New York 6, New York Dear Mr. Rogers The considerable size of Best Afr, ica, with populated centers separated by wide tracts of rugged, poorly watered country through which road and rail routes are built with difficulty and then provide only slow service, gives air transport an important position in the economy of the area. Access to ast Africa from rope and elsewhere in the world is aso greatly enhanced by air transport, which need not follow the deviating contours of the continent. Businesses with b:'enches throughout @set Africa need fast assenger services to carry executives on supervisory visits; perishable commodities, important items for repair of key machlner, and )ivestock for breeding purposes provide further traffic; and a valuable tourist traffic is much dependent upon air transport. The direction and coordination of civil aviation, to help assure the quality and amplitude of aerodromes, aeraio directiona and communications methods, and aircraft safety standards, is an important responsibility which logically fsIs under a central authority. This central authority is the Directorate of Oivil Aviation, a department of the ast Africa High Commission. The Directorate, as an interterritorlal service already in existence, came under the administration of the High Oommisslon on its effective date of inception, January I, 98, an more specifically under the Commissioner for Transport, one of the four principal executive officers of the High Commission, on May I, 199. -

Remote ID NPRM Maps out UAS Airspace Integration Plans by Charles Alcock

PUBLICATIONS Vol.49 | No.2 $9.00 FEBRUARY 2020 | ainonline.com « Joby Aviation’s S4 eVTOL aircraft took a leap forward in the race to launch commercial service with a January 15 announcement of $590 million in new investment from a group led by Japanese car maker Toyota. Joby says it will have the piloted S4 flying as part of the Uber Air air taxi network in early adopter cities before the end of 2023, but it will surely take far longer to get clearance for autonomous eVTOL operations. (Full story on page 8) People HAI’s new president takes the reins page 14 Safety 2019 was a bad year for Part 91 page 12 Part 135 FAA has stern words for BlackBird page 22 Remote ID NPRM maps out UAS airspace integration plans by Charles Alcock Stakeholders have until March 2 to com- in planned urban air mobility applications. Read Our SPECIAL REPORT ment on proposed rules intended to provide The final rule resulting from NPRM FAA- a framework for integrating unmanned air- 2019-100 is expected to require remote craft systems (UAS) into the U.S. National identification for the majority of UAS, with Airspace System. On New Year’s Eve, the exceptions to be made for some amateur- EFB Hardware Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) pub- built UAS, aircraft operated by the U.S. gov- When it comes to electronic flight lished its long-awaited notice of proposed ernment, and UAS weighing less than 0.55 bags, (EFBs), most attention focuses on rulemaking (NPRM) for remote identifica- pounds. -

Aircraft Requirements for Sustainable Regional Aviation

aerospace Article Aircraft Requirements for Sustainable Regional Aviation Dominik Eisenhut 1,*,† , Nicolas Moebs 1,† , Evert Windels 2, Dominique Bergmann 1, Ingmar Geiß 1, Ricardo Reis 3 and Andreas Strohmayer 1 1 Institute of Aircraft Design, University of Stuttgart, 70569 Stuttgart, Germany; [email protected] (N.M.); [email protected] (D.B.); [email protected] (I.G.); [email protected] (A.S.) 2 Aircraft Development and Systems Engineering (ADSE) BV, 2132 LR Hoofddorp, The Netherlands; [email protected] 3 Embraer Research and Technology Europe—Airholding S.A., 2615–315 Alverca do Ribatejo, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Recently, the new Green Deal policy initiative was presented by the European Union. The EU aims to achieve a sustainable future and be the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. It targets all of the continent’s industries, meaning aviation must contribute to these changes as well. By employing a systems engineering approach, this high-level task can be split into different levels to get from the vision to the relevant system or product itself. Part of this iterative process involves the aircraft requirements, which make the goals more achievable on the system level and allow validation of whether the designed systems fulfill these requirements. Within this work, the top-level aircraft requirements (TLARs) for a hybrid-electric regional aircraft for up to 50 passengers are presented. Apart from performance requirements, other requirements, like environmental ones, Citation: Eisenhut, D.; Moebs, N.; are also included. -

Strategies Deployed by Fly 540 Aviation Company To

STRATEGIES DEPLOYED BY FLY 540 AVIATION COMPANY TO SUSTAIN COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE BY ANN WANJIRU GUANDARU A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITED IN PARTIAL FULLFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, SCHOOL OF BUSINESS, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI 2019 DECLARATION ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT iii DEDICATION iv TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION........................................................................................................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ........................................................................................................... iii DEDICATION.............................................................................................................................. iv LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS/ACRONYMS ............................................................................. ix ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... x CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background of the Study .................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Concept of Strategy ....................................................................................... 4 1.1.2 Competitive Advantage ................................................................................. 5 1.1.3 Aviation Industry in Kenya .......................................................................... -

Make in India’ in Aviation Will Not Be Possible Without ‘Moratorium on All Taxes’

A SUPPLEMENT TO PROFILE: EMBRAER EXECUTIVE JETS P14 SP’S AVIATION 8/2017 Volume 3 • issue 3 WWW.SPS-AVIATION.COM/BIZAVINDIASUPPLEMENT PAGE 12 True ‘Make in India’ in Aviation Will Not be Possible Without ‘Moratorium on All Taxes’ EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: FACT FILE: ROHIT KAPUR, PRESIDENT, BAOA GULFSTREAM G500 P 6 P 8 REALITY AUGMENTED Experience unparalleled travel in the Gulfstream G650™. This aviation leader combines opulent cabin comforts, entertaining and business flexibility with high-speed data connectivity. Live life elevated. GULFSTREAMG650.COM +91 98 182 95755 | ROHIT KAPUR [email protected] | Gulfstream Authorized Sales Representative TOLL FREE 1800 103 2003 +65 6572 7777 | JASON AKOVENKO [email protected] | Regional Vice President CONTENTS Volume 3 • issue 3 On the cover: Government could do tremendous good by declaring a moratorium on taxes in aviation for a few years till we catch up on the lost potential. The revenues it earns from the boost in business or the national growth that the industry would bring in, would far off-set the much needed tax break. Cover Illustration by Anoop Kamath l Photograph (above) by Dassault Aviation OPERATIONS REGULATIONS SHOw repOrT 4 A Denial of Level Playing 10 Issues Affecting ‘Ease of 19 labace 2017: photo feature Field to Indian Charter Doing Aviation Business in industry India’ REGULAR DEPARTMENTS EXCLUSIVE TAXATION 2 from the editor’s desk INTERVIEW 12 True ‘Make in India’ in Aviation Will Not 3 message from president, 6 “No country can hope to be Possible Without baoa become the third largest ‘Moratorium on All Taxes’ aviation industry in 21 news at a glance the world, without the PROFILE: EMBRAER simultaneous growth of the BA industry. -

Global Volatility Steadies the Climb

WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS Global volatility steadies the climb Cirium Fleet Forecast’s latest outlook sees heady growth settling down to trend levels, with economic slowdown, rising oil prices and production rate challenges as factors Narrowbodies including A321neo will dominate deliveries over 2019-2038 Airbus DAN THISDELL & CHRIS SEYMOUR LONDON commercial jets and turboprops across most spiking above $100/barrel in mid-2014, the sectors has come down from a run of heady Brent Crude benchmark declined rapidly to a nybody who has been watching growth years, slowdown in this context should January 2016 low in the mid-$30s; the subse- the news for the past year cannot be read as a return to longer-term averages. In quent upturn peaked in the $80s a year ago. have missed some recurring head- other words, in commercial aviation, slow- Following a long dip during the second half Alines. In no particular order: US- down is still a long way from downturn. of 2018, oil has this year recovered to the China trade war, potential US-Iran hot war, And, Cirium observes, “a slowdown in high-$60s prevailing in July. US-Mexico trade tension, US-Europe trade growth rates should not be a surprise”. Eco- tension, interest rates rising, Chinese growth nomic indicators are showing “consistent de- RECESSION WORRIES stumbling, Europe facing populist backlash, cline” in all major regions, and the World What comes next is anybody’s guess, but it is longest economic recovery in history, US- Trade Organization’s global trade outlook is at worth noting that the sharp drop in prices that Canada commerce friction, bond and equity its weakest since 2010. -

A Review and Statistical Modelling of Accidental Aircraft Crashes Within Great Britain MSU/2014/07

Harpur Hill, Buxton Derbyshire, SK17 9JN T: +44 (0)1298 218000 F: +44 (0)1298 218590 W: www.hsl.gov.uk Loughborough University Loughborough Leicestershire LE11 3TU UK P: +44 (0)1509 223416 F: +44 (0)1509 223981 http://www.lboro.ac.uk/transport 12.09.2014 A Review and Statistical Modelling of Accidental Aircraft Crashes within Great Britain MSU/2014/07 HSL Report Content Loughborough University Report Content Report Approved Report Approved Andrew Curran David Pitfield for Issue By: for Issue By: Date of Issue: 12/09/2014 Date of Issue: 12/09/2014 Lead Author: Emma Tan Lead Author: David Gleave Contributing Contributing Nick Warren David Pitfield Author(s): Author(s): Technical Technical David Pitfield / Nick Warren Reviewer(s): Reviewer(s): David Gleave David Pitfield / Editorial Reviewer: Charles Oakley Editorial Reviewer: David Gleave HSL Project Loughborough PH06315 N/A Number: Project Number: HSL authored 7 ,8 ,9 Appendix (a) Loughborough 3 ,4 ,5 ,6 ,10 ,12 sections and Appendix (b) authored sections Appendix (c ) HSL/Loughborough HSL/Loughborough 1, 2, 11 1, 2, 11 Joint authorship Joint authorship 1, 2 ,7 ,8 ,9 ,11 , Loughborough HSL Quality 3 ,4 ,5 ,6 ,10 ,12 Appendix (a) and quality approved approved sections Appendix (c ) Appendix (b) sections DISTRIBUTION Matthew Lloyd-Davies Technical Customer Tim Allmark Project Officer Gary Dobbin HSL Project Manager Andrew Curran Science and Delivery Director Charles Oakley Mathematical Sciences Unit Head David Pitfield Loughborough University David Gleave Loughborough University © Crown copyright (2014) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background One of the hazards associated with nuclear facilities in the United Kingdom is accidental impact of aircraft onto the sites. -

Evaristus M. Irandu University of Nairobi Nairobi, Kenya Dawna L

Journal of Air Transportation Vol. 11, No. 1 -2006 THE DEVELOPMENT OF JOMO KENYATTA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT AS A REGIONAL AVIATION HUB Evaristus M. Irandu University of Nairobi Nairobi, Kenya Dawna L. Rhoades Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Daytona Beach, Florida ABSTRACT Air transportation plays an important role in the social and economic development of the global system and the countries that seek to participate in it. As Africa seeks to take its place in the global economy, it is increasingly looking to aviation as the primary means of connecting its people and goods with the world. It has been suggested that Africa as a continent needs to move toward a system of hubs to optimize its scarce resources. Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Nairobi, Kenya, is one of the airports in the eastern region of Africa that is seeking to fill this role. This paper discusses the prospects for success and the challenges that it will need to overcome, including projections through 2020 for the growth in passenger and cargo traffic. _____________________________________________________________________________ Evaristus M. Irandu received his Ph.D. in Transport Geography from the University of Nairobi. He is a Senior Lecturer and formerly, the Chairman of the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies in the University of Nairobi. He teaches Economic and Transport Geography, International Tourism and Tourism Management, at both undergraduate and graduate level. His research interests include: aviation planning, liberalization of air transport, non-motorized transport, urban transport, international tourism and ecotourism. His research work has appeared in several journals such as Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research and Environment and Culture. -

Analysis of Global Airline Alliances As a Strategy for International Network Development by Antonio Tugores-García

Analysis of Global Airline Alliances as a Strategy for International Network Development by Antonio Tugores-García M.S., Civil Engineering, Enginyer de Camins, Canals i Ports Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, 2008 Submitted to the MIT Engineering Systems Division and the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science in Technology and Policy and Master of Science in Aeronautics and Astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2012 © 2012 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved Signature of Author__________________________________________________________________________________ Antonio Tugores-García Department of Engineering Systems Division Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics May 14, 2012 Certified by___________________________________________________________________________________________ Peter P. Belobaba Principal Research Scientist, Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics Thesis Supervisor Accepted by__________________________________________________________________________________________ Joel P. Clark Professor of Material Systems and Engineering Systems Acting Director, Technology and Policy Program Accepted by___________________________________________________________________________________________ Eytan H. Modiano Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics Chair, Graduate Program Committee 1 2 Analysis of Global Airline Alliances as a Strategy for International Network Development by Antonio Tugores-García