An Examination of Selected Vowel Structures of Three Generations of Native Appalachian English Speakers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 English Dialect Input to the Caribbean

12 English dialect input to the Caribbean 1 Introduction There is no doubt that in the settlement of the Caribbean area by English speakers and in the rise of varieties of English there, the question of regional British input is of central importance (Rickford 1986; Harris 1986). But equally the two other sources of specific features in anglophone varieties there, early creolisation and independent developments, have been given continued attention by scholars. Opinions are still divided on the relative weight to be accorded to these sources. The purpose of the present chapter is not to offer a description of forms of English in the Caribbean – as this would lie outside the competence of the present author, see Holm (1994) for a resum´ e–b´ ut rather to present the arguments for regional British English input as the historical source of salient features of Caribbean formsofEnglish and consider these arguments in the light of recent research into both English in this region and historical varieties in the British Isles. This is done while explicitly acknowledging the role of West African input to forms of English in this region. This case has been argued eloquently and well, since at least Alleyne (1980) whose views are shared by many creolists, e.g. John Rickford. But the aim of the present volume, and specifically of the present chapter, is to consider overseas varieties of English in the light of possible continuity of input formsofEnglish from the British Isles. This concern does not seek to downplay West African input and general processes of creolisation, which of course need to be specified in detail,1 butrather tries to put the case for English input and so complement other views already available in the field. -

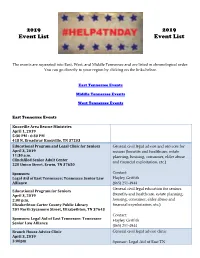

List of HELP4TN Events

2019 2019 Event List Event List The events are separated into East, West, and Middle Tennessee and are listed in chronological order. You can go directly to your region by clicking on the links below. East Tennessee Events Middle Tennessee Events West Tennessee Events East Tennessee Events Knoxville Area Rescue Ministries April 1, 2019 5:30 PM - 6:30 PM 418 N. Broadway Knoxville, TN 37203 Educational Program and Legal Clinic for Seniors General civil legal advice and services for April 3, 2019 seniors (benetits and healthcare, estate 11:30 a.m. planning, housing, consumer, elder abuse Clinchfiled Senior Adult Center and financial exploitation, etc.) 220 Union Street, Erwin, TN 37650 Sponsors: Contact: Legal Aid of East Tennessee: Tennessee Senior Law Hayley Griffith Alliance (865) 251-4944 General civil legal education for seniors Educational Program for Seniors April 3, 2019 (benefits and healthcare, estate planning, 2:00 p.m. housing, consumer, elder abuse and Elizabethton-Carter County Public Library financial expoloitation, etc.) 201 North Sycamore Street, Elizabethton, TN 37643 Contact: Sponsors: Legal Aid of East Tennessee: Tennessee Hayley Griffith Senior Law Alliance (865) 251-4944 Branch House Advice Clinic General civil legal advice clinic April 3, 2019 3:00pm Sponsor: Legal Aid of East TN Sullivan County Family Justice Center (Branch House) Contact: Christy Harris 313 Foothills Drive, Blountville TN (423) 794-2487 Good Samaritan Ministries April 6, 2019 9:00 AM - 11:00 AM 100 N Roan St Johnson City, TN 37601 Chattanooga CARES -

The Effect of Appalachian Regional Dialect on Performance Appraisal and Leadership Perceptions" (2014)

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Online Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship January 2014 The ffecE t of Appalachian Regional Dialect on Performance Appraisal and Leadership Perceptions Amie Sparks Ball Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/etd Part of the Cognitive Psychology Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Ball, Amie Sparks, "The Effect of Appalachian Regional Dialect on Performance Appraisal and Leadership Perceptions" (2014). Online Theses and Dissertations. 203. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/203 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECT OF APPALACHIAN REGIONAL DIALECT ON PERFROMANCE APPRASAL AND LEADERSHIP PERCEPTIONS By Amie Sparks Ball Master of Science Eastern Kentucky University Richmond, Kentucky 2014 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Eastern Kentucky University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 2014 Copyright © Amie Sparks Ball, 2014 All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my thesis chair, Dr. Catherine Clement, for her help and guidance. I would also like to thank my other committee members, Dr. Yoshie Nakai and Dr. Jonathan Gore, for their assistance over the past two years. I would like to express my thanks to my husband, Tyler, and my parents, John and Sheila, for their support and encouragement throughout this process. iii Abstract Speakers of Appalachian English face unique difficulties in the workplace. -

Christy Mahon Comes to Athens, Tennessee: the Playboy of the Western World in Appalachia C

Irish Studies South | Issue 2 Article 8 September 2016 Christy Mahon Comes to Athens, Tennessee: The Playboy of the Western World in Appalachia C. Austin Hill Youngstown State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/iss Part of the Celtic Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Hill, C. Austin (2016) "Christy Mahon Comes to Athens, Tennessee: The lP ayboy of the Western World in Appalachia," Irish Studies South: Iss. 2, Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/iss/vol1/iss2/8 This article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Irish Studies South by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hill: Christy Mahon Comes to Athens, Tennessee Christy Mahon Comes to Athens, Tennessee: The Playboy of the Western World in Appalachia C. Austin Hill In November 2013, I directed a production of Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World as part of the main stage season at Tennessee Wesleyan College. This production marked a number of firsts—my first production as head of the theatre program; my first production in the state of Tennessee, or indeed in the American Appalachian South; my students’ first encounter with an Irish play and playwright; and the first time in (at least) recent memory that audiences in our small town have been treated to Synge’s play. This production stayed true to Synge’s original, with the idiomatic language and Irish setting kept intact, and it sought to find cultural parallels organically.1 In keeping with this issue’s theme of exploring the Irish in the South, this paper examines the production as an instance of teaching students, audiences, and a community about Irish culture through artistic practice. -

Historical and Comparative Perspectives on A-Prefixing in the English of Appalachia

HISTORICAL AND COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVES ON A-PREFIXING IN THE ENGLISH OF APPALACHIA MICHAEL B. MONTGOMERY University of South Carolina abstract: This article both expands and confirms research on a relic grammatical feature, the prefix a- on present participles. Because previous work has concen- trated on its occurrence in the English of Appalachia and only synchronically, first its superregional distribution is shown. The article then surveys its evolution from a preposition (on or at) + gerund in Early Middle English to the prefix a- + participle. The article assesses possible transatlantic sources, arguing that southern England to be most plausible. Previous work, especially Wolfram (1980, 1988) in West Virginia and Feagin (1979) in Alabama, have identified both grammatical and phonological constraints on its occurrence and possible semantic or discourse meaning, for the prefix. These are tested against a large corpus from an area intermediate between the two, the Smoky Mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina. Four major quantita- tive constraints prohibiting the prefix, originally proposed by Wolfram, are strongly substantiated, but a small number of exceptions to each argues that they are not categorical. With respect to other, more minor patterns, the prefix in the Smoky Mountains has a different distributed from West Virginia, but overall Wolfram’s pio- neering work is corroborated. Documenting and tracking these linguistic constraints through the history of English remain tasks for future corpus linguists. A well-known feature of regional American speech, often associated with the English of Appalachia, is the syllable a- prefixed to verb present participles, as in (1) and (2): 1. Wilford was kind of sick his last years a-teaching. -

The History and Culture Of

The History and Culture of Bay Islanders and North Coast English Speakers of Honduras By Wendy Griffin © 2004 1 Table of Contents Introduction The Arrival of English Speakers in Honduras The Work of English Speakers in the 19th & 20th Centuries Their Population and Ethnic Organization Their Language and the Bilingual-Intercultural Education Project Religion and Honduran English speakers Music and Dance Clothes and Crafts Traditional Architecture of Bay Islanders and North Coast English speakers Bay Islands Oral Literature Food & Agriculture of the Bay Islanders Medicinal Plants Meat and other Protein Sources in Bay Islands Foods Land and Fishing Rights Problems Bibliography 2 Introduction In Honduras there are two Afro-Caribbean ethnic groups. One group is the Garifunas and the other is Bay Islanders or as they call themselves, the English speakers of Honduras (“los ingleses” in Spanish). Most English speakers are Black, however, there is also a number of white Bay Islanders. In Honduras the whites are called “caracoles” (Conchs). The Blacks and the Whites are often interrelated. The majority of Honduran English speakers live in the Bay Islands, but some parts of the Honduran North Coast such as La Ceiba and Puerto Cortes also have a fair number of people whose native language is English. English speakers are called “ingleses”, because their native language is English. The majority are not the descendants of the English from England. Instead the majority are descendants of people who were slaves in Jamaica, Belize, and Grand Cayman. Some English speakers were brought to Honduras as slaves, especially in the Mosquitia where slavery existed until 1843, but the overwhelming majority immigrated as free people after slavery had ended in their places of origin. -

Appalachian Dialects in the College Classroom

Appalachian Dialects in the College Classroom: Linguistic Diversity and Sensitivity in the Classroom Paper Presented at the National Conference on College Composition and Communication March 18, 2005, San Francisco, CA Felicia Mitchell Department of English Emory & Henry College P.O. Box 947 Emory, VA 24327-0947 [email protected] Mitchell 1 Abstract The purpose of this presentation is to encourage college teachers of writing, inside and outside Appalachia, to look at dialect-based errors in a more expansive way even as they help students to make better choices about standard usage. The discussion, which is presented within the context of a socio-cultural perspective on bias in perceptions of error, is intended to invite teachers to be more tolerant of diversity as they guide students to use “Standard American English.” Errors illustrating the discussion have been adapted from the writing and oral speech of students from southern Appalachia and are analyzed within the context of linguistic roots and language evolution. Linguistic analysis of errors includes the common “had went” contrasted with a more archaic yet “correct” usage, as well as nonstandard verbs and participles. Related attention is given to how oral pronunciation can invite biased perceptions of error. The presentation concludes with advice on how to be sensitive to diversity issues in the classroom. Mitchell 2 Appalachian Dialects in the College Classroom: Linguistic Diversity and Sensitivity in the Classroom You can be a little ungrammatical if you come from the right part of the country. Robert Frost . our pedagogy must reflect awareness of the conditions around us. Gail Y. Okawa When I first moved to southwest Virginia to teach at a college committed to first- generation Appalachian students, I was struck by new errors I began to hear and see. -

New Cambridge History of the English Language

New Cambridge History of the English Language Volume V: English in North America and the Caribbean Editors: Natalie Schilling (Georgetown), Derek Denis (Toronto), Raymond Hickey (Essen) I The United States 1. Language change and the history of American English (Walt Wolfram) 2. The dialectology of Anglo-American English (Natalie Schilling) 3. The roots and development of New England English (James N. Stanford) 4. The history of the Midland-Northern boundary (Matthew J. Gordon) 5. The spread of English westwards (Valerie Fridland and Tyler Kendall) 6. American English in the city (Barbara Johnstone) 7. English in the southern United States (Becky Childs and Paul E. Reed) 8. Contact forms of American English (Cristopher Font-Santiago and Joseph Salmons) African American English 9. The roots of African American English (Tracey L. Weldon) 10. The Great Migration and regional variation in the speech of African Americans (Charlie Farrington) 11. Urban African American English (Nicole Holliday) 12. A longitudinal panel survey of African American English (Patricia Cukor-Avila) Latinx English 13. Puerto Rican English in Puerto Rico and in the continental United States (Rosa E. Guzzardo Tamargo) 14. The English of Americans of Mexican and Central American heritage (Erik R. Thomas) II Canada 15. Anglophone settlement and the creation of Canadian English (Charles Boberg) NewCHEL Vol 5: English in North America and the Caribbean Page 2 of 2 16. The open-class lexis of Canadian English: History, structure, and social correlations (Stefan Dollinger) 17. Ontario English: Loyalists and beyond (Derek Denis, Bridget Jankowski and Sali A. Tagliamonte) 18. The Prairies and the West of Canada (Alex D’Arcy and Nicole Rosen) 19. -

Introduction Edited by Daniel Schreier, Peter Trudgill, Edgar W

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-71016-9 - The Lesser-Known Varieties of English: An Introduction Edited by Daniel Schreier, Peter Trudgill, Edgar W. Schneider and Jeffrey P. Williams Excerpt More information 1 Introduction DANIEL SCHREIER, PETER TRUDGILL, EDGAR W. SCHNEIDER, AND JEFFREY P. WILLIAMS The structure and use of the English language has been studied, from both synchronic and diachronic perspectives, since the sixteenth century. The result is that, today, English is probably the best researched language in the world. (Kyto,¨ Ryden´ and Smitterberg 2006: 1) Would anybody dare deny that English has been studied extremely thor- oughly? Given the fact that hundreds if not thousands of languages around the world are barely documented or simply not researched at all, the massive body of research on English seems truly without parallel, so this is strong sup- port for Kyto,¨ Ryden´ and Smitterberg’s (2006) claim. Indeed, so many studies have been carried out to enhance our knowledge of all aspects of the English language that it is impossible to attempt even a short summary here: the body of research that has been assembled over the last four centuries is substantial and constantly growing, from the treatises of orthoepists and grammarians produced throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, via English phoneticians (such as Henry Sweet) in the late nineteenth century and dialect geography in the early twentieth century, to variationist sociolinguists in the 1970s and computational linguists in the 1980sand1990s, at research centres and university institutions throughout the world, on all levels of structure and usage, phonology, syntax, lexicon and discourse, in domains as distinct as syntactic theory, psycholinguistics, language variation and change, his- torical pragmatics, etc., a list that could be continued at leisure. -

Irish English for the Non-Irish

Irish English for the non-Irish The sections of this text have been extracted largely from Raymond Hickey 2014. A Dictionary of Varieties of English. Malden, MA: Wiley- Blackwell, xxviii + 456 pages with some additions from the research website Variation and Change in Dublin English. The sections consist of (i) all definitions concerning Ireland, (ii) those involving Dublin, (iii) those involving Ulster / Northern Ireland and (iv) various entries for specific features which are particularly prevalent in Ireland. Ireland An island in north-west Europe, west of England, which consists politically of (i) the Republic of Ireland and (ii) Northern Ireland, a constituent part of the United Kingdom. The island has an area of 84,000 sq km and a total population of just under 6.5m. Geographically, the country consists of a flat central area, the Midlands, and a mountainous, jagged western seaboard and a flatter east coast with Dublin, the largest city, in the centre of the east and Belfast, the main city of Northern Ireland, in the north-east. The main ethnic groups are Irish and Ulster Scots. There speakers of Ulster English in Northern Ireland but they do not constitute a recognisable ethnic group today. TRAVELLERS are a sub-group in Irish society but do not constitute a separate ethnicity. Before the arrival of Norman and English settlers in the late twelfth century Ireland was entirely Irish-speaking. In subsequent centuries both French and English established themselves, the latter concentrated in towns on the east coast. The linguistic legacy of this is an archaic dialect area from Dublin down to Waterford. -

Non-Mainstream American English and First Grade Children's Language and Reading Skills Growth Catherine Ross Conlin

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Non-Mainstream American English and First Grade Children's Language and Reading Skills Growth Catherine Ross Conlin Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION NON-MAINSTREAM AMERICAN ENGLISH AND FIRST GRADE CHILDREN’S LANGUAGE AND READING SKILLS GROWTH By CATHERINE ROSS CONLIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Communication Disorders in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2009 Copyright © 2009 Catherine Anne Conlin All Rights Reserve The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Catherine Ross Conlin defended on May 26, 2009. __________________________________ Howard Goldstein Professor Co-Directing Dissertation __________________________________ Carol Connor Professor Co-Directing Dissertation ___________________________________ Stephanie Al Otaiba Outside Committee Member __________________________________ Shurita Thomas-Tate Committee Member Approved: ____________________________________________________ Juliann Woods, Chair, Department of Communication Disorders ____________________________________________________ Gary Heald, Dean, College of Communication The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii To my husband and son, all my love forever. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The accomplishment of this dissertation and the degree it represents have been a dream of mine for twenty five years. It would not have been possible without the tremendous support and guidance of many people. First and foremost, I owe immeasurable thanks to Carol Connor for taking me on as her doctoral student in the third year of my program. Her professionalism, compassion and genuine care and concern for me as a student were unwavering. -

The Treatment of Dialect in Appalachian Literature Chapter Author(S): Michael Ellis

University Press of Kentucky Chapter Title: The Treatment of Dialect in Appalachian Literature Chapter Author(s): Michael Ellis Book Title: Talking Appalachian Book Subtitle: Voice, Identity, and Community Book Editor(s): Amy D. Clark, Nancy M. Hayward Published by: University Press of Kentucky. (2013) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2jckk2.13 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms University Press of Kentucky is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Talking Appalachian This content downloaded from 76.77.170.243 on Tue, 14 Feb 2017 15:49:02 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Treatment of Dialect in Appalachian Literature Michael Ellis Stereotypes about Appalachian culture and Appalachian English have been around so long that it is hard to imagine a time when they did not exist, a time before there was even a distinctive variety of English in the region. Dialectologists, linguistic geographers, lexicographers, and so- ciolinguists have added considerably to our knowledge of Appalachian Englishes in the twentieth century and beyond, but how Appalachian varieties developed and what they were like in the nineteenth century are only beginning to be understood.1 However, long before the first linguistic studies were published, many Americans thought they were already familiar with the language of the southern highlands and had formed opinions about it—usually negative.