By a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

A Wearable Device to Induce and Enhance the ASMR Phenomenon for Mental Well-Being Sub Title Author Jalloul, Safa Ku

Title HESS : a wearable device to induce and enhance the ASMR phenomenon for mental well-being Sub Title Author Jalloul, Safa Kunze, Kai Publisher 慶應義塾大学大学院メディアデザイン研究科 Publication year 2018 Jtitle Abstract Notes 修士学位論文. 2018年度メディアデザイン学 第680号 Genre Thesis or Dissertation URL https://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?koara_id=KO40001001-0000201 8-0680 慶應義塾大学学術情報リポジトリ(KOARA)に掲載されているコンテンツの著作権は、それぞれの著作者、学会または出版社/発行者に帰属し、その権利は著作権法によって 保護されています。引用にあたっては、著作権法を遵守してご利用ください。 The copyrights of content available on the KeiO Associated Repository of Academic resources (KOARA) belong to the respective authors, academic societies, or publishers/issuers, and these rights are protected by the Japanese Copyright Act. When quoting the content, please follow the Japanese copyright act. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Master's Thesis Academic Year 2018 HESS: a Wearable Device to Induce and Enhance the ASMR Phenomenon for Mental Well-being Keio University Graduate School of Media Design Safa Jalloul A Master's Thesis submitted to Keio University Graduate School of Media Design in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Media Design Safa Jalloul Master's Thesis Advisory Committee: Associate Professor Kai Kunze (Main Research Supervisor) Professor Matthew Waldman (Sub Research Supervisor) Master's Thesis Review Committee: Associate Professor Kai Kunze (Chair) Professor Matthew Waldman (Co-Reviewer) Professor Keiko Okawa (Co-Reviewer) Abstract of Master's Thesis of Academic Year 2018 HESS: a Wearable Device to Induce and Enhance the ASMR Phenomenon for Mental Well-being Category: Design Summary In our fast-paced society, stress and anxiety have become increasingly common. The ability to find coping mechanisms becomes essential to reach a healthy mental condition. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

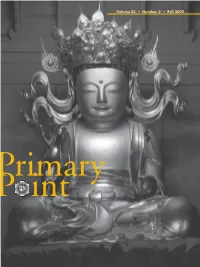

Volume 23 • Number 2 • Fall 2005

Volume 23 • Number 2 • Fall 2005 Primary Point Primary Point 99 Pound Road, Cumberland RI 02864-2726 U.S.A. Telephone 401/658-1476 • Fax 401/658-1188 www.kwanumzen.org • [email protected] online archives www.kwanumzen.org/primarypoint Published by the Kwan Um School of Zen, a nonprofit religious corporation. The founder, Zen Master Seung Sahn, 78th Patriarch in the Korean Chogye order, was the first Korean Zen Master to live and teach in the West. In 1972, after teaching in Korea and Japan for many years, he founded the Kwan Um sangha, which today has affiliated groups around the world. He gave transmission to Zen Masters, and “inka”—teaching authority—to senior students called Ji Do Poep Sa Nims, “dharma masters.” The Kwan Um School of Zen supports the worldwide teaching schedule of the Zen Masters and Ji Do Poep Sa Nims, assists the member Zen centers and groups in their growth, issues publications In this issue on contemporary Zen practice, and supports dialogue among religions. If you would like to become a member of the School and receive Let’s Spread the Dharma Together Primary Point, see page 29. The circulation is 5000 copies. Seong Dam Sunim ............................................................3 The views expressed in Primary Point are not necessarily those of this journal or the Kwan Um School of Zen. Transmission Ceremony for Zen Master Bon Yo ..............5 © 2005 Kwan Um School of Zen Founding Teacher In Memory of Zen Master Seung Sahn Zen Master Seung Sahn No Birthday, No Deathday. Beep. Beep. School Zen Master Zen -

Toward the Integration of Meditation Into Higher Education: a Review of Research

Toward the Integration of Meditation into Higher Education: A Review of Research Prepared for the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society by Shauna L. Shapiro Santa Clara University Kirk Warren Brown Virginia Commonwealth University John A. Astin California Pacific Medical Center Supplemental research and editing: Maia Duerr, Five Directions Consulting October 2008 2 Abstract There is growing interest in the integration of meditation into higher education (Bush, 2006). This paper reviews empirical evidence related to the use of meditation to facilitate the achievement of traditional educational goals, to help support student mental health under academic stress, and to enhance education of the “whole person.” Drawing on four decades of research conducted with two primary forms of meditation, we demonstrate how these practices may help to foster important cognitive skills of attention and information processing, as well as help to build stress resilience and adaptive interpersonal capacities. This paper also offers directions for future research, highlighting the importance of theory-based investigations, increased methodological rigor, expansion of the scope of education-related outcomes studied, and the study of best practices for teaching meditation in educational settings. 3 Meditation and Higher Education: Key Research Findings Cognitive and Academic Performance • Mindfulness meditation may improve ability to maintain preparedness and orient attention. • Mindfulness meditation may improve ability to process information quickly and accurately. • Concentration-based meditation, practiced over a long-term, may have a positive impact on academic achievement. Mental Health and Psychological Well-Being • Mindfulness meditation may decrease stress, anxiety, and depression. • Mindfulness meditation supports better regulation of emotional reactions and the cultivation of positive psychological states. -

Eastern and Western Contributions to «Contemplative Science»

Enrahonar. Quaderns de Filosofia 47, 2011 93-104 Eastern and Western contributions to «contemplative science» Stephen J. Laumakis University of St. Thomas Saint Paul, MN 55105 [email protected] Abstract Even the most casual survey of the various professional journal articles and books dedicated to the study of the nature, value, use, and benefits of meditation, in general, as well as the emerging field of the scientific study of contemplation reveals that this is one of the most active and promising arenas in the comparative study of Eastern and Western thought and practice. Yet, even though there are many facets of meditative practices that are common to both traditions, the contemporary Western tradition may be distinguished, in one way, from its Eastern counterpart by its current and ongoing collaboration with both the hard sciences and the social sciences. Recently, however, this openness to cooperation and work- ing with the sciences has begun to spread to Eastern practitioners. In fact, Buddhist scholar B. Alan Wallace observes in Contemplative Science, «[...] there are [...] historical roots to the principles of contemplation and of science that suggest a possible reconciliation and even integration between the two approaches». Assuming, for the sake of argument, that Wallace is correct about this, the purpose of this paper is to offer an analysis and critique of the speculative/theoretical and practical/ scientific possibilities of «contemplative science» and the unique contributions of both the Eastern and Western traditions -

See Last Page

CORRECTED APRIL 24, 2010; SEE LAST PAGE Psychotherapy Theory, Research, Practice, Training © 2010 American Psychological Association 2010, Vol. 47, No. 1, 83–97 0033-3204/10/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0018842 PSYCHOTHERAPIST MINDFULNESS AND THE PSYCHOTHERAPY PROCESS NOAH G. BRUCE, RACHEL MANBER, SHAUNA L. SHAPIRO, AND MICHAEL J. CONSTANTINO Oakland Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, Oakland Medical Center, Oakland, California A psychotherapist’s ability to relate to therapists to develop quality relationships with his or her patients is essential for de- patients (e.g., Castonguay, Constantino, & Holt- creasing patient suffering and promot- forth, 2006). Instead, psychotherapy researchers have directed most of their energies toward dis- ing patient growth. However, the psy- cerning which psychotherapeutic techniques are chotherapy field has identified few most effective for alleviating specific symptoms effective means for training psychother- (e.g., Lambert & Ogles, 2004; Roth & Fonagy, apists in this ability. In this conceptual 2005). As we address this imbalance, the goal of article, we propose that mindfulness the present conceptual article is to promote a practice may be a means for training dialogue about the role that a psychotherapist’s mindfulness plays in the psychotherapy process, psychotherapists to better relate to their specifically in the development of the patients. We posit that mindfulness is a psychotherapist–patient relationship. We propose means of self-attunement that increases that a psychotherapist’s ability to be mindful one’s ability to attune to others (in this (psychotherapist mindfulness) positively impacts case, patients) and that this interper- his or her ability to relate to patients. We posit sonal attunement ultimately helps pa- that mindfulness may be a method for developing and optimizing clinically beneficial relational tients achieve greater self-attunement qualities in a psychotherapist such as empathy, that, in turn, fosters decreased symptom openness, acceptance, and compassion. -

PPSI 2003 Schedule

Positive Psychology Summer Institute 2003 Schedule Updated July 28, 2003 All presentations will be in the Dilwyne Barn conference room (the Barn). The conference room is available for our use every day until 10:00pm. Following is information on the catered meals for the entire group: • The opening dinner will be Friday at 6:30 pm in Crow’s Nest, which is the private dining room above Krazy Kat’s Restaurant. Dr. Seligman’s presentation will start about 7:30 pm. • Breakfast will be served for our group in Crow’s Nest from Saturday through Tuesday, 7:30 am to 9:00 am. • The Saturday buffet lunch will be in the conference room at 12:15 pm • The Sunday box lunch will be in the conference room at 12:00 pm • The closing dinner will be Tuesday at 7:00 pm in Crow’s Nest OVERVIEW: Fri. 8/1 Saturday 8/2 Sunday 8/3 Monday 8/4 Tuesday 8/5 Morning Finkel, Sbarra, Robles, Workshop 2: Curhan, Guest, Ho, Greene, Schwartz Meditation, Rozin Haidt, Ryan Lucas, Tamir, Heimpel, Updegraff Lunch Buffet Lunch & Box Lunch With Faculty, With Faculty, Faculty Tables or on own or on own Afternoon Arrive Christensen, Ready, Lyubomirsky Baumeister, Kuo, Open Session 5:00: Haidt LaGuardia, Gillath, Flouri Shapiro, Carson, Workshop 3 Free Time & Gable Free Time Evening Opening Dinner/Workshop 1: Dinner in Dinner with Closing Banquet, Social Connectedness, or Philadelphia, or Faculty, or on own Discussion, Seligman Dinner on Own on own Closing Patio Discussion: Wisdom Patio Discussion Patio Discussion Banquet Friday 8/1 Speaker/Activity Until 5:00 Check in to your room 5:00-5:15 Welcome: Jon & Shelly, in the Conference Room 5:15–6:30 Faculty Talk, Shelly Gable: What Do We Do When Things Go Right? Capitalizing on Positive Events 6:30-8:00 Opening Banquet in Crow’s Nest (Above Krazy Kat’s Restaurant) Faculty Attending: Seligman, Schwartz, Lyubomirsky, Gable, Haidt 7:30-9:00 Martin Seligman Presentation: Positive Psychology: The State of the Science Sat. -

Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women

University of San Diego Digital USD Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship Department of Theology and Religious Studies 2019 Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women Karma Lekshe Tsomo PhD University of San Diego, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Digital USD Citation Tsomo, Karma Lekshe PhD, "Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women" (2019). Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship. 25. https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Section Titles Placed Here | I Out of the Shadows Socially Engaged Buddhist Women Edited by Karma Lekshe Tsomo SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU First Edition: Sri Satguru Publications 2006 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2019 Copyright © 2019 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover design Copyright © 2006 Allen Wynar Sakyadhita Conference Poster -

The Compass of Zen (Shambhala Dragon Editions) Online

oDFsk [Read ebook] The Compass of Zen (Shambhala Dragon Editions) Online [oDFsk.ebook] The Compass of Zen (Shambhala Dragon Editions) Pdf Free Seung Sahn *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #570817 in eBooks 1997-10-28 1997-10-28File Name: B009GN3E5K | File size: 79.Mb Seung Sahn : The Compass of Zen (Shambhala Dragon Editions) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Compass of Zen (Shambhala Dragon Editions): 2 of 3 people found the following review helpful. Will Change Your Life.By Will CorsairA student in a class I was teaching told me about this book. He's from Korea originally, and is part of a Zen group in, of all places, Oklahoma City.The author is a Zen master from Korea, and he writes with a direct, light-hearted style that is clear and not at all intimidating or overwhelming. I found myself very drawn to what he was offering.The book is a transcription of his many Dharma talks, so the text is sometimes a bit choppy. However, that doesn't detract from how well the book is put together. It will change the way you see the world and maybe how you live your life.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Best basic Buddhism book I have read.By Jeffrey BordelonReally clear essentiAl understanding. New words. Great the sky is blue. The trees are green. Woof. Woof. Don't know mind.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. -

THE LIFE and TIMES of ÑANAVIRA THERA by Craig S

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF ÑANAVIRA THERA By Craig S. Shoemake Who Was the Venerable Ñanavira Thera? He was born Harold Edward Musson on January 5, 1920 in the Aldershot military barracks near Alton, a small, sleepy English town in the Hampshire downs an hour from London. His father, Edward Lionel Musson, held the rank of Captain of the First Manchester Regiment stationed at Aldershot’s Salamanca Barracks. A career officer, Edward Musson later attained the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and probably expected his son and only child to follow in his footsteps. His wife, nee Laura Emily Mateer, was Harold’s devoted mother. The family was quite wealthy, with extensive coalmine holdings in Wales. Much of Harold’s youth was spent at a mansion on the outskirt of Alton, within sight of a Benedictine abbey. Townspeople describe the boy as solitary and reflective; one remembered Harold saying that he enjoyed walking alone in the London fogs. The same neighbor recalled Harold’s distaste for a tiger skin displayed in the foyer of the family’s residence, a trophy from one of his father’s hunts in India or Burma. Between 1927 and 1929 the family was stationed in Burma, in Rangoon, Port Blair, and Maymo, and this experience afforded young Harold his first glimpse of representatives of the way of life he would later adopt: Buddhist monks. In a conversation with interviewer Robin Maugham (the nephew of novelist Somerset Maugham), Harold (by then the Venerable Ñanavira) indicated that what he saw in Burma as a child deeply affected him: “I suppose that my first recollection of Buddhism was when I joined my father in Burma. -

Engaged Buddhism

Buddhism Buddhism and Social Action: Engaged Buddhism Buddhism and Social Action: Engaged Buddhism Summary: Pioneered by the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh in the 1970s, “Engaged Buddhism” brings a Buddhist perspective to the ongoing struggle for social and environmental justice in America. Some observers may associate Buddhism, and especially Buddhist meditation, with turning inward away from the world. However, many argue that the Buddhist tradition, with its emphasis on seeing clearly into the nature of suffering and, thus, cultivating compassion, has a strong impetus for active involvement in the world’s struggles. This activist stream of Buddhism came to be called “Engaged Buddhism”— Buddhism energetically engaged with social concerns. Among the first to speak of Engaged Buddhism in the United States was the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh. Hanh came to the United States during the Vietnam War to explain the meaning of Buddhist-led protests and demonstrations against the American-supported Saigon government and to offer a peace proposal. In 1978, the Buddhist Peace Fellowship, inspired by the work of Thich Nhat Hanh, was formed to extend the network of Buddhist peace workers to include people from all Buddhist streams. Today, the network is both national and international and aims to address issues of peace, the environment, and social justice from the standpoint of Buddhist practice as a way of peace. In the United States, the Buddhist Peace Fellowship has involved Buddhists in anti-nuclear campaigns, prison reform, and saving ancient forests. The American development of Engaged Buddhism has a multitude of examples and expressions. Many Buddhist-inspired and led programs are at the forefront of hospice care for the dying.