'It's All About Jesus'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journey Through Mark Retreat COVID A

The Path For The Journey Gospel of Mark Overview by The Bible Project Mark 1 • Here for You, Matt Redman Mark 2 • Still, Rend Collective A Journey Into Mark Mark 3 • Jesus, There’s No One Like You, Sovereign Grace Music Mark 4 • Word of God Speak, Mercy Me Mark 5 • Holy Ground, Melodie Malone Mark 6 • Dancing on the Waves, We the Kingdom Mark 7 • The Heart of Worship, Matt Redman Mark 8 • Here I Am to Worship, Tim Hughes Mark 9 • Build My Life, Pat Barrett Mark 10 • Kyrie Eleison, Chris Tomlin Mark 11 • Hosanna, Israel Houghton Mark 12 • Here’s My Heart, Crowder Mark 13 • Look Upon the Lord, Paul Baloche Mark 14 • Alabaster, Rend Collective Mark 15 • O, Come to the Altar, Elevation Mark 16 • Overwhelmed, Big Daddy Weave Reminder: Each chapter has been paired with a worship song which can be found on the Christ As A Disciple Church US YouTube channel under playlists: Gospel of Mark Retreat. “Come follow me,” Jesus said. - Mark 1:17a A Journey Into Mark As A Disciple 2. Read: Enter into the Scriptures through your imagination. Place yourself on the scene and read from Goal the perspective of someone “who was there.” What is To create a rhythm during this unique time which enables Jesus asking of me and challenging me to do? you, as a disciple of Jesus, to create space for the active 3. Reflect: Use the following questions to guide you on presence of Christ in the everyday moments of your life. reflecting on the day’s chapter. -

Mediator Volume 3 Issue 1 October 2001

A VERY LOUD QUIET TIME A Review of SONICFLOOd by Stephen J. Bennett SONICFLOOd is a contemporary Christian band which has released one album (self-titled, by Gotee Records in 1999). The band, based in Nashville, is made up of four members: Jeff Deyo, Jason Halbert, Dwayne Laring, and Aaron Blanton.1 Their music is alternative rock with a liberal dose of strings (violins, etc.). The music is definitely guitar-driven and is often more of a “super-sonic deluge” than merely a “sonic flood.” Their album is, however, designed as a praise and worship album with the result of, as one member of the band put it, a very loud quiet time. “Sonicflood” is defined on their website as follows: SONICFLOOd (‘so-nik ‘flud): noun- 1. refers to the cleansing flood that God washes over us as He gets rid of the old in us and creates the new; 2. modern rock praise and worship band on Gotee Records, continuing to remain on the cutting edge of the youth praise and worship movement in the United States.2 The name of the band comes from Revelation 19:6 which refers to the praise of a multitude which sounded “like the roar of rushing waters 1The lineup has changed since their album was recorded (see http://www.sonicflood.com) but the original members were scheduled to release a new album. 2http://www.sonicflood.com/textonly.html#bio 148 Reviews 149 and like loud peals of thunder”3 (NIV). The writer of these words was no doubt familiar with the Hebrew word for “multitude,” which is also used for the roaring or raging of the sea. -

Welcome to Worship February 7, 2021

Welcome to Worship February 7, 2021 GATHERING SONG “You Are Good" CCLI Song #3383788 Israel Houghton © 2001 Integrity's Praise! Music VERSE 1: CHORUS: Lord You are good We worship You, Hallelujah, hallelujah And Your mercy endureth forever We worship You for who You are Lord You are good We worship You, Hallelujah, hallelujah And Your mercy endureth forever We worship You for who You are People from every nation and tongue For You are good From generation to generation WELCOME & GREETING OPENING SONG "10,000 Reasons" CCLI Song #6016351 Jonas Myrin | Matt Redman © 2011 Said And Done Music CHORUS: VERSE 2: Bless the Lord O my soul, O my soul You're rich in love and You're slow to anger Worship His holy name Your name is great and Your heart is kind Sing like never before, O my soul For all Your goodness I will keep on singing I'll worship Your holy name Ten thousand reasons for my heart to find VERSE 1: VERSE 3: The sun comes up it's a new day dawning And on that day when my strength is failing It's time to sing Your song again The end draws near and my time has come Whatever may pass and whatever lies before me Still my soul will sing Your praise unending Let me be singing when the evening comes Ten thousand years and then forevermore OPENING PRAYER Sing CHORUS after prayer CHILDREN'S MESSAGE GOSPEL ACCLAMATION “Your Word” CCLI Song #7068426 Chris Davenport © 2016 Hillsong Music Publishing Australia VERSE: CHORUS: Deep calls to deep within Your presence The lamp unto my feet, The light unto my path When I hear You speak my soul awakens -

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 12 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 12:00:10 AM Hold Me Jesus Big Daddy Weave Every Time I Breathe (2006) 12:03:59 AM Do Something Matthew West Into The Light 12:07:59 AM Wonderful Merciful Savior Selah Press On (2001) 12:12:20 AM Jesus Loves Me Chris Tomlin Love Ran Red (2014) 12:15:45 AM Crown Him With Many Crowns Michael W. Smith/Anointed I'll Lead You Home (1995) 12:21:51 AM Gloria Todd Agnew Need (2009) 12:24:36 AM Glory Phil Wickham The Ascension (2013) 12:27:47 AM Do Everything Steven Curtis Chapman Do Everything (2011) 12:31:29 AM O Love Of God Laura Story God Of Every Story (2013) 12:34:26 AM Hear My Worship Jaime Jamgochian Reason To Live (2006) 12:37:45 AM Broken Together Casting Crowns Thrive (2014) 12:42:04 AM Love Has Come Mark Schultz Come Alive (2009) 12:45:49 AM Reach Beyond Phil Stacey/Chris August Single (2015) 12:51:46 AM He Knows Your Name Denver & the Mile High Orches EP 12:55:16 AM More Than Conquerors Rend Collective The Art Of Celebration (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 1 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 1:00:08 AM You Are My All In All Nichole Nordeman WOW Worship: Yellow (2003) 1:03:59 AM How Can It Be Lauren Daigle How Can It Be (2014) 1:08:12 AM Truth Calvin Nowell Start Somewhere 1:11:57 AM The One Aaron Shust Morning Rises (2013) 1:15:52 AM Great Is Thy Faithfulness Avalon Faith: A Hymns Collection (2006) 1:21:50 AM Beyond Me Toby Mac TBA (2015) 1:25:02 AM Jesus, You Are Beautiful Cece Winans Throne Room 1:29:53 AM No Turning Back Brandon Heath TBA (2015) 1:32:59 AM My God Point of Grace Steady On 1:37:28 AM Let Them See You JJ Weeks Band All Over The World (2009) 1:40:46 AM Yours Steven Curtis Chapman This Moment 1:45:28 AM Burn Bright Natalie Grant Hurricane (2013) 1:51:42 AM Indescribable Chris Tomlin Arriving (2004) 1:55:27 AM Made New Lincoln Brewster Oxygen (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 2 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 2:00:09 AM Beautiful MercyMe The Generous Mr. -

American Prodigal Tour 3.0” Beginning March 1

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THREE TIME GRAMMY® NOMINATED CROWDER ANNOUNCES HIS “AMERICAN PRODIGAL TOUR 3.0” BEGINNING MARCH 1 TICKETS ON SALE NOW TO SEE CROWDER LIVE ONSTAGE WITH SPECIAL GUEST THE YOUNG ESCAPE Nashville, Tenn (February 2018)—Three time GRAMMY® nominated artist CROWDER announces his 25-city “American Prodigal Tour 3.0,” which will begin on March 1 and run through April 22. The tour will feature special guest, The Young Escape. Tickets are on sale today. CROWDER’s “American Prodigal Tour 3.0” will feature live performances from his current chart-topping album, AMERICAN PRODIGAL, which debuted at #5 on Billboard’s Top Albums chart, #12 on Billboard’s Top 200 chart, #3 on the Digital Albums chart, and #1 on the Christian & Gospel Album chart. AMERICAN PRODIGAL’s lead single, “Run Devil Run,” was picked up by NBC’s “Sunday Night Football,” and hit #6 on the Christian Digital Songs chart. AMERICAN PRODIGAL also scored Top 10 radio hits with the K-LOVE Fan Award nominated “My Victory” and “Forgiven.” His current single “All My Hope” adds to the string of hits, as it is Top 10 and continuing to quickly climb the charts. Over the past two decades, David Crowder has transcended the usual boundaries associated with gospel music with lyrically powerful, musically intricate and unpredictable songs that have been sung and played everywhere from churches, to mainstream clubs across the country. Since the 2012 conclusion of his eight-time GMA Dove Award winning and GRAMMY® nominated David Crowder Band, the ever-evolving singer-songwriter has been on a fresh creative, critical and commercial roll, recording two hit crossover albums and a batch of hit singles as a solo artist. -

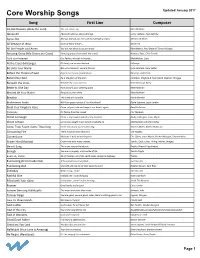

Core Worship Songs Updated January 2017 Song First Line Composer

Core Worship Songs Updated January 2017 Song First Line Composer 10,000 Reasons (Bless the Lord) The sun comes up, Matt Redman Above All Above all nations, above all kings Lenny LeBlanc, Paul Baloche Agnus Dei Alleluia, alleluia, for the Lord God Almighty reigns Michael W Smith All because of Jesus Giver of every breath… Steve Fee All the People said Amen You are not alone if you are lonely Matt Maher, Paul Moak & Trevor Morgan Amazing Grace (My Chains are Gone) Amazing grace, how sweet the sound Newton, Rees, Chris Tomlin As it is in heaven Our Father, who art in heaven… Matt Maher, Cash At the Cross (Hillsongs) Oh Lord, you've searched me Hillsongs Be Unto Your Name We are a moment, you are forever Lynn DeShazo, Gary Sadler Before the Throne of God Before the throne of God above Bancroft, Vicki Cook Behold Our God He is the glory of the stars Jonathan, Meghan & Ryan Baird, Stephen Altrogge Beneath the Cross Beneath the cross of Jesus Keith & Kristyn Getty Better Is One Day How lovely is your dwelling place Matt Redman Blessed Be Your Name Blessed be your name Matt Redman Breathe This is the air I breathe Marie Barnett Brokenness Aside Will Your grace run out if I let You down? David Leonard, Leslie Jordan Build Your Kingdom Here Come set your rule and reign in our hearts again Rend Collective Cannons It's falling from the clouds Phil Wyckam Christ is Enough Christ is my reward and all of my devotion Reuben Morgan, Jonas Myrin Christ is Risen Let no one caught in sin remain insidethe lie Matt Maher and Mia Fieldes Come Thou Fount, Come -

New from Hillsong! New Release!

pg0144v2_Layout 1 3/30/2018 3:44 PM Page 45 40th Anniversary Spring/Summer 2018 New Release! NEW CD by Smitty on back cover and backlist on pages 2 & 3 $ Deal!5 page 2 New from Hillsong! page 6 More than 15,000 albums and 215,000 downloads available at Christianbook.com! page 7 1–800–CHRISTIAN (1-800-247-4784) pg0203_Layout 1 3/30/2018 3:40 PM Page 2 Price good Deal! through 5/31/18, then $9.99! Paul Baloche: Ultimate Collection For three decades, Baloche has helped believers world- wide praise the “King of Heav- en.” Worship along with “Open the Eyes of My Heart,” “Glori- ous,” “Offering,” “Above All,” “My Hope,” and more. UECD71072 Retail $13.99 . .CBD $7.99 NEW! NEW! Country Faith Love Songs Celebrate love with some of the biggest names in country music! Enjoy “Thank You” (Keith Ur- ban); “Don’t Take the Girl” (Tim McGraw); “When I’m Gone” (Joey & Rory); and more. UECD83315 Retail $13.98 . .CBD $11.99 Michael W. Smith Surrounded A brand-new soul-stirring offering to the worldwide church! This Table of Contents powerful live recording includes “Your House”; “Light to You”; “Reckless Accompaniment Tracks . .24–27 Love”; “Do It Again”; “Great Are You, Lord”; the title track; and more. Bargains . .3 UECD25509 Retail $13.99 . .CBD $9.79 Black Gospel . .35 Have you heard . Contemporary & Pop . .36–41 UECD16827 Decades of Worship . 11.99 9.99 UECD11535 Worship . 9.99 8.49 Favorite Artists . .42, 43 UECD9658 Worship Again . 9.99 8.99 Hymns . -

Bulletin May 23 2021

BETHANY UNITED METHODIST CHURCH Sunday, May 23, 2021 Pentecost Sunday 63rd Sunday in Covid-19 1270 Sanchez Street San Francisco, CA 94114 415-647-8393 Rev. Sadie Stone Music Director Ray Capiral Guided by God’s radical love for all, Bethany seeks to… Offer sanctuary, Inspire personal transformation, Foster a faith community, and Engage locally and globally for social justice. 1 Bethany News and Notes Sunday, May 23, 2021 Sunday, May 23, 2021 Zoom Greeter: Walter Thoma Zoom Greeter: Jeanette LaFors Digital Liturgist: Michael Eaton Digital Liturgist: Josh Webster Fellowship: Whatever is in your kitchen Fellowship: Whatever is in your kitchen Zoom Office Hours: Office hours Monday May 24th 9:30am-11am. Have a question? Want to check in? Want to chat? Stop by the zoom room anytime between 9:30-11am on Monday for my office hours. https://zoom.us/j/97919674908 PRIDE Events 2021!!! • Book Study -- Tuesday evenings at 7-8pm in June (June 8, 15, 22, 29 and July 6), for the book "Staying Awake -- the Gospel for Changemakers" by Tyler Sit. Hosted by Steve Wereb. • Reading and Discussion with author and pastor Rev. Tyler Sit, July 13 @ 6:30pm The nine chapters in the book cover nine practices that the author & his community have discovered to be the most fruitful in transforming the world and living a meaningful life. In each chapter, the book covers "the why" "the how" and some scripture/poetry for reflection, and it's easy to read. Tyler has also provided a study guide. • Gay Trivia Game Night, on Zoom, June 17 at 7pm. -

2020 SRC Music Video Playlist.Pdf

4/3/2021 VLC generated playlist Playlist 1. 10,000 Reasons (Bless the Lord) - Matt Redman (Best Worship Song Ever) (with Lyrics).mp4 ( 5:42) 2. 10000reasonsfull_480p_mov.mov ( 5:20) 3. All My Hope - Crowder (Feat. Tauren Wells) (Lyrics).mp4 ( 3:27) 4. Alone With GOD - 3 Hour Peaceful Music Relaxation Music Christian Meditation Music Prayer Music.mp4 (184: 5) 5. Andy Williams, May Each Day, with lyrics.mp4 ( 2:53) 6. At Calvary By Casting Crowns- Lyrics video.mp4 ( 4: 8) 7. Be Thou My Vision (Krauss).mp4 ( 3:30) 8. Be Thou My Vision (Studio Version w Lyrics).mp4 ( 3:13) 9. Because He Lives - David Crowder Band [Lyrics].mp4 ( 4:21) 10. Because He Lives I Can Face Tomorrow - Worship Song With Lyrics.mp4 ( 4: 2) 11. Big Daddy Weave Jesus I Believe lyric video.mp4 ( 4:35) 12. Big Daddy Weave - Jesus I Believe (Official Lyric Video).mp4 ( 4: 8) 13. Big Daddy Weave Redeemed Lyric Video.mp4 ( 4:33) 14. Blessed Assurance Lyrics.mp4 ( 4:21) 15. Blessed Assurance Christian Worship Song Lyrics.mp4 ( 4:21) 16. Broken Things - [Lyric Video] Matthew West.mp4 ( 3: 7) 17. Broken Vessels (Amazing Grace) [Official Lyric Video] - Hillsong Worship.mp4 ( 9:29) 18. Casting Crowns - God of All My Days (Official Lyric Video).mp4 ( 5: 2) 19. Casting Crowns - Just Be Held (lyrics).mp4 ( 3:41) 20. Casting Crowns - Praise You In This Storm (Official Lyric Video).mp4 ( 5: 3) 21. Casting Crowns - Who Am I (Official Lyric Video).mp4 ( 5:33) 22. Casting Crowns-Blessed Redeemer (lyrics).mp4 ( 4:13) 23. -

Youth Group @ Home Sunday 17Th May 2020

Youth group @ Home Sunday 17th May 2020 Christian Character – Session 5: Being Joyful Good morning and welcome to session 5 of Youth Group @ Home. Each week we are going to look at a different element of what builds Christian character. Last week we looked at being patient, this week we are going to explore how we can be more joyful. Why not go through today’s session with family or friends? You could always Zoom call some friends and go through the activities together. Activity Put the list below in order with what you think is most required for happiness at number 1, down to what is least required for happiness at number 10. ● money ● top job ● boyfriend/girlfriend ● feeling close to God ● fame ● dream house ● health ● a great body ● close friends Discuss the following: Why did you choose the order that you did? Is there anything else you think should have been included in your list? Are all the things on the list reliable (i.e. will they ALWAYS make you happy)? Think Do you think there is a difference between Happiness and Joy? Happiness is usually thought of as an emotion that is created purely from our physical circumstances, now God can make us happy when he changes our circumstances so that they can bring us happiness but the Bible says joyfulness is different, something that develops in us as we get closer to God (read Galatians 5:22). What do you think this means i.e. should a Christian always smile? Will someone who knows God never cry or be cross? Should they be happy when bad things happen? Although often Christians will be happy because of the circumstances that they’re in, when the Bible talks about joy, it is describing a feeling of deep spiritual contentment that comes from trusting that God knows what's going on and will look after you. -

Third Sunday in Lent

3rd SUNDAY after PENTECOST Chorus Amen, Amen I'm alive, I'm alive June 13, 2021 Because He lives Amen, Amen 10:30 am Let my song join the one that never ends Because He lives Bridge Zion Lutheran Church I can face tomorrow Because He lives 1400 South Duluth Avenue Every fear is gone I know He holds my life my future in His hands Sioux Falls, South Dakota 57105 End Chorus www.zlcsf.org zlc Sioux Falls Amen, Amen I'm alive, I'm alive Because He lives Amen, Amen Let my song join the one that never ends AS WE GATHER Amen, Amen I'm alive, I'm alive Because He lives Amen, Amen The parables of our Lord convey the mysteries of the kingdom of God to those who are Let my song join the one that never ends “able to hear it,” that is, “to his own disciples,” who are catechized to fear, love and Because He lives Because He lives trust in Him by faith (Mark 4:33–34). He scatters “seed on the ground,” which “sprouts and grows” unto life, even as “he sleeps and rises” (Mark 4:26–27). “On the mountain height of Israel,” He plants a young and tender twig, and it becomes “a noble cedar.” WELCOME AND ANNOUNCEMENTS Indeed, His own cross becomes the Tree of Life, under which “every kind of bird” will dwell, and in which “birds of every sort will nest” (Ezek. 17:22–25). His cross is our resting place, even while now in mortal bodies, we “groan, being burdened” (2 MINUTE FOR MINISTRY – Chez Shoup Corinthians 5:1–4). -

April 17, 2021

CSN Daily Playlog From: 04/17/2021 To: 04/17/2021 Mountain Time Log Date Log Time Song Artist Audio Title Play Length 04/17/2021 01:00:00 Thy Word (:04)Awesome In This Place 05:21.255 04/17/2021 01:05:22 Lex Buckley (:02)Gaze Upon Your Beauty 04:15.004 04/17/2021 01:09:37 Cathy Burton (:05)Great And Glorious 05:21.785 04/17/2021 01:15:19 Vineyard (San Luis Obispo, CA)(:07)Safe In Your Hands 04:32.661 04/17/2021 01:19:52 Vertical Worship (:03)Open Up The Heavens 04:04.097 04/17/2021 01:23:56 Sion and Shannon Alford (:03)I Will Follow 03:04.722 04/17/2021 01:30:00 Telecast (:04)Thank You 03:57.675 04/17/2021 01:33:58 Brenton Brown (:02)We Lift You Up 03:48.816 04/17/2021 01:37:47 Kate Simmonds (:10)We Come In Your Name 04:57.489 04/17/2021 01:42:52 Priscilla Miller (:03)Song Of The Redeemed 02:52.574 04/17/2021 01:45:44 Mark McCoy and Andy Park (:03)I See The Lord 05:45.739 04/17/2021 01:51:30 Paradise (:03)Jesus Saviour 05:30.380 04/17/2021 02:00:00 Andy Park (:03)Who Is Like You 03:28.956 04/17/2021 02:03:29 Matt Redman (:02)10,000 Reasons 04:50.927 04/17/2021 02:08:20 Abundant Life (:03)It's You 04:29.160 04/17/2021 02:12:53 James & Rebekah Caggegi (:03)The Way 03:57.972 04/17/2021 02:16:51 Steve Jones (:03)Saving Grace 04:35.176 04/17/2021 02:21:26 Matt Redman (:03)Here For You 05:34.599 04/17/2021 02:30:01 Kingsway Music (:04)Most Holy Father (I Believe03:29.238 In You) 04/17/2021 02:33:30 Tim Hughes (:03)At Your Name (Forever) 06:11.552 04/17/2021 02:39:42 Heather Clark Band (:03)Come In 03:49.363 04/17/2021 02:43:59 Jeremey Ellis