From Path to Portage: Issues of Scales, Process, and Pattern in Understanding New Brunswick Riverine Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AT a GLANCE 2017 Oromocto, Gagetown, Fredericton Junction Area This Community Is 1 of 33 in New Brunswick

MY COMMUNITY AT A GLANCE 2017 Oromocto, Gagetown, Fredericton Junction Area This community is 1 of 33 in New Brunswick. Population: 18,427 Land Area (km2): 1,325 It is part of: The goal of My Community at a Glance is to empower Zone 3: Fredericton and River individuals and groups with information about our Valley Area communities and stimulate interest in building healthier communities. It can help us towards becoming increasingly engaged healthier New Brunswickers. The information provided in this profile gives a comprehensive view about the people who live, learn, work, take part in activities and in community life in this area. The information included in this profile comes from a variety of provincial and federal sources, from either surveys or administrative databases. Having the ability to access local information relating to children, youth, adults and seniors for a community is important to support planning and targeted strategies but more importantly it can build on the diversity and uniqueness of each community. The median household income is The main industries include: $65,082 Public administration Retail trade Health care and social assistance Accommodation and food services Construction See their health as being very good or excellent (%) 58 57 35 Youth of grade 6 to 12 Adults (18 to 64 years) Seniors (65 years and over) My Community About the New Brunswick Health Council: New Brunswickers have a right to be aware of the decisions The communities in this profile include: being made, to be part of the decision making process, and to be Blissville aware of the outcomes and cost of the health system. -

The Siege of Fort Beauséjour by Chris M. Hand Notes

1 The Siege of Fort Beauséjour by Chris M. Hand Notes Early Conflict in Nova Scotia 1604-1749. By the end of the 1600’s the area was decidedly French. 1713 Treaty of Utrecht After nearly 25 years of continuous war, France ceded Acadia to Britain. French and English disagreed over what actually made up Acadia. The British claimed all of Acadia, the current province of New Brunswick and parts of the current state of Maine. The French conceded Nova Scotia proper but refused to concede what is now New Brunswick and northern Maine, as well as modern Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton. They also chose to limit British ownership along the Chignecto Isthmus and also harboured ambitions to win back the peninsula and most of the Acadian settlers who, after 1713, became subjects of the British Crown. The defacto frontier lay along the Chignecto Isthmus which separates the Bay of Fundy from the Northumberland Strait on the north. Without the Isthmus and the river system to the west, France’s greatest colony along the St. Lawrence River would be completely cut off from November to April. Chignecto was the halfway house between Quebec and Louisbourg. 1721 Paul Mascarene, British governor of Nova Scotia, suggested that a small fort could be built on the neck with a garrison of 150 men. a) one atthe ridge of land at the Acadian town of Beaubassin (now Fort Lawrence) or b) one more west on the more prominent Beauséjour ridge. This never happened because British were busy fighting Mi’kmaq who were incited and abetted by the French. -

KENNEBEC SALMON RESTORATION: Innovation to Improve the Odds

FALL/ WINTER 2015 THE NEWSLETTER OF MAINE RIVERS KENNEBEC SALMON RESTORATION: Innovation to Improve the Odds Walking thigh-deep into a cold stream in January in Maine? The idea takes a little getting used to, but Paul Christman doesn’t have a hard time finding volunteers to do just that to help with salmon egg planting. Christman is a scientist with Maine Department of Marine Resource. His work, patterned on similar efforts in Alaska, involves taking fertilized salmon eggs from a hatchery and planting them directly into the cold gravel of the best stream habitat throughout the Sandy River, a Kennebec tributary northwest of Waterville. Yes, egg planting takes place in the winter. For Maine Rivers board member Sam Day plants salmon eggs in a tributary of the Sandy River more than a decade Paul has brought staff and water, Paul and crews mimic what female salmon volunteers out on snowshoes and ATVs, and with do: Create a nest or “redd” in the gravel of a river waders and neoprene gloves for this remarkable or stream where she plants her eggs in the fall, undertaking. Finding stretches of open stream continued on page 2 PROGRESS TO UNDERSTAND THE HEALTH OF THE ST. JOHN RIVER The waters of the St. John River flow from their headwaters in Maine to the Bay of Fundy, and for many miles serve as the boundary between Maine and Quebec. Waters of the St. John also flow over the Mactaquac Dam, erected in 1968, which currently produces a substantial amount of power for New Brunswick. Efforts are underway now to evaluate the future of the Mactaquac Dam because its mechanical structure is expected to reach the end of its service life by 2030 due to problems with the concrete portions of the dam’s station. -

Contaminant Assessment of Coastal Bald Eagles at Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge and Acadia National Park

SPECIAL PROJECT REPORT FY12‐MEFO‐2‐EC Maine Field Office – Ecological Services September 2013 Contaminant Assessment of Coastal Bald Eagles at Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge and Acadia National Park Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of the Interior Mission Statement U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Our mission is working with others to conserve, protect, and enhance the nation’s fish and wildlife and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people. Suggested citation: Mierzykowski S.E., L.J. Welch, C.S. Todd, B. Connery and C.R. DeSorbo. 2013. Contaminant assessment of coastal bald eagles at Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge and Acadia National Park. USFWS. Spec. Proj. Rep. FY12‐MEFO‐ 2‐EC. Maine Field Office. Orono, ME. 56 pp. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Maine Field Office Special Project Report: FY12‐MEFO‐2‐EC Contaminant Assessment of Coastal Bald Eagles at Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge and Acadia National Park DEQ ID: 200950001.1 Region 5 ID: FF05E1ME00‐1261‐5N46 (filename: 1261‐5N46_FinalReport.pdf) by Steven E. Mierzykowski and Linda J. Welch, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Charles S. Todd, Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Bruce Connery, National Park Service and Christopher R. DeSorbo, Biodiversity Research Institute September 2013 Congressional Districts #1 and #2 1 Executive Summary Environmental contaminants including organochlorine compounds (e.g., polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE)), polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE), and mercury were measured in 16 non‐viable or abandoned bald eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus eggs and 65 nestling blood samples collected between 2000 and 2012 from the Maine coast. -

The Quest for Lobster Stock Boundaries in the Canadian

NOT TO BE CITED WITHOUT PRIOR REFERENCE TO THE AUTHOR(S) Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization Serial No. N615 NAFO SCR Doc. 82/IX/107 FOURTH ANNUAL MEETING - SEPTEMBER 1982 The Quest for Lobster Stoclg Boundaries in the Canadian Maritimes by A. Camp ell and R. K. Mohnl Invertebrates and Marine Plants Division Fisheries Research Branch, Department of Fisheries and Oceans Biological Station, St. Andrews, N. B., Canada EOG 2X0 P. O. Box 550, H lifax, N. S., Canada B3J 2S7 Abstract Historical and recent datO on lobsters (Homarus americanus) from the Canadian maritimes were examin4d for stock differences with the object of defining lobster population bot ndaries. Using pattern recognition techniques, historical lobster landings (1892-1981) from 32 areas resulted in grouping the landing trends into 7-8 areas. Examination of morphometrics data, landing trends, population parameters (growth and size at aturity), movement of tagged lobsters, and general surface currents that might indicate larval drift, suggested the following general lobster stock areas: Western maritimes which included the Bay of Fundy, inshore and possibly offshore) southwestner Nova Scotia (to Shelburne Co.), The Eastern Coast of Nova Scotia (Queens to Cape Breton Counties) which seems to be a transition zone f,r lobsters between the Gulf of Maine and the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and 3. Southern Gulf of St. Lawrence STOCK DISCRI INATION SYMPOSIUM Key words: Homarus americanus; lobsters; stocks; population dynamics; morphonietrics; landing statistics; electrophoresis; recruitment; tagging; movement. General Introduction Historically, there have been various debates amongst biologists, fishery managers, and fishermen as to the geographic discreteness of lobster (Homarus americanus) populations on the Atlantic Coast of North America (eg. -

Guidelines for Long Combination Vehicles (Lcvs) in the Province of New Brunswick

Guidelines for Long Combination Vehicles (LCVs) in the Province of New Brunswick Department of Transportation First issue August 2008 Version 6.3 – December 2020 Ce document est disponible en français Table of Contents 1.0 Program overview ......................................................................................... 1 2.0 Submission of application ............................................................................. 1 3.0 Permissible LCV configurations, operating routes and turning template requirements ................................................................................................. 2 4.0 Permit general conditions.............................................................................. 5 5.0 Permit operating conditions ........................................................................... 6 6.0 Freight conditions ........................................................................................ 12 7.0 The APTA LCV Driver’s Certificate ............................................................. 12 8.0 Reportable Collision/incident reporting procedures ..................................... 13 Appendix 1: Information Required to Support LCV Application ........................... 14 Appendix 2: LCV A-train configuration ................................................................ 18 Appendix 3: LCV B-train configuration ................................................................ 20 Appendix 4: LCV Double Stinger-Steer Auto Carrier………………………………22 Appendix 5: Overview of the APTA -

Ecoregions of New England Forested Land Cover, Nutrient-Poor Frigid and Cryic Soils (Mostly Spodosols), and Numerous High-Gradient Streams and Glacial Lakes

58. Northeastern Highlands The Northeastern Highlands ecoregion covers most of the northern and mountainous parts of New England as well as the Adirondacks in New York. It is a relatively sparsely populated region compared to adjacent regions, and is characterized by hills and mountains, a mostly Ecoregions of New England forested land cover, nutrient-poor frigid and cryic soils (mostly Spodosols), and numerous high-gradient streams and glacial lakes. Forest vegetation is somewhat transitional between the boreal regions to the north in Canada and the broadleaf deciduous forests to the south. Typical forest types include northern hardwoods (maple-beech-birch), northern hardwoods/spruce, and northeastern spruce-fir forests. Recreation, tourism, and forestry are primary land uses. Farm-to-forest conversion began in the 19th century and continues today. In spite of this trend, Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and 5 level III ecoregions and 40 level IV ecoregions in the New England states and many Commission for Environmental Cooperation Working Group, 1997, Ecological regions of North America – toward a common perspective: Montreal, Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 71 p. alluvial valleys, glacial lake basins, and areas of limestone-derived soils are still farmed for dairy products, forage crops, apples, and potatoes. In addition to the timber industry, recreational homes and associated lodging and services sustain the forested regions economically, but quantity of environmental resources; they are designed to serve as a spatial framework for continue into ecologically similar parts of adjacent states or provinces. they also create development pressure that threatens to change the pastoral character of the region. -

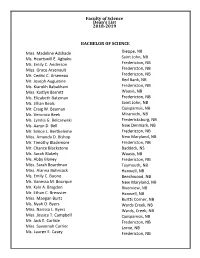

Faculty of Science Dean's List 2018-2019

Faculty of Science Dean's List 2018-2019 BACHELOR OF SCIENCE Miss. Madeline Adshade Dieppe, NB Ms. Heartswill E. Agbaku Saint John, NB Ms. Emily C. Anderson Fredericton, NB Miss. Grace Arsenault Fredericton, NB Mr. Cedric C. Arseneau Fredericton, NB Mr. Joseph Augustine Red Bank, NB Ms. Kiarokh Babakhani Fredericton, NB Miss. Kaitlyn Barrett Waasis, NB Ms. Elizabeth Bateman Fredericton, NB Ms. Jillian Beals Saint John, NB Mr. Craig W. Beaman Quispamsis, NB Ms. Veronica Beek Miramichi, NB Ms. Lyndia G. Belczewski Fredericksburg, NB Ms. Aaryn D. Bell New Denmark, NB Mr. Simon L. Bertheleme Fredericton, NB Miss. Amanda D. Bishop New Maryland, NB Mr. Timothy Blackmore Fredericton, NB Mr. Chance Blackstone Baddeck, NS Ms. Sarah Blakely Waasis, NB Ms. Abby Blaney Fredericton, NB Miss. Sarah Boardman Taymouth, NB Miss. Alanna Bohnsack Hanwell, NB Ms. Emily C. Boone Beechwood, NB Ms. Vanessa M. Bourque New Maryland, NB Mr. Kyle A. Bragdon Riverview, NB Mr. Ethan C. Brewster Hanwell, NB Miss. Maegan Burtt Burtts Corner, NB Ms. Nyah D. Byers Wards Creek, NB Miss. Narissa L. Byers Wards, Creek, NB Miss. Jessica T. Campbell Quispamsis, NB Mr. Jack E. Carlisle Fredericton, NB Miss. Savannah Carrier Lorne, NB Ms. Lauren E. Casey Fredericton, NB Mr. Kevin D. Comeau Mr. Nicholas F. Comeau Miss Emma M. Connell BACHELOR OF SCIENCE Ms. Jennifer Chan Fredericton, NB Mr. Benjamin Chase Fredericton, NB Mr. Matthew L. Clinton Fredericton, NB Miss. Grace M. Coles North Milton, PE Ms. Emma A. Collings Montague, PE Mr. Jordan W. Conrad Dartmouth, NS Mr. Samuel R. Cookson Quispamsis, NB Ms. Kelsey E. -

Flood Frequency Analyses for New Brunswick Rivers Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2920

Flood Frequency Analyses for New Brunswick Rivers Aucoin, F., D. Caissie, N. El-Jabi and N. Turkkan Department of Fisheries and Oceans Gulf Region Oceans and Science Branch Diadromous Fish Section P.O. Box 5030, Moncton, NB, E1C 9B6 2011 Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2920 Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Technical reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which is not normally appropriate for primary literature. Technical reports are directed primarily toward a worldwide audience and have an international distribution. No restriction is placed on subject matter and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of Fisheries and Oceans, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Technical reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in the data base Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts. Technical reports are produced regionally but are numbered nationally. Requests for individual reports will be filled by the issuing establishment listed on the front cover and title page. Numbers 1-456 in this series were issued as Technical Reports of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 457-714 were issued as Department of the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service, Research and Development Directorate Technical Reports. Numbers 715-924 were issued as Department of Fisheries and Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service Technical Reports. The current series name was changed with report number 925. Rapport technique canadien des sciences halieutiques et aquatiques Les rapports techniques contiennent des renseignements scientifiques et techniques qui constituent une contribution aux connaissances actuelles, mais qui ne sont pas normalement appropriés pour la publication dans un journal scientifique. -

Striped Bass Morone Saxatilis

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Striped Bass Morone saxatilis in Canada Southern Gulf of St. Lawrence Population St. Lawrence Estuary Population Bay of Fundy Population SOUTHERN GULF OF ST. LAWRENCE POPULATION - THREATENED ST. LAWRENCE ESTUARY POPULATION - EXTIRPATED BAY OF FUNDY POPULATION - THREATENED 2004 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2004. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Striped Bass Morone saxatilis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 43 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Jean Robitaille for writing the status report on the Striped Bass Morone saxatilis prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Claude Renaud the COSEWIC Freshwater Fish Species Specialist Subcommittee Co-chair. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Ếgalement disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la situation de bar rayé (Morone saxatilis) au Canada. Cover illustration: Striped Bass — Drawing from Scott and Crossman, 1973. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2004 Catalogue No. CW69-14/421-2005E-PDF ISBN 0-662-39840-8 HTML: CW69-14/421-2005E-HTML 0-662-39841-6 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – November 2004 Common name Striped Bass (Southern Gulf of St. -

Industrial Park

VILLAGE OF PERTH-ANDOVER, N.B. Village of WH ET ERE P LS ME Perth-Andover EOPLE AND T RAI Perth-Andover Industrial Park "Home of the Best Power Rates in New Brunswick” CONTACT Mr. Dan Dionne Chief Administrative Officer Village of Perth-Andover 1131 West Riverside Drive Perth-Andover, New Brunswick E7H 5G5 Telephone: (506) 273-4959 Facsimile: (506) 273-4947 Email: [email protected] Website: www.perth-andover.com HISTORY OVERVIEW In 1991 the municipality established a 25 acre block of land for an industrial Perth-Andover is located on the Saint John River, 40 kilometres south of park. Several businesses have established themselves in the Industrial Grand Falls near the mouth of the Tobique River. Perth is located on the Park, and the municipality is currently expanding the park to accommodate east side of the river and Andover is located on the west side. The two future demand. Businesses wishing to establish in the park can expect the villages were amalgamated in 1966 and have a population service area in Mayor and Council to do whatever possible to assist them. Perth-Andover excess of 6,000 people. Nestled between the rolling hills of the upper river is ideally located for businesses looking for excellent access to the United valley, this picturesque village is often referred to as the "Gateway to the States and to Ontario and Quebec. Combine this with an excellent quality of Tobique". The Municipality is ten kilometres west of the U.S. border and life and you have one of the most attractive areas in the province for approximately 80 kilometres north of Woodstock and the entrance to locating new industry. -

Kennebec Estuary Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance Kennebec Estuary

Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance: Kennebec Estuary Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance Kennebec Estuary WHY IS THIS AREA SIGNIFICANT? The Kennebec Estuary Focus Area contains more than 20 percent of Maine’s tidal marshes, a significant percentage of Maine’s sandy beach and associated dune Biophysical Region habitats, and globally rare pitch pine • Central Maine Embayment woodland communities. More than two • Cacso Bay Coast dozen rare plant species inhabit the area’s diverse natural communities. Numerous imperiled species of animals have been documented in the Focus Area, and it contains some of the state’s best habitat for bald eagles. OPPORTUNITIES FOR CONSERVATION » Work with willing landowners to permanently protect remaining undeveloped areas. » Encourage town planners to improve approaches to development that may impact Focus Area functions. » Educate recreational users about the ecological and economic benefits provided by the Focus Area. » Monitor invasive plants to detect problems early. » Find ways to mitigate past and future contamination of the watershed. For more conservation opportunities, visit the Beginning with Habitat Online Toolbox: www.beginningwithhabitat.org/ toolbox/about_toolbox.html. Rare Animals Rare Plants Natural Communities Bald Eagle Lilaeopsis Estuary Bur-marigold Coastal Dune-marsh Ecosystem Spotted Turtle Mudwort Long-leaved Bluet Maritime Spruce–Fir Forest Harlequin Duck Dwarf Bulrush Estuary Monkeyflower Pitch Pine Dune Woodland Tidewater Mucket Marsh Bulrush Smooth Sandwort