Emmerik72phase1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modelling and Numerical Simulation of Phase Separation in Polymer Modified Bitumen by Phase- Field Method

http://www.diva-portal.org Postprint This is the accepted version of a paper published in Materials & design. This paper has been peer- reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof-corrections or journal pagination. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Zhu, J., Lu, X., Balieu, R., Kringos, N. (2016) Modelling and numerical simulation of phase separation in polymer modified bitumen by phase- field method. Materials & design, 107: 322-332 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2016.06.041 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-188830 ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Modelling and numerical simulation of phase separation in polymer modified bitumen by phase-field method Jiqing Zhu a,*, Xiaohu Lu b, Romain Balieu a, Niki Kringos a a Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Brinellvägen 23, SE-100 44 Stockholm, Sweden b Nynas AB, SE-149 82 Nynäshamn, Sweden * Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] (J. Zhu) Abstract In this paper, a phase-field model with viscoelastic effects is developed for polymer modified bitumen (PMB) with the aim to describe and predict the PMB storage stability and phase separation behaviour. The viscoelastic effects due to dynamic asymmetry between bitumen and polymer are represented in the model by introducing a composition-dependent mobility coefficient. A double-well potential for PMB system is proposed on the basis of the Flory-Huggins free energy of mixing, with some simplifying assumptions made to take into account the complex chemical composition of bitumen. -

Phase Diagrams and Phase Separation

Phase Diagrams and Phase Separation Books MF Ashby and DA Jones, Engineering Materials Vol 2, Pergamon P Haasen, Physical Metallurgy, G Strobl, The Physics of Polymers, Springer Introduction Mixing two (or more) components together can lead to new properties: Metal alloys e.g. steel, bronze, brass…. Polymers e.g. rubber toughened systems. Can either get complete mixing on the atomic/molecular level, or phase separation. Phase Diagrams allow us to map out what happens under different conditions (specifically of concentration and temperature). Free Energy of Mixing Entropy of Mixing nA atoms of A nB atoms of B AM Donald 1 Phase Diagrams Total atoms N = nA + nB Then Smix = k ln W N! = k ln nA!nb! This can be rewritten in terms of concentrations of the two types of atoms: nA/N = cA nB/N = cB and using Stirling's approximation Smix = -Nk (cAln cA + cBln cB) / kN mix S AB0.5 This is a parabolic curve. There is always a positive entropy gain on mixing (note the logarithms are negative) – so that entropic considerations alone will lead to a homogeneous mixture. The infinite slope at cA=0 and 1 means that it is very hard to remove final few impurities from a mixture. AM Donald 2 Phase Diagrams This is the situation if no molecular interactions to lead to enthalpic contribution to the free energy (this corresponds to the athermal or ideal mixing case). Enthalpic Contribution Assume a coordination number Z. Within a mean field approximation there are 2 nAA bonds of A-A type = 1/2 NcAZcA = 1/2 NZcA nBB bonds of B-B type = 1/2 NcBZcB = 1/2 NZ(1- 2 cA) and nAB bonds of A-B type = NZcA(1-cA) where the factor 1/2 comes in to avoid double counting and cB = (1-cA). -

Phase Separation Phenomena in Solutions of Polysulfone in Mixtures of a Solvent and a Nonsolvent: Relationship with Membrane Formation*

Phase separation phenomena in solutions of polysulfone in mixtures of a solvent and a nonsolvent: relationship with membrane formation* J. G. Wijmans, J. Kant, M. H. V. Mulder and C. A. Smolders Department of Chemical Technology, Twente University of Technology, PO Box 277, 7500 AE Enschede, The Netherlands (Received 22 October 1984) The phase separation phenomena in ternary solutions of polysulfone (PSI) in mixtures of a solvent and a nonsolvent (N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc) and water, in most cases) are investigated. The liquid-liquid demixing gap is determined and it is shown that its location in the ternary phase diagram is mainly determined by the PSf-nonsolvent interaction parameter. The critical point in the PSf/DMAc/water system lies at a high polymer concentration of about 8~o by weight. Calorimetric measurements with very concentrated PSf/DMAc/water solutions (prepared through liquid-liquid demixing, polymer concentration of the polymer-rich phase up to 60%) showed no heat effects in the temperature range of -20°C to 50°C. It is suggested that gelation in PSf systems is completely amorphous. The results are incorporated into a discussion of the formation of polysulfone membranes. (Keywords: polysulfone; solutions; liquid-liquid demixing; crystallization; membrane structures; membrane formation) INTRODUCTION THEORY The field of membrane filtration covers a broad range of Membrane formation different separation techniques such as: hyperfiltration, In the phase inversion process a membrane is made by reverse osmosis, ultrafiltration, microfiltration, gas sepa- casting a polymer solution on a support and then bringing ration and pervaporation. Each process makes use of the solution to phase separation by means of solvent specific membranes which must be suited for the desired outflow and/or nonsolvent inflow. -

Partition Coefficients in Mixed Surfactant Systems

Partition coefficients in mixed surfactant systems Application of multicomponent surfactant solutions in separation processes Vom Promotionsausschuss der Technischen Universität Hamburg-Harburg zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor-Ingenieur genehmigte Dissertation von Tanja Mehling aus Lohr am Main 2013 Gutachter 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Irina Smirnova 2. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Gabriele Sadowski Prüfungsausschussvorsitzender Prof. Dr. Raimund Horn Tag der mündlichen Prüfung 20. Dezember 2013 ISBN 978-3-86247-433-2 URN urn:nbn:de:gbv:830-tubdok-12592 Danksagung Diese Arbeit entstand im Rahmen meiner Tätigkeit als wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin am Institut für Thermische Verfahrenstechnik an der TU Hamburg-Harburg. Diese Zeit wird mir immer in guter Erinnerung bleiben. Deshalb möchte ich ganz besonders Frau Professor Dr. Irina Smirnova für die unermüdliche Unterstützung danken. Vielen Dank für das entgegengebrachte Vertrauen, die stets offene Tür, die gute Atmosphäre und die angenehme Zusammenarbeit in Erlangen und in Hamburg. Frau Professor Dr. Gabriele Sadowski danke ich für das Interesse an der Arbeit und die Begutachtung der Dissertation, Herrn Professor Horn für die freundliche Übernahme des Prüfungsvorsitzes. Weiterhin geht mein Dank an das Nestlé Research Center, Lausanne, im Besonderen an Herrn Dr. Ulrich Bobe für die ausgezeichnete Zusammenarbeit und der Bereitstellung von LPC. Den Studenten, die im Rahmen ihrer Abschlussarbeit einen wertvollen Beitrag zu dieser Arbeit geleistet haben, möchte ich herzlichst danken. Für den außergewöhnlichen Einsatz und die angenehme Zusammenarbeit bedanke ich mich besonders bei Linda Kloß, Annette Zewuhn, Dierk Claus, Pierre Bräuer, Heike Mushardt, Zaineb Doggaz und Vanya Omaynikova. Für die freundliche Arbeitsatmosphäre, erfrischenden Kaffeepausen und hilfreichen Gespräche am Institut danke ich meinen Kollegen Carlos, Carsten, Christian, Mohammad, Krishan, Pavel, Raman, René und Sucre. -

Chapter 9: Other Topics in Phase Equilibria

Chapter 9: Other Topics in Phase Equilibria This chapter deals with relations that derive in cases of equilibrium between combinations of two co-existing phases other than vapour and liquid, i.e., liquid-liquid, solid-liquid, and solid- vapour. Each of these phase equilibria may be employed to overcome difficulties encountered in purification processes that exploit the difference in the volatilities of the components of a mixture, i.e., by vapour-liquid equilibria. As with the case of vapour-liquid equilibria, the objective is to derive relations that connect the compositions of the two co-existing phases as functions of temperature and pressure. 9.1 Liquid-liquid Equilibria (LLE) 9.1.1 LLE Phase Diagrams Unlike gases which are miscible in all proportions at low pressures, liquid solutions (binary or higher order) often display partial immiscibility at least over certain range of temperature, and composition. If one attempts to form a solution within that certain composition range the system splits spontaneously into two liquid phases each comprising a solution of different composition. Thus, in such situations the equilibrium state of the system is two phases of a fixed composition corresponding to a temperature. The compositions of two such phases, however, change with temperature. This typical phase behavior of such binary liquid-liquid systems is depicted in fig. 9.1a. The closed curve represents the region where the system exists Fig. 9.1 Phase diagrams for a binary liquid system showing partial immiscibility in two phases, while outside it the state is a homogenous single liquid phase. Take for example, the point P (or Q). -

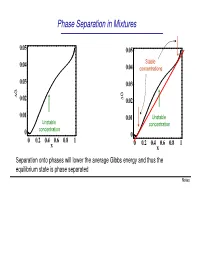

Phase Separation in Mixtures

Phase Separation in Mixtures 0.05 0.05 0.04 Stable 0.04 concentrations 0.03 0.03 G G ∆ 0.02 ∆ 0.02 0.01 0.01 Unstable Unstable concentration concentration 0 0 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 x x Separation onto phases will lower the average Gibbs energy and thus the equilibrium state is phase separated Notes Phase Separation versus Temperature Note that at higher temperatures the region of concentrations where phase separation takes place shrinks and G eventually disappears T increases ∆G = ∆U −T∆S This is because the term -T∆S becomes large at high temperatures. You can say that entropy “wins” over the potential energy cost at high temperatures Microscopically, the kinetic energy becomes x much larger than potential at high T, and the 1 x2 molecules randomly “run around” without noticing potential energy and thus intermix Oil and water mix at high temperature Notes Liquid-Gas Phase Separation in a Mixture A binary mixture can exist in liquid or gas phases. The liquid and gas phases have different Gibbs potentials as a function of mole fraction of one of the components of the mixture At high temperatures the Ggas <Gliquid because the entropy of gas is greater than that of liquid Tb2 T At lower temperatures, the two Gibbs b1 potentials intersect and separation onto gas and liquid takes place. Notes Boiling of a binary mixture Bubble point curve Dew point If we have a liquid at pint A that contains F A gas curve a molar fraction x1 of component 1 and T start heating it: E D - First the liquid heats to a temperature T’ C at constant x A and arrives to point B. -

Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation in Concentrated Solutions of Non-Crystallizable Polymers by Spinodal Decomposition by C

Kolloid-Z. u. Z. Polymere 243, 14-20 (1971 ) From the AKZO Research Laboratories Arnhem (The ~Vetherlands) Liquid-liquid phase separation in concentrated solutions of non-crystallizable polymers by spinodal decomposition By C. A. Smolders, J. J. van Aartsen, and A. Steenbergen With 11 figures (Received June 15, 1970) Introduction We will describe here under what condi- In the past, investigations of phase separa- tions spinodal decomposition can be expect- tion in concentrated polymer solutions cen- ed for polymer solutions. A number of ob- tered first of all on the crystallization kinet- servations on phase separation in concen- ics (1) and morphology (2) of polymer crys- trated solutions of poly(2,6-dimethyl-l,4- tals growing from solutions and, secondly, phenylene ether), (PPO| Tg = 210 ~ and on the equilibrium thermodynamic proper- of an ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer ties of liquid-liquid phase separation phe- (Elvax-40), Tg ~ 0 ~ will be reported, which nomena (3). will make it clear that spinodal decompo- Papkov and Yefimova (4) have recently sition can be realized in polymer solutions. given a classification of different types of phase separation for polymer solutions, essen- Thermodynamic considerations tially the two types mentioned above, in which they also pay some attention to the Fig. 1 a and b, gives a schematic represen- difference in final state of separation (i. e. tation of the thermodynamics of liquid- "gel" or two liquid layers) and to the mechanism of separation itself. For liquid- A Fm [~_ liquid phase separation of solutions of non- crystallizable polymers the difference in I LE -r final state is ascribed to a combined effect of the thermodynamics of the system (the width of the miscibility gap in the temperature-com- position diagram) and the flow properties of the concentrated polymer phase. -

Pak 2016, Sequence Determinants of Intracellular Phase Separation By

Article Sequence Determinants of Intracellular Phase Separation by Complex Coacervation of a Disordered Protein Graphical Abstract Authors Chi W. Pak, Martyna Kosno, Alex S. Holehouse, ..., David R. Liu, Rohit V. Pappu, Michael K. Rosen Correspondence [email protected] (R.V.P.), [email protected] (M.K.R.) In Brief Pak et al. describe cellular liquid-liquid phase separation of a negatively charged intrinsically disordered protein, the Nephrin intracellular domain. Phase separation is driven by co-assembly with positively charged partners, a process termed complex coacervation. Disordered regions with NICD-like sequence features are common in the human proteome, suggesting complex coacervation may be widespread. Highlights d Disordered Nephrin intracellular domain (NICD) forms phase- separated nuclear bodies d NICD phase separates via complex coacervation d Aromatic/hydrophobic residues and high (À) charge density promote phase separation d Disordered regions with NICD-like sequence features are common in human proteome Pak et al., 2016, Molecular Cell 63, 72–85 July 7, 2016 ª 2016 Elsevier Inc. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.042 Molecular Cell Article Sequence Determinants of Intracellular Phase Separation by Complex Coacervation of a Disordered Protein Chi W. Pak,1 Martyna Kosno,1 Alex S. Holehouse,2,3 Shae B. Padrick,1 Anuradha Mittal,3 Rustam Ali,1 Ali A. Yunus,1 David R. Liu,4 Rohit V. Pappu,3,* and Michael K. Rosen1,* 1Department of Biophysics and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA 2Computational and Molecular Biophysics Graduate Program, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO 63130, USA 3Department of Biomedical Engineering and Center for Biological Systems Engineering, Washington University in St. -

Lecture 9: Polymer Solutions – Phase Behavior

Prof. Tibbitt Lecture 9 Networks & Gels Lecture 9: Polymer solutions { Phase behavior Prof. Mark W. Tibbitt { ETH Z¨urich { 17 March 2020 1 Suggested reading • Molecular Driving Forces { Dill and Bromberg: Chapter 32 • Polymer Physics { Rubinstein and Colby: Chapters 4,5 • Soft Condensed Matter { Jones: Chapters 3,9 2 Flory-Huggins Theory In the last lecture, we derived the Flory-Huggins Theory for the Free Energy of mixing of polymer solutions. The derivation was general for species 1 and 2 with degree of polymerization x1 and x2 and is a more general expression of regular solution theory. In this discussion, we will look at what the Flory-Huggins theory tells us about phase behavior of polymers and how this differs from the behavior of small molecules. As we are no longer considering a lattice with N sites, we will revert back to using the term N as the degree of polymerization of our two species. Again we will consider two generic species A and B with degrees of polymerization NA and NB. Recall the form of the Free Energy of mixing per site from Flory-Huggins Theory: M ∆F M φA φB = ∆F¯ = ln φA + ln φB + χφAφB : (1) NkBT NA NB We will now use the term ∆F¯M as the Free Energy of mixing per site. 3 Phase behavior of polymer solutions In order to work with polymer solutions for industrial and biomedical applications, it is essential to understand the phase behavior of the systems. For example, we need to know under which conditions a polymer will dissolve in a solvent or if two polymers will be miscible. -

Critical Phenomena of Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation in Biomolecular Condensates

Critical Phenomena of Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation in Biomolecular Condensates Junlang Liu Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 02138 [email protected] (Dated: May 21, 2021) Biomolecular condensates, an important class of intracellular organelles, is considered to be formed by Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS) in vivo. Here, in this report, we focus on the critical region of LLPS, where we believe is the state that most cells live for spatiotemporally-resolved physiological activities. First, a brief introduction of LLPS and recent progress is presented. We then discuss critical phenomena of passive LLPS and active LLPS respectively from mean-field perspective with the help of some reported results. Current descriptions of passive LLPS are mainly based on Flory-Huggins model, which is still within the framework of mean-field Landau-Ginzburg model. For active LLPS, the application of external fields do affect the critical behaviour. This not only implies the importance of taking external energy/biochemical reactions into account for more precise description of in vivo LLPS, but also could be the origins of such rich intracellular activities. I. INTRODUCTION (such as ATP or post-translational modifications) influ- ence LLPS (i.e., out-of-equilibrium active process)? [4] Intracellular compartmentalization enables dynamical 3) How does heterogeneous cellular environments inter- and accurate information processes during the growth act with condensates? [5] and development of lives. Compared with well-studied membrane-bound organelles, researches on membrane- Although huge amounts of researches have been done, less organelles are still in its infancy. It has been well very few of them took a serious investigation on criticality established during the past decade that membrane-less or universality of LLPS/liquid-gel-solid transition. -

Relevance of Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation of Supersaturated Solution in Oral Absorption of Albendazole from Amorphous Solid Dispersions

pharmaceutics Article Relevance of Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation of Supersaturated Solution in Oral Absorption of Albendazole from Amorphous Solid Dispersions Kyosuke Suzuki 1,*, Kohsaku Kawakami 2,* , Masafumi Fukiage 3, Michinori Oikawa 4, Yohei Nishida 5, Maki Matsuda 6 and Takuya Fujita 7 1 Pharmaceutical and ADMET Research Department, Daiichi Sankyo RD Novare Co., Ltd., 1-16-13, Kitakasai, Edogawa-ku, Tokyo 134-8630, Japan 2 Research Center for Functionals Materials, National Institute for Materials Science, 1-1 Namiki, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-0044, Japan 3 Pharmaceutical R&D, Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., 3-3-1, Sakurai, Shimamoto-cho, Mishima-gun, Osaka 618-8585, Japan; [email protected] 4 Pharmaceutical Development Department, Sawai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., 5-2-30, Miyahara, Yodogawa-ku, Osaka 532-0003, Japan; [email protected] 5 Technology Research & Development, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd., 33-94, Enoki-cho, Suita, Osaka 564-0053, Japan; [email protected] 6 Research & Development Division, Towa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., 134, Chudoji Minami-machi, Shimogyo-ku, Kyoto 600-8813, Japan; [email protected] 7 College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Ritsumeikan University, 1-1-1 Noji-Higashi, Kusatsu, Shiga 525-8577, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (K.S.); [email protected] (K.K.); Tel.: +81-80-4383-5853 (K.S.); +81-29-860-4424 (K.K.) Citation: Suzuki, K.; Kawakami, K.; Fukiage, M.; Oikawa, M.; Nishida, Y.; Abstract: Amorphous solid dispersion (ASD) is one of the most promising formulation technologies Matsuda, M.; Fujita, T. Relevance of for improving the oral absorption of poorly soluble drugs, where the maintenance of supersaturation Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation of plays a key role in enhancing the absorption process. -

Thermovid 10 10

Statistical Molecular Thermodynamics Christopher J. Cramer Video 10.10 Review of Module 10 Critical Concepts from Module 10 • The free energy of a multicomponent system is the sum of the chemical potentials of the different components. • Partial molar quantities are defined as " ∂Z % Z j = $ ' #∂n j & ni≠ j ,P,T where for a pure substance, the value is that for one mole of that substance, while the value in a mixture will be dependent on the composition. • All extensive thermodynamic quantities have partial molar equivalents. Critical Concepts from Module 10 • The Gibbs-Duhem equation establishes a relationship between the chemical potentials of two substances in a mixture as a function of composition: Gibbs-Duhem Equation x1dµ1 + x2dµ2 = 0 (constant T and P) • At equilibrium, a given component has the same chemical potential€ in all phases in which it is present. • For systems having liquid and vapor phases in equilibrium, the chemical potential (1 bar standard state) can be expressed as vap vap,! sol µ j = µ j (T)+ RT ln Pj = µ j Critical Concepts from Module 10 • An alternative expression for the chemical potential in the mole fraction standard state is sol * Pj µ j = µ j (l) + RT ln * Pj • For an ideal solution, Raoult’s law holds, which states that for all components Pj = xjPj* where xj is the mole fraction of component j. • The chemical€ potential in an ideal solution is then sol * µ j = µ j (l) + RT ln x j • Mixing to form an ideal solution is always favorable and is driven entirely by entropy € Critical Concepts from Module 10 • Differing compositions in liquid and vapor phases in equilibrium at a given temperature permit fractional distillation of ideal solutions.