Some Observations on the Composition of the "Core Chapters" of the Mozi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mohist Theoretic System: the Rivalry Theory of Confucianism and Interconnections with the Universal Values and Global Sustainability

Cultural and Religious Studies, March 2020, Vol. 8, No. 3, 178-186 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2020.03.006 D DAVID PUBLISHING Mohist Theoretic System: The Rivalry Theory of Confucianism and Interconnections With the Universal Values and Global Sustainability SONG Jinzhou East China Normal University, Shanghai, China Mohism was established in the Warring State period for two centuries and half. It is the third biggest schools following Confucianism and Daoism. Mozi (468 B.C.-376 B.C.) was the first major intellectual rivalry to Confucianism and he was taken as the second biggest philosophy in his times. However, Mohism is seldom studied during more than 2,000 years from Han dynasty to the middle Qing dynasty due to his opposition claims to the dominant Confucian ideology. In this article, the author tries to illustrate the three potential functions of Mohism: First, the critical/revision function of dominant Confucianism ethics which has DNA functions of Chinese culture even in current China; second, the interconnections with the universal values of the world; third, the biological constructive function for global sustainability. Mohist had the fame of one of two well-known philosophers of his times, Confucian and Mohist. His ideas had a decisive influence upon the early Chinese thinkers while his visions of meritocracy and the public good helps shape the political philosophies and policy decisions till Qin and Han (202 B.C.-220 C.E.) dynasties. Sun Yet-sen (1902) adopted Mohist concepts “to take the world as one community” (tian xia wei gong) as the rationale of his democratic theory and he highly appraised Mohist concepts of equity and “impartial love” (jian ai). -

Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy

Readings In Classical Chinese Philosophy edited by Philip J. Ivanhoe University of Michigan and Bryan W. Van Norden Vassar College Seven Bridges Press 135 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10010-7101 Copyright © 2001 by Seven Bridges Press, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. Publisher: Ted Bolen Managing Editor: Katharine Miller Composition: Rachel Hegarty Cover design: Stefan Killen Design Printing and Binding: Victor Graphics, Inc. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Readings in classical Chinese philosophy / edited by Philip J. Ivanhoe, Bryan W. Van Norden. p. cm. ISBN 1-889119-09-1 1. Philosophy, Chinese--To 221 B.C. I. Ivanhoe, P. J. II. Van Norden, Bryan W. (Bryan William) B126 .R43 2000 181'.11--dc21 00-010826 Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CHAPTER TWO Mozi Introduction Mozi \!, “Master Mo,” (c. 480–390 B.C.E.) founded what came to be known as the Mojia “Mohist School” of philosophy and is the figure around whom the text known as the Mozi was formed. His proper name is Mo Di \]. Mozi is arguably the first true philosopher of China known to us. He developed systematic analyses and criticisms of his opponents’ posi- tions and presented an array of arguments in support of his own philo- sophical views. His interest and faith in argumentation led him and his later followers to study the forms and methods of philosophical debate, and their work contributed significantly to the development of early Chinese philosophy. -

Mozi 31: Explaining Ghosts, Again Roel Sterckx* One Prominent Feature

MOZI 31: EXPLAINING GHOSTS, AGAIN Roel Sterckx* One prominent feature associated with Mozi (Mo Di 墨翟; ca. 479–381 BCE) and Mohism in scholarship of early Chinese thought is his so-called unwavering belief in ghosts and spirits. Mozi is often presented as a Chi- nese theist who stands out in a landscape otherwise dominated by this- worldly Ru 儒 (“classicists” or “Confucians”).1 Mohists are said to operate in a world clad in theological simplicity, one that perpetuates folk reli- gious practices that were alive among the lower classes of Warring States society: they believe in a purely utilitarian spirit world, they advocate the use of simple do-ut-des sacrifices, and they condemn the use of excessive funerary rituals and music associated with Ru elites. As a consequence, it is alleged, unlike the Ru, Mohist religion is purely based on the idea that one should seek to appease the spirit world or invoke its blessings, and not on the moral cultivation of individuals or communities. This sentiment is reflected, for instance, in the following statement by David Nivison: Confucius treasures the rites for their value in cultivating virtue (while virtually ignoring their religious origin). Mozi sees ritual, and the music associated with it, as wasteful, is exasperated with Confucians for valuing them, and seems to have no conception of moral self-cultivation whatever. Further, Mozi’s ethics is a “command ethic,” and he thinks that religion, in the bald sense of making offerings to spirits and doing the things they want, is of first importance: it is the “will” of Heaven and the spirits that we adopt the system he preaches, and they will reward us if we do adopt it. -

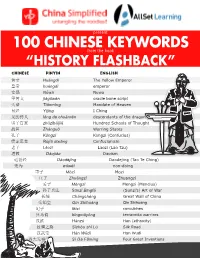

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

View Sample Pages

This Book Is Dedicated to the Memory of John Knoblock 未敗墨子道 雖然歌而非歌哭而非哭樂而非樂 是果類乎 I would not fault the Way of Master Mo. And yet if you sang he condemned singing, if you cried he condemned crying, and if you made music he condemned music. What sort was he after all? —Zhuangzi, “In the World” A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. Although the institute is responsible for the selection and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibility for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. The China Research Monograph series is one of the several publication series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. Send correspondence and manuscripts to Katherine Lawn Chouta, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies 2223 Fulton Street, 6th Floor Berkeley, CA 94720-2318 [email protected] Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mo, Di, fl. 400 B.C. [Mozi. English. Selections] Mozi : a study and translation of the ethical and political writings / by John Knoblock and Jeffrey Riegel. pages cm. -- (China research monograph ; 68) English and Chinese. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55729-103-9 (alk. paper) 1. Mo, Di, fl. 400 B.C. Mozi. I. Knoblock, John, translator, writer of added commentary. II. Riegel, Jeffrey K., 1945- translator, writer of added commentary. III. Title. B128.M79E5 2013 181'.115--dc23 2013001574 Copyright © 2013 by the Regents of the University of California. -

The Tianxia System and the Search for a Common Ground in the Comparative Ethics of War

The Tianxia System and the Search for a Common Ground in the Comparative Ethics of War Edmund Frettingham and Yih-Jye Hwang This paper explores the conclusions of recent research on the ethics of war in Chinese traditional political thought, asking how they have been shaped by understandings of the nature, meaning and significance of global ethical di- versity. After outlining the major contours of Chinese traditional ethics of war, we propose that the significance of this material has been understood within the terms of both liberal and communitarian meta-ethical assumptions. These assumptions have shaped how the relationship between Chinese and West- ern traditions has been understood, limiting this research in unhelpful ways. While liberal assumptions lead to authors discounting the distinctiveness of Chinese traditions, communitarian approaches seek to find common ground between traditions to mitigate the danger of intercultural conflict. The common ground solution is ultimately undermined by the communitarian assumptions that made it seem urgent. In response to these problems, we propose that a more radically communitarian mode of engagement should guide the compar- ative dimension of research into non-Western ethics of war. Key Words: Comparative ethics of war, Just war, Tianxia, Chinese political thought, Post-Western IR Korean conservatism, Japanese statism, European fascism, progressivism, Parg- *Edmund Frettingham ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor of International Relations at Leiden University. His research interests include religion and secularism in world politics, ethics, and critical security studies. ** Yih-Jye Hwang ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor of International Relations at Leiden University. -

Disciplining of a Society Social Disciplining and Civilizing Processes in Contemporary China

Disciplining of a Society Social Disciplining and Civilizing Processes in Contemporary China Thomas Heberer August 2020 Disciplining of a Society Social Disciplining and Civilizing Processes in Contemporary China Thomas Heberer August 2020 disciplining of a society Social Disciplining and Civilizing Processes in Contemporary China about the author Thomas Heberer is Senior Professor of Chinese Politics and Society at the Insti- tute of Political Science and the Institute of East Asian Studies at the University Duisburg-Essen in Germany. He is specializing on issues such as political, social and institutional change, entrepreneurship, strategic groups, the Chinese developmen- tal state, urban and rural development, political representation, corruption, ethnic minorities and nationalities’ policies, the role of intellectual ideas in politics, field- work methodology, and political culture. Heberer is conducting fieldwork in China on almost an annual basis since 1981. He recently published the book “Weapons of the Rich. Strategic Action of Private Entrepreneurs in Contemporary China” (Singapore, London, New York: World Scientific 2020, co-authored by G. Schubert). On details of his academic oeuvre, research projects and publications see his website: ht tp:// uni-due.de/oapol/. iii disciplining of a society Social Disciplining and Civilizing Processes in Contemporary China about the ash center The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, edu- cation, and public discussion. By training the very best leaders, developing power- ful new ideas, and disseminating innovative solutions and institutional reforms, the Center’s goal is to meet the profound challenges facing the world’s citizens. -

China's First Liberal

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 China’s First Liberal F EVAN OSBORNE cholars and partisans of liberty often dispute whether liberty is the natural desire of all humans or—as Orlando Patterson (1992), among many others, S contends—the product of a distinctive Western history that runs through the Magna Carta, the Enlightenment, and the Federalist Papers. The most explicit con- sideration of why liberty is the just state of society is probably mostly Western, although, owing (ironically) to Western imperialism and in recent years to globaliza- tion, the appeal of limited government arguably has spread around the world. -

Why Is Chinese So Damn Hard?

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 27 August 31, 1991 $35.00 Schriftfestschrift: Essays on Writing and Language in Honor of John DeFrancis on His Eightieth Birthday edited by Victor H. Mair Order from: Department of Oriental Studies University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA Schriftfestschrift: Essays in Honor of John DeFrancis Why Chinese Is So Damn Hard by David Moser Dept. of Asian Languages and Cultures University of Michigan The first question any thoughtful person might ask when reading the title of this essay is, "Hard for whom?" A reasonable question. After all, Chinese people seem to learn it just fine. When little Chinese kids go through the "terrible twos", it's Chinese they use to drive their parents crazy, and in a few years the same kids are actually using those impossibly complicated Chinese characters to scribble love notes and shopping lists. So what do I mean by "hard"? Since I know at the outset that the whole tone of this document is going to involve a lot of whining and complaining, I may as well come right out and say exactly what I mean. I mean hard for me, a native English speaker trying to learn Chinese as an adult, going through the whole process with the textbooks, the tapes, the conversation partners, etc., — the whole torturous rigamarole. I mean hard for me — and, of course, for the many other Westerners who have spent years of their lives bashing their heads against the Great Wall of Chinese. If this were as far as I went, my statement would be a pretty empty one. -

Title the Mozi and Just War Theory in Pre-Han Thought Author(S)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HKU Scholars Hub Title The Mozi and Just War Theory in Pre-Han Thought Author(s) Fraser, CJ The 2014 Workshop on International Perspectives in the Citation Research of the Mohist Thought, Taipei, Taiwan, 18 October 2014. Issued Date 2014 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/206899 Rights Creative Commons: Attribution 3.0 Hong Kong License 1 The Mozi and Just War Theory in Pre-Han Thought Chris Fraser University of Hong Kong 1. Introduction China’s Warring States era (481–221 BCE) was marked by cruel, destructive, recurring warfare between the seven major warring states and numerous minor states. This incessant violence gave rise to an impassioned anti-aggression discourse led by the early Warring States philosopher and social activist Mozi and his followers, the most well-known critics of armed aggression. Initially, the Mohists may have simply opposed all military aggression. Later, however, they developed the more nuanced view that, although unprovoked aggression is wrong, defensive warfare—including defensive assistance to cities or states other than one’s own—and punitive aggression are sometimes justified. The writings collected in the Mozi 墨子 implicitly present an elaborate set of criteria by which to evaluate the justification for war. This article will examine these criteria and explore the extent to which they overlap with justifying conditions widely accepted in contemporary just war theory. One key finding will be that the Mohist criteria are so stringent that offensive war can be justified only very rarely and even defensive war is not always warranted. -

Mozi: the Man, the Consequentialist, and the Utilitarian

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2013 Mozi: the Man, the Consequentialist, and the Utilitarian Grace H. Mendenhall College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Mendenhall, Grace H., "Mozi: the Man, the Consequentialist, and the Utilitarian" (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 772. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/772 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mozi: the Man, the Consequentialist, and the Utilitarian A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy from The College of William and Mary by Grace Helen Mendenhall Accepted for ______________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ______________________________ Christopher Freiman, Director ______________________________ Maria Costa ______________________________ Timothy Costelloe ______________________________ Kevin Vose Introduction While little scholarship has been done on Master Mozi and his theory of ethics, those who study his work have contributed much to the discipline of philosophy as a whole. Originally, as he never achieved the fame of Confucius, Mencius, or Lao Tzu, Mozi’s work was often ignored. Unlike his fellows, until recently, Mozi’s writings were not translated and lacked explanatory companion texts. Unfortunately, much of his original works were also destroyed, leaving little for even those interested scholars to interpret.1 What philosophical scholarship has been done on Mozi’s ethics, in particular, is fairly controversial. -

Hiea 120: Thought and Society in Ancient China

HIEA 120: THOUGHT AND SOCIETY IN ANCIENT CHINA TuTh 11:00 – 12:20 CSB 002 Prof. Suzanne Cahill Office: HSS 3040 Phone: (858) 534-8105 Office hours: Thursday, 1:00 – 3:00 email: suzannecahill@gmail or by appointment Reader: Introduction This course introduces Chinese history, society, and thought from the earliest times through the Han dynasty. We focus on the development of early Chinese cultural systems, including philosophy, political institutions, the family, and material culture. We stress social and historical context, continuity and change, conflict and resolution, form and meaning. This is a pivotal period in Chinese history: the time of the Five Classics, followed by that of Confucius and other great thinkers, and later by the unification of China and the formation of geographical divisions we still recognize today, the governmental institutions of the imperial bureaucracy, and the patrilineal family system. As early Chinese history has had a deep impact on modern Chinese life and identity, we use contemporary examples to show the persistence and transformation of old ideas. Class combines lecture and discussion. The Powerpoint slides accompanying the lectures provide basic outlines of the lectures, including dates, hard-to-spell words, and suggestions for further reading. They are no substitute for coming to class and taking your own notes, but they should help you in organizing your notes and studying for exams. They will be posted on the WebCt. Every class, except for the first and last classes and the day of the midterm, includes participatory analysis of primary texts. The course framework is both chronological and thematic.