The Ptolemy-Copernicus Transition: Intertheoretic Context 98

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ptolemaic System Claudius Ptolemy

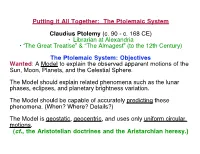

Putting it All Together: The Ptolemaic System Claudius Ptolemy (c. 90 - c. 168 CE) • Librarian at Alexandria • “The Great Treatise” & “The Almagest” (to the 12th Century) The Ptolemaic System: Objectives Wanted: A Model to explain the observed apparent motions of the Sun, Moon, Planets, and the Celestial Sphere. The Model should explain related phenomena such as the lunar phases, eclipses, and planetary brightness variation. The Model should be capable of accurately predicting these phenomena. (When? Where? Details?) The Model is geostatic, geocentric, and uses only uniform circular motions. (cf., the Aristotelian doctrines and the Aristarchian heresy.) The Ptolemaic System Observations • The apparent rotation of the Celestial Sphere • The annual motion of the Sun along the ecliptic • The monthly motion of the Moon The lunar phases and the synodic month Lunar and Solar Eclipses • The motions of the planets on the celestial sphere Direct and retrograde motions Planetary brightness variations Periodicities: The synodic periods Assumptions • A Geostatic cosmology (The Earth does not move.) • Uniform Circular motions (It is a “perfect” universe.) Approaches • The offsets and epicycles introduced by Hipparchus The Ptolemaic System For Inferior Planets (Mercury Venus) Deferent Period is 1 Year; Epicyclic period is the Synodic Period For Superior Planets (Mars, Jupiter, Saturn) Deferent Period is the Synodic period; Epicyclic Period is 1 year The Ptolemaic System (“To Scale”) Note: Indicated motions are with respect to the Celestial Sphere AGAIN: Problems with the Ptolemaic System Recollect the assumptions • The Earth doesn’t move (“geostatic”) • The Earth is at the center of the universe (“geocentric”) • All motions are circular (... or combinations thereof) • All motions are uniform (.. -

Strategies of Defending Astrology: a Continuing Tradition

Strategies of Defending Astrology: A Continuing Tradition by Teri Gee A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto © Copyright by Teri Gee (2012) Strategies of Defending Astrology: A Continuing Tradition Teri Gee Doctorate of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto 2012 Abstract Astrology is a science which has had an uncertain status throughout its history, from its beginnings in Greco-Roman Antiquity to the medieval Islamic world and Christian Europe which led to frequent debates about its validity and what kind of a place it should have, if any, in various cultures. Written in the second century A.D., Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos is not the earliest surviving text on astrology. However, the complex defense given in the Tetrabiblos will be treated as an important starting point because it changed the way astrology would be justified in Christian and Muslim works and the influence Ptolemy’s presentation had on later works represents a continuation of the method introduced in the Tetrabiblos. Abû Ma‘shar’s Kitâb al- Madkhal al-kabîr ilâ ‘ilm ahk. âm al-nujûm, written in the ninth century, was the most thorough surviving defense from the Islamic world. Roger Bacon’s Opus maius, although not focused solely on advocating astrology, nevertheless, does contain a significant defense which has definite links to the works of both Abû Ma‘shar and Ptolemy. As such, he demonstrates another stage in the development of astrology. -

PHIL 339 Intro Phil of Science, UO Philosophy Dept, Winter 2018

1 PHIL 339 Intro Phil of Science, UO Philosophy Dept, Winter 2018 Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Benjamin Franklin,Watson & Crick, Rosalind Franklin, Galileo Galilei, Dr. Linus Pauling, William Crawford Eddy, James Watt Maria Goeppert-Mayer, Charles Darwin, James Clerk Maxwell, Archimedes, Lise Meitner, Sigmund Freud, Irène Joliot-Curie Gregor Johann Mendel,Chien-Shiung Wu,Barbara McClintock, Neil DeGrasse Tyson. All Contents ©2017 Photo Researchers, Inc., 307 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY , 10016 212-758-3420 800-833- 9033 Science Source® is a registered trademark of Photo Researchers, Inc. / 2 PHIL 339 Intro Phil of Science, UO Philosophy Dept, Winter 2018 Course Data PHIL 339 Intro Phil of Science >2 4.00 cr. Grading Options: Optional for all students Instructor: Prof. N. Zack, Office: 239 SCH Phone: (541) 346-1547 Office Hours: WTh -2-3 See CRN for CommentsPrereqs/Comments: Prereq: one philosophy course (waiver available) *Note: This is a 2-hr course twice a week and discussion is built in. There will breaks and variations in subject matter to keep it interesting. OVERVIEW/DESCRIPTION (See also APPENDICES A-D AFTER SYLLABUS) Philosophy of Science is unique to philosophy. It raises questions about facts, theories, reality, explanation, and truth not often addressed by scientists or other humanistic scholars. This course will provide the basics of Philosophy of Science with concrete examples as science now applies to contemporary subjects such as Climate Change, Feminism, and Race. Students will have an opportunity to choose their own branches of inquiry for end-of-term reports. Work will consist of reading, discussion, and 4 3-page papers. -

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere A Constellation of Rare Books from the History of Science Collection The exhibition was made possible by generous support from Mr. & Mrs. James B. Hebenstreit and Mrs. Lathrop M. Gates. CATALOG OF THE EXHIBITION Linda Hall Library Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology Cynthia J. Rogers, Curator 5109 Cherry Street Kansas City MO 64110 1 Thinking Outside the Sphere is held in copyright by the Linda Hall Library, 2010, and any reproduction of text or images requires permission. The Linda Hall Library is an independently funded library devoted to science, engineering and technology which is used extensively by The exhibition opened at the Linda Hall Library April 22 and closed companies, academic institutions and individuals throughout the world. September 18, 2010. The Library was established by the wills of Herbert and Linda Hall and opened in 1946. It is located on a 14 acre arboretum in Kansas City, Missouri, the site of the former home of Herbert and Linda Hall. Sources of images on preliminary pages: Page 1, cover left: Peter Apian. Cosmographia, 1550. We invite you to visit the Library or our website at www.lindahlll.org. Page 1, right: Camille Flammarion. L'atmosphère météorologie populaire, 1888. Page 3, Table of contents: Leonhard Euler. Theoria motuum planetarum et cometarum, 1744. 2 Table of Contents Introduction Section1 The Ancient Universe Section2 The Enduring Earth-Centered System Section3 The Sun Takes -

Claudius Ptolemy: Tetrabiblos

CLAUDIUS PTOLEMY: TETRABIBLOS OR THE QUADRIPARTITE MATHEMATICAL TREATISE FOUR BOOKS OF THE INFLUENCE OF THE STARS TRANSLATED FROM THE GREEK PARAPHRASE OF PROCLUS BY J. M. ASHMAND London, Davis and Dickson [1822] This version courtesy of http://www.classicalastrologer.com/ Revised 04-09-2008 Foreword It is fair to say that Claudius Ptolemy made the greatest single contribution to the preservation and transmission of astrological and astronomical knowledge of the Classical and Ancient world. No study of Traditional Astrology can ignore the importance and influence of this encyclopaedic work. It speaks not only of the stars, but of a distinct cosmology that prevailed until the 18th century. It is easy to jeer at someone who thinks the earth is the cosmic centre and refers to it as existing in a sublunary sphere. However, our current knowledge tells us that the universe is infinite. It seems to me that in an infinite universe, any given point must be the centre. Sometimes scientists are not so scientific. The fact is, it still applies to us for our purposes and even the most rational among us do not refer to sunrise as earth set. It practical terms, the Moon does have the most immediate effect on the Earth which is, after all, our point of reference. She turns the tides, influences vegetative growth and the menstrual cycle. What has become known as the Ptolemaic Universe, consisted of concentric circles emanating from Earth to the eighth sphere of the Fixed Stars, also known as the Empyrean. This cosmology is as spiritual as it is physical. -

As Above, So Below. Astrology and the Inquisition in Seventeenth-Century New Spain

Department of History and Civilization As Above, So Below. Astrology and the Inquisition in Seventeenth-Century New Spain Ana Avalos Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, February 2007 EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE Department of History and Civilization As Above, So Below. Astrology and the Inquisition in Seventeenth-Century New Spain Ana Avalos Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board: Prof. Peter Becker, Johannes-Kepler-Universität Linz Institut für Neuere Geschichte und Zeitgeschichte (Supervisor) Prof. Víctor Navarro Brotons, Istituto de Historia de la Ciencia y Documentación “López Piñero” (External Supervisor) Prof. Antonella Romano, European University Institute Prof. Perla Chinchilla Pawling, Universidad Iberoamericana © 2007, Ana Avalos No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author A Bernardo y Lupita. ‘That which is above is like that which is below and that which is below is like that which is above, to achieve the wonders of the one thing…’ Hermes Trismegistus Contents Acknowledgements 4 Abbreviations 5 Introduction 6 1. The place of astrology in the history of the Scientific Revolution 7 2. The place of astrology in the history of the Inquisition 13 3. Astrology and the Inquisition in seventeenth-century New Spain 17 Chapter 1. Early Modern Astrology: a Question of Discipline? 24 1.1. The astrological tradition 27 1.2. Astrological practice 32 1.3. Astrology and medicine in the New World 41 1.4. -

The Humanities in Deconstruction: Raising the Question of the Post-Colonial University

ACCESS: CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN EDUCATION 2007, VOL. 26, NO. 1, 1–10 The humanities in deconstruction: Raising the question of the post-colonial university Michael A. Peters University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign ABSTRACT Derrida is, perhaps, the foremost philosopher of the humanities and of its place in the university. Over the long period of his career he has been concerned with the fate, status, place and contribution of the humanities. Through his deconstructive readings and writings he has done much not only to reinvent the Western tradition by attending closely to those texts which constitute it but also he has redefined its procedures and protocols, questioning and commenting upon the relationship between commentary and interpretation, the practice of quotation, the delimitation of a work and its singularity, its signature, and its context – the whole form of life of literary culture, together with textual practices and conventions that shape it. From his very early work he has occupied a marginal in-between space – simultaneously, textual, literary, philosophical, and political – a space that permitted him a freedom to question, to speculate and to draw new limits to humanitas. Derrida has demonstrated his power to reconceptualise and to reimagine the humanities in the space of the contemporary university. This paper discusses Derrida’s tasks for the new humanities (Trifonas & Peters, 2005). 1. Fundamentalisms and the need for a deconstructive humanities An appreciation of Derrida’s work can shed light on the growth and clash -

OR GREAT BOOK. Figure 10 Explains the Cosmographic System of The

36 THE "ALMAGEST" OR GREAT BOOK. Figure 10 explains the cosmographic system of the same astronomer. In the centre we see the Earth, externally surrounded by fire [which is precisely opposite to the truth, according to the fundamental principles of modern geology; but the reader will understand that we are not attempting here to expose the errors of Ptolemaus; we confine ourselves to a description of his system]. Above the Earth spreads the first crystalline heaven, which carries and conveys the Moon. In the second and third crystal heavens the planets Mercury and Venus respectively describe their epicycles. The fourth heaven belongs to the Sun ; wherein it traverses the circle known as the ecliptic. The three last celestial spheres include Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Beyond these planets shines the heaven of the fixed stars. It rotates upon itself from east to west, with an inconceivable rapidity and an incalculable force of impulsion, for it is this which sets in motion all the fabulous machine. Ptolemaus places on the extreme confines of his vast Whole the eternal abode of the blessed. Thrice happy they in having no further cause to concern themselves %I c r ~NT about so terrible a system ; a system far from transparent, notwithstand ing all its crystal! S The treatise in which the Greek SU N X astronomer summed up his labours r _N_U remained for generations in high ( favour with the learned, and especi r F; r ally with the Arabs, whose privilegp and renown it is to have preserved intact the precious deposit of the sciences, when the Europe of the N - twelfth and thirteenth centuries was plunged in the night-shadows of the profoundest ignorance. -

KOMUNIKATY Mazurskoawarmińskie

Towarzystwo Naukowe i Ośrodek Badań Naukowych im. Wojciecha Kętrzyńskiego KOMUNIKATY AZURSKO armińskie KwartalnikM nr 4(294)-W Olsztyn 2016 KOMUNIKATY MAZURSKO-WARMIŃSKIE Czasopismo poświęcone przeszłości ziem Polski północno-wschodniej RADA REDAKCYJNA: Stanisław Achremczyk (przewodniczący), Darius Baronas, Janusz Jasiński, Igor Kąkolewski, Olgierd Kiec, Andrzej Kopiczko, Andreas Kossert, Jurij Kostiaszow, Cezary Kuklo, Ruth Leiserowitz, Janusz Małłek, Sylva Pocyté, Tadeusz Stegner, Mathias Wagner, Edmund Wojnowski REDAGUJĄ: Grzegorz Białuński, Grzegorz Jasiński (redaktor), Jerzy Kiełbik, Alina Kuzborska (redakcja językowa: język niemiecki), Bohdan Łukaszewicz, Aleksander Pluskowski (redakcja językowa: język angielski), Jerzy Sikorski, Seweryn Szczepański (sekretarz), Ryszard Tomkiewicz. Instrukcja dla autorów dostępna jest na stronie internetowej pisma Wydano dzięki wsparciu fi nansowemu Marszałka Województwa Warmińsko-Mazurskiego oraz Ministerstwa Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego Articles appearing in Masuro-Warmian Bulletin are abstracted and indexed in BazHum and Historical Abstracts Redakcja KMW informuje, że wersją pierwotną (referencyjną) czasopisma jest wydanie elektroniczne. Adres Redakcji: 10-402 Olsztyn, ul. Partyzantów 87, tel. 0-89 527-66-18, www.obn.olsztyn.pl; [email protected]; Ark. wyd. 12,3; ark. druk. 10,75. Przygotowanie do druku: Wydawnictwo „Littera”, Olsztyn, druk Warmia Print, Olsztyn, ul. Pstrowskiego 35C ISSN 0023-3196 A RTYKułY I MATERIAłY Robert Klimek AccoUNts OF THE Catholic CHUrch adoptiNG sacred paGAN places -

John Worsdale and Thomas Oxley

Placidean teachings in early nineteenth-century Britain: John Worsdale and Thomas Oxley Martin Gansten Abstract John Worsdale (1766 – c. 1826) has been described as something of a historical anomaly, perhaps the last representative of a dying astrological tradition, struggling uselessly against the rising tide of modernity. While this may be true with regard to the natural philosophy underpinning his view of how and why astrology works, Worsdale’s actual practices place him rather in the vanguard of an emerging modern astrology characterized by a modified Placideanism. Although the first stirrings of Placidean teachings were felt in Britain towards the end of the 17th century, they gained firm ground only after the subsequent hiatus of judicial astrology spanning most of the 18th. This paper examines the British adoption and transformation of the doctrines of Placidus, particularly as evinced in the writings of John Worsdale and those of his junior contemporary and occasional critic, Thomas Oxley (1789 – 1851). he history of modern astrology arguably begins in Italy, where, in 1650, the T Olivetan monk and professor of mathematics Placido de Titi (better known as Placidus, 1603 – 1668) published his Physiomathematica sive coelestis philosophia, ‘Physiomathematics or celestial philosophy’.1 According to his perhaps most famous statement, Placidus ‘desired no other guides but Ptolemy and Reason’.2 Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos being a most incomplete guide for a practising astrologer, the proportion of Placidus’ own reason in the resulting system was, for better or worse, correspondingly 1 Also known as Quaestionum physiomathematicarum libri tres, ‘Three books on physiomathematical questions’ and first published under the pseudonym Didacus Prittus Pelusiensis – pace Lynn Thorndike, who, in A history of magic and experimental science, vol. -

Nicolaus Copernicus Immanuel Kant

NICOLAUS COPERNICUS IMMANUEL KANT The book was published as part of the project: “Tourism beyond the boundaries – tourism routes of the cross-border regions of Russia and North-East Poland” in the part of the activity concerning the publishing of the book “On the Trail of Outstanding Historic Personages. Nicolaus Copernicus – Immanuel Kant” 2 Jerzy Sikorski • Janusz Jasiński ON THE TRAIL OF OUTSTANDING HISTORIC PERSONAGES NICOLAUS COPERNICUS IMMANUEL KANT TWO OF THE GREATEST FIGURES OF SCIENCE ON ONCE PRUSSIAN LANDS “ElSet” Publishing Studio, Olsztyn 2020 PREFACE The area of former Prussian lands, covering the southern coastal strip of the Baltic between the lower Vistula and the lower Nemunas is an extremely complicated region full of turmoil and historical twists. The beginning of its history goes back to the times when Prussian tribes belonging to the Balts lived here. Attempts to Christianize and colonize these lands, and finally their conquest by the Teutonic Order are a clear beginning of their historical fate and changing In 1525, when the Great Master relations between the Kingdom of Poland, the State of the Teutonic Order and of the Teutonic Order, Albrecht Lithuania. The influence of the Polish Crown, Royal Prussia and Warmia on the Hohenzollern, paid homage to the one hand, and on the other hand, further state transformations beginning with Polish King, Sigismund I the Old, former Teutonic state became a Polish the Teutonic Order, through Royal Prussia, dependent and independent from fief and was named Ducal Prussia. the Commonwealth, until the times of East Prussia of the mid 20th century – is The borders of the Polish Crown since the times of theTeutonic state were a melting pot of events, wars and social transformations, as well as economic only changed as a result of subsequent and cultural changes, whose continuity was interrupted as a result of decisions partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793, madeafter the end of World War II. -

Historical Astronomy

Historical Astronomy (Neolithic record of Moon Phases) Introduction Arguably the history of astronomy IS the history of science. Many cultures carried out astronomical observations. However, very few formed mathematical or physical models based on their observations. It is those that did that we will focus on here, primarily the Babylonians and Greeks. Other Examples At the same time, that focus should not cause us to forget the impressive accomplishments of other cultures. Other Examples ∼ 2300 year old Chankillo Big Horn Medicine Wheel, Observatory, near Lima, Wyoming Peru Other Examples Chinese Star Map - Chinese records go back over 4000 Stonehenge, England years Babylonian Astronomy The story we will follow in more detail begins with the Babylonians / Mesopotamians / Sumerians, the cultures that inhabited the “fertile crescent.” Babylonian Astronomy Their observations and mathematics was instrumental to the development of Greek astronomy and continues to influence science today. They were the first to provide a mathematical description of astronomical events, recognize that astronomical events were periodic, and to devise a theory of the planets. Babylonian Astronomy Some accomplishments: • The accurate prediction of solar and lunar eclipses. • They developed mathematical models to predict the motions of the planets. • Accurate star charts. • Recognized the changing apparent speed of the Sun’s motion. • Developed models to account for the changing speed of the Sun and Moon. • Gave us the idea of 360◦ in a circle, 600 in a degree, 6000 in a minute. Alas, only very fragmentary records of their work survives. Early Greek The conquests of Alexander the Great are oen credited with bringing knowl- edge of the Babylonians science and mathematics to the Greeks.